Causes for Professionalization in National Sport Federations in Switzerland: a Multiple-Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

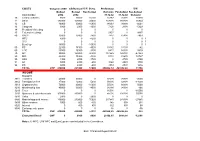

Total Assets Total Liabilities & Equity

Financial Report 2007 Congress Updated Balance sheet 2007 Appendix 2 COSTS Budget Budget Outcome Outcome Cost Centre 30.04.2007 /Ann.budget 10 Central activities 13000 12000 7848,93 4151 ASSETS 11 Office 470000 432400 152050,44 280350 01.01.2007 30.04.2007 12 CB 40000 42750 3014,50 39736 Current assets 13 Congress 0 0 0,00 0 Cash 0,00 0,00 14 President's Meeting 2000 2000 0,00 2000 Credit Suisse 559200-11 597964,09 602450,89 15 External meetings 5000 7250 970,75 6279 16 IOC 50 Road Map 0 26000 0,00 Receivables 20 WFC 8000 8000 8649,64 -650 Claims 2005 35900,00 23900,00 21 U19 WFC 12000 12000 1517,62 10482 Claims 2006 158149,16 26000,00 22 EFC 11500 11500 24,87 11475 Claims 2007 0,00 62509,02 25 WUC 0 0 0,00 0 Deferr expenses and accr income 0,00 0,00 40 RACC 18000 16400 0,00 16400 Receivables from rel.parties 1400,25 541,53 50 RC 26000 28500 0,00 28500 Total assets 793413,50 715401,44 60 Development 17500 14300 609,01 13691 61 Development programme 58000 47300 7006,31 40294 LIABILITIES AND EQUITY 70 Material 150000 148500 405,38 148095 80 Marketing 40000 34400 2793,60 31606 Current liabilities 81 TV 14000 14000 0,00 Accr expenses and deferr income -183000,00 -78000,00 89 MC 0 4600 1045,05 3555 Other current liabilities 0,00 0,00 91 AC 2600 2300 0,00 2300 Transfers to reserves -153231,22 -67128,81 92 DC 2600 2300 0,00 2300 Development Board reserves 2005 -43636,78 -43636,78 TOTAL CHF 890200 866500 185936,10 680564 Development Board reserves 2006 -49874,19 -49874,19 Development Board reserves 2007 0,00 0,00 INCOME Congress Updated Equity -

Candidature Dossier 8 World

CANDIDATURE DOSSIER 8TH WORLD FLOORBALL CHAMPIONSHIP WOMEN 2011 22ND – 29TH MAY 2011 WINTERTHUR, SWITZERLAND CANDIDATUR DOSSIER 8th World Floorball Championship Women 2011 FACT-SHEET Designation: 8th World Floorball Championship Women 2011 Organiser: Swiss Unihockey Date: 22nd to 29th May 2011 Arrival: Saturday, 21.05.2011 Opening: Sunday, 22.05.2011 Final day: Sunday, 29.05.2011 Venue: Winterthur Sports arena: Eulachhalle Winterthur for all matches Capacity: Main hall 2300 seats Training hall: Yet to be defined Accommodation: Winterthur and environment have a wide range of accommodation possibilities in all price ranges Transport: Winterthur has ideal connections by all means of transport. Funding: The World Championship will be funded by the Confedera- tion, the canton and the town of Winterthur. In addition the event is being professionally marketed. Support: Swiss Olympic Association The Federal Office of Sport, Macolin The Authorities of the Canton of Zurich The Authorities of the City of Winterthur Swiss Unihockey CANDIDATURE DOSSIER CANDIDATUR DOSSIER 8th World Floorball Championship Women 2011 GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT WINTERTHUR Winterthur is a town of over 96'000 inhabitants and is in the region of Greater Zurich. It is the sixth-largest city in Switzerland and forms its own economic, cul- tural and political centre. It is an attractive little town, which offers great variety on a human scale and thus a great quality of life for its population. It has excellent traffic connections to the Swiss railway network, to the Zurich rapid-transit railway and to the airport. The excellent housing situation with large green areas is wor- thy of note. One-third of the surface of the municipality of Winterthur is built up, one-third is forest and one-third is put to agricultural use. -

