No More Excuses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Issue

Scottish Left Review Issue 79 November/December 2013 £2.00 Comment Scottish Left Review Issue 79 November/December 2013 t is difficult to maintain constitutional Ineutrality at this tail-end of 2013. Of course we will continue to do our best to keep the SLR open as a space for Contents anyone on the Scottish left, a place where they can feel at home and contribute Comment .......................................................2 to a debate that stretches beyond the boundaries of party or constitutional Democracy in writing ....................................4 position. That is our duty as a magazine Jean Urquhart created expressly for that purpose. Solid foundations for change .........................6 But the duty lies not only on us to Michael Keating keep that space open but on all sides to fill that space. Because it can surely not Our share of the future ..................................8 be possible for us to face the desolation Robin McAlpine which lies across Scottish society in the dog-days of this unlucky year without Graveyard or get-together ..........................10 some sort of answer to what lies all Isobel Lindsay around us. Welfare Nation State ...................................12 What answer to Grangemouth? John McInally Facile talk of ‘the need to work together’ is an insult to the collective intelligence. Labour and the trade unions .......................14 All it states is that if we keep the fork Gregor Gall, Richard Leonard, Bob Crow and let others keep the knife, it will be impossible for us to eat on our own. That Real energy answers ...................................18 may not be a bad thing, but someone Andy Cumbers needs to explain why. -

Apprentice Strikes in Twentieth Century UK Engineering and Shipbuilding*

Apprentice strikes in twentieth century UK engineering and shipbuilding* Paul Ryan Management Centre King’s College London November 2004 * Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the International Conference on the European History of Vocational Education and Training, University of Florence, the ESRC Seminar on Historical Developments, Aims and Values of VET, University of Westminster, and the annual conference of the British Universities Industrial Relations Association. I would like to thank Alan McKinlay and David Lyddon for their generous assistance, and Lucy Delap, Alan MacFarlane, Brian Peat, David Raffe, Alistair Reid and Keith Snell for comments and suggestions; the Engineering Employers’ Federation and the Department of Education and Skills for access to unpublished information; the staff of the Modern Records Centre, Warwick, the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, the Caird Library, Greenwich, and the Public Record Office, Kew, for assistance with archive materials; and the Nuffield Foundation and King’s College, Cambridge for financial support. 2 Abstract Between 1910 and 1970, apprentices in the engineering and shipbuilding industries launched nine strike movements, concentrated in Scotland and Lancashire. On average, the disputes lasted for more than five weeks, drawing in more than 15,000 young people for nearly two weeks apiece. Although the disputes were in essence unofficial, they complemented sector-wide negotiations by union officials. Two interpretations are considered: a political-social-cultural one, emphasising political motivation and youth socialisation, and an economics-industrial relations one, emphasising collective action and conflicting economic interests. Both interpretations prove relevant, with qualified priority to the economics-IR one. The apprentices’ actions influenced economic outcomes, including pay structures and training incentives, and thereby contributed to the decline of apprenticeship. -

Heroes of Peace Profiles of the Scottish Peace Campaigners Who Opposed the First World War

Heroes of Peace Profiles of the Scottish peace campaigners who opposed the First World War a paper from the Introduction The coming year will see many attempts to interpret the First World War as a ‘just’ war with the emphasis on the heroic sacrifice of troops in the face of an evil enemy. No-one is questioning the bravery or the sacrifice although the introduction of conscription sixteen months after the start of the war meant that many of the men who fought did not do so from choice and once in the armed forces they had to obey orders or be shot. Even many of the volunteers in the early stages of the war signed up on the assumption that it would all be over in a few months with few casualties. We want to ensure that there is an alternative – and we believe more valid – interpretation of the events of a century ago made available to the public. This was a war in which around ten million young men were killed on the battlefield in four years, about 120,000 of them were Scottish. Proportionately Scotland suffered the highest number of war dead apart from Serbia and Turkey. It was described as the ‘war to end wars’ but instead it created the conditions for the rise of Hitler and the Second World War just twenty years later as a result of the very harsh terms imposed on Germany and the determination to humiliate the losing states. It also contributed to some of the current problems in the Middle East since, as part of the war settlement, Britain and France took ownership of large parts of the Ottoman Empire and divided up the territory with no reference to the identities and interests of the people. -

