Mitchell's Musings: 3Rd Quarter 2014 from Employmentpolicy.Org

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Accused of Pro-Roe Push Poll

MELVILLE CITY HEo RALD Volume 25 N 19 Melville City’s own INDEPENDENT newspaper li treet, remantle Saturday May 10, 2014 Leeming to Kardinya Edition - etterboed to eeming, ateman, ull ree, ardinya, h a www.fremantleherald.com/melvilles urdoh, urdoh niversity, illagee and inthrop *Fortnightly Email: [email protected] B ell tolls for etla d s by STEVE GRANT • Save Beeliar etlands members are reeling following speculation eeliar etlands says te bbott government is set to the arnett government should fund the construction of Roe 8 stop pushing oe until appeals by making it s first toll road against its environmental Teyre promising mass action to approval have been heard stop te proect Photo by Matthew heir all follows transport Dwyer minister ean alder onfirming he’s negotiating funding with the Find the Fake Ad & WIN a bbott government that would Chance for a Feast for 2 be tied to the highway slugging 42 Mews Rd, truies with ’s first toll road Fremantle (The Sunday Times, May 4, 2014). member andi hinna told the Herald her group was still trying For details, please see Competitions to digest the information, given premier olin arnett had said the Want good pay? Some easy, gentle long-planned etension through the exercise? Deliver the Herald to amsar-listed wetlands wouldn’t local letterboxes! It’s perfect for be built in this term of parliament all ages, from young teens to She says the announcement seniors looking to keep active. If maes a moery of government proesses, with appeals against you’re reliable we may just have the ’s environmental approval a round near you (we deliver of the road still to be heard. -

Telephone Calls and Text Messages in State Senate, District

STATE OF MAINE Commission Meeting 09/30/2020 COMMISSION ON GOVERNMENTAL ETHICS Agenda Item #5 AND ELECTION PRACTICES 135 STATE HOUSE STATION AUGUSTA, MAINE 04333-0135 To: Commission From: Michael Dunn, Esq., Political Committee Registrar Date: September 22, 2020 Re: Complaint against Public Opinion Research On September 15, 2020, the Commission received a complaint from the Lincoln County Democratic Committee (the “LCDC”) alleging that unknown persons acting under the name of Public Opinion Research have engaged in a “push poll” to influence the general election for State Senate, District #13. ETH 1-8. Voters have received phone calls from live callers asking questions that are likely designed to influence their vote and text messages linking to an online survey conducted through the SurveyMonkey.com containing similar questions. According to the LCDC, the organizers of the telephone campaign have violated three disclosure requirements in Maine Election Law: • the callers have not provided any “disclaimer statement” identifying who paid for the calls, • the calls do not meet special disclosure requirements applicable to push polls in Maine, and • no independent expenditure report has been filed relating to the calls, text messages, and online survey. The LCDC requests that the Commission initiate an investigation into these activities. The Commission staff has been unable to make contact with Public Opinion Research as part of our preliminary investigation. We cannot find an online presence for a polling or political consulting firm with that name. A “push poll” is a paid influence campaign conducted in the guise of a telephone survey. The telephone calls are designed to “push” the listener away from one candidate and towards another candidate. -