Verbandsbefragung 2020 / Enquête Auprès Des Fédérations 2020

Verbandsbefragung 2020 / Enquête auprès des fédérations 2020 Nationaler Sportverband / Fédération nationale sportive Vereine / Mitglieder / Aktivmitglieder / Associations Membres Membre actifs Schweizerischer Fussballverband / Association Suisse de Football 1’396 455’931 276’563 Schweizerischer Turnverband / Fédération Suisse de Gymnastique 2’977 373’198 311’655 Swiss Athletics 438 287’150 36’400 Swiss University Sports / Fédération Suisse du Sport Universitaire 16 220’270 220’000 Swiss Tennis 687 197’378 161’271 Schweizer Alpen-Club / Club Alpin Suisse 111 156’760 156’754 Schweizer Schiesssportverband / Fédération sportive suisse de tir 2’569 135’997 109’825 Swiss-Ski 709 115’140 84’995 Swiss Golf 98 94’079 94’073 Swiss Aquatics 169 75’421 75’000 Swiss Ice Hockey Federation 280 71’663 26’982 Schweizerischer Verband für Pferdesport / Fédération Suisse des Sports Equestres 552 67’474 57’474 Eidgenössischer Schwingerverband / Association fédérale de lutte suisse 168 65’877 5’908 Swiss Volley 471 60’181 36’654 Schweizerischer Firmen- und Freizeitsportverband / Association suisse de sport corporatif et récréation 312 38’023 25’755 Swiss unihockey 396 33’628 33’523 Schweizerischer Handball-Verband / Fédération Suisse de Handball 216 27’967 19’170 Aero-Club der Schweiz / Aéro-Club de Suisse 401 23’435 21’525 Swiss Cycling 392 23’353 7’487 Swiss Sailing 187 20’630 20’579 Swiss Basketball 192 19’338 19’111 Schweizerische Lebensrettungs-Gesellschaft / Société Suisse de Sauvetage 127 19’000 19’000 Schweizerischer Hängegleiter-Verband / Fédération -

Liste Des Spécialités Sportives Classées (État Au 1 Janvier 2021)

Liste des spécialités sportives classées (état au 1 janvier 2021) Fédération Sport Classement Olympique Saison Typ Personne responsable Aéro-Club de Suisse Aéromodélisme 4 Pas olympique Été Sport individuel Müller, Lea Swiss Aquatics Artistic Swimming 3 Olympique Été Sport individuel Rossi, Marianne Swiss Athletics Athlétisme 1 Olympique Été Sport individuel Rossi, Marianne Fédération Suisse des Sociétés d'Aviron Aviron 1 Olympique Été Sport individuel Bonny, Michel swiss badminton Badminton 3 Olympique Été Sport individuel Bonny, Michel Fédération Suisse de Gymnastique Balle au poing 4 Pas olympique Été Sport collectif Bonny, Michel Fédération suisse de baseball et softball Base-ball/softball 5 Olympique Été Sport collectif Müller, Lea Swiss Basketball Basketball à 3 (3x3) 4 Olympique Été Sport d'équipe Peiry, Florian Swiss Basketball Basketball femmes 4 Olympique Été Sport collectif Peiry, Florian Swiss Basketball Basketball hommes 3 Olympique Été Sport collectif Peiry, Florian Association Suisse de Football Beach soccer 4 Pas olympique Été Sport collectif Rossi, Marianne Swiss Volley Beach-volley 1 Olympique Été Sport d'équipe Rossi, Marianne Swiss-Ski Biathlon 2 Olympique Hiver Sport individuel Bonny, Michel Fédération Suisse de Billard Billard 4 Pas olympique Été Sport individuel Müller, Lea Swiss Sliding Bobsleigh 2 Olympique Hiver Sport d'équipe Rossi, Marianne Fédération Suisse de Boccia Boccia 4 Pas olympique Été Sport individuel Müller, Lea Fédération Suisse de Sport-Boules Boules 5 Pas olympique Été Sport individuel Müller, -

