An Examination of the Ecclesiology Implicit in the Validity of Orders Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte

Preamble. His Excellency. Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa was consecrated as the Roman Catholic Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu in Brazil on December !" #$%&" until certain views he expressed about the treatment of the Brazil’s poor, by both the civil (overnment and the Roman Catholic Church in Brazil caused his removal from the Diocese of Botucatu. His Excellency was subsequently named as punishment as *itular bishop of Maurensi by the late Pope Pius +, of the Roman Catholic Church in #$-.. His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord Carlos Duarte Costa had been a strong advocate in the #$-0s for the reform of the Roman Catholic Church" he challenged many of the 1ey issues such as • Divorce" • challenged mandatory celibacy for the clergy, and publicly stated his contempt re(arding. 2*his is not a theological point" but a disciplinary one 3 Even at this moment in time in an interview with 4ermany's Die 6eit magazine the current Bishop of Rome" Pope Francis is considering allowing married priests as was in the old time including lets not forget married bishops and we could quote many Bishops" Cardinals and Popes over the centurys prior to 8atican ,, who was married. • abuses of papal power, including the concept of Papal ,nfallibility, which the bishop considered a mis(uided and false dogma. His Excellency President 4et9lio Dornelles 8argas as1ed the Holy :ee of Rome for the removal of His Excellency Most Reverend Dom. Carlos Duarte Costa from the Diocese of Botucatu. *he 8atican could not do this directly. 1 | P a g e *herefore the Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil entered into an agreement with the :ecretary of the Diocese of Botucatu to obtain the resi(nation of His Excellency, Most Reverend /ord. -

Theological Studies

VOLUME I · NUMBER 3 SEPTEMBER 1940 Theological Studies CHURCH UNITY AND PROTESTANT MISSIONS EDWARD L. MURPHY, SJ. WESTON COLLEGE Weston, Mass. FFORTS towards unity among certain Protestant groups E have been considered newsworthy of late by the secular press. One has in mind the projected unity among Presby terians and the Protestant Episcopal Church of America and the apparently accomplished unity among the divisions of Methodists last year. Many reasons may be assigned for these attempts and successes, but it would be impossible to under stand adequately this movement among the denominations without some idea of the missionary development of these groups. The rapid geographical extension of denominational* ism, almost exclusively the work of a century and a quarter, with its consequent enormous expenditures of money and per sonnel has had two effects upon denominationalism. In the first place, it has impressed upon the groups the necessity for unity in view of the weakness of division, and secondly it has at the same time complicated the attainment of the unity. Confronted with the millions of pagans in a country such as China or India, the denomination eventually realized the futility and practical impossibility of cutting into such a large mass of error and ignorance by its own individual efforts. The 210 THEOLOGICAL STUDIES denomination necessarily looked about for kinship with other forms of Christianity for the sake not merely of numerical advance but even of survival in the face of such overwhelming odds. It soon became painfully obvious, after the first rush of zeal, that such a mass could not be Christianized by the Lutherans alone, nor the Baptists alone, especially when the de nomination had to face the opposition both of paganism and of divergent groups of Christianity. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

See of Dorchester Papers

From the Bishop of Oxford As a Diocese, we are prayerfully seeking the person whom God is calling to be the next Bishop of Dorchester, one of three Area bishops in the Diocese of Oxford. At the heart of our vision we discern a call to become a more Christ-like Church for the sake of God’s world: contemplative, compassionate and courageous. Most of all we are seeking a new Bishop for Dorchester who will seek to model those qualities and inspire the Church of England across the Dorchester Area to live them out in our daily lives. Our new Bishop will therefore be a person of prayer, immersed in the Scriptures and the Christian tradition, able to be at home with and to love the clergy, parishes and benefices in many different church traditions and many different social contexts. We are seeking a person able to watch over themselves in a demanding role and to model healthy and life-giving patterns of ministry. We want our new bishop to be an inspiring leader of worship, preacher and teacher in a range of different contexts and to be a pastor to the ministers of the Area. The Bishop of Dorchester leads a strong and able Area Team in taking forward the common vision of the Diocese of Oxford in the Dorchester Area. Full details of that process can be found in these pages and on our diocesan website. We are therefore seeking a Bishop who can demonstrate commitment and experience to our diocesan priorities. The Bishop of Dorchester holds a significant place in the civic life of the area: we are therefore seeking a bishop who is able to make a confident contribution to wider society beyond the life of the church in civil, ecumenical and interfaith engagement and who is able to live and articulate the Christian gospel in the public square. -

