Journalism As a Female Profession the Field Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965

Oral history interview with Roy Emerson Stryker, 1963-1965 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Roy Stryker on October 17, 1963. The interview took place in Montrose, Colorado, and was conducted by Richard Doud for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview Side 1 RICHARD DOUD: Mr. Stryker, we were discussing Tugwell and the organization of the FSA Photography Project. Would you care to go into a little detail on what Tugwell had in mind with this thing? ROY STRYKER: First, I think I'll have to raise a certain question about your emphasis on the word "Photography Project." During the course of the morning I gave you a copy of my job description. It might be interesting to refer back to it before we get through. RICHARD DOUD: Very well. ROY STRYKER: I was Chief of the Historical Section, in the Division of Information. My job was to collect documents and materials that might have some bearing, later, on the history of the Farm Security Administration. I don't want to say that photography wasn't conceived and thought of by Mr. Tugwell, because my backround -- as we'll have reason to talk about later -- and my work at Columbia was very heavily involved in the visual. -

The Saban Forum 2005

The Saban Forum 2005 A U.S.–Israel Dialogue Dealing with 21st Century Challenges Jerusalem, Israel November 11–13, 2005 The Saban Forum 2005 A U.S.–Israel Dialogue Dealing with 21st Century Challenges Jerusalem, Israel November 11–13, 2005 Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies Tel Aviv University Speakers and Chairmen Shai Agassi Shimon Peres Stephen Breyer Itamar Rabinovich David Brooks Aviezer Ravitzky William J. Clinton Condoleezza Rice Hillary Rodham Clinton Haim Saban Avi Dicter Ariel Sharon Thomas L. Friedman Zvi Shtauber David Ignatius Strobe Talbott Moshe Katsav Yossi Vardi Tzipi Livni Margaret Warner Shaul Mofaz James Wolfensohn Letter from the Chairman . 5 List of Participants . 6 Executive Summary . 9 Program Schedule . 19 Proceedings . 23 Katsav Keynote Address . 37 Clinton Keynote Address . 43 Sharon Keynote Address . 73 Rice Keynote Address . 83 Participant Biographies . 89 About the Saban Center . 105 About the Jaffee Center . 106 The ongoing tumult in the Middle East makes continued dialogue between the allied democracies of the United States and Israel all the more necessary and relevant. A Letter from the Chairman In November 2005, we held the second annual Saban Forum in Jerusalem. We had inaugurated the Saban Forum in Washington DC in December 2004 to provide a structured, institutional- ized annual dialogue between the United States and Israel. Each time we have gathered the high- est-level political and policy leaders, opinion formers and intellectuals to define and debate the issues that confront two of the world’s most vibrant democracies: the United States and Israel. The timing of the 2005 Forum could not have been more propitious or tragic. -

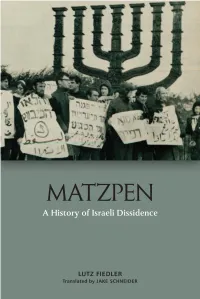

9781474451185 Matzpen Intro

MATZPEN A History of Israeli Dissidence Lutz Fiedler Translated by Jake Schneider 66642_Fiedler.indd642_Fiedler.indd i 331/03/211/03/21 44:35:35 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com Original version © Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, 2017 English translation © Jake Schneider, 2020 Edinburgh University Press Ltd Th e Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/15 Adobe Garamond by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 5116 1 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 5118 5 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 5119 2 (epub) Th e right of Lutz Fiedler to be identifi ed as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Originally published in German as Matzpen. Eine andere israelische Geschichte (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017) Th e translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International – Translation Funding for Work in the Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Th yssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Offi ce, the collecting society VG WORT and the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association). -