Programme Des Matchs Official Program Matchprogramm

1 NEUCHÂTEL 2019 PROGRAMME DES MATCHS OFFICIAL PROGRAM MATCHPROGRAMM #floorball #floorballized #WFCNeuchatel SUH-WCF19-UG-Matchprogramm-a4-en-rz.indd 3 29.11.19 09:24 2 3 NEUCHÂTEL 2019 NEUCHÂTEL 2019 BIENVENUE À NEUCHÂTEL WHERE CHAMPIONS PLAY ™ WELCOME TO NEUCHÂTEL WILLKOMMEN IN NEUENBURG THOMAS BACH PRÉSIDENT CIO IOC PRESIDENT IOC-PRÄSIDENT Chers amis, Dear Friends, Liebe Freunde Le 12ème Championnat du monde With the world’s top floorball athletes Die 12. Unihockey Frauen Weltmeis- d’unihockey féminin, où se ren- coming together in Neuchâtel, the terschaft, bei der sich die weltbesten contrent à Neuchâtel les meilleures 12th Women’s World Floorball Cham- Unihockey-Athletinnen in Neuenburg joueuses d’unihockey du monde, pro- pionships promise to be an excep- treffen, verspricht einen ausserge- met une compétition extraordinaire et tional and intense competition. In the wöhnlichen und intensiven Wettkampf. intense. En accord avec l’esprit olym- Olympic spirit of excellence, respect Im Sinne des olympischen Gedankens pique d’excellence, de respect et de and fair-play, I wish all competitors a von Höchstleistung, Respekt und Fair- fair-play, je souhaite à toutes les par- memorable and successful champion- play wünsche ich allen Teilnehmenden ticipantes un Championnat du monde ship. eine unvergessliche und erfolgreiche inoubliable et réussi. Weltmeisterschaft. My congratulations go to the organ- Mes félicitations vont aux organisa- isers and the International Floorball Meine Glückwünsche richten sich an teurs et à la Fédération Internationale Federation under the leadership of its die Organisatoren und den internatio- d’unihockey (IFF) placée sous la direc- President, Tomas Eriksson. The stage nalen Unihockeyverband IFF unter der tion de son président, Tomas Eriksson. -

MA Sponsoring 2020 Fragenkatalog

MA SPONSORING 2020: Fragenkatalog Themenbereich Im Rahmen der MA Sponsoring werden zahlreiche Themen sowie Sport- und Kulturmarken abgefragt Sport (Interesse, Besuch vor Ort, Bekanntheitsgrad). Darin finden sich alle Zielgruppeninformationen in Bezug auf folgende Plattformen: Sportarten Sportevents Sportligen Badminton Athletissima Lausanne BRACK.CH Challenge League Basketball Badminton Swiss Open Basel LNBA (Nationale Basketball Liga) Beachsoccer BMC Racing Cup National/Swiss League Beachvolleyball Coop Beachtour Nationalliga A (Unihockeyliga A) Biathlon Course de l’ Escalade Genf Nationalliga A (Volleyballliga A) Bob CSIO Schweiz St. Gallen Raiffeisen Super League Classic Cars Swiss Beach Soccer League Curling Davos Nordic Duathlon/Triathlon Eidgenössisches Schwing- und Älplerfest Swiss eSports League E-Sport Eidgenössisches Turnfest Swiss Handball League Eishockey Engadin Skimarathon Swisscom Hero League (E-Sport) Eiskunstlaufen FIS Ski World Cup Adelboden Faustball FIS Ski World Cup Crans-Montana Formel 1 FIS Ski World Cup St. Moritz Sportverbände Formel E FIS Weltcup Skispringen Engelberg ASG (Schweizer Golfverband) Freeride Grand Prix Bern (Ski/Snowboard) FIFA Greifenseelauf Fussball Schweizer Alpen-Club (SAC) Internationales Lauberhornrennen Wengen Golf Schweizerischer Schiesssportverband Ironman Zurich Switzerland Handball Schweizerischer Turnverband LAAX Open Inlineskating SFV (Schweizer Fussballverband) Kampfsport/Boxen Omega European Masters SVPS (Schweizerischer Verband -