This Chapter Will Demonstrate How Anglo-Catholicism Sought to Deploy

Building community: Anglo-Catholicism and social action Jeremy Morris Some years ago the Guardian reporter Stuart Jeffries spent a day with a Salvation Army couple on the Meadows estate in Nottingham. When he asked them why they had gone there, he got what to him was obviously a baffling reply: “It's called incarnational living. It's from John chapter 1. You know that bit about 'Jesus came among us.' It's all about living in the community rather than descending on it to preach.”1 It is telling that the phrase ‘incarnational living’ had to be explained, but there is all the same something a little disconcerting in hearing from the mouth of a Salvation Army officer an argument that you would normally expect to hear from the Catholic wing of Anglicanism. William Booth would surely have been a little disconcerted by that rider ‘rather than descending on it to preach’, because the early history and missiology of the Salvation Army, in its marching into working class areas and its street preaching, was precisely about cultural invasion, expressed in language of challenge, purification, conversion, and ‘saving souls’, and not characteristically in the language of incarnationalism. Yet it goes to show that the Army has not been immune to the broader history of Christian theology in this country, and that it too has been influenced by that current of ideas which first emerged clearly in the middle of the nineteenth century, and which has come to be called the Anglican tradition of social witness. My aim in this essay is to say something of the origins of this movement, and of its continuing relevance today, by offering a historical re-description of its origins, 1 attending particularly to some of its earliest and most influential advocates, including the theologians F.D. -

A CONFESSION of FAITH Against Ecumenism

A CONFESSION OF FAITH Against Ecumenism From a Convention of Orthodox Clergymen and Monks Greece, April 2009 Those of us who by the Grace of God have been raised with the dogmas of piety and who follow in everything the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church, believe that: The sole path to salvation of mankind1 is the faith in the Holy Trinity, the work and the teaching of our Lord Jesus Christ, and their continuance within His Body, the Holy Church. Christ is the only true Light;2 there are no other lights to illuminate us, nor any other names that can save us: “Neither is there salvation in any other: for there is none other name under heaven given among men, whereby we must be saved.”3 All other beliefs, all religions that ignore and do not confess Christ “having come in the flesh,”4 are human creations and works of the evil one,5 which do not lead to the true knowledge of God and rebirth through divine Baptism, but instead, mislead men and lead them to perdition. As Christians who believe in the Holy Trinity, we do not have the same God as any of the religions, nor with the so-called monotheistic religions, Judaism and Mohammedanism, which do not believe in the Holy Trinity. For two thousand years, the one Church which Christ founded and the Holy Spirit has guided has remained stable and unshakeable in the salvific Truth that was taught by Christ, delivered by the Holy Apostles and preserved by the Holy Fathers. She did not buckle under the cruel persecutions by the Judeans initially or by idolaters later, during the first three centuries. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR th WEDNESDAY,THE 27 NOVEMBER, 2019 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 63 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 64 TO 68 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 69 TO 81 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 82 TO 92 REGISTRAR (APPLT.)/ REGISTRAR (LISTING)/ REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 27.11.2019 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 27.11.2019 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-I) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE C.HARI SHANKAR FRESH MATTERS & APPLICATIONS ______________________________ 1. W.P.(C) 11586/2019 M/S DIAMOND EXPORT (THROUGH PRIYADARSHI MANISH ITS PARTNER- MR. JAYANT GURJAR) Vs. COMMISSIONER OR CUSTOMS (EXPORTS) ICD, TUGHLAKABAD, NEW DELHI AND ORS FOR ADMISSION _______________ 2. W.P.(C) 11652/2018 DELHI SIKH GURDWARA ABINASH K MISHRA & MANAGEMENT & ANR ASSOCIATES,ANURAG Vs. UNION OF INDIA & ORS AHLUWALIA,ANUJ AGGARWAL 3. W.P.(C) 1624/2019 BINTY YADUNANDAN BANSAL,HS Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ORS. PARIHAR,RAMESH BABU,MANISHA SINGH 4. W.P.(C) 2534/2019 ABHIJIT MISHRA PAYAL BAHL,SANJAY DEWAN,AMIT Vs. OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT & BANSAL SESSIONS JUDGE (SOUTH) 5. W.P.(C) 7752/2019 YESHWANTH SHENOY YESHWANTH SHENOY,RAJESH GOGNA CM APPL. 32183/2019 Vs. THE UNION OF INDIA AND CM APPL. 32184/2019 ORS. 6. W.P.(C) 11639/2019 MAHAVEER PRASAD SAINI SANJAY ABBOT CM APPL. 47826/2019 Vs. GOVERNMENT OF DELHI AND CM APPL. 47827/2019 ANR. AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 7. -

