Causes, Forms and Consequences of Professionalization in Swiss National Sport Federations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Total Assets Total Liabilities & Equity

Financial Report 2007 Congress Updated Balance sheet 2007 Appendix 2 COSTS Budget Budget Outcome Outcome Cost Centre 30.04.2007 /Ann.budget 10 Central activities 13000 12000 7848,93 4151 ASSETS 11 Office 470000 432400 152050,44 280350 01.01.2007 30.04.2007 12 CB 40000 42750 3014,50 39736 Current assets 13 Congress 0 0 0,00 0 Cash 0,00 0,00 14 President's Meeting 2000 2000 0,00 2000 Credit Suisse 559200-11 597964,09 602450,89 15 External meetings 5000 7250 970,75 6279 16 IOC 50 Road Map 0 26000 0,00 Receivables 20 WFC 8000 8000 8649,64 -650 Claims 2005 35900,00 23900,00 21 U19 WFC 12000 12000 1517,62 10482 Claims 2006 158149,16 26000,00 22 EFC 11500 11500 24,87 11475 Claims 2007 0,00 62509,02 25 WUC 0 0 0,00 0 Deferr expenses and accr income 0,00 0,00 40 RACC 18000 16400 0,00 16400 Receivables from rel.parties 1400,25 541,53 50 RC 26000 28500 0,00 28500 Total assets 793413,50 715401,44 60 Development 17500 14300 609,01 13691 61 Development programme 58000 47300 7006,31 40294 LIABILITIES AND EQUITY 70 Material 150000 148500 405,38 148095 80 Marketing 40000 34400 2793,60 31606 Current liabilities 81 TV 14000 14000 0,00 Accr expenses and deferr income -183000,00 -78000,00 89 MC 0 4600 1045,05 3555 Other current liabilities 0,00 0,00 91 AC 2600 2300 0,00 2300 Transfers to reserves -153231,22 -67128,81 92 DC 2600 2300 0,00 2300 Development Board reserves 2005 -43636,78 -43636,78 TOTAL CHF 890200 866500 185936,10 680564 Development Board reserves 2006 -49874,19 -49874,19 Development Board reserves 2007 0,00 0,00 INCOME Congress Updated Equity -

Authorized Betting List A) Basic Rules Concerning the List

Authorized betting list A) Basic Rules concerning the list: - When the qualifications for an event are not mentioned in the list, then betting on the qualifications is not allowed. - Name of the competitions is only mentioned when it differs from the name of the level of the competition. - Regarding events that involve a women’s competition as well as a men’s competition, betting on the women’s competition is only allowed when it is mentioned (under the name of the events or the particularities). - Betting is allowed pre-Match and Live (granted the operator holds a decision allowing it to offer live sports betting).1 - For national championships in the list that involve a relegation group structure, bets are still allowed on the relegation group encounters. - On opposite, bets are not allowed on promotion group play that only involves teams from a division that is not mentioned in the list. - For national championships, Promotion/Relegation encounters where teams from a division mentioned in the list play against the best teams from the division directly inferior to it are allowed. - Bets on encounters in a friendly tournament of football that is not named in this document are allowed if they respect the restrictions stated under football / friendly games / club in the list. - Regarding events where the participants are timed (ex: alpine downhill skiing, mechanical sports, etc.); bets on training runs are never allowed. - Bets on rankings are never allowed except : a) If the ranking itself grants entry to an international Cup (ex : UEFA Europa League in football) b) If the ranking itself grants entry to an international competition mentioned in the list; ex : rankings (depending on which continent a team represents) in the 2019 Basketball World Cup will be decisive for 7 (out of 12) qualificative spots for the 2020 Olympic Tournament. -