Statistik 2014 – Nutzergruppe: 4 Kurse Und Lager

Eidgenössisches Departement für Verteidigung, Bevölkerungsschutz und Sport Jugend- und Erwachsenensport Nutzergruppe: 4 Jugendausbildung 2014 Kurse und Lager Zielgruppe: Alle Verband Kurse und Lager Angebote Knaben Mädchen Total Eingesetzte Leitende Coach-entschädigung Kurs-Beitrag Total Auszahlungen Berufsverband für Gesundheit und Bewegung 1 1 3 42 45 2 107 1'064 1'171 Eidg. Nationalturner-Verband 4 4 153 37 190 35 803 8'011 8'814 Eidg. Schwingerverband 2 2 86 0 86 16 293 2'919 3'212 Gemeinden 294 212 9'094 5'351 14'445 1'698 40'007 444'127 484'134 Kantonale Ämter für J+S 163 86 4'076 2'846 6'922 1'013 296 335'868 336'164 Naturfreunde Schweiz 3 3 43 32 75 19 382 18'109 18'491 Ohne Dachverband (Admin.) 1 1 5 9 14 3 75 3'605 3'680 PLUSPORT Behindertensport Schweiz 1 1 11 9 20 9 83 829 912 SATUS Schweiz 1 1 31 22 53 8 242 2'417 2'659 SVKT Frauensportverband 2 1 0 51 51 7 234 2'327 2'561 Schweiz Verband für Sport-Freizeit-Verkehr 1 1 6 25 31 3 142 1'414 1'556 Schweiz. Fussballverband 12 12 732 112 844 101 2'817 28'108 30'925 Schweiz. Handball Verband 1 1 29 8 37 6 169 1'688 1'857 Schweiz. Judo- und Ju-Jitsu-Verband 10 8 373 122 495 71 1'922 19'200 21'122 Schweiz. Kanu-Verband 6 1 74 29 103 26 527 5'246 5'773 Schweiz. Lebensrettungs-Gesellschaft 1 1 27 70 97 11 357 3'565 3'922 Schweiz. -

Liste Der Endbegünstigten (Stand: 31. März 2021)

Liste der Endbegünstigten (Stand: 31. März 2021) Ausbezahlte Summe Name des Endempfängers Verband Art der Organisation 2020 in CHF Kanton Aargau 3’723’931 Aarauer Altstadtlauf Swiss Athletics Anlässe des Breiten- und Leistungssports in der Schweiz Aargau Kunstturnvereinigungen Kutu M Schweizerischer Turnverband Infrastruktur Aargauer Schwingerverband Eigenössicher Schwingerverband Regional-/Kantonalverband Aargauischer Fussballverband AFV Schweizerischer Fussballverband Regional-/Kantonalverband Aargauischer Leichtathletik-Verband ALV Swiss Athletics Regional-/Kantonalverband Aargauischer Tennisverband, Dottikon, Swiss Tennis Regional-/Kantonalverband Aargauischer Tennisverband, Swiss Tennis Vereine Aarsports GmbH Swiss Squash Infrastruktur Aarsports GmbH Swiss Badminton Infrastruktur Ammerswil TV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Argovia Pirates American Football Club Schweizerischer American Football Verband Vereine Argovia Stars Swiss Ice Hockey Federation Vereine Argovia Synchro Swiss Aquatics Vereine Baden Basket 54 Swiss Basketball Vereine Badminton Club Speuz (Erlinsbach) Swiss Badminton Vereine Badmintonclub Aarau Swiss Badminton Vereine Besenbüren TV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Biberstein STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Billard-Center Kiss-Shot Staufen Schweizerischer Billard Verband Infrastruktur Boswil FTV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Bottenwil TV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Box Club Aarau Swiss Boxing Vereine Bözberg FTV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Bözberg MR STV -