Posing, Candor, and the Realisms of Photographic Portraiture, 1839-1945

Posing, Candor, and the Realisms of Photographic Portraiture, 1839-1945 Jennifer Elizabeth Anne Rudd Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 i © 2014 Jennifer Elizabeth Anne Rudd All rights reserved ii Abstract Posing, Candor, and the Realisms of Photographic Portraiture, 1839-1945 Jennifer Elizabeth Anne Rudd This study offers a history of the concept of realism in portrait photography through the examination of a set of categories that have colored photographic practices since the origins of the medium in 1839: the posed and the candid. The first section of this study deals with the practices of posing in early photography, with chapters on the daguerreotype, the carte de visite, and the amateur snapshot photograph. Considering technological advances in conjunction with prevailing cultural mores and aesthetic practices, this section traces the changing cultural meaning of the portrait photograph, the obsolescence of the pose, and the emergence of an “unposed” aesthetic in photography. The second section of this study examines three key photographers and their strategies of photographic representation, all of which involved candid photography: it looks at Erich Salomon’s pioneering photojournalism, Humphrey Spender’s politicized sociological photography, and Walker Evans’ complex maneuvering of the documentary form. Here, the emphasis is on the ways in which the trope of the candid informed these three distinct spheres of photography in the early 20th century, and the ways in which the photographic aesthetic of candor cohered with—or contested—political and cultural developments of the interwar period in Germany, Britain, and the United States. -

Israel Update

Israel and the Middle East News Update Thursday, September 15 Headlines: Touting Aid Deal, Obama Says Israeli Security Requires Palestinian State PM's Former Security Advisor Slams Handling of U.S. Military Aid Deal Peres Remains in Serious, But Stable Condition Hundreds of Israeli Intellectuals: ‘End Occupation for Israel’s Sake’ Lieberman Orders Israeli Defense, Military Officials to Boycott UN Envoy US General: Israel Is Key to Fighting World's Terrorism Problem Gaza Rockets Land in Southern Israel Prompting IDF Targeted Response Saudi Prince Warns Iran Against Using Force to Pursue Rivalry Commentary: Washington Post: “Ehud Barak: Bibi’s Reckless Conduct Endangers Israel” By Ehud Barak, Former Israeli Prime Minister (’99-’01) & Defense Minister (‘99-’01, ’07-’13) Yedioth Ahronoth: “The Secret Commitment” By Nahum Barnea, Leading Israeli Journalist, Yedioth Ahronoth S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace 633 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20004 www.centerpeace.org ● Yoni Komorov, Editor ● David Abreu, Associate Editor News Excerpts September 15, 2016 Times of Israel Obama: True Israeli Security Requires Palestinian Statehood U.S. President Barack Obama said Wednesday that while the massive new military aid deal for Israel — Washington’s largest defense package to any country in history — would help Israel defend itself, “long-term security” can only be achieved by the creation of “an independent and viable Palestine.” In a statement released shortly after the signing, Obama described the memorandum of understanding as “just the most recent reflection of my steadfast commitment to the security of the State of Israel,” citing billions of dollars provided by his administration over the past eight years. -

Oral History Interview with Ben Shahn, 1964 April 14

Oral history interview with Ben Shahn, 1964 April 14 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Ben Shahn on April 14, 1964. The interview was conducted at Ben Shahn's home in Roosevelt, New Jersey by Richard Doud for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview RICHARD DOUD: I'd like to start with a general background of what you were doing prior to the time and how you managed to get with the Resettlement Program. BEN SHAHN: Well, I told you I shared a studio with Walker Evans before any of this came along. I became interested in photography when I found my own sketching was inadequate. I was at that time very interested in anything that had details, you know, I remember one thing, I was working around 14th Street and that group of blind musicians were constantly playing there, I would walk in front of them and sketch, and walk backwards and sketch and I found it was inadequate. So I asked by brother to buy me a camera because I didn't have the money for it. He bought me a Leica and I promised him - this was kind of a bold promise - I said, "If I don't get in a magazine off the first roll you can have your camera back." I did get into a magazine, a theater magazine at the time. -

The U.S.-Turkey-Israel Triangle

ANALYSIS PAPER Number 34, October 2014 THE U.S.-TURKEY-ISRAEL TRIANGLE Dan Arbell The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2014 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036 www.brookings.edu Acknowledgements I would like to thank Haim and Cheryl Saban for their support of this re- search. I also wish to thank Tamara Cofman Wittes for her encouragement and interest in this subject, Dan Byman for shepherding this process and for his continuous sound advice and feedback, and Stephanie Dahle for her ef- forts to move this manuscript through the publication process. Thank you to Martin Indyk for his guidance, Dan Granot and Clara Schein- mann for their assistance, and a special thanks to Michael Oren, a mentor and friend, for his strong support. Last, but not least, I would like to thank my wife Sarit; without her love and support, this project would not have been possible. The U.S.-Turkey-Israel Triangle The Center for Middle East Policy at BROOKINGS ii About the Author Dan Arbell is a nonresident senior fellow with Israel’s negotiating team with Syria (1993-1996), the Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings, and later as deputy chief of mission at the Israeli and a scholar-in-residence with the department of Embassy in Tokyo, Japan (2001-2005). -