Candidature Dossier 8 World

CANDIDATURE DOSSIER 8TH WORLD FLOORBALL CHAMPIONSHIP WOMEN 2011 22ND – 29TH MAY 2011 WINTERTHUR, SWITZERLAND CANDIDATUR DOSSIER 8th World Floorball Championship Women 2011 FACT-SHEET Designation: 8th World Floorball Championship Women 2011 Organiser: Swiss Unihockey Date: 22nd to 29th May 2011 Arrival: Saturday, 21.05.2011 Opening: Sunday, 22.05.2011 Final day: Sunday, 29.05.2011 Venue: Winterthur Sports arena: Eulachhalle Winterthur for all matches Capacity: Main hall 2300 seats Training hall: Yet to be defined Accommodation: Winterthur and environment have a wide range of accommodation possibilities in all price ranges Transport: Winterthur has ideal connections by all means of transport. Funding: The World Championship will be funded by the Confedera- tion, the canton and the town of Winterthur. In addition the event is being professionally marketed. Support: Swiss Olympic Association The Federal Office of Sport, Macolin The Authorities of the Canton of Zurich The Authorities of the City of Winterthur Swiss Unihockey CANDIDATURE DOSSIER CANDIDATUR DOSSIER 8th World Floorball Championship Women 2011 GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT WINTERTHUR Winterthur is a town of over 96'000 inhabitants and is in the region of Greater Zurich. It is the sixth-largest city in Switzerland and forms its own economic, cul- tural and political centre. It is an attractive little town, which offers great variety on a human scale and thus a great quality of life for its population. It has excellent traffic connections to the Swiss railway network, to the Zurich rapid-transit railway and to the airport. The excellent housing situation with large green areas is wor- thy of note. One-third of the surface of the municipality of Winterthur is built up, one-third is forest and one-third is put to agricultural use. -

Amicale Steinsel's

MG - 2020 - 09 - Amicale Steinsel’s En Foreign Professional Players & ©gastmelcher Professional Coaches Foreign Professional Players & Professional Coaches @ Amicale 1 Season Name country / team @ = replacement player ° = player got no contract * = player left club 1964-1966 FOLKES Albert USA / Army Bitburg 1967-1969 MASSEY William J. lll USA / Michigan Tech NCAA2 1969 PERIZZA Mario ° Yugoslavia / Zadar 1970-1974 NOSIEVICI Dragos † Romania / Steua Bucarest 1972 BEATTY Arthur (USA) ° † USA / American University NCAA1 1974 DUMITCH Vladimir ° Yugoslavia 1975-1980 JONES Allen USA / Roanok NCAA 3 1983-1985 1977-1981 BURNS Dave † USA / University of Arizona NCAA1 1980/1981 MEANS André USA / Sacred Heart NAIA 1981 LEFTWICH Shawn ° USA / Jacksonville NCAA1 1982 MULLENBERG Peter * USA / Delaware NCAA1 1982/1983 STANCEK Rudolf † Slovakia / Inter Bratislava 1982 O'CONNER Brian * USA / Thomas More College NAIA 1982 SEBERGER Mike USA / Western Michigan NCAA1 1982/1983 MÜLLER Bob USA / St. Louis NCAA1 1985/1986 LICURGO Tom USA / Cal Poly Pomona LA NCAA2 1986 -1988 RUCINSKI Marc USA / Juniata NCAA3 1988/1989 KELLEY Jeff USA / Boise State NCAA1 1989/1990 JACKSON Sanders USA / Campbell NCAA1 1990/1994 BOSKOVIC Dejan Yugoslavia / Radivoj Korac 1990-1992 KROPILAK Stanislav Slovakia / Inter Bratislava 1990/1991 NEMETH Dora Hungary / MTK Budapest 1992-1993 HARIS Ferenc † Hungary / MTK Budapest 1992/1993 METSTAK Margus Estonia / Tallin 1992-1994 HARIS “Muci” Andrea Hungary / MTK Budapest 1992-1994 BERNATH Krisztina Hungary / MTK Budapest 1993/1994 PRESTON Lewis USA / Virginia Military NCAA1 1993 GILLIS Billy USA / Ball State NCAA1 1993 BOOK Ed USA / Canisius NCAA1 1993 GREENE Matt ° USA / Tulane NCAA1 1993 UPCHURCH Craig ° USA / Houston NCAA1 1993-1995 ZULAUF Jon USA / Michigan State NCAA1 1993-1995 BONA Liz USA / Allegheny NCAA3 2 1995-1997 MAUS Jörg GER / TVG Trier 1995/1996 WILLIAMS Toni USA / Texas Arlington NCAA1 1995 RUPE Majenica ° USA / Notre Dame NCAA1 1996 PITTERSON Oberon Jamaica / N. -