Ye Olde Publisher Vs. Mark Gerzon - Push Polls! Opinion Questions of the Day

• Letters: • L-Chastain chastizes Bag Ban People! • L-Ruemmler says Water District didn’t answer? • L-Luppens opine Eagle-Vail collapse imminent! • Avon & di Simone’s bag ban destroys freedom! Business Briefs – www.BusinessBriefs.net – Volume 10, Number 9 - July 27 thru Aug 30th, 2017 Distributed free online & to almost 900 locations in Vail, Beaver Creek & Eagle County, Colorado. 970-280-5555 . Injury Attorneys • Auto/Motorcycle • Ski/Snowboard • Dog Bites Rep. Diane Mitsch Bush • Other Injuries Free Consult broke a promise to serve! Percentage Fee Bloch & Chapleau 970.926.1700 Ye Olde Publisher vs. VailJustice.com Edwards/Denver Mark Gerzon - push polls! d, The Bad, The Ugly! The Goo • The Stupid: Most of the Avon Council - potted plants in street! • The Surprising: The amount of locals who don’t use VVMC! • The Defective Thinkers: Our elected Climate Change nutcases! • The Obfuscators: Dems afraid of illegal voting commission! lied to voters about ObamaCare! TraTcraec eT Tyyleer rA Agegnecy ncy • The Liars: Republicans who 97 Main9 7S Mtraeine Stt r•e eSt u! Situeit eW W-110066 ! •Ed wEadrwds,a CrOd s8,1 6C32O 81632 • They Don’t Care - 90% of Americans don’t care about Russia. 9P7h0o-n9e:2 967-04-932760-4 •37 0T !T Eymlaeirl:@ ttAylemrr@@Famamfam.c.coom m “We are proud to serve the Vail Valley providing the community with ““WWee arree prroudoud to servvee tthehe VVailail VValleyalley prroovvidingiding tthehe communittyy • Sad: The loss of Lew Meskiman, Ursula Fricker, Dick Blair! exwwitcitethhll eexxxcellentncellentt servi cseer avvicenicced pandro dpruroductoductcts ttsos mtoe meetet al lall y oyyouruourr ri insnsuurranceranceance needsneeds. -

By JEFF GOODELL Illustration by MATT MAHURIN

The Pentagon & Climate Change The leaders of our armed forces know what’s coming next: melting ice caps, rising sea levels, and mass migrations that will take a toll on much of our military infrastructure and create countless new threats. But climate deniers in Congress are ignoring the warnings and putting our national security at risk By JEFF GOODELL Illustration by MATT MAHURIN 48 | Rolling Stone | RollingStone.com The Pentagon aval station norfolk is the seven feet of sea-level rise by 2100. In 25 headquarters of the U.S. Navy’s Atlan- years, operations at most of these bases are likely to be severely compromised. With- tic fleet, an awesome collection of mil- in 50 years, most of them could be goners. itary power that is in a terrible way the If the region gets slammed by a big hurri- crowning glory of American civiliza- cane, the reckoning could come even soon- tion. Seventy-five thousand sailors and er. “You could move some of the ships to other bases or build new, smaller bases in civilians work here, their job the daily more protected places,” says retired Navy business of keeping an armada spit- Capt. Joe Bouchard, a former command- shined and ready for deployment at any er of Naval Station Norfolk. “But the costs would be enormous. We’re talking hun- moment. When I visited in December, dreds of billions of dollars.” the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roos- Rear Adm. Jonathan White, the Na- evelt was in port, a 1,000-foot-long floating war machine that was central to U.S. -

Actualities and Electronic Press Kits, 40, 85, 122 Advertising, Radio

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84749-0 — New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen Philip N. Howard Index More Information Index actualities and electronic press kits, campaigns: candidate type, 145; 40, 85, 122 grassroots or social movement advertising, radio, television, and type, 144; implanted or Astroturf Web site, 88–94 type, 98, 145, 177; lobby group affinity networks, 85, 139, 144–147, type, 144. See also hypermedia 158 campaigns; issue campaigns; mass AFL-CIO, 6, 138 media campaigns; presidential Agora, GrassrootsActivist.org, 120 campaigns America Coming Together (ACT), 18 CandidateShopper, Voting.com, 113 American Association of Retired capo managers, 148 Persons (AARP), 137, 160 categorization: and identity, 37, 183, American Civil Liberties Union 188; as political negotiation, (ACLU), 137 133–134, 141; managed paradoxes, Amnesty International, 84, 85 86, 154, 157 astroturf or implanted campaign. chat and listservs, 112, 239 See campaigns ChoicePoint Technologies, 15 Astroturf Compiler Software, citizenship: historical context, 185; Astroturf-Lobby.org, 86 privatized, 189–190; shadow, Astroturf-Lobby.org, 83–100, 187–189; thin, 185–187 175–176 coding generals, 148 avatars, 116, 174 Columbia School. See Lazarsfeld, Paul; Merton, Robert Barber, Benjamin, 102, 149 conferences and conventions: Baudrillard, Jean, 67 Democratic and Republican blogging, 16, 121, 239 National Convention, 35, 72, 85, Bourdieu, Pierre, 69, 70, 212 166; and group identity, 34–36, 50 cookie, 239–240 campaign managers. See political C-SPAN, 65 consultants cultural frame, 67, 172, 205. See also campaign spending, 91, 146 media effects 261 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84749-0 — New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen Philip N. -

