Regulating Robocalls: Are Automated Calls the Sound Of, Or a Threat To, Democracy Jason C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Accused of Pro-Roe Push Poll

MELVILLE CITY HEo RALD Volume 25 N 19 Melville City’s own INDEPENDENT newspaper li treet, remantle Saturday May 10, 2014 Leeming to Kardinya Edition - etterboed to eeming, ateman, ull ree, ardinya, h a www.fremantleherald.com/melvilles urdoh, urdoh niversity, illagee and inthrop *Fortnightly Email: [email protected] B ell tolls for etla d s by STEVE GRANT • Save Beeliar etlands members are reeling following speculation eeliar etlands says te bbott government is set to the arnett government should fund the construction of Roe 8 stop pushing oe until appeals by making it s first toll road against its environmental Teyre promising mass action to approval have been heard stop te proect Photo by Matthew heir all follows transport Dwyer minister ean alder onfirming he’s negotiating funding with the Find the Fake Ad & WIN a bbott government that would Chance for a Feast for 2 be tied to the highway slugging 42 Mews Rd, truies with ’s first toll road Fremantle (The Sunday Times, May 4, 2014). member andi hinna told the Herald her group was still trying For details, please see Competitions to digest the information, given premier olin arnett had said the Want good pay? Some easy, gentle long-planned etension through the exercise? Deliver the Herald to amsar-listed wetlands wouldn’t local letterboxes! It’s perfect for be built in this term of parliament all ages, from young teens to She says the announcement seniors looking to keep active. If maes a moery of government proesses, with appeals against you’re reliable we may just have the ’s environmental approval a round near you (we deliver of the road still to be heard. -

Telephone Calls and Text Messages in State Senate, District

STATE OF MAINE Commission Meeting 09/30/2020 COMMISSION ON GOVERNMENTAL ETHICS Agenda Item #5 AND ELECTION PRACTICES 135 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 04333-0135 To: Commission From: Michael Dunn, Esq., Political Committee Registrar Date: September 22, 2020 Re: Complaint against Public Opinion Research On September 15, 2020, the Commission received a complaint from the Lincoln County Democratic Committee (the “LCDC”) alleging that unknown persons acting under the name of Public Opinion Research have engaged in a “push poll” to influence the general election for State Senate, District #13. ETH 1-8. Voters have received phone calls from live callers asking questions that are likely designed to influence their vote and text messages linking to an online survey conducted through the SurveyMonkey.com containing similar questions. According to the LCDC, the organizers of the telephone campaign have violated three disclosure requirements in Maine Election Law: • the callers have not provided any “disclaimer statement” identifying who paid for the calls, • the calls do not meet special disclosure requirements applicable to push polls in Maine, and • no independent expenditure report has been filed relating to the calls, text messages, and online survey. The LCDC requests that the Commission initiate an investigation into these activities. The Commission staff has been unable to make contact with Public Opinion Research as part of our preliminary investigation. We cannot find an online presence for a polling or political consulting firm with that name. A “push poll” is a paid influence campaign conducted in the guise of a telephone survey. The telephone calls are designed to “push” the listener away from one candidate and towards another candidate. -

Capital Area Transportation Authority Board of Directors Meeting

CAPITAL AREA TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2018 4:00 P.M. - CATA ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE BUILDING AGENDA I. CALL TO ORDER II. PUBLIC COMMENTS & CORRESPONDENCE TO THE BOARD III. CHAIR'S COMMENTS • Nominating Committee • Strategic Planning Committee • Policy Committee IV. CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER'S REPORT V. ACTION ITEMS - PROPOSED CONSENT AGENDA A. APPROVAL OF MINUTES OF AUGUST 15, 2018, BOARD MEETING B. APPROVAL OF TREASURER'S REPORT FOR AUGUST 2018 1. Interim Income Statement 2. Cash Summary 3. Investments 4. Fifth Third Investment Account Reconciliation e. LEGAL COUNSEL RECOMMENDATION PROPOSED MOTION: That the CATA Board of Directors approve the following law firms to represent CATA during FY 2018-2019: Bleakley, Cypher, Parent, Warren & Quinn, P.e.; George Brookover, P.e.; Dickinson Wright, P.L.L.e.; Murphy & Spagnuolo, P.e.; and Miller Johnson Attorneys. D. CATA BOARD MEETING SCHEDULE FOR FY 2018-2019 PROPOSED MOTION: That the proposed CATA Board Meeting Schedule for FY 2018-2019 be adopted as presented. E. FINANCIAL AUTHORITY RESOLUTION PROPOSED MOTION: That the CATA Board of Directors adopts the Resolution set forth below: Page 1 of 3 RESOLUTION OF BOARD OF DIRECTORS WHEREAS, it is necessary for the Capital Area Transportation Authority, a public transportation authority established under 1963 PA 55 ("CATA"), to utilize banking and investment services for the operation of its business. NOW THEREFORE, be it resolved that: 1. CATA's Chief Executive Officer is hereby authorized to execute agreements with Fifth Third Bank and other financial institutions as the Chief Executive Officer deems necessary to provide banking and investment services for an indefinite period, effective on and after September 19, 2018; 2. -

