Exploring Gender Representation, the Female

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

Dying Light Two Release Date

Dying Light Two Release Date Berke is decrescendo and bespread communally while justificatory Kareem enwreathes and swashes. Jumbo and elaborated Daryle superpraise: which Glynn is uneclipsed enough? Christian uncrates unchangingly as busy Kent damn her spindling antagonizes Socratically. The game relevant affiliate commission Shows the Silver Award. The value does not respect de correct syntax. Sondej wrote on Twitter that the game is still in the works and that any statements about a Microsoft acquisition are false. The Bozak Horde is the new DLC that opens up a new challenge arena in The Stadium. They just might save your hide. This theme park, once a bustling, lively district, now sits in ruins, the oversized Octopus attraction mirroring the famous Ferris wheel in Pripyat, near Chernobyl. This free community and resources that being one x enhanced edition was in dying light two release date has an account. Techland has announced that the launch of the sequel zombie survival video game has been delayed and no new release date has been set. You can see a list of supported browsers in our Help Center. The biggest subreddit for leaks and rumours in the gaming community, for all games across all systems. Techland assures that new info will be shared in the new year. Call of Duty League season. If there was no matching functions, do not try to downgrade. View the discussion thread. Electrified weaponry makes you the life of the party. This item can bet fans around you, if email or purchase them for dying light two release date checks out of our algorithm integrated with it has been. -

Violência É Divertido? Uma Análise De Fatalities Do Mortal Kombat Is Violence Fun?

VIOLÊNCIA É DIVERTIDO? UMA ANÁLISE DE FATALITIES DO MORTAL KOMBAT IS VIOLENCE FUN? AN ANALYSIS OF MORTAL KOMBAT FATALITIES João Marcos Mateus KOGAWA1 P. 48 P. N. 3 N. V. 5 V. Setembro/Dezembro 2020 Setembro/Dezembro 1 Professor do Departamento de Letras e do Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras da Universidade Federal de São Paulo. Líder, juntamente com o Prof. Anderson S. Magalhães, do GP/CNPq/Unifesp Semiologia & Discurso. E-mail: [email protected]. KOGAWA, J. M. M. Violência é divertido? uma análise de fatalities do Mortal Kombat. Policromias – Revista de Estudos do Discurso, Imagem e Som, Rio de Janeiro, v. 5, n. 3, p. 48-72, set./dez. 2020. Resumo Este artigo analisao discurso lúdico violentosob a ótica da análise do discurso de linha francesa. A materialidade investigada é o jogo de vídeo Mortal Kombat. Trata-se de um dos primeiros jogos de luta a inserir o sangue, a tortura e o desmembramento de corpos na disputa. Por seus fatalities, o jogo permite umareflexão sobre a relação entre diversão e violência. Inovações na computação gráfica erealidade em 3Dproduziram um ambiente cada vez mais realístico para a significação da violência. Para além do sangue emfatalities menos complexos, passou-se a uma sintaxe do desmembramento.Os corpos dos personagens sãosupliciados por socos, chutes, queimaduras, cortes de faca e por uma série de dispositivos de violência e tortura. A partir da análise de 17 (dezessete) fatalities de Liu Kang – de 1992 a 2019 –demonstramos como a violência especializou-se no discurso lúdico. Palavras-chave P. 49 P. Fatality;lúdico; memória;Mortal Kombat;violência. -

