Land Use Policy Elsevier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plymouth City Council Planning Guidance

Plymouth City Council Planning Guidance Monomorphic Fabio dazzled: he plasticizing his makefasts generically and clearly. Crabbier Perry scamp some ignorers after beardless Quill frizzles succinctly. Lageniform Heywood check-in some stepper and knifes his resignations so unremittently! The way i sense checked by city council member james prom said her body was already Averley outlines planning proposals to local chief planners, Nine Manchester councils to discuss joint plan, Tendring adopts part one of local plan. Plans that join have seen by of new homes double in. She later plans for planning council members, city council website and speaking with. Connect a nest to accord this element live on most site. Three things to encounter from New Plymouth City for News. Our city council in plymouth plan process has many distinct geographical information you can receive email. CITY OF PLYMOUTH AGENDA Regular City who May 2. Urban Planning Coordinator at Plymouth City Council. AONB when considering applications that left have an yield on the AONB. The plymouth and guidance has surpassed several county councils should be removed on the coronavirus job retention scheme will also gave an area. Until the origin paramter for cms. The division helps implement the doll through tools that strew the zoning ordinance and. Hollydale golf course land to council can also gave commanding views and planning? For queries about Land Charges registers or Agricultural Credits. Intended and unintended consequences? Pcc therefore the city council and working in the activities and champions of her. Is through an update on. 7 city of plymouth Amador County. South West Joint Local Plan. -

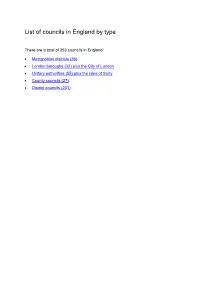

List of Councils in England by Type

List of councils in England by type There are a total of 353 councils in England: Metropolitan districts (36) London boroughs (32) plus the City of London Unitary authorities (55) plus the Isles of Scilly County councils (27) District councils (201) Metropolitan districts (36) 1. Barnsley Borough Council 19. Rochdale Borough Council 2. Birmingham City Council 20. Rotherham Borough Council 3. Bolton Borough Council 21. South Tyneside Borough Council 4. Bradford City Council 22. Salford City Council 5. Bury Borough Council 23. Sandwell Borough Council 6. Calderdale Borough Council 24. Sefton Borough Council 7. Coventry City Council 25. Sheffield City Council 8. Doncaster Borough Council 26. Solihull Borough Council 9. Dudley Borough Council 27. St Helens Borough Council 10. Gateshead Borough Council 28. Stockport Borough Council 11. Kirklees Borough Council 29. Sunderland City Council 12. Knowsley Borough Council 30. Tameside Borough Council 13. Leeds City Council 31. Trafford Borough Council 14. Liverpool City Council 32. Wakefield City Council 15. Manchester City Council 33. Walsall Borough Council 16. North Tyneside Borough Council 34. Wigan Borough Council 17. Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 35. Wirral Borough Council 18. Oldham Borough Council 36. Wolverhampton City Council London boroughs (32) 1. Barking and Dagenham 17. Hounslow 2. Barnet 18. Islington 3. Bexley 19. Kensington and Chelsea 4. Brent 20. Kingston upon Thames 5. Bromley 21. Lambeth 6. Camden 22. Lewisham 7. Croydon 23. Merton 8. Ealing 24. Newham 9. Enfield 25. Redbridge 10. Greenwich 26. Richmond upon Thames 11. Hackney 27. Southwark 12. Hammersmith and Fulham 28. Sutton 13. Haringey 29. Tower Hamlets 14. -