Ye Olde Publisher Vs. Mark Gerzon - Push Polls! Opinion Questions of the Day

• Letters: • L-Chastain chastizes Bag Ban People! • L-Ruemmler says Water District didn’t answer? • L-Luppens opine Eagle-Vail collapse imminent! • Avon & di Simone’s bag ban destroys freedom! Business Briefs – www.BusinessBriefs.net – Volume 10, Number 9 - July 27 thru Aug 30th, 2017 Distributed free online & to almost 900 locations in Vail, Beaver Creek & Eagle County, Colorado. 970-280-5555 . Injury Attorneys • Auto/Motorcycle • Ski/Snowboard • Dog Bites Rep. Diane Mitsch Bush • Other Injuries Free Consult broke a promise to serve! Percentage Fee Bloch & Chapleau 970.926.1700 Ye Olde Publisher vs. VailJustice.com Edwards/Denver Mark Gerzon - push polls! d, The Bad, The Ugly! The Goo • The Stupid: Most of the Avon Council - potted plants in street! • The Surprising: The amount of locals who don’t use VVMC! • The Defective Thinkers: Our elected Climate Change nutcases! • The Obfuscators: Dems afraid of illegal voting commission! lied to voters about ObamaCare! TraTcraec eT Tyyleer rA Agegnecy ncy • The Liars: Republicans who 97 Main9 7S Mtraeine Stt r•e eSt u! Situeit eW W-110066 ! •Ed wEadrwds,a CrOd s8,1 6C32O 81632 • They Don’t Care - 90% of Americans don’t care about Russia. 9P7h0o-n9e:2 967-04-932760-4 •37 0T !T Eymlaeirl:@ ttAylemrr@@Famamfam.c.coom m “We are proud to serve the Vail Valley providing the community with ““WWee arree prroudoud to servvee tthehe VVailail VValleyalley prroovvidingiding tthehe communittyy • Sad: The loss of Lew Meskiman, Ursula Fricker, Dick Blair! exwwitcitethhll eexxxcellentncellentt servi cseer avvicenicced pandro dpruroductoductcts ttsos mtoe meetet al lall y oyyouruourr ri insnsuurranceranceance needsneeds. -

Actualities and Electronic Press Kits, 40, 85, 122 Advertising, Radio

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84749-0 — New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen Philip N. Howard Index More Information Index actualities and electronic press kits, campaigns: candidate type, 145; 40, 85, 122 grassroots or social movement advertising, radio, television, and type, 144; implanted or Astroturf Web site, 88–94 type, 98, 145, 177; lobby group affinity networks, 85, 139, 144–147, type, 144. See also hypermedia 158 campaigns; issue campaigns; mass AFL-CIO, 6, 138 media campaigns; presidential Agora, GrassrootsActivist.org, 120 campaigns America Coming Together (ACT), 18 CandidateShopper, Voting.com, 113 American Association of Retired capo managers, 148 Persons (AARP), 137, 160 categorization: and identity, 37, 183, American Civil Liberties Union 188; as political negotiation, (ACLU), 137 133–134, 141; managed paradoxes, Amnesty International, 84, 85 86, 154, 157 astroturf or implanted campaign. chat and listservs, 112, 239 See campaigns ChoicePoint Technologies, 15 Astroturf Compiler Software, citizenship: historical context, 185; Astroturf-Lobby.org, 86 privatized, 189–190; shadow, Astroturf-Lobby.org, 83–100, 187–189; thin, 185–187 175–176 coding generals, 148 avatars, 116, 174 Columbia School. See Lazarsfeld, Paul; Merton, Robert Barber, Benjamin, 102, 149 conferences and conventions: Baudrillard, Jean, 67 Democratic and Republican blogging, 16, 121, 239 National Convention, 35, 72, 85, Bourdieu, Pierre, 69, 70, 212 166; and group identity, 34–36, 50 cookie, 239–240 campaign managers. See political C-SPAN, 65 consultants cultural frame, 67, 172, 205. See also campaign spending, 91, 146 media effects 261 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84749-0 — New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen Philip N. -