A Tale of Two Paranoids: a Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán

Secrecy and Society ISSN: 2377-6188 Volume 1 Number 2 Secrecy and Authoritarianism Article 3 February 2018 A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán Andria Timmer Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Joseph Sery Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Sean Thomas Connable Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Jennifer Billinson Christopher Newport University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Timmer, Andria; Joseph Sery; Sean Thomas Connable; and Jennifer Billinson. 2018. "A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán." Secrecy and Society 1(2). https://doi.org/10.31979/ 2377-6188.2018.010203 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/secrecyandsociety/vol1/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Secrecy and Society by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. A Tale of Two Paranoids: A Critical Analysis of the Use of the Paranoid Style and Public Secrecy by Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán Abstract Within the last decade, a rising tide of right-wing populism across the globe has inspired a renewed push toward nationalism. -

California Initiative Review (CIR)

California Initiative Review (CIR) Volume 2014 Article 3 1-1-2014 Cover University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/california-initiative- review Part of the Legislation Commons Recommended Citation University of the Pacific, cM George School of Law (2014) "Cover," California Initiative Review (CIR): Vol. 2014 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/california-initiative-review/vol2014/iss1/3 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Law Reviews at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in California Initiative Review (CIR) by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Introduction The California Initiative Review (CIR) is a non-partisan, objective publication of independent analyses of California statewide ballot initiatives. The CIR is a publication of the Pacific McGeorge Capital Center for Public Law and Policy and is prepared before every statewide election. Each CIR covers all measures qualified for the next statewide ballot, and also contains reports on topics related to initiatives, elections, or campaigns. This edition covers the six statewide ballot measures that will appear on the November 4, 2014 ballot, as well as presents reports on Proposition 49, which was removed from the ballot, Measure L, a history of Three Strikes and the initiative process, and comparative initiative law. The CIR is written and edited by law students enrolled in the California Initiative Seminar course at University of the Pacific, McGeorge School of Law. This fall, 20 students were enrolled in the seminar. -

Legislative Committee Packet

AGENDA BOARD LEGISLATIVE COMMITTEE Friday, August 15, 2014 12:45 p.m., Peralta Oaks Board Room The following agenda items are listed for Committee consideration. In accordance with the Board Operating Guidelines, no official action of the Board will be taken at this meeting; rather, the Committee’s purpose shall be to review the listed items and to consider developing recommendations to the Board of Directors. AGENDA STATUS TIME ITEM STAFF 12:45 p.m. 1. STATE LEGISLATION / ISSUES (R) A. NEW LEGISLATION Doyle/Pfuehler Plan Amendment 1. SB 633 (Pavley D-Agoura Hills) – State Parks Energy Costs Report 2. AB 1922 (Gomez D-Los Angeles) – Greenway Development and Sustainment Act. (I) B. ISSUES Doyle/Pfuehler 1. Water and park bond updates 2. Bike bill update 3. Other issues Doyle/Pfuehler (R) II. FEDERAL LEGISLATION / ISSUES A. NEW LEGISLATION 1. H.R. 5220 (Graves R-MO) No More Land Act – prohibits LWCF dollars from being used for acquisition (I) B. ISSUES Doyle/Pfuehler 1. Land and Water Conservation Fund update 2. Other issues III. ALAMEDA COUNTY TRANSPORTATION SALES TAX (R) Doyle/Pfuehler MEASURE IV. PUBLIC COMMENTS V. ARTICLES (R) Recommendation for Future Board Consideration (I) Information Future 2014 Meetings: (D) Discussion September 19, 2014 November 21, 2014 Legislative Committee Members: October 24, 2014 December 19, 2014 Doug Siden, Chair, Ted Radke, John Sutter, Whitney Dotson, Alternate Erich Pfuehler, Staff Coordinator DRAFT Distribution/Agenda Only Distribution/Agenda Only Distribution/Full Packet Distribution/Full Packet Distribution/Full Packet District: Public: District: Public: AGMs Judi Bank Director Whitney Dotson Carol Johnson Ann Grodin Yolande Barial Bruce Beyaert Director Beverly Lane Jon King Nancy Kaiser Afton Crooks Director Ted Radke Glenn Kirby Ted Radosevich Robert Follrath, Sr. -