The Inventory of the Carleton Beals Collection #1347

The Inventory of the Carleton Beals Collection #1347 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Beals, Carleton (1893-1979) #1347 Gift of Mrs. Carleton Beals Outline of Inventory I. Manuscripts, Boxes # 1-106. A. Published Books: Non-Fiction. B. Record Album Text. C. Translation. D. Published Novel. E. Published Articles. F. Published Short Stories. G. Unpublished Autobiography. H. Unpublished Non-Fiction. I. Shorter Book Manuscripts. J. Unpublished Articles. K. News Dispatches. L. Book Projects. M. Unpublished Fiction: Books. N. Unpublished Fiction: Short Stories. O. Plays. P. Poetry. Q. Fillers. R. Manuscripts by Other Authors. S. Various Unidentified Drafts. 2 II. Printed Matter, Boxes # 107-119. A. Tearsheets. B. Research Files, Boxes # 120-142. C. Personal Files, Boxes # 143-158. III. Photographs, Boxes # 159-164. IV. Correspondence, Boxes # 165-199. Personal and Professional (Chronological), 1916-May 1979. Addenda, June 17, 1981, Box # 200. 3 Beals, Carleton #1347 Gift of Mrs. Carleton Beals December 1979 Box 1 I. Manuscripts. A. Published Books: Non-Fiction. 1. ADVENTURE OF THE WESTERN SEA: THE STORY OF ROBERT GRAY, Holt, 1956. Folders 1-2 a. TS with holograph corrections, 2 versions, 133 p. each (cover illus. included). Folders 3-4 b. CTS draft, 199 p. 2. BRASS-KNUCKLE CRUSADE: THE GREAT KNOW-NOTHING CONSPIRACY, Hastings House, 1960. Folders 5-7 a. Setting copy with proofreader's marks; 393 p., bibliography. Folders 8-9 b. Various TS draft pages (incomplete). Box 2 3. COLONIAL RHODE ISLAND. Folders 1-5 a. Various TS draft pages. 4 Box 2 cont=d. Folders 6-8 b. Holograph and TS draft pages. Folder 9 c. -

American Road Photography from 1930 to the Present A

THE PROFANE AND PROFOUND: AMERICAN ROAD PHOTOGRAPHY FROM 1930 TO THE PRESENT A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Han-Chih Wang Diploma Date August 2017 Examining Committee Members: Professor Gerald Silk, Department of Art History Professor Miles Orvell, Department of English Professor Erin Pauwels, Department of Art History Professor Byron Wolfe, Photography Program, Department of Graphic Arts and Design THE PROFANE AND PROFOUND: AMERICAN ROAD PHOTOGRAPHY FROM 1930 TO THE PRESENT ABSTRACT Han-Chih Wang This dissertation historicizes the enduring marriage between photography and the American road trip. In considering and proposing the road as a photographic genre with its tradition and transformation, I investigate the ways in which road photography makes artistic statements about the road as a visual form, while providing a range of commentary about American culture over time, such as frontiersmanship and wanderlust, issues and themes of the automobile, highway, and roadside culture, concepts of human intervention in the environment, and reflections of the ordinary and sublime, among others. Based on chronological order, this dissertation focuses on the photographic books or series that depict and engage the American road. The first two chapters focus on road photographs in the 1930s and 1950s, Walker Evans’s American Photographs, 1938; Dorothea Lange’s An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion, 1939; and Robert Frank’s The Americans, 1958/1959. Evans dedicated himself to depicting automobile landscapes and the roadside. Lange concentrated on documenting migrants on the highway traveling westward to California. -

