Gardens Are a Physical Manifestation of Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year of Le Nôtre

ch VER ât Sail ecouverture conférence de presse version déf.indd 1 aules 18/01/2012 13:01:48 3 CONTENTS Press conference - 26 january 2012 Foreword 4 Versailles on the move 7 The exhibitions in versailles 8 Versailles to arras 12 Events 13 Shows 15 Versailles rediscovered 19 Refurnishing versailles 21 What the rooms were used for 26 Versailles and its research centre 28 Versailles for all 31 2011, Better knowledge of the visitors to versailles 32 A better welcome, more information 34 Winning the loyalty of visitors 40 Versailles under construction 42 The development plan 43 Safeguarding and developing our heritage 48 More on versailles 60 Budget 61 Developing and enhancing the brand 63 Sponsors of versailles 64 Versailles in figures 65 Appendices 67 Background of the palace of versailles 68 Versailles in brief 70 Sponsors of the palace of versailles 72 List of the acquisitions 74 Advice for visitors 78 Contacts 80 4 Foreword This is the first time since I was appointed the effects of the work programme of the first phase President of the Public Establishment of the Palace, of the “Grand Versailles” development plan will be Museum and National Estate of Versailles that I considerable. But the creation of this gallery which have had the pleasure of meeting the press. will present the transformations of the estate since Flanked by the team that marks the continuity Louis XIII built his hunting lodge here marks our and the solidity of this institution, I will review the determination to provide better reception facilities remarkable results of 2011 and, above all, the major for our constantly growing numbers of visitors by projects of the year ahead of us. -

Reconstructing the Industrial Revolution: Analyses, Perceptions and Conceptions of Britain’S Precocious Transition to Europe’S First Industrial Society

Working Paper No. 84/04 Reconstructing the Industrial Revolution: Analyses, Perceptions and Conceptions Of Britain’s Precocious Transition to Europe’s First Industrial Society Giorgio Riello And Patrick K. O’Brien © Giorgio Riello & Patrick K. O’Brien Department of Economic History London School of Economics May 2004 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0) 20 7955 7860 Fax: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 Reconstructing the Industrial Revolution: Analyses, Perceptions and Conceptions of Britain’s Precocious Transition to Europe’s First Industrial Society Giorgio Riello and Patrick K. O’Brien Summary The Industrial Revolution continues to be analysed by economic historians deploying the conceptual vocabularies of modern social science, particularly economics. Their approach which gives priority to the elaboration of causes and processes of evolution is far too often and superficially contrasted with post- modern forms of social and cultural history with their aspirations to recover the meanings of the Revolution for those who lived through its turmoil and for ‘witnesses’ from the mainland who visited the offshore economy between 1815- 48. Our purpose is to demonstrate how three distinct reconstructions of the Revolution are only apparently in conflict and above all that a contextualised analysis of observations of travellers from the mainland and the United States provides several clear insights into Britain’s famous economic transformation. Introduction Eric Hobsbawm observed: ‘words are witnesses which often speak louder than documents’.1 Together with the French Revolution and the Renaissance, the Industrial Revolution belongs to a restricted group of historical conjunctures that are famous. -

Court of Versailles: the Reign of Louis XIV

Court of Versailles: The Reign of Louis XIV BearMUN 2020 Chair: Tarun Sreedhar Crisis Director: Nicole Ru Table of Contents Welcome Letters 2 France before Louis XIV 4 Religious History in France 4 Rise of Calvinism 4 Religious Violence Takes Hold 5 Henry IV and the Edict of Nantes 6 Louis XIII 7 Louis XIII and Huguenot Uprisings 7 Domestic and Foreign Policy before under Louis XIII 9 The Influence of Cardinal Richelieu 9 Early Days of Louis XIV’s Reign (1643-1661) 12 Anne of Austria & Cardinal Jules Mazarin 12 Foreign Policy 12 Internal Unrest 15 Louis XIV Assumes Control 17 Economy 17 Religion 19 Foreign Policy 20 War of Devolution 20 Franco-Dutch War 21 Internal Politics 22 Arts 24 Construction of the Palace of Versailles 24 Current Situation 25 Questions to Consider 26 Character List 31 BearMUN 2020 1 Delegates, My name is Tarun Sreedhar and as your Chair, it's my pleasure to welcome you to the Court of Versailles! Having a great interest in European and political history, I'm eager to observe how the court balances issues regarding the French economy and foreign policy, all the while maintaining a good relationship with the King regardless of in-court politics. About me: I'm double majoring in Computer Science and Business at Cal, with a minor in Public Policy. I've been involved in MUN in both the high school and college circuits for 6 years now. Besides MUN, I'm also involved in tech startup incubation and consulting both on and off-campus. When I'm free, I'm either binging TV (favorite shows are Game of Thrones, House of Cards, and Peaky Blinders) or rooting for the Lakers. -