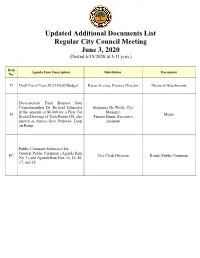

Updated Additional Documents List Regular City Council Meeting June 3, 2020 (Posted 6/15/2020 at 5:11 P.M.)

Updated Additional Documents List Regular City Council Meeting June 3, 2020 (Posted 6/15/2020 at 5:11 p.m.) Item Agenda Item Description Distributor Document No. 17 Draft Fiscal Year 20/21 Draft Budget Karen Aceves, Finance Director Memo w/Attachments Discretionary Fund Request from Councilmember Dr. Richard Schneider Stephanie De Wolfe, City in the amount of $6,000 for a First Cut Manager; 18 Memo Scaled Drawing of State Route 110, also Tamara Binns, Executive known as Arroyo Seco Parkway, Loop Assistant on Ramp Public Comment Submitted for: General Public Comment (Agenda Item PC City Clerk Division E-mail Public Comment No. 3); and Agenda Item Nos. 11, 14, 16, 17, and 18. City of South Pasadena Finance Department Memo Date: June 2, 2020 To: The Honorable City Council Via: Stephanie DeWolfe, City Manager From: Karen Aceves, Finance Director June 3, 2020 City Council Meeting Item No. 17 Additional Document – Draft Fiscal Year 20/21 Draft Budget Re: Attached is an additional document which includes the revenue line items for non-general funds. A.D. 17- 1 Revenue Detail Actual Actual Actual Budget Estimated Proposed Acct Account Title 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 2019/20 2019/20 2020/21 9911-000 Transfers from Other Fund 81,711 - 200,000 95,000 301,163 320,000 Transfers In 81,711 - 200,000 95,000 301,163 320,000 103 - INSURANCE FUND TOTAL 81,711 - 200,000 95,000 301,163 320,000 9911-000 Transfers from Other Fund 3,505,451 - 1,100,000 965,000 965,000 500,000 Transfers In 3,505,451 - 1,100,000 965,000 965,000 500,000 104 - STREET IMPROVEMENTS -