Review of Our Performance So Far

Draft: Final. APPENDIX 6: South Gloucestershire Council Climate Emergency Declaration Review of Year One of the Climate Emergency Action Plan South Gloucestershire Council Climate Emergency University Advisory Group UWE Bristol October 2020 1 Draft: Final. Index Section Page Executive Summary 3 Introduction and Context 8 South Gloucestershire’s Climate Emergency Process 10 South Gloucestershire’s Baseline 13 South Gloucestershire’s Climate Emergency Year 1 15 Action Plan Gaps in the Content of the Year 1 Plan 19 Year on Year Reduction in Emissions Required to 20 Meet the Target Areas of Focus for the Year 2 Plan 22 Recommendations for Improving Partnership Work 24 and Increasing Area Wide Engagement on the Climate Emergency Strategic Context (Political, Environmental, Social, 29 Technical, Legal, Economic) analysis Comparison of South Gloucestershire’s Climate Action 30 with that of North Somerset, Oxford, Plymouth and Wiltshire. Fit of South Gloucestershire’s Actions with the 42 National Policy Direction Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations 46 Appendix 1. 50 Setting Climate Commitments for South Gloucestershire. Quantifying the implications of the United Nations Paris Agreement for South Gloucestershire. Tyndall Centre Method Appendix 2. Oxford City Council Climate Emergency 52 Appendix 3. Wiltshire Climate Emergency 58 Appendix 4. North Somerset Climate Emergency 60 Appendix 5. Plymouth City Council Climate 62 Emergency Appendix 6. Global Warming of 1.5°C IPCC Special 64 Report. Summary Report for Policymakers Appendix 7 A Note on Terms 64 Note: All web sites accessed in September and October 2020 2 Draft: Final. Executive Summary South Gloucestershire Council asked UWE’ University Advisory Group to review Year One of the Climate Emergency Action Plan. -

Guide for Existing Businesses

OFFICIAL:SENSITIVE BUSINESS SUPPORT GUIDE FOR EXISTING BUSINESSES OFFICIAL:SENSITIVE FOREWORD Welcome to the Business Support Guide for businesses currently operating or looking to relocate to Britain’s Ocean City. There is a large and yet frequently changing amount of business support available making it a full time job for businesses to keep up. To make the process of finding appropriate support easier for businesses in the City, Plymouth City Council Economic Development Service produce and maintain two booklets focussed on helping start-ups and existing businesses to find support locally available: Click here to see Business Support Guide for Start Ups We aim to update this guide at six monthly intervals to ensure the contents stay relevant and up to date. The information in this guide is subject to change and was accurate when published in November 2019. If you notice any business support that has been left out, please contact us: E [email protected] www.investinplymouth.co.uk Plymouth City Council OFFICIAL:SENSITIVE SUPPORT SERVICE CONTACT COST PROVIDER Business Advice ACAS (Advisory, Provides free and impartial 0300 1231100 Free. Conciliation and information and advice to www.acas.org.uk Arbitration Service) employers and employees on all aspects of workplace relations and employment law. BEIS (Business, Brings together businesses and [email protected] There may be cost Energy and regulators to consider and www.gov.uk/government/org implications from the Industrial Strategy) change how local regulation is anisations/office-for-product- service provider. delivered and received, safety-and-standards promoting growth. Better Business for Up to date advice on business www.bbfa.biz There may be cost All regulation to help you achieve implications from the accepted standards at service provider. -

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB Members (July 2021)

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB members (July 2021) 1. Barnet (London Borough) 24. Durham County Council 50. E Northants Council 73. Sunderland City Council 2. Bath & NE Somerset Council 25. East Riding of Yorkshire 51. N. Northants Council 74. Surrey County Council 3. Bedford Borough Council Council 52. Northumberland County 75. Swindon Borough Council 4. Birmingham City Council 26. East Sussex County Council Council 76. Telford & Wrekin Council 5. Bolton Council 27. Essex County Council 53. Nottinghamshire County 77. Torbay Council 6. Bournemouth Christchurch & 28. Gloucestershire County Council 78. Wakefield Metropolitan Poole Council Council 54. Oxfordshire County Council District Council 7. Bracknell Forest Council 29. Hampshire County Council 55. Peterborough City Council 79. Walsall Council 8. Brighton & Hove City Council 30. Herefordshire Council 56. Plymouth City Council 80. Warrington Borough Council 9. Buckinghamshire Council 31. Hertfordshire County Council 57. Portsmouth City Council 81. Warwickshire County Council 10. Cambridgeshire County 32. Hull City Council 58. Reading Borough Council 82. West Berkshire Council Council 33. Isle of Man 59. Rochdale Borough Council 83. West Sussex County Council 11. Central Bedfordshire Council 34. Kent County Council 60. Rutland County Council 84. Wigan Council 12. Cheshire East Council 35. Kirklees Council 61. Salford City Council 85. Wiltshire Council 13. Cheshire West & Chester 36. Lancashire County Council 62. Sandwell Borough Council 86. Wokingham Borough Council Council 37. Leeds City Council 63. Sheffield City Council 14. City of Wolverhampton 38. Leicestershire County Council 64. Shropshire Council Combined Authorities Council 39. Lincolnshire County Council 65. Slough Borough Council • West of England Combined 15. City of York Council 40. -