£75,000 Awarded to Browne's Folly Site

Foll- The e-Bulletin of The Folly Fellowship The Folly Fellowship is a Registered Charity No. 1002646 and a Company Limited by Guarantee No. 2600672 Issue 34: £75,000 awarded to January 2011 Browne’s Folly site Upcoming events: 06 March—Annual General Meeting starting at 2.30pm at athford Hill (Wiltshire) is a leased the manor at Monkton Far- East Haddon Village Hall, B haven for some of our rar- leigh in 1842 and used the folly as Northamptonshire. Details est flora and fauna, including the a project for providing employment were enclosed with the Journal White Heleborine and Twayblade during the agricultural depression. and are available from the F/F website www.follies.org.uk Orchid, and for Greater Horseshoe He also improved the condition of and Bechstein‟s Bats. Part of it is the parish roads and built a school 18-19 March—Welsh Week- owned by the Avon Wildlife Trust in the centre of the village where end with visits to Paxton‟s who received this month a grant of he personally taught the girls. Tower, the Cilwendeg Shell House, and the gardens and £75,000 to spend on infrastructure After his death on 2 August grotto at Dolfor. Details from and community projects such as 1851, the manor was leased to a [email protected] the provision of waymark trails and succession of tenants and eventu- information boards telling visitors ally sold to Sir Charles Hobhouse about the site and about its folly. in 1873: his descendants still own The money was awarded from the estate. -

Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia (This Is an Edited Version of a Previously Published Article by Jadranka Beresford-Peirse)

ancient Pterocarya stenoptera (champion), Thuyopsis dolobrata and Phyllocladus alpinus ‘Silver Blades’. We just had time to admire Michelia doltsopa in flower before having to leave this interesting garden. Our final visit was to Fonmom Castle, the home of Sir Brooke Boothby who had very kindly invited us all to lunch. We sat at a long table in a room orig- inally built in 1180, and remodelled in Georgian times with beautiful plaster- work and furnishings. After lunch we had a tour of the garden which is on shallow limestone soil, and at times windswept. We admired a large Fagus syl- vatica f. purpurea planted on the edge of the escarpment in 1818, that had been given buttress walls to hold the soil and roots. There was a small Sorbus domes- tica growing in the lawn and we learnt that this tree is a native in the country nearby. We walked through the closely planted ornamental walled garden into the large productive walled vegetable garden. This final visit was a splen- did ending to our tour, and having thanked our host for his warm hospitality, we said goodbye to fellow members and departed after a memorable four days, so rich in plant content and well organised by our leader Rose Clay. ARBORETUM NEWS Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia (This is an edited version of a previously published article by Jadranka Beresford-Peirse) Vicinis laudor sed aquis et sospite celo Plus placeo et cultu splendidioris heri Haec tibi sunt hominum vestigia certa viator Ars ubi naturam perficit apta rudem. (Trsteno, 1502) The inscription above, with its reference to “the visual traces of the human race” is carved onto a stone in a pergola at the Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia, a place of beauty arising like a phoenix from the ashes of wanton destruction and natural disasters. -

From Garden to Landscape: Jean-Marie Morel and the Transformation of Garden Design Author(S): Joseph Disponzio Source: AA Files, No

From Garden to Landscape: Jean-Marie Morel and the Transformation of Garden Design Author(s): Joseph Disponzio Source: AA Files, No. 44 (Autumn 2001), pp. 6-20 Published by: Architectural Association School of Architecture Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/29544230 Accessed: 25-08-2014 19:53 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Architectural Association School of Architecture is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to AA Files. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.103.149.52 on Mon, 25 Aug 2014 19:53:16 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions From to Garden Landscape Jean-Marie Morel and the Transformation of Garden Design JosephDisponzio When the French landscape designer Jean-Marie Morel died on claim to the new style. Franc, ois de Paule Latapie, a protege of 7 October, 1810, the Journal de Lyon et du Departement du Rhone Montesquieu, was first to raise the issue in his translation of gave his obituary pride of place on the front page of its Thomas Whately's Observations onModern Gardening (1770), the ii October issue. It began simply: 'Jean-Marie Morel, architecte first theoretical text on picturesque gardening. -