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Enacting the California State Budget for 2015-2016: The Governor Asks the Stockdale Question Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0283s54r Author Mitchell, DJ Publication Date 2021-06-28 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CHI\PTER 6i Enacting the California State Budget for 2015-2016: Ttre Governor Asks the Stockda le Question / \ ntb L\ t/ \' 0\ n U Danriel J.B. Mitchell Professor-Emeritus, UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs ano UCLA Anderson School of Management, daniel,i.b,rnitchell@anderson,ucla,edu This article is based on information onlv l.hrough mid-August and does not reflect subsequent developments Who am l? Whv om I here? Admiral James Stockdale Ross Perot's Third Partv Vice Presidential Candidate at a 1-992 television debater Jerry Brown is the only governor to be elected to frour terms, albeit in two iterations.' Unless term limits are Iifted, no subsequent governor will match his record, But even il he had a ntore conventional gubernatorial history, i.e., if he hadn't been governor in the mid-to-late l-970s and early 1-980s, Lry 2015, he would have "owned" the condition of the state budget. After all, his second iteration began with his (rer)election as governor in 201-0. When he took off ice in January 2011-, and for six months into that terrn, he was under the budget of his predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, But by the time the 201-5-16 state: budget was being proposed and enacted, there had already been three purely Brown state budgets during his second iteration, The budget of 2O1,5-L6, whose enactment we review below, was Brown's fourth. -

Planners Discuss Future Fresno County Rail Hub Written by Jonathan Partridge Patterson Irrigator, Wednesday, Oct

Planners discuss future Fresno County rail hub Written by Jonathan Partridge Patterson Irrigator, Wednesday, Oct. 10, 2007 Rail Dreams: Developers are negotiating with Stanislaus County to develop 4,800 acres in and around the former Crows Landing U.S. Navy airfield into a short -haul rail hub. Above, a train rolls into Crows Landing earlier this year. Developers of a potential industrial park and inland port in Crows Landing are talking with ag exporters about an additional short-haul rail hub in Fresno County. PCCP West Park transportation consultant D.J. Smith estimated the entire project could cost $80 million to $100 million, but it’s too early to know for sure, he said. It’s unclear who would develop the facility, but agricultural exporters and members of West Park’s team are discussing it with regional planning agencies. Advocates for the Fresno County “transloader system” say the project could provide a great service for southern San Joaquin Valley agricultural exporters. “We’re having our civil engineers look at it,” Smith said Friday. PCCP West Park is also negotiating with Stanislaus County to develop 4,800 acres in and around Crows Landing’s former 1,527-acre U.S. Navy airfield, now owned by the county. A key component of West Park’s proposal is an inland port where trains would pick up and drop off containers from the Port of Oakland. West Park developer Gerry Kamilos said the Crows Landing facility remains his top priority and that the Fresno County proposal is not a West Park project. Smith said the idea for a Fresno County port came after West Park officials met with southern San Joaquin Valley agricultural industry representatives in July. -

Reporter Behind Michigan's 1994 Prohibition

About Kevin Dayton Research Publications by Kevin Dayton California Government Project Labor Agreement List California Local Government Logbook Reporter Behind Michigan’s 1994 Prohibition of Capital Appreciation Tweets by @DaytonPubPolicy Bonds (CABs) Watches and Writes about Kevin Dayton the CAB Frenzy at California School @DaytonPubPolicy “…agreed to comply with the State’s Districts Prevailing Wage law, which, it said, added May 14, 2012 / Kevin Dayton / 2 comments $8.9 million to construction costs” pasadenanow.com/main/kimpton-h… Here is a follow-up to my May 11 post entitled Please Read This, Even If You Think Municipal Bonds Are Really BORING: We’re Setting Up the Next Generation of 4h Californians to Pay Staggering Property Taxes. Kevin Dayton A speaker at the California League of Bond Oversight Committees annual conference on @DaytonPubPolicy May 11 mentioned that the State of Michigan banned Capital Appreciation Bonds (CABs) Union Project Labor Agreement mandate on in the 1990s after a reporter for the Detroit Free Press named Joel Thurtell exposed the agenda for Palomar Community College extent of the scheme to the public in his April 5, 1993 investigative article board meeting tonight (May 23, 2017) palomar.edu/gb/2017/2017-0… “Michigan Schools Load the Future With Debt.” It turns out Mr. Thurtell has a personal blog called Joel on the Road, in which he has been tracking and opining on the excessive use of CABs in California, including the mind-boggling one at the Poway Unified School District in San Diego County. He has 4h posted four articles about CAB abuses at California school districts in the past five days.