St Stephen's House 2 0 2 0 / 2 0

2020 / 2021 ST STEPHEN’S HOUSE NEWS 2 St Stephen’s House News 2020 / 2021 2020 / 2021 St Stephen’s House News 3 2020 / 2021 PRINCIPAL’S ST STEPHEN’S HOUSE CONTENTS NEWS WELCOME elcome to the latest edition of the NEWS WCollege Newsletter, in what has proved to be the most extraordinary year On the cover for us – as for most people – since the In recognition and Second World War. In March we were able thanks to our alumni for their many and to welcome the Chancellor of the University varied contributions of Oxford, Lord Patten of Barnes, to the Archbishop Stephen Cottrell Covid-19’s unsung alumni to society during (p13) heroes (p10) Covid-19. celebrations on Edward King Day, which were particularly important for us this year News ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 as we marked fifty years of our formal The College during Covid-19 ......................................................................................................................... 5 association with the University of Oxford, and A new VP in the House .................................................................................................................................. 8 forty years of our occupation of our current Alumni: celebrating the unsung heroes of Covid-19 ................................................................................... 10 Michael Dixon & Lydia Jones Joachim Delia Hugo Weaver buildings. Little did we know -

Pilgrim October 2015, CSI Church, Toronto

The Official Monthly Newsletter of CSI Church, Toronto Volume 15 Issue 10 October 2015 2015 Motto ‘Fear God, and keep his commandments; for that is the whole duty of everyone.’ 'ൈദവെ ഭയെ aവെn കനകെള പ്രമാണിച്ചുെകാൾക; aതാകു സകല മനുഷയ്ർക്കും േവതു' Ecclesiastes 12:13 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Achen’s message .... ..3 Bible Portions .......... ..5 Seniors Sunday..…….6 Church News . ........ ..7 Celebrations………....8 Choir Sunday ………..9 Articles ….…....…10,12 Missions Sunday .….11 Youth ....................... 14 Editorial ….. Lead Kindly Light ……. We run routine diagnostic tests of our vehicles, gadgets, health, and everything connected with us. We do so in order to make sure that OCTOBER 2015 everything is working as desired, and that it wouldn’t pose an immi- nent breakdown. When we take so much care about it, how much more should we be really concerned about our hearts, the Operating EDITORIAL BOARD Systems? Chief Editor Heart is considered to be the seat of emotions and the best vault to keep every secret. The desire to keep something as secret rarely es- Rev. George Jacob capes the firewall, unless open to Trojans and backdoors. That said, heart can sometimes become a hindrance to our pilgrimage towards the blessed Jerusalem. When the mundane reality can’t ascertain, Editor discern, learn and guide the hearts of people, the absolute omniscient reality can fathom and decipher the intricacies of our hearts. So the Samuel Anselm Samuel psalmist makes a humble prayer in Psalm 139: 23-24 Search me, God, and know my heart; test me and know my anxious Publication Team thoughts.See if there is any offensive way in me, and lead me in the Shini Samuel way everlasting. -

PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1Llving CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I

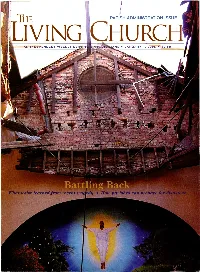

1 , THE PARISH ADMINISTRATION ISSUE 1llVING CHURC----- 1-.··,.:, I, ENDURE ... EXPLORE YOUR BEST ACTIVE LIVING OPTIONS AT WESTMINSTER COMMUNITIES OF FLORIDA! 0 iscover active retirement living at its finest. Cf oMEAND STAY Share a healthy lifestyle with wonderful neighbors on THREE DAYS AND TWO any of our ten distinctive sun-splashed campuses - NIGHTS ON US!* each with a strong faith-based heritage. Experience urban excitement, ATTENTION:Episcopalian ministers, missionaries, waterfront elegance, or wooded Christian educators, their spouses or surviving spouses! serenity at a Westminster You may be eligible for significant entrance fee community - and let us assistance through the Honorable Service Grant impress you with our signature Program of our Westminster Retirement Communities LegendaryService TM. Foundation. Call program coordinator, Donna Smaage, today at (800) 948-1881 for details. *Transportation not included. Westminster Communities of Florida www.WestminsterRetirement.com Comefor the Lifestyle.Stay for a Lifetime.T M 80 West Lucerne Circle • Orlando, FL 32801 • 800.948.1881 The objective of THELIVI N G CHURCH magazine is to build up the body of Christ, by describing how God is moving in his Church ; by reporting news of the Church in an unbiased manner; and by presenting diverse points of view. THIS WEEK Features 16 2005 in Review: The Church Begins to Take New Shape 20 Resilient People Coas1:alChurches in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina BYHEATHER F NEWfON 22 Prepare for the Unexpected Parish sUIVivalcan hinge on proper planning BYHOWARD IDNTERTHUER Opinion 24 Editor's Column Variety and Vitality 25 Editorials The Holy Name 26 Reader's Viewpoint Honor the Body BYJONATHAN B . -

A Long-Simmering Tension Over 'Creeping Infallibility' Published on National Catholic Reporter (

A long-simmering tension over 'creeping infallibility' Published on National Catholic Reporter (http://ncronline.org) A long-simmering tension over 'creeping infallibility' May. 09, 2011 Vatican [1] ordinati.jpg [2] Priests lie prostrate before Pope Benedict XVI during their ordination Mass in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican May 7, 2006. (CNS/Chris Helgren) Rome -- When Pope Benedict XVI used the word "infallible" in reference to the ban on women's ordination in a recent letter informing an Australian bishop he'd been sacked, it marked the latest chapter of a long-simmering debate in Catholicism: Exactly where should the boundaries of infallible teaching be drawn? On one side are critics of "creeping infallibility," meaning a steady expansion of the set of church teachings that lie beyond debate. On the other are those, including Benedict, worried about "theological positivism," meaning that there is such a sharp emphasis on formal declarations of infallibility that all other teachings, no matter how constantly or emphatically they've been defined, seem up for grabs. That tension defines the fault lines in many areas of Catholic life, and it also forms part of the background to the recent Australian drama centering on Bishop William Morris of the Toowoomba diocese. Morris was removed from office May 2, apparently on the basis of a 2006 pastoral letter in which he suggested that, in the face of the priest shortage, the church may have to be open to the ordination of women, among other options. Morris has revealed portions of a letter from Benedict informing him of the action, in which the pope says Pope John Paul II defined the teaching on women priests "irrevocably and infallibly." In comments to the Australian media, Morris said that turn of phrase has him concerned about "creeping infallibility." Speaking on background, a Vatican official said this week that the Vatican never comments on the pope's correspondence but has "no reason to doubt" the authenticity of the letter.