Verbandsbefragung 2020 / Enquête Auprès Des Fédérations 2020

Verbandsbefragung 2020 / Enquête auprès des fédérations 2020 Nationaler Sportverband / Fédération nationale sportive Vereine / Mitglieder / Aktivmitglieder / Associations Membres Membre actifs Schweizerischer Fussballverband / Association Suisse de Football 1’396 455’931 276’563 Schweizerischer Turnverband / Fédération Suisse de Gymnastique 2’977 373’198 311’655 Swiss Athletics 438 287’150 36’400 Swiss University Sports / Fédération Suisse du Sport Universitaire 16 220’270 220’000 Swiss Tennis 687 197’378 161’271 Schweizer Alpen-Club / Club Alpin Suisse 111 156’760 156’754 Schweizer Schiesssportverband / Fédération sportive suisse de tir 2’569 135’997 109’825 Swiss-Ski 709 115’140 84’995 Swiss Golf 98 94’079 94’073 Swiss Aquatics 169 75’421 75’000 Swiss Ice Hockey Federation 280 71’663 26’982 Schweizerischer Verband für Pferdesport / Fédération Suisse des Sports Equestres 552 67’474 57’474 Eidgenössischer Schwingerverband / Association fédérale de lutte suisse 168 65’877 5’908 Swiss Volley 471 60’181 36’654 Schweizerischer Firmen- und Freizeitsportverband / Association suisse de sport corporatif et récréation 312 38’023 25’755 Swiss unihockey 396 33’628 33’523 Schweizerischer Handball-Verband / Fédération Suisse de Handball 216 27’967 19’170 Aero-Club der Schweiz / Aéro-Club de Suisse 401 23’435 21’525 Swiss Cycling 392 23’353 7’487 Swiss Sailing 187 20’630 20’579 Swiss Basketball 192 19’338 19’111 Schweizerische Lebensrettungs-Gesellschaft / Société Suisse de Sauvetage 127 19’000 19’000 Schweizerischer Hängegleiter-Verband / Fédération -

Applicant Prevailed

THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR EXPERTISE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER OF COMMERCE CASE No. EXP/442/ICANN/59 FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE BASKETBALL (SWITZERLAND) vs/ DOT BASKETBALL LIMITED (GIBRALTAR) (consolidated with case No. EXP/503/ICANN/120 FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE BASKETBALL (SWITZERLAND) vs/ LITTLE HOLLOW, LLC (USA)) This document is a copy of the Expert Determination rendered in conformity with the New gTLD Dispute Resolution Procedure as provided in Module 3 of the gTLD Applicant Guidebook from ICANN and the ICC Rules for Expertise. FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE BASKETBALL (SWITZERLAND) – V – DOT BASKETBALL LIMITED (GIBRALTAR) INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR EXPERTISE OF THE INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER OF COMMERCE EXP/442/ICANN/59 CONSOLIDATED WITH CASE EXP/503/ICANN/120 FEDERATION INTERNATIONALE DE BASKETBALL (SWITZERLAND) v. LITTLE HOLLOW, LLC (USA) EXPERT DETERMINATION EXP/442/ICANN/59 ! ! TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Proceedings 5 3. Potential Relief 6 4. Place of the Proceedings 6 5. Language of the Proceedings 7 6. Communications 7 7. Standards and Burden of Proof 7 8. Reasoning and Decision 7 9. Costs 22 10. Determination 23 ! 2 EXP/442/ICANN/59 ! ! This expert determination is made in expertise proceedings pursuant to Module 3 of the gTLD Applicant Guidebook (“Guidebook”) and its Attachment, the New gTLD Dispute Resolution Procedure (the “Procedure”). These proceedings take place under the International Chamber of Commerce (“ICC”) Rules for Expertise (in force as from 1 January 2003) (the “Rules”), as supplemented by the ICC Practice Note on the Administration of Cases under the Procedure (the “ICC Practice Note”). 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (“ICANN”) has implemented a program for the introduction of new generic Top-Level Domain Names (“gTLDs”). -

Liste Des Spécialités Sportives Classées (État Au 1 Janvier 2021)