Verletzungen Im Unihockey

Verletzungen im Unihockey Eine Fragebogenerhebung bei Schweizer Nationalliga A Unihockey Spielern Bachelor-Thesis Jonas Engel Matrikel-Nr. 10-109-692 Moritz Kälin Matrikel-Nr. 14-257-042 Berner Fachhochschule Fachbereich Gesundheit Bachelor oF Science Physiotherapie, PHY14 ReFerent Dr. Slavko Rogan, MSc, MSc, M.A. Bern, 31.08.2017 Verletzungen im Unihockey DANKSAGUNG Ein herzlicher Dank gilt dem ReFerenten Slavko Rogan Für die Betreuung im Entstehungsprozess dieser Bachelorarbeit und dafür, dass er zu jedem Zeitpunkt erreichbar war. Zudem bedanken wir uns beim schweizerischen Unihockeyverband Swiss Unihockey zur Kontaktvermittlung der Clubverantwortlichen. Diese Unterstützung erleichterte die Probandensuche erheblich. Ein grosser Dank geht an die Trainer der FünF angeschrieben Berner Nationalliga A Ver- treter, die eine reibungslose Fragebogenerhebung so kurz vor den Ausscheidungs- runden ermöglichten. Weiter möchten wir uns bei den Spielern bedanken, die sich Für unsere Untersuchung zur VerFügung gestellt haben und die Fragebögen vorbehaltlos ausfüllten. Ein besonderes Dankeschön geht an Pascal Karrer und Rea Hermann für das zeit- aufwändige Gegenlesen. 2 Verletzungen im Unihockey INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Danksagung 2 Abstract 5 1 Einleitung und Zielstellung 6 2 Grundlagen 8 2.1 Unihockey 8 2.1.1 Unihockey in der Schweiz 8 2.1.2 Spielbetrieb 9 2.1.3 Charakteristik der Sportart Unihockey 10 2.1.4 Schutzausrüstung 11 2.2 Verletzungen 11 2.2.1 DeFinition 11 2.2.2 Verletzungshergang 12 2.2.3 Psychologische Faktoren 14 2.2.4 Sportverletzungen in -

Financial Report 31.12.2013 Balance Sheet 31.12.2013 Appendix 2

Financial Report 31.12.2013 Balance sheet 31.12.2013 Appendix 2 COSTS GA Budget Outcome Compared Outcome ASSETS Cost Centre 19.08.2013 19.08.2012 /Ann.budget Current assets 01.01.2013 19.08.2013 10 Central activities 15000 10758,72 8374,85 4241 Cash 0,00 0,00 11 Office 643000 404676,49 320396,78 238324 Credit Suisse 559200-11 465926,46 259380,89 12 CB 50500 37239,38 33810,47 13261 13 ExCo 10000 6993,40 2881,87 3007 Receivables 14 GA/AM 9500 0,00 0,00 9500 Claims 2010 122901,09 120901,09 15 External meetings 22300 8700,37 17194,36 13600 Claims 2011 87955,07 70625,26 16 IOC 50 Road Map 4000 2442,87 15642,25 1557 Claims 2012 303103,52 130370,65 17 Parafloorball 9000 2498,18 0,00 6502 Claims 2013 0,00 114821,00 18 Equality Function 7500 0,00 0,00 7500 Deferr expenses and accr income 0,00 0,00 19 Athletes Commission 10000 0,00 0,00 10000 Receivables from rel.parties 7089,36 16844,90 20 WFC 192000 20282,12 28130,24 171718 Total assets 986975,50 712943,79 21 U19 WFC 28500 24621,64 22994,78 3878 22 EFC 40500 0,00 225,35 40500 LIABILITIES AND EQUITY 23 Champions Cup 80000 6262,67 624,06 73737 25 WUC 0 0,00 1099,43 0 Current liabilities 29 Anti-Doping 27000 8107,11 14183,30 18893 Accr expenses and deferr income -373200,00 -232000,00 40 RACC 27000 0,00 14490,94 27000 Other current liabilities -3356,98 -4556,98 50 RC 34000 16535,71 17506,21 17464 Transfers to reserves -280487,97 -540,00 60 Development 48000 20840,10 22362,70 27160 Development reserves 0,00 0,00 70 Material* 110000 8607,67 8337,10 101392 Development Board reserves 2011 -14832,48 -14832,48 -