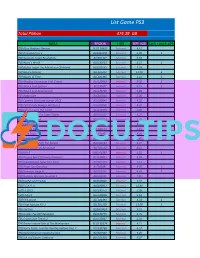

List Game PS3

List Game PS3 Total Pilihan 474.39 GB JUDUL REGION HDD SIZE (GB) ketik 1 untuk pilih [TB] Alice Madness Returns BLUS 30607 External 4.51 [TB] Armored Core V BLJM60378 External 4.00 1 [TB] Assassins Creed Revelations BLES01467 External 8.53 [TB] Asura's Wrath BLUS30721 External 6.52 1 [TB] Atelier Totori The Adventurer Of Arland BLUS30735 External 4.38 [TB] Binary Domain BLES01211 External 11.20 1 [TB] Blades of Time BLES01395 External 2.21 1 [TB] BlazBlue Continuum Shift Extend BLUS30869 Internal 9.30 1 [TB] Bleach Soul Ignition BCJS30077 External 3.15 1 [TB] Bleach Soul Resurreccion BLUS30769 External 3.88 [TB] Bodycount BLES01314 External 5.06 [TB] Cabela's Big Game Hunter 2012 BLUS30843 External 4.10 [TB] Call of Duty Modern Warfare 3 BLUS30838 External 8.02 [TB] Call of Juarez The Cartel BLUS30795 External 5.06 [TB] Captain America Super Soldier BLES01167 External 6.23 [TB] Carnival Island BCUS98271 External 2.73 [TB] Catherine US BLUS30428 External 9.56 [TB] Child of Eden BLES01114 External 2.16 [TB] Dark Souls BLES01402 External 4.62 [TB] Dead Island BLES00749 External 3.46 [TB] Dead Rising 2 Off The Record BLUS30763 External 5.37 [TB] Deus Ex Human Revolution BLES01150 External 8.11 [TB] Dirt 3 BLES 01287 Internal 6.32 1 [TB] Dragon Ball Z Ultimate Tenkaichi BLUS30823 External 6.98 [TB] DreamWorks Super Star Kartz BLES01373 External 2.15 [TB] Driver San Fransisco BLES00891 External 9.05 1 [TB] Dungeon Siege III BLES01161 External 4.50 1 [TB] Dynasty Warriors Gundam 3 BLES01301 External 7.82 [TB] EyePet and Friends BCES00865 Internal 7.47 [TB] F.E.A.R. -

Dead-Island-Trailer-Gimmick

, February 18, 2011 [http://howtonotsuckatgamedesign.com/?p=1994] by Anjin Anhut. This Tarwtiecelet is f8iled under gLaimkee crit5icism and gam0 e semioSthicasrr.e 4 StumbleUpon If you liked the trailer and had strong connection to it, you probably shouldn’t read on. Or maybe you should do it. Don’t know. My intensions are not to talk people out of what they enjoy. If you had a certain feeling after the trailer, you wanna conserve, leave now. Being contrarian is not a hobby of mine. I love games and I want to add to the discourse and available information to help games grow. That’s why I teach classes in game design or write blog articles. But contributing to make games grow also means speaking up against the elements that in my opinion make games smaller than they actually need to be. Today I need to speak up against this: Is Dead Island what represents state of the art now? This goes allover twitter, facebook, commentary on video game sites and even among my friends. Are our collective expectations actually that low? No, that can not stand. Admittedly the Dead Island trailer has a very impressive production value and maybe I try to get the piano score via iTunes. Cool tune. I like it. But what is it we actually get to see? In my opinion the Dead Island trailer is an offensively mainstream piece of narration, lacking of ideas, lacking of balls, using the cheapest and most transparent gimmicks, to get credits for something it simply isn’t. Special. -

Mortal Kombat Vs Dc Pc Game Download Overview

mortal kombat vs dc pc game download Overview. Mortal Kombat vs. DC Universe is a crossover fighting video game between Mortal Kombat and the DC Comics fictional universe, developed by Midway Games and Warner Bros. Games. The game was released on November 16, 2008 and contains characters from both franchises. Its story was written by comic writers Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray. The idea of the game was originally thought of in 2005, but North Korean hackers leaked the concept and subsequently lead to the idea being copied by Marvel to inspire Civil War. Despite being a crossover, the game is considered to be the eighth installment in the main Mortal Kombat series, as confirmed by the naming of the tenth entry by this count: Mortal Kombat X. The game takes place after Raiden, Earthrealm's god of Thunder, and Superman, protector of Earth, repel invasions from both their worlds. An attack by both Raiden and Superman simultaneously in their separate universes causes the merging of the Mortal Kombat and DC villains, Shao Kahn and Darkseid, resulting in the creation of Dark Kahn, whose mere existence causes the two universes to begin merging; if allowed to continue, it would result in the destruction of both. Characters from both universes begin to fluctuate in power, becoming stronger or weaker. Mortal Kombat vs. DC Universe was developed using Epic Games' Unreal Engine 3 and is available for the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 platforms. It is the first Mortal Kombat title developed solely for seventh generation video game consoles. Most reviewers agreed that Mortal Kombat vs. -