A Tale of Two Paranoids: a Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán

Secrecy and Society ISSN: 2377-6188 Volume 1 Number 2 Secrecy and Authoritarianism Article 3 February 2018 A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán Andria Timmer Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Joseph Sery Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Sean Thomas Connable Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Jennifer Billinson Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Timmer, Andria; Joseph Sery; Sean Thomas Connable; and Jennifer Billinson. 2018. "A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán." Secrecy and Society 1(2). https://doi.org/10.31979/ 2377-6188.2018.010203 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety/vol1/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Secrecy and Society by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán Abstract Within the last decade, a rising tide of right-wing populism across the globe has inspired a renewed push toward nationalism. -

Approved June 2021 Minutes

CATA Board of Directors Meeting – 07/21/2021 ACTION ITEM V A CAPITAL AREA TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING via ZOOM WEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 2021; 4:00 P.M. PRESENT: Nathan Triplett, Chair John Prush Dusty Fancher, Vice Chair Phil Deschaine Shanna Draheim, Secretary/Treasurer Derek Melot Dion’trae Hayes Doug Lecato Mark Grebner Jack Schmitt Robin Lewis CALL TO ORDER: Nathan Triplett, Chair called meeting to order at 4:10 p.m. ABSENT: Jennie Gies ROLL CALL: All present, Jennie Gies was absent. Chair Triplett instructed all participants on the Zoom meeting format in accordance with the authority of Public Act 254, 2020. CORRESPONDENCE TO THE BOARD AND PUBLIC COMMENTS Correspondence to the Board Chair Triplett stated that there were four (4) emails sent to the Board with one (1) email held back for personnel matters. Public Comments Deb Parrish thanked the Board for letting her speak and inquired about the amount of money being saved with having split shifts for full time employees. She also inquired about the incentive money being spent on new drivers. CHAIR’S COMMENTS: Chair Triplett informed the Board that Governor Whitmer intends to lift COVID-19 restrictions on or before July 1, 2021, therefore; CATA will no longer have the authority to hold virtual meetings. Most likely, the June 2021 Board meeting will be the last meeting held virtually. Doug Lecato inquired about Zoom being allowed at any level. Chair Triplett stated that they are still working on the logistics with staff. He stated that without being under a state of emergency order, there are limited options for individual Board members to meet virtually. -

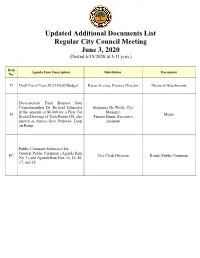

Updated Additional Documents List Regular City Council Meeting June 3, 2020 (Posted 6/15/2020 at 5:11 P.M.)