Causes, Forms and Consequences of Professionalization in Swiss National Sport Federations

Causes, forms and consequences of professionalization in Swiss national sport federations Inauguraldissertation der Philosophisch-humanwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Bern zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde vorgelegt von Kaisa Ruoranen aus Finnland Original document saved on the web server of the University Library of Bern. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No derivative works 2.5 Switzerland license. To see the license go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/deed.en or write to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA. Von der Philosophisch-humanwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Bern auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Siegfried Nagel und Prof. Dr. Fabien Ohl angenommen. Bern, 12. Dezember 2018 Die Dekanin: Prof. Dr. Tina Hascher Die Disputation: 5. November 2018, Bern Der Vorsitz: Prof. Dr. Roland Seiler Copyright Notice This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial-No derivative works 2.5 Switzerland. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/deed.en You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work. Under the following conditions: Attribution. You must give the original author credit. Non-Commercial. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No derivative works. You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Nothing in this license impairs or restricts the author’s moral rights according to Swiss law. -

Det Vises Til Sak 4

COSTS Congress 2000 CB Revised Diff. Cong. Preliminary Diff. Budget Budget Rev.budget Outcome Per.budget Rev.budget Cost Centre 2002 2002 31.12.02 31.12.02 Outcome 10 Central activities 9500 25600 16100 15262 25600 10338 11 Office 135000 169000 34000 133046 169000 35954 12 CB 46900 30000 -16900 36061 30000 -6061 13 Congress 3000 2000 -1000 7329 2000 -5329 14 President's Meeting 0 0 0 0 0 0 15 External meetings 0 0 0 9897 0 -9897 40 RACC 13000 15800 2800 7807 15800 7993 WFC 8200 0 -8200 0 0 0 1 U19 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 EuroCup 16500 0 -16500 0 0 0 1 50 RC 22100 18100 -4000 18182 18100 -82 60 EDC 25500 16300 -9200 6471 16300 9829 70 MC 99200 160000 60800 207949 160000 -47949 80 MIC 20300 15900 -4400 5173 15900 10727 90 SAG 4400 2700 -1700 0 2700 2700 91 AC 3200 2800 -400 1042 2800 1758 92 DC 3200 2800 -400 1584 2800 1216 TOTAL CHF 410000 461000 51000 449802,14 461000,00 11198 INCOME Account 3011 Transfers 20000 20000 0 22600 20000 -2600 3012 Participation fees 37000 42000 5000 56000 42000 -14000 3013 Organizers fee 70000 60000 -10000 55000 60000 5000 3210 Membership fees 40000 36000 -4000 36166 36000 -166 3219 Fines 0 0 0 16500 0 -16500 3250 Sponsors & advertisements 100000 100000 0 45000 100000 55000 3510 Sales 2000 0 -2000 0 0 0 3860 Material approval income 140000 210000 70000 237985 210000 -27985 3899 Other incomes 1000 600 -400 349 600 251 8020 Interest 0 400 400 332 400 68 8080 Exchange rate gains 0 0 0 36 0 -36 TOTAL CHF 410000 469000 59000 469968,29 469000,00 -968 Estimated Result CHF 0 8000 8000 20166,15 8000,00 -12166 Notes: 1) WFC, U19 WFC and EuroCup are now included in the Committees.