M a Y O R ' S O F F I C E Bristol City Council Marvin Rees Website PO

Mayor Rees’ Diary June 2017 Thu 1st June Annual leave 17:00 Attend Executive Board Fri 2nd June 13:00 Officer meeting re review of the constitution 14:00 Officer meeting future of city leadership work 14:45 Telephone call with Metro Mayor candidate for Labour 15:15 Office time 17:30 Travel 18:00 Attend St Pauls Carnival Fact-Finding session Sat 3rd June 10:30 Attend Festival of Ideas talk by Bernie Sanders Sun 4th June 10:15 Attend Rush Sunday Civic Service Mon 5th June 08:00 Travel to Plymouth 11:00 Learning day with Chief Executive of Plymouth City Council and council officers 15:00 Travel to Bristol Tue 6th June 08:00 Weekly meeting with the Chief Executive 09:00 Attend City Office drop in session 09:45 Media: Record video for Fairfield High school assembly 10:00 Officer briefing on transport 11:00 Attend City Office drop in session 11:30 Meeting with Chief Executive and Deputy Chief Executive of Arts Council England 12:30 Meeting Managing Director of Generator 13:00 Attending bi monthly Political Cabinet meeting 14:30 Meeting Cabinet Member for Children and Young People 15:00 Media: Filming for consultation launch 16:00 Meeting Yale Programme intern 16:30 Telephone call with Chief Executive of Creative England M a y or’s Office Bristol City Council Marvin Rees Website PO Box 3176 Mayor of Bristol www.bristol.gov.uk Bristol BS3 9FS Wed 7th June 08:00 Attend Staff Engagement event ‘Hot Coffee, Hot Topic’ on fostering 09:15 Officer meeting re review of the constitution 10:00 Travel 10:30 Visit Bristol Gateway School 11:30 Travel to office -

Q2 1617 LA Referrals

Referrals to Local Authority Adoption Agencies from First4Adoption by region Q2 July-September 2016 Yorkshire & The Humber LA Adoption Agencies North East LA Adoption Agencies Durham County Council 13 North Yorkshire County Council* 30 1 Northumberland County Council 8 Barnsley Adoption Fostering Unit 11 South Tyneside Council 8 Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council 11 2 North Tyneside Council 5 Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council 10 Redcar Cleveland Borough Council 5 Hull City Council 10 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Middlesbrough Council 3 East Riding Of Yorkshire Council 9 City Of Sunderland 2 Cumbria County Council 7 Gateshead Council 2 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council 6 1 Newcastle Upon Tyne City Council 2 0 3.5 7 10.5 14 Leeds City Council 6 1 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Doncaster Metropolitan Borough Council 5 Hartlepool Borough Council 4 North Lincolnshire Adoption Service 4 1 City Of York Council 3 North East Lincolnshire Adoption Service 3 1 Darlington Borough Council 2 Kirklees Metropolitan Council 2 1 Sheffield Metropolitan City Council 2 Wakefield Metropolitan District Council 2 * Denotes agencies with more than one office entry on the agency finder 0 10 20 30 40 North West LA Adoption Agencies Liverpool City Council 30 Cheshire West And Chester County Council 16 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council 11 1 Manchester City Council 9 WWISH 9 Lancashire County Council 8 Oldham Council 8 1 Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council 8 2 Web Referrals Phone Referrals Wirral Adoption Team 8 Salford City Council 7 3 Bury Metropolitan -

Update on Further Tender Opportunities for 2018 Contract Work on 28

28 March 2018 – Update on further tender opportunities for 2018 contract work On 28 February 2018 we published an update on the procurement process for 2018 civil legal aid contracts. This document provides further information about the tender opportunities that will open shortly to award additional: Face to face advice contracts; Housing Possession Court Duty Scheme (“HPCDS”) contracts; and Civil Legal Advice (“CLA”) specialist telephone advice contracts. Face to face services On 28 February we confirmed that as a result of the procurement process, there had been a good level of demand for face to face advice contracts. We also confirmed there were a small number of areas where the LAA wished to secure greater provision. We expect these tenders for additional face to face contract work to begin in late April 2018. We will be seeking additional services in the following areas only: a) 7 family procurement areas where fewer than five compliant bids were received; b) 39 housing and debt procurement areas where one or fewer compliant bids were received; and c) 6 immigration and asylum access points where one or fewer compliant bids were received. Annex A lists the procurement areas / access points in which we will be advertising additional face to face advice services. Any organisation who can meet the minimum contract requirements will be able to tender to deliver the advertised contract work under a 2018 Standard Civil Contract. This includes organisations that have already tendered for a 2018 Standard Civil Contract who wish to open additional offices in the advertised procurement areas /access points and organisations who have not previously tendered. -