We Can Be Heroes Just for One Day

ASLEFJOURNAL SEPTEMBER 2019 The magazine of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers & Firemen We can be heroes just for one day Standing by the wall I will be king & you, you will be queen And the guns shot above our heads For ever and ever And the shame was on the other side. We can beat them... The train drivers ’ Inside: Palestine; Pride; Michael Green; and Tolpuddle 2019 union since 1880 GS Mick Whelan ASLEFJOURNAL SEPTEMBER 2019 Chaos and confusion The magazine of the Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers & Firemen E HAVE never been in the W game of having preferences in contractual negotiations for franchises, even having different standards of Mick: ‘It’s the old cap industrial relations and collar process’ within certain groups. Our issue is, and always has been, with the model. Never has this been clearer than now, when we might have expected 10 a period of calm after Mr Grayling going and Mr 12 Shapps taking over. Alas, that is not the case. Confusion reigns. News The number of questions we have had over what has been announced continues to grow. l Rail fares rise again; and steam train blues 4 Apparently, Southeastern is to be run again as l Railway Workers’ Centenary Service; and 5 the conditions aren’t right; Stagecoach and Arriva Off the Rails: Patrick Flanery; Bev Quist; can take legal action over being excluded. Then Kim Darroch; and Christopher Meyer First Trenitalia wins the former Virgin bid because it meets Williams – a report we have not yet had – Cyril Power’s Tube train pictures on show 6 l and contains element of the old cap and collar l Kevin Lindsay hails a victory in Scotland 7 process that means the franchisee cannot lose. -

SLR I15 March April 03.Indd

scottishleftreview comment Issue 15 March/April 2003 A journal of the left in Scotland brought about since the formation of the t is one of those questions that the partial-democrats Scottish Parliament in July 1999 Imock, but it has never been more crucial; what is your vote for? Too much of our political culture in Britain Contents (although this is changing in Scotland) still sees a vote Comment ...............................................................2 as a weapon of last resort. Democracy, for the partial- democrat, is about giving legitimacy to what was going Vote for us ..............................................................4 to happen anyway. If what was going to happen anyway becomes just too much for the public to stomach (or if Bill Butler, Linda Fabiani, Donald Gorrie, Tommy Sheridan, they just tire of the incumbents or, on a rare occasion, Robin Harper are actually enthusiastic about an alternative choice) then End of the affair .....................................................8 they can invoke their right of veto and bring in the next lot. Tommy Sheppard, Dorothy Grace Elder And then it is back to business as before. Three million uses for a second vote ..................11 Blair is the partial-democrat par excellence. There are David Miller two ways in which this is easily recognisable. The first, More parties, more choice?.................................14 and by far the most obvious, is the manner in which he Isobel Lindsay views international democracy. In Blair’s world view, the If voting changed anything...................................16 purpose of the United Nations is not to make a reasoned, debated, democratic decision but to give legitimacy to the Robin McAlpine actions of the powerful. -

Eet/S4/14/10/A Economy, Energy And

EET/S4/14/10/A ECONOMY, ENERGY AND TOURISM COMMITTEE AGENDA 10th Meeting, 2014 (Session 4) Wednesday 2 April 2014 The Committee will meet at 9.30 am in Committee Room 4. 1. Scotland's Economic Future Post-2014: The Committee will take evidence from— Iain McMillan, CBE, Director, CBI Scotland; Owen Kelly, OBE, Chief Executive, Scottish Financial Enterprise; David Watt, Regional Director, Institute of Directors Scotland; Colin Borland, Head of External Affairs, Scotland, Federation of Small Businesses; Garry Clarke, Head of Policy and Public Affairs, Scottish Chambers of Commerce; and then from— Stephen Boyd, Assistant Secretary, Scottish Trades Union Congress; Professor Mike Danson, Professor of Enterprise Policy, Heriot-Watt University; Robin McAlpine, Director, Jimmy Reid Foundation. 2. Scotland's Economic Future Post-2014- Review of evidence heard (in private): The Committee will review the evidence heard at today's meeting. EET/S4/14/10/A Fergus Cochrane Clerk to the Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee Room T2.60 The Scottish Parliament Edinburgh Tel: 0131 348 5230 Email: [email protected] EET/S4/14/10/A The papers for this meeting are as follows— Agenda item 1 Note from the clerk EET/S4/14/10/1 PRIVATE PAPER EET/S4/14/10/2 (P) EET/S4/14/10/1 Economy, Energy and Tourism Committee 10th Meeting, 2014 (Session 4), Wednesday, 2 April 2014 Scotland’s Economic Future Post-2014 Introduction 1. This paper provides background information for the Committee’s sixth evidence session of its inquiry into Scotland’s economic future post 2014. The theme for this session is ‘economic sectors, regulation, trade, labour markets’. -

