The Memory Hierarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

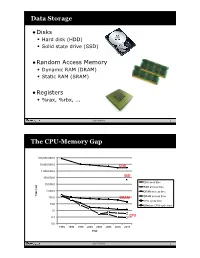

Data Storage the CPU-Memory

Data Storage •Disks • Hard disk (HDD) • Solid state drive (SSD) •Random Access Memory • Dynamic RAM (DRAM) • Static RAM (SRAM) •Registers • %rax, %rbx, ... Sean Barker 1 The CPU-Memory Gap 100,000,000.0 10,000,000.0 Disk 1,000,000.0 100,000.0 SSD Disk seek time 10,000.0 SSD access time 1,000.0 DRAM access time Time (ns) Time 100.0 DRAM SRAM access time CPU cycle time 10.0 Effective CPU cycle time 1.0 0.1 CPU 0.0 1985 1990 1995 2000 2003 2005 2010 2015 Year Sean Barker 2 Caching Smaller, faster, more expensive Cache 8 4 9 10 14 3 memory caches a subset of the blocks Data is copied in block-sized 10 4 transfer units Larger, slower, cheaper memory Memory 0 1 2 3 viewed as par@@oned into “blocks” 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 3 Cache Hit Request: 14 Cache 8 9 14 3 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 4 Cache Miss Request: 12 Cache 8 12 9 14 3 12 Request: 12 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 5 Locality ¢ Temporal locality: ¢ Spa0al locality: Sean Barker 6 Locality Example (1) sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < n; i++) sum += a[i]; return sum; Sean Barker 7 Locality Example (2) int sum_array_rows(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < M; i++) for (j = 0; j < N; j++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 8 Locality Example (3) int sum_array_cols(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (j = 0; j < N; j++) for (i = 0; i < M; i++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 9 The Memory Hierarchy The Memory Hierarchy Smaller On 1 cycle to access CPU Chip Registers Faster Storage Costlier instrs can L1, L2 per byte directly Cache(s) ~10’s of cycles to access access (SRAM) Main memory ~100 cycles to access (DRAM) Larger Slower Flash SSD / Local network ~100 M cycles to access Cheaper Local secondary storage (disk) per byte slower Remote secondary storage than local (tapes, Web servers / Internet) disk to access Sean Barker 10. -

Managing the Memory Hierarchy

Managing the Memory Hierarchy Jeffrey S. Vetter Sparsh Mittal, Joel Denny, Seyong Lee Presented to SOS20 Asheville 24 Mar 2016 ORNL is managed by UT-Battelle for the US Department of Energy http://ft.ornl.gov [email protected] Exascale architecture targets circa 2009 2009 Exascale Challenges Workshop in San Diego Attendees envisioned two possible architectural swim lanes: 1. Homogeneous many-core thin-node system 2. Heterogeneous (accelerator + CPU) fat-node system System attributes 2009 “Pre-Exascale” “Exascale” System peak 2 PF 100-200 PF/s 1 Exaflop/s Power 6 MW 15 MW 20 MW System memory 0.3 PB 5 PB 32–64 PB Storage 15 PB 150 PB 500 PB Node performance 125 GF 0.5 TF 7 TF 1 TF 10 TF Node memory BW 25 GB/s 0.1 TB/s 1 TB/s 0.4 TB/s 4 TB/s Node concurrency 12 O(100) O(1,000) O(1,000) O(10,000) System size (nodes) 18,700 500,000 50,000 1,000,000 100,000 Node interconnect BW 1.5 GB/s 150 GB/s 1 TB/s 250 GB/s 2 TB/s IO Bandwidth 0.2 TB/s 10 TB/s 30-60 TB/s MTTI day O(1 day) O(0.1 day) 2 Memory Systems • Multimode memories – Fused, shared memory – Scratchpads – Write through, write back, etc – Virtual v. Physical, paging strategies – Consistency and coherence protocols • 2.5D, 3D Stacking • HMC, HBM/2/3, LPDDR4, GDDR5, WIDEIO2, etc https://www.micron.com/~/media/track-2-images/content-images/content_image_hmc.jpg?la=en • New devices (ReRAM, PCRAM, Xpoint) J.S. -