Catalogue-Garden.Pdf

GARDEN TOURS Our Garden Tours are designed by an American garden designer who has been practicing in Italy for almost 15 years. Since these itineraries can be organized either for independent travelers or for groups , and they can also be customized to best meet the client's requirements , prices are on request . Tuscany Garden Tour Day 1 Florence Arrival in Florence airport and private transfer to the 4 star hotel in the historic centre of Florence. Dinner in a renowned restaurant in the historic centre. Day 2 Gardens in Florence In the morning meeting with the guide at the hotel and transfer by bus to our first Garden Villa Medici di Castello .The Castello garden commissioned by Cosimo I de' Medici in 1535, is one of the most magnificent and symbolic of the Medici Villas The garden, with its grottoes, sculptures and water features is meant to be an homage to the good and fair governing of the Medici from the Arno to the Apennines. The many statues, commissioned from famous artists of the time and the numerous citrus trees in pots adorn this garden beautifully. Then we will visit Villa Medici di Petraia. The gardens of Villa Petraia have changed quite significantly since they were commissioned by Ferdinando de' Medici in 1568. The original terraces have remained but many of the beds have been redesigned through the ages creating a more gentle and colorful style. Behind the villa we find the park which is a perfect example of Mittle European landscape design. Time at leisure for lunch, in the afternoon we will visit Giardino di Boboli If one had time to see only one garden in Florence, this should be it. -

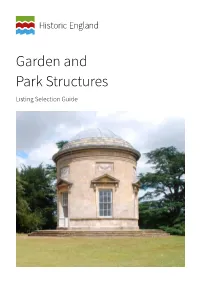

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide looks at buildings and other structures found in gardens, parks and indeed designed landscapes of all types from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. -

Colonial Garden Plants

COLONIAL GARD~J~ PLANTS I Flowers Before 1700 The following plants are listed according to the names most commonly used during the colonial period. The botanical name follows for accurate identification. The common name was listed first because many of the people using these lists will have access to or be familiar with that name rather than the botanical name. The botanical names are according to Bailey’s Hortus Second and The Standard Cyclopedia of Horticulture (3, 4). They are not the botanical names used during the colonial period for many of them have changed drastically. We have been very cautious concerning the interpretation of names to see that accuracy is maintained. By using several references spanning almost two hundred years (1, 3, 32, 35) we were able to interpret accurately the names of certain plants. For example, in the earliest works (32, 35), Lark’s Heel is used for Larkspur, also Delphinium. Then in later works the name Larkspur appears with the former in parenthesis. Similarly, the name "Emanies" appears frequently in the earliest books. Finally, one of them (35) lists the name Anemones as a synonym. Some of the names are amusing: "Issop" for Hyssop, "Pum- pions" for Pumpkins, "Mushmillions" for Muskmellons, "Isquou- terquashes" for Squashes, "Cowslips" for Primroses, "Daffadown dillies" for Daffodils. Other names are confusing. Bachelors Button was the name used for Gomphrena globosa, not for Centaurea cyanis as we use it today. Similarly, in the earliest literature, "Marygold" was used for Calendula. Later we begin to see "Pot Marygold" and "Calen- dula" for Calendula, and "Marygold" is reserved for Marigolds. -

History of the Flower Garden: the Garden Takes Shape by Caroline Burgess, Director

News from Stonecrop GardenFall 2008s History of the Flower Garden: The Garden Takes Shape by Caroline Burgess, Director Stonecrop grew literally and figuratively out of its spec- tacular albeit challenging site atop a rocky and windswept hill, surrounded by close woods and long, pastoral views down the Hudson Valley. Like all cultivated landscapes, Stonecrop, however, is just as much an expression of the ideas and aspirations of the people who create and inhabit it as the native landscape from whence it sprang. Frank Cabot’s three-part series of articles which appeared previ- ously in our newsletter beautifully documents this process of accommodating both man and nature, telling of the early years he and his family spent at Stonecrop. In this new series, I will continue the tale, using the story of our Flower Garden to illustrate the garden-making process at Stonecrop during my tenure. An Englishwoman by birth, I arrived in the United States as the Director of Stonecrop Gardens in 1984 following the completion of my three-year Diploma in Horticulture at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. As Caroline Burgess at Barnsley House a child, I worked in a stable near my family’s home in exchange for the privilege of riding the horses. That stable sequence of surrounding spaces and views. One enters belonged to Rosemary Verey and it wasn’t long before I the house (and now the Flower Garden) through a simple was working as a gardener and later the head gardener yet elegant turf and gravel courtyard ringed in trees. in her acclaimed gardens at Barnsley House. -