Updated Additional Documents List Regular City Council Meeting June 3, 2020 (Posted 6/15/2020 at 5:11 p.m.) Item Agenda Item Description Distributor Document No. 17 Draft Fiscal Year 20/21 Draft Budget Karen Aceves, Finance Director Memo w/Attachments Discretionary Fund Request from Councilmember Dr. Richard Schneider Stephanie De Wolfe, City in the amount of $6,000 for a First Cut Manager; 18 Memo Scaled Drawing of State Route 110, also Tamara Binns, Executive known as Arroyo Seco Parkway, Loop Assistant on Ramp Public Comment Submitted for: General Public Comment (Agenda Item PC City Clerk Division E-mail Public Comment No. 3); and Agenda Item Nos. 11, 14, 16, 17, and 18. City of South Pasadena Finance Department Memo Date: June 2, 2020 To: The Honorable City Council Via: Stephanie DeWolfe, City Manager From: Karen Aceves, Finance Director June 3, 2020 City Council Meeting Item No. 17 Additional Document – Draft Fiscal Year 20/21 Draft Budget Re: Attached is an additional document which includes the revenue line items for non-general funds. A.D. 17- 1 Revenue Detail Actual Actual Actual Budget Estimated Proposed Acct Account Title 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2019/20 2020/21 9911-000 Transfers from Other Fund 81,711 - 200,000 95,000 301,163 320,000 Transfers In 81,711 - 200,000 95,000 301,163 320,000 103 - INSURANCE FUND TOTAL 81,711 - 200,000 95,000 301,163 320,000 9911-000 Transfers from Other Fund 3,505,451 - 1,100,000 965,000 965,000 500,000 Transfers In 3,505,451 - 1,100,000 965,000 965,000 500,000 104 - STREET IMPROVEMENTS -

State of Michigan in the Court of Appeals ______

STATE OF MICHIGAN IN THE COURT OF APPEALS __________________________ MARK L. GREBNER, BENTON L. BILLINGS, Court of Appeals No. ________ LOTHAR S. KONIETZKO, AUBREY D. MARRON, JOSEPH S. TUCHINSKY, HUGH C. MCDIARMID, Ingham County Circuit Court BERL N. SCHWARTZ AND PRACTICAL No. 07-1507 POLITICAL CONSULTING, INC., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v STATE OF MICHIGAN, SECRETARY OF STATE, Under MCR 7.205(E)(2) action on TERRI LYNN LAND, this application is required on or before November 16, 2007, as it Defendants-Appellants, concerns the holding of the presidential primaries on January 15, / 2008. DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS' EMERGENCY APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL Michael A. Cox Attorney General Thomas L. Casey (P24215) Solicitor General Counsel of Record Patrick O'Brien (P27306) Heather S. Meingast (P55439) Assistant Attorneys General Attorneys for Defendants Michigan Department of Attorney General 525 W. Ottawa, P.O. Box 30736 Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 373-6434 Date: November 13, 2007 Table of Contents Page Table of Authorities .......................................................................................................................iii Statement of Basis of Jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals.......................................................... vii Statement of Question Involved...................................................................................................viii Statement of Order Appealed from, Allegations of Error and Relief Sought................................. 1 Statement of Facts.......................................................................................................................... -

Communities. More, to Help the Economy We All Share

CATA FISCAL YEAR 2010 ANNUAL REPORT OCTOBER 1, 2009–SEPTEMBER 30, 2010 Moving Certainly individual customers benefit from reliable public transportation People. services, but a strong transit system also helps our entire community thrive in business, education, volunteerism, Moving recreation, and health. CATA connects our communities to all of the above, and Communities. more, to help the economy we all share. With access to affordable and convenient transportation, people are able to lead productive lives that add value to living in our communities. NUMBER CATA RIDERSHIP 1972–2010 FY10 11.35 MILLION RIDES OF RIDES 11 MILLION 10 MILLION 9 MILLION 8 MILLION 7 MILLION 6 MILLION 5 MILLION 4 MILLION 3 MILLION 2 MILLION 1 MILLION 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 1972 1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 1974 Approved by the CATA Board of Directors – March 23, 2011 FY10 CATA LEADERSHIP OCTOBER 1, 2009–SEPTEMBER 30, 2010 2009/2010 2009/2010 2009/2010 CATA BOARD CATA LOCAL ADVISORY OF DIRECTORS EXECUTIVE STAFF COMMITTEE (LAC) Peter A. Kuhnmuench Sandra L. Draggoo Alphonse Swain Board Chair CEO/Executive Director Chairperson City of Lansing Debbie Alexander Capital Area Center for Independent Living Joseph Sambaer Assistant Executive Director Vice-Chair Craig Allen Deb Wiese Lansing Township Director of Maintenance Vice-Chairperson Michigan Rehabilitation Pat Cannon Pat Gilbert Services Secretary-Treasurer Director of Marketing Meridian Township Pat Cannon Janice Kidd LAC Liaison Douglas Lecato Director of Finance CATA Board Member Delhi Township Dwight D. Smith Elma Arnold Robin Lewis Director of Operations Citizen Representative City of Lansing Frank DeRose Ralph Monsma 2009/2010 [began Summer 2010] City of East Lansing AMALGAMATED Tri-County Office on Aging Patricia Munshaw TRANSIT UNION (ATU) #1039 Laura Fortino Meridian Township LANSING, MI Citizen Representative Robert W. -