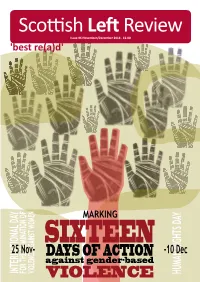

Scottish Leftreview

ScottishLeft Review Issue 96 November/December 2016 - £2.00 'best re(a)d' 1 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 96 November/December 2016 LRD TUC Sept15_Layout 1 10/07/2015 14:09 Page 1 FIGHT ANTI-UNION LAWS www.rmt.org.uk General Secretary: Mick Cash President President: PSeaneter P iHoylenkney ASLEF CALLS FOR AN INTEGRATED, PUBLICLY OWNED, ACCOUNTABLE RAILWAY FOR SCOTLAND (which used to be the SNP’s position – before they became the government!) Mick Whelan Tosh McDonald Kevin Lindsay General Secretary President Scottish Ocer ASLEF the train drivers union- www.aslef.org.uk 2 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 96 November/December 2016 feedback comment Back to the future and forward to the past he Jimmy Reid Foundation, the Foundation, it was my duty and Labour (instead of Blair, Brown and sister organisation of Scottish honour to give the vote of thanks Miliband, and the array of Scottish TLeft Review, held its annual at the end of the lecture. I took the Labour leaders – Dewar, McLeish, lecture on Thursday 6 October. This opportunity to say that I was sure that McConnell, Gray, Alexander, Lamont, year, the fourth annual lecture, was Jimmy Reid would have welcomed reviews Murphy and now Dugdale). Corbyn’s given by Jeremy Corbyn. He received Jeremy’s election and re-election to refusal to support independence a rapturous reception before he had the leadership of the Labour party. would not have been such an issue in uttered a word and then afterwards a This was for various reasons, all these circumstances as it would have standing ovation from the majority of centred around the point that Corbyn been counter-balanced by his more the 600-odd people gathered in the is the Labour leader that many on the left-wing policies so that far fewer Govan Old Parish Church that night. -

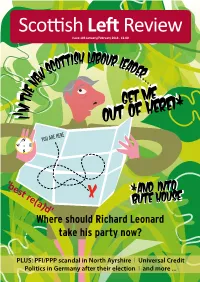

Scottish Leftreview

ScottishLeft Review Issue 103 January/February 2018 - £2.00 'best re(a)d' PLUS: PFI/PPP scandal in North Ayrshire I Universal Credit Politics in Germany after their election I and more ... 1 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 103 January/February 2018 ASLEF CALLS FOR AN INTEGRATED, PUBLICLY OWNED, ACCOUNTABLE RAILWAY FOR SCOTLAND (which used to be the SNP’s position – before they became the government!) Mick Whelan Tosh McDonald Kevin Lindsay General Secretary President Scottish Ocer ASLEF the train drivers union- www.aslef.org.uk 2 - ScottishLeftReview Issue 103 January/February 2018 feedback comment 2018: here we go cottish Left Review wholeheartedly interview with Richard, we have asked campaign, it became clear that Leonard welcomes the election of Richard others to lay out their perspectives on did not command a majority of support SLeonard to the leadership of what difference his election makes and from his parliamentary colleagues in Scottish Labour. As outlined in the last what difference he may make in future. the 24 strong Labour group at Holyrood. editorial, his election was we argued to Indeed, the composition of his front He won by a sizable margin (57% to 43%) be a benefit to all of the left in the age bench team reflects this, with the likes of overall but not amongst individual party of the hegemony of austerity and neo- Jackie Ballie, Sarwar and Iain Gray in its members (52% to 48%) or registered liberalism. How much worse off the left ranks. supporters (48% to 52%), indicating that reviews would have been without his election despite progress being made the right is What this all means is that the task can be gleaned when one considers not still a considerable force within Scottish of Scottish Labour under Leonard’s just his competitor’s personal behaviour Labour. -

The Scottish Independence Referendum and After

THE SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE REFERENDUM AND AFTER Michael Keating Professor of Politics at the University of Aberdeen, and director of the Centre on Constitutional Change SUMMARY: The Scottish Dilemma. – Constitutional Traditions in Scotland. – The Na- tionalists in Government. – The Battle Ground. – Economy and Finance. – Welfare. – Defence and Security. – Europe. – The Campaign. – The Outcome. – The Aftermath. – The Smith Report. – EVEL and Barnett. – The European Context. – The Future of the State. – Abstract – Resum – Resumen. The Scottish Dilemma The Scottish independence referendum on 18 September 2014 was a highly unusual event, an agreed popular vote on secession in an advanced industrial democracy. The result, with 45 per cent for in- dependence and 55 per cent against, might seem to have settled the question decisively. Yet, paradoxically, it is the losing side that has emerged in better shape and more optimistic, while the winners have been plunged into difficulties. In order to understand what has hap- pened, we need to examine the referendum in light of the evolution of the United Kingdom and the changing place of Scotland within it. Scotland should be seen as a case of the kind of spatial rescaling that is taking place more generally across Europe, as new forms of state- hood and of sovereignty evolve. Scottish public opinion favours more self-government but no longer recognizes the traditional nation-state model presented in the referendum question. Article received 12/12/2014; approved 12/12/2014. 73 REAF núm. 21, abril 2015, p. 73-98 Michael Keating Constitutional Traditions in Scotland Since the late nineteenth century union, there have been three main constitutional traditions in Scotland. -