The RHS Lindley Library IBRARY L INDLEY RHS, L

Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library IBRARY L INDLEY RHS, L VOLUME NINE DECEMBER 2012 The history of garden history Cover illustration: Engraved illustration of the gardens at Versailles, from Les Jardins: histoire et description by Arthur Mangin (c.1825–1887), published in 1867. Occasional Papers from the RHS Lindley Library Editor: Dr Brent Elliott Production & layout: Richard Sanford Printed copies are distributed to libraries and institutions with an interest in horticulture. Volumes are also available on the RHS website (www. rhs.org.uk/occasionalpapers). Requests for further information may be sent to the Editor at the address (Vincent Square) below, or by email (brentelliottrhs.org.uk). Access and consultation arrangements for works listed in this volume The RHS Lindley Library is the world’s leading horticultural library. The majority of the Library’s holdings are open access. However, our rarer items, including many mentioned throughout this volume, are fragile and cannot take frequent handling. The works listed here should be requested in writing, in advance, to check their availability for consultation. Items may be unavailable for various reasons, so readers should make prior appointments to consult materials from the art, rare books, archive, research and ephemera collections. It is the Library’s policy to provide or create surrogates for consultation wherever possible. We are actively seeking fundraising in support of our ongoing surrogacy, preservation and conservation programmes. For further information, or to request an appointment, please contact: RHS Lindley Library, London RHS Lindley Library, Wisley 80 Vincent Square RHS Garden Wisley London SW1P 2PE Woking GU23 6QB T: 020 7821 3050 T: 01483 212428 E: library.londonrhs.org.uk E : library.wisleyrhs.org.uk Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library Volume 9, December 2012 B. -

The NAT ION AL

The NAT ION A L HORTICUL TURAL MAGAZINE JANUARY -- - 1928 The American Horticultural Society A Union of The National Horticultural Society and The American Horticultural Society, at Washington, D. C. Devoted to the popularizing of all phases of Horticulture: Ornamental Gardening, including Landscape Gardening and Amateur Flower Gar:dening; Professional Flower Gardening or Floriculture; Vegetable Gardening; Fruit Growing and all activities allied with Horticulture. PRESENT ROLL OF OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS March 1, 1927 OFFICERS President, F. L. Mulford, 2552 Tunlaw Road, Washington, D. C. First Vice-President, Mrs. Fannie Mahood Heath, Grand Forks, N. D. Second Vice-President, H. A. Fiebing, Milwaukee, Wis. Secretary, D. Victor Lumsden, 1629 Columbia Road N. W., Washington, D. C. Treasurer, Otto Bauer, 1216 H Street N. W., Washington, D. C. DIRECTORS TERM EXPIRING IN 1928 Mrs. Pearl Frazer, Grand Forks, N. D. David Lumsden, Battery Park, Bethesda, Md. J. Marion Shull, 207 Raymond Street, Chevy Chase, Md. Hamilton Traub, University Farm, St. Paul, Minn. A. L. Truax, Crosby, N. D. TERM EXPIRING IN 1929 G. E. Anderson, Twin Oaks, Woodley Road, Washington, D. C. Mrs. L. H. Fowler, Kenilworth, D. C. V. E. Grotlisch, Woodside Park, Silver Spring, Md. Joseph J. Lane, 19 W. 44th Street, New York City. O. H. Schroeder, Faribault, Minn. Editorial Committee: B. Y. Morrison, Chairman; Sherman R. Duffy, V. E. Grotlisch, P. L. Ricker, J. Marion Shull, John P. Schumacher, Hamilton Traub. Entered as seoond-ola•• matter Maroh 22, 1927, at the Post Offioe a.t Washington, D. C" under the Act of August 24, 1912. 2 THE NATIONAL HORTICULTURAL MAGAZINE Jan.