Kommunikationswissenschaft: Massenkommunikation - Medien - Sprache

soFid Sozialwissenschaftlicher Fachinformationsdienst Kommunikationswissenschaft: Massenkommunikation - Medien - Sprache 2010|2 Kommunikationswissenschaft Massenkommunikation - Medien - Sprache Sozialwissenschaftlicher Fachinformationsdienst soFid Kommunikationswissenschaft Massenkommunikation - Medien - Sprache Band 2010/2 bearbeitet von Hannelore Schott GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften 2010 ISSN: 1431-1038 Herausgeber: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Abteilung Fachinformation für Sozialwissenschaften (FIS) bearbeitet von: Hannelore Schott Programmierung: Siegfried Schomisch Druck u. Vertrieb: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften Lennéstr. 30, 53113 Bonn, Tel.: (0228)2281-0 Printed in Germany Die Mittel für diese Veröffentlichung wurden im Rahmen der institutionellen Förderung von GESIS durch den Bund und die Länder gemeinsam bereitgestellt. © 2010 GESIS. Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Insbesondere ist die Überführung in maschinenlesbare Form sowie das Speichern in Informationssystemen, auch auszugsweise, nur mit schriftlicher Ein- willigung des Herausgebers gestattet. Inhalt Vorwort .................................................................................................................................................7 Sachgebiete 1 Massenkommunikation 1.1 Allgemeines...............................................................................................................................9 1.2 Geschichte der Medien, Pressegeschichte...............................................................................24 -

Episodes from the History of American-Soviet Cultural Relations: Stanford Slavic Studies, Volume 5 (1992)

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Faculty Publications 4-8-2020 Episodes from the History of American-Soviet Cultural Relations: Stanford Slavic Studies, Volume 5 (1992) Lazar Fleishman [email protected] Ronald D. LeBlanc (Translator) University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Fleishman, Lazar, "Episodes from the History of American-Soviet Cultural Relations: Stanford Slavic Studies, Volume 5 (1992)," translated by LeBlanc, Ronald D. (2020). Faculty Publications. 790. https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/790 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lazar Fleishman Episodes from the History of American-Soviet Cultural Relations Stanford Slavic Studies, Volume 5 (1992) translated by Ronald D. LeBlanc 1 Author’s Foreword The present volume may be viewed as an idiosyncratic sequel to the book, Russkii Berlin [Russian Berlin], which I – along with Olga Raevskaia-Hughes and Robert Hughes – prepared for publication and then published in 1983. It grows directly out of the work that was begun by the three of us at that time (work that I recall with a feeling of ardent gratitude) and is likewise based entirely upon materials on Russian literature and culture that are housed in a single, but extraordinarily valuable, collection – the archive of the Hoover Institution. As was true in that earlier case, this archive consists of materials that outwardly appear to be heterogeneous, materials, furthermore, that relate to what are decidedly divergent stages in the history of Russian culture – the prerevolutionary stage in the first section (the “Gorky” section) and the Soviet stage in the second section. -

August 11 2017

Israel and the Middle East News Update Friday, August 11 Headlines: • TV Poll: 'Only 33% Believe Netanyahu is Innocent’ • Ex-Diplomats: PM’s Trouble Hardly Affect Trump’s Peace Push • Israel Warns Hamas Not to Try to Foil its Anti-Tunnel Wall • Iranian Journalist Seeking Asylum Finds Refuge in Israel • Israel, Jordan, PA to Hold First Joint Firefighting Exercise • PA President Abbas Curbs Social Media Freedom in Decree • Police May Stop Protests at Attorney General’s House • New Israeli Air Force Commander Sworn In Commentary: • Yediot Ahronot: “A Knight for a King” - By Nahum Barnea, senior columnist at Yediot Ahronot • New York Times: “Israel’s Getting a New Wall, This One With a Twist” - By Isabel Kershner, Israel and PA Correspondent at The New York Times S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace 633 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20004 www.centerpeace.org ● Yoni Komorov, Editor ● David Abreu, Associate Editor News Excerpts August 11, 2017 Jerusalem Post TV Poll: 'Only 33% Believe Netanyahu is Innocent’ Prime Minister Netanyahu’s address to Likud on Wednesday did not succeed in persuading the public of his innocence, according to a poll taken for Channel 1 on Thursday. The poll found that only 33% of Israelis believe Netanyahu is innocent, among whom 25% said they somewhat believe in his innocence and only 8% said they strongly believed he was innocent. Two-thirds said they do not believe he is innocent, including 29% who said they did not believe at all, and 38% who said they somewhat did not believe. Asked whether the speech strengthened or weakened their belief in Netanyahu’s innocence, 8% said it strengthened it, 2% said it weakened it, 46% said their opinion remained unchanged.