D21 Programme5.Indd

DEMOCRACY 21: Let’s Build a Democracy Fit for the 21st Century DEM Welcome Thank you for attending Democracy 21 and taking an active interest in the future of Scottish democracy. This conference starts with the premise that people should have collective OCR power to make good things happen for themselves and their communities and to stop bad things happening. This is a simple definition of power. Democracy is the most equal distribution of that power possible. By bringing together community groups, democratic innovators, academics, legislators, local and national politicians, civil servants, civil society activists, community organisers, political activists, futurists, artists and creators we can collectively discuss the challenges for democracy today. We hope this will be a space for generating innovative ideas ACY about how we can make a better democracy. Today is also the launch of a declaration, developed by and for community activists, that will shape the Local Democracy Bill to advance an ambitious plan for local government reform. 21 Let’s build a democracy fit for the 21st Century. How did we get here? Scotland is a great teacher about modern politics. The politics here is more open and inclusive than it is in Westminster and we think that is partly to do with better electoral systems. We also know that being better at democracy than Westminster is not getting over a particularly high bar. Scotland does not escape the inequality, confusion and precariousness that is fuelling volatility across the globe, which forms the backdrop to the discussions that we will have today. This makes it clear to us that democracy is not only about elections. -

A Brief History of Govan

A Brief History of Govan..... 500 Around 500 AD, according to tradition, the Christian missionary St Constantine arrives in Govan and builds a small wooden church next to a sacred well and in the shadow of the ceremonial hill. The first Christian Govanites are buried in the heart-shaped burial ground which now surrounds Govan Old Church. The people of Govan and the Clyde Valley in these early times are called 'Britons'. They're different from their neighbours, the Scots and Picts, and speak their own language. In this language the name Govan means 'little hill'. 650 The church and the ceremonial hill at Govan are part of the kingdom of the Clyde Britons which is ruled from Dumbarton Rock. The king of Dumbarton has just won a great victory over the Scots of Dalriada (now Argyll) and has become one of the most powerful kings in the British Isles. 756 A combined army of Picts and Northumbrians attacks Dumbarton and forces the Clyde Britons to surrender. The invaders are recorded as having forded the River Clyde at Govan, and the actual surrender may have taken place in a ceremony on the ancient hill of Govan. 850 Around the mid to late 800s the richly decorated Govan Sarcophagus is carved from a single block of stone. It is a high status burial monument, replete with interlace designs and figurative panels, including a scene portraying a mounted warrior hunting, a symbolic motif which combines ideas of military prowess with the Christian quest for salvation. Whether it was intended to hold the relics of a saint or the bones of a king is impossible to tell, but it is undoubtedly one of the most outstanding pieces of sculpture of its age. -

Nazioni E Regioni 4/2014

ISSN: 2282-5681 Nazioni Regionie Studi e ricerche sulla comunità immaginata (4)2014 CARATTERI ( )e MOBILI Direzione Dario Ansel, Fabio De Leonardis, Andrea Geniola Caporedattrice Francesca Zantedeschi Redazione Adriano Cirulli, Arcangelo Licinio, Marco Pérez, Paolo Perri, Gianluca Scroccu, Marco Stolfo Contatti [email protected] / www.nazionieregioni.it Comitato scientifico Joseba Agirreazkuenaga (Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea), Ferran Archilés (Universitat de València), Alfonso Botti (Università degli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia), Jordi Canal (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales - Paris), Guido Franzinetti (Università del Piemonte Orientale), Maarten Van Ginderachter (Universiteit Antwerpen), José Luis de la Granja Sainz (Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea), Miroslav Hroch (Univerzita Karlova v Praze), Michel Huysseune (Vesalius College - Vrije Universiteit Brussel), James Kennedy (University of Edinburgh), Juan Carlos Moreno Cabrera (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid), Xosé Manoel Núñez Seixas (Universidade de Santiago de Compostela/Ludwig- Maximilians-Universität München), Rolf Petri (Università “Ca’ Foscari” Venezia), Daniele Petrosino (Università degli Studi di Bari “Aldo Moro”), Ilaria Porciani (Alma Mater Studiorum - Università di Bologna), Anne-Marie Thiesse (École Normale Supérieure - Paris), Stuart Woolf (Università “Ca’ Foscari” Venezia), Pere Ysàs (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) Comitato editoriale Alex Amaya Quer (CEFID - Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona), Leyre Arrieta (Deustuko Unibertsitatea), Gevorg