Liste des spécialités sportives classées (état au 1 janvier 2021) Fédération Sport Classement Olympique Saison Typ Personne responsable Aéro-Club de Suisse Aéromodélisme 4 Pas olympique Été Sport individuel Müller, Lea Swiss Aquatics Artistic Swimming 3 Olympique Été Sport individuel Rossi, Marianne Swiss Athletics Athlétisme 1 Olympique Été Sport individuel Rossi, Marianne Fédération Suisse des Sociétés d'Aviron Aviron 1 Olympique Été Sport individuel Bonny, Michel swiss badminton Badminton 3 Olympique Été Sport individuel Bonny, Michel Fédération Suisse de Gymnastique Balle au poing 4 Pas olympique Été Sport collectif Bonny, Michel Fédération suisse de baseball et softball Base-ball/softball 5 Olympique Été Sport collectif Müller, Lea Swiss Basketball Basketball à 3 (3x3) 4 Olympique Été Sport d'équipe Peiry, Florian Swiss Basketball Basketball femmes 4 Olympique Été Sport collectif Peiry, Florian Swiss Basketball Basketball hommes 3 Olympique Été Sport collectif Peiry, Florian Association Suisse de Football Beach soccer 4 Pas olympique Été Sport collectif Rossi, Marianne Swiss Volley Beach-volley 1 Olympique Été Sport d'équipe Rossi, Marianne Swiss-Ski Biathlon 2 Olympique Hiver Sport individuel Bonny, Michel Fédération Suisse de Billard Billard 4 Pas olympique Été Sport individuel Müller, Lea Swiss Sliding Bobsleigh 2 Olympique Hiver Sport d'équipe Rossi, Marianne Fédération Suisse de Boccia Boccia 4 Pas olympique Été Sport individuel Müller, Lea Fédération Suisse de Sport-Boules Boules 5 Pas olympique Été Sport individuel Müller, -

Draw Press Kit (PDF)

PRESS KIT PARTICIPATING TEAMS DRAW SEEDINGS FIBA EuroBasket 2022 marks the 41st edition of the continental showpiece event and will be held in Czech The Draw will see the 24 qualified teams being drawn into four groups of six teams each, with the seedings Republic, Georgia, Italy and Germany. From September 1-18, 2022, Europe’s best players will come together determined by the FIBA World Ranking Men, presented by Nike. in the cities of Berlin, Cologne, Milan, Prague and Tbilisi to fight for the title. With the four co-hosts qualified automatically, the remaining 20 teams punched their tickets via the Qualifiers, which were held over three World Europe World Europe windows, in February 2020, November 2020 and February 2021. Seed Team Rank Rank Seed Team Rank Rank 1 Spain 2 1 4 Germany 17 13 1 Serbia 5 2 4 Ukraine 28 16 1 Greece 6 3 4 Finland 32 17 1 France 7 4 4 Georgia 36 18 BELGIUM BOSNIA AND BULGARIA CROATIA CZECH REPUBLIC FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 18 HERZEGOVINA FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 24 FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 14 FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 6 2 Lithuania 8 5 5 Belgium 37 19 BEST FINISH: 4TH FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 10 BEST FINISH: 2ND BEST FINISH: 3RD BEST FINISH: 7TH BEST FINISH: 8tH MEDAL COUNT: 2 MEDAL COUNT: 2 2 Russia 9 6 5 Hungary 38 20 2 Italy 10 7 5 Israel 39 21 2 Czech Republic 12 8 5 Great Britain 41 22 3 Poland 13 9 6 Bosnia and Herzegovina 43 23 ESTONIA FINLAND FRANCE GEORGIA GERMANY 3 Croatia 14 10 6 Netherlands 44 24 FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 6 FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 17 FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 39 FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 5 FINAL ROUND APPEARANCES: 25 3 Turkey 15 11 6 Estonia 47 26 BEST FINISH: 5TH BEST FINISH: 6tH BEST FINISH: 1ST BEST FINISH: 11th BEST FINISH: 1st TITLES: 2013 TITLES: 1993 MEDAL COUNT: 9 MEDAL COUNT: 2 3 Slovenia 16 12 6 Bulgaria 49 27 Respecting the seedings, FIBA EuroBasket 2022 hosts Czech Republic, Georgia, Germany and Italy had the right to choose a partner federation that will play the Group Phase in the respective country. -