Embedded DRAM

Embedded DRAM Raviprasad Kuloor Semiconductor Research and Development Centre, Bangalore IBM Systems and Technology Group DRAM Topics Introduction to memory DRAM basics and bitcell array eDRAM operational details (case study) Noise concerns Wordline driver (WLDRV) and level translators (LT) Challenges in eDRAM Understanding Timing diagram – An example References Slide 1 Acknowledgement • John Barth, IBM SRDC for most of the slides content • Madabusi Govindarajan • Subramanian S. Iyer • Many Others Slide 2 Topics Introduction to memory DRAM basics and bitcell array eDRAM operational details (case study) Noise concerns Wordline driver (WLDRV) and level translators (LT) Challenges in eDRAM Understanding Timing diagram – An example Slide 3 Memory Classification revisited Slide 4 Motivation for a memory hierarchy – infinite memory Memory store Processor Infinitely fast Infinitely large Cycles per Instruction Number of processor clock cycles (CPI) = required per instruction CPI[ ∞ cache] Finite memory speed Memory store Processor Finite speed Infinite size CPI = CPI[∞ cache] + FCP Finite cache penalty Locality of reference – spatial and temporal Temporal If you access something now you’ll need it again soon e.g: Loops Spatial If you accessed something you’ll also need its neighbor e.g: Arrays Exploit this to divide memory into hierarchy Hit L2 L1 (Slow) Processor Miss (Fast) Hit Register Cache size impacts cycles-per-instruction Access rate reduces Slower memory is sufficient Cache size impacts cycles-per-instruction For a 5GHz -

The Memory Hierarchy

Chapter 6 The Memory Hierarchy To this point in our study of systems, we have relied on a simple model of a computer system as a CPU that executes instructions and a memory system that holds instructions and data for the CPU. In our simple model, the memory system is a linear array of bytes, and the CPU can access each memory location in a constant amount of time. While this is an effective model as far as it goes, it does not reflect the way that modern systems really work. In practice, a memory system is a hierarchy of storage devices with different capacities, costs, and access times. CPU registers hold the most frequently used data. Small, fast cache memories nearby the CPU act as staging areas for a subset of the data and instructions stored in the relatively slow main memory. The main memory stages data stored on large, slow disks, which in turn often serve as staging areas for data stored on the disks or tapes of other machines connected by networks. Memory hierarchies work because well-written programs tend to access the storage at any particular level more frequently than they access the storage at the next lower level. So the storage at the next level can be slower, and thus larger and cheaper per bit. The overall effect is a large pool of memory that costs as much as the cheap storage near the bottom of the hierarchy, but that serves data to programs at the rate of the fast storage near the top of the hierarchy. -

Lecture 10: Memory Hierarchy -- Memory Technology and Principal of Locality

Lecture 10: Memory Hierarchy -- Memory Technology and Principal of Locality CSCE 513 Computer Architecture Department of Computer Science and Engineering Yonghong Yan [email protected] https://passlab.github.io/CSCE513 1 Topics for Memory Hierarchy • Memory Technology and Principal of Locality – CAQA: 2.1, 2.2, B.1 – COD: 5.1, 5.2 • Cache Organization and Performance – CAQA: B.1, B.2 – COD: 5.2, 5.3 • Cache Optimization – 6 Basic Cache Optimization Techniques • CAQA: B.3 – 10 Advanced Optimization Techniques • CAQA: 2.3 • Virtual Memory and Virtual Machine – CAQA: B.4, 2.4; COD: 5.6, 5.7 – Skip for this course 2 The Big Picture: Where are We Now? Processor Input Control Memory Datapath Output • Memory system – Supplying data on time for computation (speed) – Large enough to hold everything needed (capacity) 3 Overview • Programmers want unlimited amounts of memory with low latency • Fast memory technology is more expensive per bit than slower memory • Solution: organize memory system into a hierarchy – Entire addressable memory space available in largest, slowest memory – Incrementally smaller and faster memories, each containing a subset of the memory below it, proceed in steps up toward the processor • Temporal and spatial locality insures that nearly all references can be found in smaller memories – Gives the allusion of a large, fast memory being presented to the processor 4 Memory Hierarchy Memory Hierarchy 5 Memory Technology • Random Access: access time is the same for all locations • DRAM: Dynamic Random Access Memory – High density, low power, cheap, slow – Dynamic: need to be “refreshed” regularly – 50ns – 70ns, $20 – $75 per GB • SRAM: Static Random Access Memory – Low density, high power, expensive, fast – Static: content will last “forever”(until lose power) – 0.5ns – 2.5ns, $2000 – $5000 per GB Ideal memory: • Magnetic disk • Access time of SRAM – 5ms – 20ms, $0.20 – $2 per GB • Capacity and cost/GB of disk 6 Static RAM (SRAM) 6-Transistor Cell – 1 Bit 6-Transistor SRAM Cell word word 0 1 (row select) 0 1 bit bit bit bit • Write: 1. -