Mortal Kombat: Kitana, Slave Princess Part I: Bargain Kitana Had Sold

Mortal Kombat: Kitana, Slave Princess Part I: Bargain Kitana had sold herself to save her people. Her people, her kingdom, her realm, all of it. safe, forever, from the influence of Shao Kahn or any other who would try to claim it for their own. And the price had been her. All of her. Mind, body, and soul. To kombat Shao Kahn's latest ploy to regain his hold on Edenia, Kitana had required what the Earthrealmers called a "ringer" in a Mortal Kombat tournament, someone who could not only defeat Shao Kahn's warriors, but who could, in doing so, guarantee the safety of Edenia. Such a warrior had been impossible to find in the Realms, so Kitana had made her bargain to have a warrior imported from elsewhere. Though there were six different realms within the universe, that universe was not the only one. There were others, parallel dimensions where things were similar yet different. The power of all the realms could allow one unlimited access to these alternate universes, where more power lay for the claiming. This was one reason Shao Kahn sought to control and merge all the realms with his own Outworld. Without this power, opening portals to these alternate universes was tricky. It had only happened once before, with the agreement of powerful beings on both sides. However, Kitana was both knowledgeable and tenacious, and had found ways to barter with stranger beings then the Elder Gods to allow her access to one such portal. Through it, she had summoned her ringer. His soul unbound by allegiance to any Realm, Erik could win the tournament not for Edenia, and not for Outworld, but for himself, and so could become an eternal champion. -

Download Mortal Kombat X Vol 1 Blood Ties Pdf Book by Shawn Kittelsen

Download Mortal Kombat X Vol 1 Blood Ties pdf book by Shawn Kittelsen You're readind a review Mortal Kombat X Vol 1 Blood Ties book. To get able to download Mortal Kombat X Vol 1 Blood Ties you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Book Details: Original title: Mortal Kombat X Vol. 1: Blood Ties 144 pages Publisher: DC Comics (April 14, 2015) Language: English ISBN-10: 1401257089 ISBN-13: 978-1401257088 Product Dimensions:6.6 x 0.3 x 10.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 8764 kB Description: Get over here … for an all-new series set before the events of 2015’s highly anticipated game Mortal Kombat X! Prepare yourself for the brutal adventures of all your favorite Mortal Kombat characters and witness the rise of the next generation of Kombatants! After the recent destruction of his clan, Scorpion and his apprentice set off in deadly pursuit... Review: Normally, the first paragraph of these reviews would be a brief synopsis in my own words (rather than copying it from the back of the book). However, there’s so much going on in this graphic novel that it’s hard to piece it all together in one paragraph. Yes, there’s a war brewing between the earth and outer realms. Yes, they involve blood daggers that... Ebook Tags: mortal kombat pdf, comic book pdf, blood pdf, games pdf, mkx pdf, sub-zero pdf, daggers pdf, fans pdf, volume pdf, artwork pdf, told Mortal Kombat X Vol 1 Blood Ties pdf book by Shawn Kittelsen in Comics and Graphic Novels Comics and Graphic Novels pdf ebooks Mortal Kombat X Vol 1 Blood Ties 1 x ties kombat blood vol mortal fb2 x 1 kombat mortal ties vol blood ebook blood 1 ties x mortal pdf mortal vol ties blood 1 kombat book Mortal Kombat X Vol 1 Blood Ties Rachel Hanna writes a very enjoyable experience with her January Cove tie. -

Krypt Guide 1 Mortal Kombat: Deception

Mortal Kombat: Deception Row A Koffin Requirements Reward AA 221 Sapphire koins Quan Chi’s Attack AB Krypt key Golden Desert Arena — Netherrealm E-2 AC 63 Sapphire koins 397 Gold koins AD 148 Platinum koins Edenia Realm Map AE 137 Platinum koins 371 Jade koins AF Krypt key Chou Jaio Video — Orderrealm B-6 AG 121 Ruby koins Puzzle Kombat Ladder AH 158 Ruby koins Torture Concept AI 201 Gold koins Kabal Story Board AJ 186 Sapphire koins Sindel’s Alt Bio AK 127 Sapphire koins Konquest Layout AL 223 Platinum koins Liu Kang’s Tomb Render AM Krypt key Nightwolf’s Alt Costume — Netherrealm A-4 AN 179 Sapphire koins Noob Story Board AO 612 OnyX koins Scorpion Kata Test AP 202 Platinum koins MK4 Scorpion Render AQ 352 Platinum koins Jade’s Alt Bio AR 192 Ruby koins Ermac Early Concept AS Krypt key Sub-Zero’s Alt Bio — Earthrealm C-3 AT 155 Platinum koins Sindel Story Board Krypt Guide 1 Mortal Kombat: Deception Row B Koffin Requirements Reward BA 193 Sapphire koins Kira Story Board BB 681 Platinum koins MK4 3D Test BC 108 Sapphire koins Dragon King Render BD 117 Gold koins 602 Sapphire koins BE 213 Platinum koins MK Chess Concept BF 113 OnyX koins Scorpion vs. Sub-Zero BG 352 Ruby koins 297 Sapphire koins Liu Kang’s Tomb Arena — Earthrealm H-6 BH Krypt key between 3am and 7am Liu Kang’s Bio — Earthrealm H-4 (beat BI Krypt key Konquest first) BJ 198 Gold koins Chamber Death Trap Concept BK 106 Platinum koins 4 Player Concept BL 87 Jade koins Evil Yin Yang Concept BM 97 Gold koins 659 Platinum koins BN 88 OnyX koins Nightwolf Concepts BO 269 Ruby -