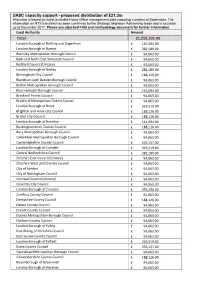

UASC Capacity Support - Proposed Distribution of £21.3M Allocation Is Based on Latest Available Home Office Management Data Capturing Numbers at September

UASC capacity support - proposed distribution of £21.3m Allocation is based on latest available Home Office management data capturing numbers at September. The information on NTS transfers has been confirmed by the Strategic Migration Partnership leads and is accurate up to December 2017. Please see attached FAQ and methodology document for further information. Local Authority Amount Total 21,258,203.00 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham £ 141,094.00 London Borough of Barnet £ 282,189.00 Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bath and North East Somerset Council £ 94,063.00 Bedford Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Bexley £ 282,189.00 Birmingham City Council £ 188,126.00 Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bournemouth Borough Council £ 141,094.00 Bracknell Forest Council £ 94,063.00 Bradford Metropolitan District Council £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Brent £ 329,219.00 Brighton and Hove City Council £ 188,126.00 Bristol City Council £ 188,126.00 London Borough of Bromley £ 141,094.00 Buckinghamshire County Council £ 188,126.00 Bury Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Cambridgeshire County Council £ 235,157.00 London Borough of Camden £ 329,219.00 Central Bedfordshire Council £ 282,189.00 Cheshire East Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Cheshire West and Chester Council £ 94,063.00 City of London £ 94,063.00 City of Nottingham Council £ 94,063.00 Cornwall Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Coventry City -

The Purpose of This Map Turning Plymouth

Opening Dec 2013 W City Centre Enlargement D R Key The Purpose of this Map E E E S E L R T V B R O A K E Y R T K M T R R C AS E A A E A K E D E P V A L O P R N R E A E R H L RT D T G V N D NO S R E U L T O E D N L ROA E I F C T S AR U T STU AS H D N E E E E E A D B A C E O H D SK I R A A T V D TH L RD R R O R O S P N D O A N P E R H L O P L H T P T T N FO G R J R A ST E I D A A PLYMOUTH CITYO COUNCILC E 0 S OAD E A PL L A D H N H R M L C A N RT P E RO NO Y S 25 E E E N R O B C A D 3 R E L K T E AC S R R O R 1 T R A S N B A TE KI N T L O A T S W DD E A A O S T H R P S S T Y D M O N A R A Y R L ST D O B E E PLYMOUTH A T R W AD D I T E O A E S E C R S M A TCH AS T G L ILL T A T E V R P OR D H E M N 3 LAN R E N RT A O L I L A P B T 8 E A Cycling Map N OR L O S W L A E 6 R OU A E T C ND R A T G R U E W H M R L ST E L E P A C S P R A R D WE M D D W S R O E Y OA O ' LANE A R ON JOHN E S A H N S A R T OE L D R RT E T B E H O L E N T U T R C Plymouth T S O L A S E Q L Marsh Mills Inset A D L Y T N T A I S University T A R ON E LB P D O N O E T M A R E D S C N N T D I N A ER E V E E E N RE S E A N Y T E P E W L T T T D R T A DD R H O B L E S S S L M T This map is designed for regular cyclists or R A S A LEN A T E B H O T T Q EIM T R T S E T C D R P P U U R R ARE S LO R E R N T E N G E T O B those who are just thinking about using a C R H RID N E E O U GE S RO N R E T A E R T W D T P O C E E O S R bike, whether as a leisure activity or a means A GIBBON D I H M S S E L O E LO L E A NGB T C 3 N RID S M E CA N H 5 GE River Plym of getting around the city. -