Chapter 2: Memory Hierarchy Design

Computer Architecture A Quantitative Approach, Fifth Edition Chapter 2 Memory Hierarchy Design Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Contents 1. Memory hierarchy 1. Basic concepts 2. Design techniques 2. Caches 1. Types of caches: Fully associative, Direct mapped, Set associative 2. Ten optimization techniques 3. Main memory 1. Memory technology 2. Memory optimization 3. Power consumption 4. Memory hierarchy case studies: Opteron, Pentium, i7. 5. Virtual memory 6. Problem solving dcm 2 Introduction Introduction Programmers want very large memory with low latency Fast memory technology is more expensive per bit than slower memory Solution: organize memory system into a hierarchy Entire addressable memory space available in largest, slowest memory Incrementally smaller and faster memories, each containing a subset of the memory below it, proceed in steps up toward the processor Temporal and spatial locality insures that nearly all references can be found in smaller memories Gives the allusion of a large, fast memory being presented to the processor Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 3 Memory hierarchy Processor L1 Cache L2 Cache L3 Cache Main Memory Latency Hard Drive or Flash Capacity (KB, MB, GB, TB) Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 4 PROCESSOR L1: I-Cache D-Cache I-Cache instruction cache D-Cache data cache U-Cache unified cache L2: U-Cache Different functional units fetch information from I-cache and D-cache: decoder and L3: U-Cache scheduler operate with I- cache, but integer execution unit and floating-point unit Main: Main Memory communicate with D-cache. Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. -

Memory Hierarchy Summary

Carnegie Mellon Carnegie Mellon Today DRAM as building block for main memory The Memory Hierarchy Locality of reference Caching in the memory hierarchy Storage technologies and trends 15‐213 / 18‐213: Introduction to Computer Systems 10th Lecture, Feb 14, 2013 Instructors: Seth Copen Goldstein, Anthony Rowe, Greg Kesden 1 2 Carnegie Mellon Carnegie Mellon Byte‐Oriented Memory Organization Simple Memory Addressing Modes Normal (R) Mem[Reg[R]] • • • . Register R specifies memory address . Aha! Pointer dereferencing in C Programs refer to data by address movl (%ecx),%eax . Conceptually, envision it as a very large array of bytes . In reality, it’s not, but can think of it that way . An address is like an index into that array Displacement D(R) Mem[Reg[R]+D] . and, a pointer variable stores an address . Register R specifies start of memory region . Constant displacement D specifies offset Note: system provides private address spaces to each “process” . Think of a process as a program being executed movl 8(%ebp),%edx . So, a program can clobber its own data, but not that of others nd th From 2 lecture 3 From 5 lecture 4 Carnegie Mellon Carnegie Mellon Traditional Bus Structure Connecting Memory Read Transaction (1) CPU and Memory CPU places address A on the memory bus. A bus is a collection of parallel wires that carry address, data, and control signals. Buses are typically shared by multiple devices. Register file Load operation: movl A, %eax ALU %eax CPU chip Main memory Register file I/O bridge A 0 Bus interface ALU x A System bus Memory bus I/O Main Bus interface bridge memory 5 6 Carnegie Mellon Carnegie Mellon Memory Read Transaction (2) Memory Read Transaction (3) Main memory reads A from the memory bus, retrieves CPU read word xfrom the bus and copies it into register word x, and places it on the bus. -