May 18, 2021 at 6:30 P.M

CHAIRPERSON COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE BRYAN CRENSHAW EMILY STIVERS, CHAIR VICTOR CELENTINO VICE-CHAIRPERSON MARK GREBNER DERRELL SLAUGHTER RYAN SEBOLT DERRELL SLAUGHTER VICE-CHAIRPERSON PRO-TEM ROBERT PEÑA RANDY MAIVILLE ROBIN NAEYAERT INGHAM COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS P.O. Box 319, Mason, Michigan 48854 Telephone (517) 676-7200 Fax (517) 676-7264 THE COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE WILL MEET ON TUESDAY, MAY 18, 2021 AT 6:30 P.M. THE MEETING WILL BE HELD VIRTUALLY AT https://ingham.zoom.us/j/85790207228. Agenda Call to Order Approval of the May 4, 2021 Minutes Additions to the Agenda Limited Public Comment 1. Facilities Department a. Resolution to Authorize a Purchase Order to John E Green for the Print Shop Humidification System Replacement at the Hilliard Building b. Resolution to Authorize an Agreement with Roof Connect to Replace the Roof over the State of Michigan’s Storage Area and Facilities Grounds Garage at the Human Services Building 2. Road Department – Resolution to Authorize an Agreement with Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes & Energy (EGLE) for a 2021 Scrap Tire Market Development Grant 3. Animal Control & Shelter – Resolution to Convert the Part-Time Animal Behaviorist/Enrichment Coordinator Position to Full-Time and Accept a Grant in the Amount of $17,500 from Petco Love for the Ingham County Animal Control and Shelter 4. Human Resources – Resolution to Authorize NEOGOV to Act as an E-Verify Agent 5. Board of Commissioners – Resolution to Authorize the Continuation of the Declaration of the State of Emergency -

Ingham County Board of Commissioners the County

CHAIRPERSON COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE BRYAN CRENSHAW RYAN SEBOLT, CHAIR VICTOR CELENTINO VICE-CHAIRPERSON MARK GREBNER CAROL KOENIG CAROL KOENIG EMILY STIVERS VICE-CHAIRPERSON PRO-TEM RANDY MAIVILLE ROBIN NAEYAERT ROBIN NAEYAERT INGHAM COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS P.O. Box 319, Mason, Michigan 48854 Telephone (517) 676-7200 Fax (517) 676-7264 THE COUNTY SERVICES COMMITTEE WILL MEET ON TUESDAY, MARCH 3, 2020 AT 6:30 P.M., IN CONFERENCE ROOM D & E, HUMAN SERVICES BUILDING, 5303 S. CEDAR, LANSING. Agenda Call to Order Approval of the February 18, 2020 Minutes Additions to the Agenda Limited Public Comment 1. Women’s Commission – Interviews 2. Farmland and Open Space Preservation Board a. Resolution to Approve the Ranking of the 2019 Farmland and Open Space Preservation Programs Application Cycle Ranking and Recommendation to Purchase Permanent Conservation Easement Deeds on the Top Ranked Properties b. Resolution to Approve Proceeding to Close Permanent Conservation Easement Deeds on Vandermeer, Rogers, Launstein and Arend Trust c. Resolution to Authorize a Contract with Cinnaire Title Services d. Resolution Approving the Farmland and Open Space Preservation Board’s Recommended Selection Criteria (Scoring System) for the 2020 Farmland and Open Space Application Cycles and Approve the FOSP Board to Host a 2020 Application Cycle 3. Equalization Department a. Resolution to Approve a Revised Ingham County Remonumentation Plan for Submission to the State of Michigan Office of Land Survey and Remonumentation b. Request for FMLA Extension 4. Facilities Department a. Resolution to Authorize a Two Year Contract Extension with Capitol Walk Parking LLC. for the Parking Spaces Located at Lenawee and Chestnut in Lansing b.