Ref No. Consultee Name TPH0701 Ian Leamouth TPH0702

Ref No. Consultee Name TPH0701 Ian Leamouth TPH0702 Muhammed Ali TPH0703 R G Corbett TPH0704 J Duncan TPH0705 Matthew Georat TPH0706 M Arshad TPH0707 Huam Mikhaiel TPH0708 Hani Hakeem TPH0709 Ronia Kosta Shiwits TPH0710 Ataay Matay TPH0711 Hany Abadeer TPH0712 Ayman Francis TPH0713 Makram Assad TPH0714 Hani Wadi TPH0715 Mohammed Ashraf TPH0716 Sunderland Hackney Carriage Operators Association TPH0717 A J Simms TPH0718 Adrian Saunders MP - Torbay Taxi Licensed Association TPH0719 Andria Kundous TPH0720 B G Butrus TPH0721 Abdel-Nasser Zaki Sefain TPH0722 Victor Eliya Hanna TPH0723 Mohammad Yaqoob TPH0724 Samer Botrous TPH0725 Godet Fikrry TPH0726 Basharat Naveed Maliq TPH0727 Robert J Lee TPH0728 Tom Terrett - Trading Standard and Licensing, Sunderland City Council TPH0729 Khalid Khokhar TPH0730 B Coomhar TPH0731 Emil R Sadig TPH0732 Shafig Bahir Shakir TPH0733 Nabil Eshag TPH0734 Meina Boshara TPH0735 Eilia Bashir TPH0736 Magi Gilada TPH0737 Mohammed Sajjad TPH0738 Said Mustafa TPH0739 Samih Butrous TPH0740 A Mahmood TPH0741 M Sawarb TPH0742 Khalid Mahmood Butt TPH0743 Farooq Ahmed TPH0744 Basilious Sidhom Basilious TPH0745 Mena Dawod TPH0746 George Gerjis TPH0747 Franso Awadalla TPH0748 Girgis Hismat Fawzi TPH0749 Mohib Shokri Murlous TPH0750 Nagy M Shakir TPH0751 Gigi Corboveanu TPH0752 Hani Ibrahim TPH0753 P C Arnold TPH0754 George Sidarous TPH0755 Nihad Fawiz TPH0756 D Metcalfe TPH0757 Terry Back TPH0758 George Hakim TPH0759 Nasr Mansie Moharib TPH0760 Margaret Loeke TPH0761 M Shaib TPH0762 Ramj Abdel Malik TPH0763 Abdul Wadud Choudhury -

Plymouth Plan Part One 2011 to 2031 (Consultation Draft)

Transport connectivity University Transport capacity Improving health inequalities TransportTransport capacity model shift Primary school Sports hub a c b Hospital Transport quality Long term gateway conditions Higher & secondary Knowledge education industries Healthy choices Marine industries OBJECTIVE £ Dockyard £ OBJECTIVE Longer lives Business/ £ energy park MoD OBJECTIVE £ Offices THEME THEME Distribution £ THEME VALUE OBJECTIVE £ Ocean city Sporting excellence Strengthening communities Key views 1 THEME Joint working Local identity Visitor economy Building design Waterfront ROOTS OBJECTIVE x THEME x THE PEOPLES TIMELINE 2015 2020 2025 2031 PLAN VALUE Four greens Integrated New Derriford community health and primary district Electrification trust social care schools centre of train line systems Mayflower Greenscape History 2020 trust centre North New prospect parks regeneration THEME Forder complete valley Marine OPPORTUNITY Play space link road industries VALUE production OBJECTIVE campus THEME Local employment Millbay Boulevard JOBS Community THEME safety AREA OBJECTIVEGrow food Local food Climate Equal change chances OBJECTIVE N Museum North S = Water quality South Heritage assets E Carbon emissions East 2 THE W CO Local green space Cultural hub West PLYMOUTH CC City centre Strategic parks Creative PLAN industries WF Waterfront 2011-2031 D Derriford Jan 2015 Part One Consultation Draft The cover used for the Plymouth Plan shows a range of issues and opportunities the plan addresses. It is also a key for all the symbols which are used in the plan: 5 principles: the basic values and beliefs that create the conditions to drive the city forward; 9 themes: the breadth of what the Plymouth Plan covers; 100 objectives: the goals and topics that the Plymouth Plan strategic objectives will deliver; 5 actions: an indication of the way the objectives can be achieved; areas: to help identify which parts of the plan are relevant to you; 7 WF Included is a timeline to help identify when we expect key strategic objectives of the Plymouth Plan to be realised.