Memory Hierarchy

Memory The Memory/Processor Performance Gap Memory-Processor Performance Gap The memory hierarchy CPU Increasing distance Level 1 from the CPU in access time Levels in the Level 2 memory hierarchy Level n Size of the memory at each level The memory hierarchy Fundamentals of Memory Hierarchy Locality Temporal locality The currently required data are likely to need again in the near future Spatial locality There is high probability that the other data nearby will be need soon Two Processor/Memory Architectures Processor Processor Princeton Fewer memory wires Harvard Program Data memory Memory Simultaneous memory (program and data) program and data memory access Harvard Princeton Memory Access Process Physical Address Virtual Tag address hit miss CPU Main TLB Cache Memory miss hit Address Translation data TLB (Translation lookaside buffer): Translate a virtual address to a physical address Memory management units Handles DRAM refresh, bus interface and arbitration Takes care of memory sharing among multiple processors Translates logic memory addresses from processor to physical memory addresses logical physical address memory address main CPU management memory unit Memory Data Organization Endianness Big Endian/Little Endian Memory data alignment Endianness The order of bytes (sometimes “bit”) in memory to represent different data types Little/Big Endian Little Endian: put the least-significant byte first (at lower address) e.g. Intel Processor Big Endian: put the most-significant byte first e.g.some PowerPCs, Motorola, -

Memory Hierarchy Design

Chapter 2 CPU vs. Memory: Performance vs Latency Memory Hierarchy Design 4 Introduction Memory Hierarchy Design Considerations ● Goal: unlimited amount of memory with low latency ● Fast memory technology is more expensive per bit than ● Memory hierarchy design becomes more crucial with recent slower memory multi-core processors: – Use principle of locality (spatial and temporal) – Aggregate peak bandwidth grows with # cores: ● Solution: organize memory system into a hierarchy ● Intel Core i7 can generate two references per core per clock ● Four cores and 3.2 GHz clock – Entire addressable memory space available in largest, slowest memory – 25.6 billion 64-bit data references/second + – 12.8 billion 128-bit instruction references – Incrementally smaller and faster memories, each containing a – = 409.6 GB/s! subset of the memory below it, proceed in steps up toward the ● DRAM bandwidth is only 6% of this (25 GB/s) processor ● Requires: ● Temporal and spatial locality insures that nearly all – Multi-port, pipelined caches references can be found in smaller memories – Two levels of cache per core – Shared third-level cache on chip – Gives the illusion of a large, fast memory being presented to the processor 2 5 Memory Hierarchies Performance and Power for Caches CPU CPU Registers 1000 B 300 ps Registers 500 B 500 ps L1 L1 64 kB 1 ns 64 kB 2 ns On-die L2 256 kB 3-10 ns L2 256 kB 10-20 ns ● High-end microprocessors have >10 MB on-chip cache 2-4 MB 10-20 ns – Consumes large amount of area and power budget L3 In package – Both static (idle) and -

Memory Hierarchy

ECE 550D Fundamentals of Computer Systems and Engineering Fall 2016 Memory Hierarchy Tyler Bletsch Duke University Slides are derived from work by Andrew Hilton (Duke) and Amir Roth (Penn) Memory Hierarchy App App App • Basic concepts System software • Technology background Mem CPU I/O • Organizing a single memory component • ABC • Write issues • Miss classification and optimization • Organizing an entire memory hierarchy • Virtual memory • Highly integrated into real hierarchies, but… • …won’t talk about until later 2 How Do We Build Insn/Data Memory? intRF PC IM DM • Register file? Just a multi-ported SRAM • 32 32-bit registers = 1Kb = 128B • Multiple ports make it bigger and slower but still OK • Insn/data memory? Just a single-ported SRAM? • Uh, umm… it’s 232B = 4GB!!!! – It would be huge, expensive, and pointlessly slow – And we can’t build something that big on-chip anyway • Most ISAs now 64-bit, so memory is 264B = 16EB 3 So What Do We Do? Actually… intRF PC IM DM 64KB 16KB • “Primary” insn/data memory are single-ported SRAMs… • “primary” = “in the datapath” • Key 1: they contain only a dynamic subset of “memory” • Subset is small enough to fit in a reasonable SRAM • Key 2: missing chunks fetched on demand (transparent to program) • From somewhere else… (next slide) • Program has illusion that all 4GB (16EB) of memory is physically there • Just like it has the illusion that all insns execute atomically 4 But… intRF PC IM DM 64KB 16KB 4GB(16EB)? • If requested insn/data not found in primary memory • Doesn’t the place it comes from -