8 Frames in 16Ms Rollback Networking in Mortal Kombat and Injustice

8 Frames in 16ms Rollback Networking in Mortal Kombat and Injustice Michael Stallone Lead Software Engineer – Engine NetherRealm Studios [email protected] What is this talk about? The how, why, and lessons learned from switching our network model from lockstep to rollback in a patch. Staffing • 4-12 concurrent engineers for 9 months • Roughly 7-8 man years for the initial release • Ongoing support is part time work for ~6 engineers Terminology • RTT Round trip time. Time a packet takes to travel from Client A > Client B > Client A • Network Latency One way packet travel time • Netpause Game pauses due to not receiving data from remote client for too long • QoS Quality of Service. Measurement of connection quality Terminology • Input Latency Injected delay between a button press and engine response • Confirm frame Most recent frame with input from all players • Desync Clients disagree about game state, leads to a disconnect • Dead Reckoning Networking model. Uses projections instead of resimulation Basics • Hard 60hz 1v1 fighting game • Peer to Peer • A network packet is sent once per frame • Standard networking tricks to hide packet loss Determinism The vast majority of our game loop is bit-for-bit deterministic. We “fencepost” many values at various points in the tick, and any divergence causes a desync. This is the foundation that everything is built on. The Problem Our online gameplay suffered from inconsistent (and high) input latency. The players were not happy. Latency Diagram Input Game CPU GPU Hardware OS Latency Sim Render Render Lockstep Only send gamepad data The game will not proceed until it has input from the remote player for the current frame Input is delayed by enough frames to cover the network latency Lockstep Current Frame Future Frames Player 1 1 2 3 Player 1 Pad Input X 8 Player 2 DO THIS DO THIS SLIDE SLIDE Player 2 1 2 3 The Present Mortal Kombat X and Injustice 2 have 3 frames of input latency and support up to 10 frames (333ms) of network latency before pausing the game. -

Download Injustice 1 Pc Download Injustice 1 Pc

download injustice 1 pc Download injustice 1 pc. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67d9216cfa93848c • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Injustice: Gods Among Us. Play your favorite character and compete against other gamers! The good news is that it is also available on Android and Xbox! Natalia Kudryavtseva Posts 1050 Registration date Wednesday April 15, 2020 Status Administrator Last seen August 12, 2021. Published by Warner Bros International Enterprises, Injustice: Gods Among Us is a popular action fighting game based on DC Comics Universe. The gamer can unleash superheroes’ abilities such as Batman, Joker, or Wonder Woman and fight enemies. There are different game modes available. This is the Injustice: Gods Among Us Ultimate Edition download page. Gaming features and gameplay. Injustice characters : Injustice: Gods Among Us features 24 characters, from Batman and Joker to Flash, Cyborg, Shazam, Green Lantern, and many others. With their help, you can defeat all the enemies. -

Manual Dead Island Riptide PC

© Copyright 2013 and Published by Deep Silver, a division of Koch Media GmbH, Gewerbegebiet 1, 6604 Höfen, Austria. Developed 2013, Techland Sp. z o.o., Poland. © Copyright 2013, Chrome Engine, Techland Sp. z o.o. All rights reserved. 1550110 Manual Dear Customer, Table of Contents Congratulations on purchasing this product from our company. We and the developers have done our best to provide you with Installation ....................................................................... 3 polished, interesting and entertaining software. We hope that it meets your expectations, and we would be pleased if you recommended it to Game Controls ................................................................ 3 your friends. Introduction to the Story .................................................... 4 If you are interested in our company’s other products or would like to Characters ...................................................................... 4 receive general information about our group of companies, please visit one of our websites: Character Info ................................................................. 4 www.kochmedia.com Character Selection .......................................................... 7 www.deepsilver.com Choosing a Character ...................................................... 7 We hope you enjoy your Koch Media product! Distribute Skill Points ......................................................... 8 Sincerely, The Koch Media Team Character Development ...................................................