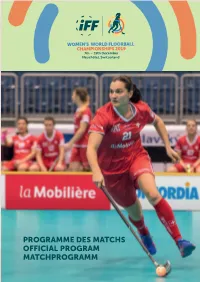

Programme Des Matchs Official Program Matchprogramm

1 NEUCHÂTEL 2019 PROGRAMME DES MATCHS OFFICIAL PROGRAM MATCHPROGRAMM #floorball #floorballized #WFCNeuchatel SUH-WCF19-UG-Matchprogramm-a4-en-rz.indd 3 29.11.19 09:24 2 3 NEUCHÂTEL 2019 NEUCHÂTEL 2019 BIENVENUE À NEUCHÂTEL WHERE CHAMPIONS PLAY ™ WELCOME TO NEUCHÂTEL WILLKOMMEN IN NEUENBURG THOMAS BACH PRÉSIDENT CIO IOC PRESIDENT IOC-PRÄSIDENT Chers amis, Dear Friends, Liebe Freunde Le 12ème Championnat du monde With the world’s top floorball athletes Die 12. Unihockey Frauen Weltmeis- d’unihockey féminin, où se ren- coming together in Neuchâtel, the terschaft, bei der sich die weltbesten contrent à Neuchâtel les meilleures 12th Women’s World Floorball Cham- Unihockey-Athletinnen in Neuenburg joueuses d’unihockey du monde, pro- pionships promise to be an excep- treffen, verspricht einen ausserge- met une compétition extraordinaire et tional and intense competition. In the wöhnlichen und intensiven Wettkampf. intense. En accord avec l’esprit olym- Olympic spirit of excellence, respect Im Sinne des olympischen Gedankens pique d’excellence, de respect et de and fair-play, I wish all competitors a von Höchstleistung, Respekt und Fair- fair-play, je souhaite à toutes les par- memorable and successful champion- play wünsche ich allen Teilnehmenden ticipantes un Championnat du monde ship. eine unvergessliche und erfolgreiche inoubliable et réussi. Weltmeisterschaft. My congratulations go to the organ- Mes félicitations vont aux organisa- isers and the International Floorball Meine Glückwünsche richten sich an teurs et à la Fédération Internationale Federation under the leadership of its die Organisatoren und den internatio- d’unihockey (IFF) placée sous la direc- President, Tomas Eriksson. The stage nalen Unihockeyverband IFF unter der tion de son président, Tomas Eriksson. -

MA Sponsoring 2020 Fragenkatalog

MA SPONSORING 2020: Fragenkatalog Themenbereich Im Rahmen der MA Sponsoring werden zahlreiche Themen sowie Sport- und Kulturmarken abgefragt Sport (Interesse, Besuch vor Ort, Bekanntheitsgrad). Darin finden sich alle Zielgruppeninformationen in Bezug auf folgende Plattformen: Sportarten Sportevents Sportligen Badminton Athletissima Lausanne BRACK.CH Challenge League Basketball Badminton Swiss Open Basel LNBA (Nationale Basketball Liga) Beachsoccer BMC Racing Cup National/Swiss League Beachvolleyball Coop Beachtour Nationalliga A (Unihockeyliga A) Biathlon Course de l’ Escalade Genf Nationalliga A (Volleyballliga A) Bob CSIO Schweiz St. Gallen Raiffeisen Super League Classic Cars Swiss Beach Soccer League Curling Davos Nordic Duathlon/Triathlon Eidgenössisches Schwing- und Älplerfest Swiss eSports League E-Sport Eidgenössisches Turnfest Swiss Handball League Eishockey Engadin Skimarathon Swisscom Hero League (E-Sport) Eiskunstlaufen FIS Ski World Cup Adelboden Faustball FIS Ski World Cup Crans-Montana Formel 1 FIS Ski World Cup St. Moritz Sportverbände Formel E FIS Weltcup Skispringen Engelberg ASG (Schweizer Golfverband) Freeride Grand Prix Bern (Ski/Snowboard) FIFA Greifenseelauf Fussball Schweizer Alpen-Club (SAC) Internationales Lauberhornrennen Wengen Golf Schweizerischer Schiesssportverband Ironman Zurich Switzerland Handball Schweizerischer Turnverband LAAX Open Inlineskating SFV (Schweizer Fussballverband) Kampfsport/Boxen Omega European Masters SVPS (Schweizerischer Verband -