The Lower Levels of the Memory Hierarchy: Storage Systems

C SCI 360 Computer Architecture 3 Prof. Stewart Weiss The Lower Levels of the Memory Hierarchy: Storage Systems The Lower Levels of the Memory Hierarchy: Storage Systems Overview We use the term storage system to describe persistent memory, meaning memory devices that retain information when power is not applied, such as magnetic disks, magnetic tapes, optical disks of various kinds, and flash memory devices. The concepts of input and output have traditionally been used to refer to the transfer of data from non-persistent internal stores, i.e., memory, and storage systems or devices used to receive data from transient sources (keyboards, networks) or to display data on a transient device (monitors and other visual displays). Although in theory the transfer of data between levels of a hierarchy can be treated in a uniform way, in practice, there are significantly different issues when data has to migrate to or from devices or be stored on them. Because we use storage systems to preserve our data for us, it is of the utmost importance that we can depend upon them to do so. This concept of dependability will be made precise shortly. The standard for dependability is higher for storage systems than it is for computation. It is one thing for a processor to hang or even crash, but another if a hard disk fails. A processor crash is usually just an inconvenience but a disk failure might mean irreplaceable data loss. Therefore, storage systems place greater emphasis on: • dependability • cost • expandability Figure 1: Typical collection of storage and I/O devices than they do on performance. -

14. Caches & the Memory Hierarchy

14. Caches & The Memory Hierarchy 6.004x Computation Structures Part 2 – Computer Architecture Copyright © 2016 MIT EECS 6.004 Computation Structures L14: Caches & The Memory Hierarchy, Slide #1 Memory Our “Computing Machine” ILL XAdr OP JT 4 3 2 1 0 PCSEL Reset RESET 1 0 We need to fetch one instruction each cycle PC 00 A Instruction Memory +4 D ID[31:0] Ra: ID[20:16] Rb: ID[15:11] Rc: ID[25:21] 0 1 RA2SEL + WASEL Ultimately RA1 RA2 XP 1 Register WD Rc: ID[25:21] WAWA data is 0 File RD1 RD2 WE WE R F Z JT loaded C: SXT(ID[15:0]) (PC+4)+4*SXT(C) from and IRQ Z ID[31:26] ASEL 1 0 1 0 BSEL results Control Logic stored to ALUFN ASEL memory BSEL A B MOE WD WE MWR ALUFN ALU MWR Data MOE OE PCSEL Memory RA2SEL Adr RD WASEL WDSEL WERF PC+4 0 1 2 WD S E L 6.004 Computation Structures L14: Caches & The Memory Hierarchy, Slide #2 Memory Technologies Technologies have vastly different tradeoffs between capacity, access latency, bandwidth, energy, and cost – … and logically, different applications Capacity Latency Cost/GB Processor Register 1000s of bits 20 ps $$$$ Datapath SRAM ~10 KB-10 MB 1-10 ns ~$1000 Memory DRAM ~10 GB 80 ns ~$10 Hierarchy Flash* ~100 GB 100 us ~$1 I/O Hard disk* ~1 TB 10 ms ~$0.10 subsystem * non-volatile (retains contents when powered off) 6.004 Computation Structures L14: Caches & The Memory Hierarchy, Slide #3 Static RAM (SRAM) Data in Drivers 6 SRAM cell Wordlines Address (horizontal) 3 Bitlines (vertical, two per cell) Address decoder 8x6 SRAM Sense array amplifiers 6 6.004 Computation Structures Data out L14: Caches & The Memory Hierarchy, Slide #4 SRAM Cell 6-MOSFET (6T) cell: – Two CMOS inverters (4 MOSFETs) forming a bistable element – Two access transistors Bistable element bitline bitline (two stable states) stores a single bit 6T SRAM Cell Vdd GND “1” GND Vdd “0” Wordline N access FETs 6.004 Computation Structures L14: Caches & The Memory Hierarchy, Slide #5 SRAM Read 1 1.