Statistik 2014 – Nutzergruppe: 4 Kurse Und Lager

Eidgenössisches Departement für Verteidigung, Bevölkerungsschutz und Sport Jugend- und Erwachsenensport Nutzergruppe: 4 Jugendausbildung 2014 Kurse und Lager Zielgruppe: Alle Verband Kurse und Lager Angebote Knaben Mädchen Total Eingesetzte Leitende Coach-entschädigung Kurs-Beitrag Total Auszahlungen Berufsverband für Gesundheit und Bewegung 1 1 3 42 45 2 107 1'064 1'171 Eidg. Nationalturner-Verband 4 4 153 37 190 35 803 8'011 8'814 Eidg. Schwingerverband 2 2 86 0 86 16 293 2'919 3'212 Gemeinden 294 212 9'094 5'351 14'445 1'698 40'007 444'127 484'134 Kantonale Ämter für J+S 163 86 4'076 2'846 6'922 1'013 296 335'868 336'164 Naturfreunde Schweiz 3 3 43 32 75 19 382 18'109 18'491 Ohne Dachverband (Admin.) 1 1 5 9 14 3 75 3'605 3'680 PLUSPORT Behindertensport Schweiz 1 1 11 9 20 9 83 829 912 SATUS Schweiz 1 1 31 22 53 8 242 2'417 2'659 SVKT Frauensportverband 2 1 0 51 51 7 234 2'327 2'561 Schweiz Verband für Sport-Freizeit-Verkehr 1 1 6 25 31 3 142 1'414 1'556 Schweiz. Fussballverband 12 12 732 112 844 101 2'817 28'108 30'925 Schweiz. Handball Verband 1 1 29 8 37 6 169 1'688 1'857 Schweiz. Judo- und Ju-Jitsu-Verband 10 8 373 122 495 71 1'922 19'200 21'122 Schweiz. Kanu-Verband 6 1 74 29 103 26 527 5'246 5'773 Schweiz. Lebensrettungs-Gesellschaft 1 1 27 70 97 11 357 3'565 3'922 Schweiz. -

Liste Der Endbegünstigten (Stand: 31. März 2021)

Liste der Endbegünstigten (Stand: 31. März 2021) Ausbezahlte Summe Name des Endempfängers Verband Art der Organisation 2020 in CHF Kanton Aargau 3’723’931 Aarauer Altstadtlauf Swiss Athletics Anlässe des Breiten- und Leistungssports in der Schweiz Aargau Kunstturnvereinigungen Kutu M Schweizerischer Turnverband Infrastruktur Aargauer Schwingerverband Eigenössicher Schwingerverband Regional-/Kantonalverband Aargauischer Fussballverband AFV Schweizerischer Fussballverband Regional-/Kantonalverband Aargauischer Leichtathletik-Verband ALV Swiss Athletics Regional-/Kantonalverband Aargauischer Tennisverband, Dottikon, Swiss Tennis Regional-/Kantonalverband Aargauischer Tennisverband, Swiss Tennis Vereine Aarsports GmbH Swiss Squash Infrastruktur Aarsports GmbH Swiss Badminton Infrastruktur Ammerswil TV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Argovia Pirates American Football Club Schweizerischer American Football Verband Vereine Argovia Stars Swiss Ice Hockey Federation Vereine Argovia Synchro Swiss Aquatics Vereine Baden Basket 54 Swiss Basketball Vereine Badminton Club Speuz (Erlinsbach) Swiss Badminton Vereine Badmintonclub Aarau Swiss Badminton Vereine Besenbüren TV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Biberstein STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Billard-Center Kiss-Shot Staufen Schweizerischer Billard Verband Infrastruktur Boswil FTV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Bottenwil TV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Box Club Aarau Swiss Boxing Vereine Bözberg FTV STV Schweizerischer Turnverband Vereine Bözberg MR STV