Casacuba Cultural Resources Assessment Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

Some Pre-Boom Developers of Dade County : Tequesta

Some Pre-Boom Developers of Dade County By ADAM G. ADAMS The great land boom in Florida was centered in 1925. Since that time much has been written about the more colorful participants in developments leading to the climax. John S. Collins, the Lummus brothers and Carl Fisher at Miami Beach and George E. Merrick at Coral Gables, have had much well deserved attention. Many others whose names were household words before and during the boom are now all but forgotten. This is an effort, necessarily limited, to give a brief description of the times and to recall the names of a few of those less prominent, withal important develop- ers of Dade County. It seems strange now that South Florida was so long in being discovered. The great migration westward which went on for most of the 19th Century in the United States had done little to change the Southeast. The cities along the coast, Charleston, Savannah, Jacksonville, Pensacola, Mobile and New Orleans were very old communities. They had been settled for a hundred years or more. These old communities were still struggling to overcome the domination of an economy controlled by the North. By the turn of the century Progressives were beginning to be heard, those who were rebelling against the alleged strangle hold the Corporations had on the People. This struggle was vehement in Florida, including Dade County. Florida had almost been forgotten since the Seminole Wars. There were no roads penetrating the 350 miles to Miami. All traffic was through Jacksonville, by rail or water. There resided the big merchants, the promi- nent lawyers and the ruling politicians. -

Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources

Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources Everglades National Park was created primarily because of its unique flora and fauna. In the 1920s and 1930s there was some limited understanding that the park might contain significant prehistoric archeological resources, but the area had not been comprehensively surveyed. After establishment, the park’s first superintendent and the NPS regional archeologist were surprised at the number and potential importance of archeological sites. NPS investigations of the park’s archeological resources began in 1949. They continued off and on until a more comprehensive three-year survey was conducted by the NPS Southeast Archeological Center (SEAC) in the early 1980s. The park had few structures from the historic period in 1947, and none was considered of any historical significance. Although the NPS recognized the importance of the work of the Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs in establishing and maintaining Royal Palm State Park, it saw no reason to preserve any physical reminders of that work. Archeological Investigations in Everglades National Park The archeological riches of the Ten Thousand Islands area were hinted at by Ber- nard Romans, a British engineer who surveyed the Florida coast in the 1770s. Romans noted: [W]e meet with innumerable small islands and several fresh streams: the land in general is drowned mangrove swamp. On the banks of these streams we meet with some hills of rich soil, and on every one of those the evident marks of their having formerly been cultivated by the savages.812 Little additional information on sites of aboriginal occupation was available until the late nineteenth century when South Florida became more accessible and better known to outsiders. -

Download the Press Release

Florida Department of Transportation RON DESANTIS 1000 N.W. 111 Avenue KEVIN J. THIBAULT, P.E. GOVERNOR Miami, Florida 33172 SECRETARY For Immediate Release Contact: Tish Burgher April 22, 2020 (305) 470-5277 [email protected] Governor DeSantis Announces Upcoming Contract for Tamiami Trail Next Steps Phase 2 MIAMI, Fla. – Today, Governor Ron DeSantis announced the upcoming contract advertisement for the State Road (SR) 90/Tamiami Trail Next Steps Phase 2 Project. “I have worked diligently with the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) and the National Park Service (NPS) to accelerate this critical infrastructure project,” said Governor Ron DeSantis. “The Tamiami Trail project is a key component of the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan. Elevating the trail will allow for an additional 75 to 80 billion gallons of water a year to flow south into the Everglades and Florida Bay.” In June 2019, Governor DeSantis announced that full funding had been secured to complete the project to elevate the Tamiami Trail. The U.S. Department of Transportation awarded an additional $60 million to the state’s $40 million to fully fund the project, which is critical to the Governor’s plan to preserve the environment. “This is another example of how Governor DeSantis has made preserving our environment and improving Florida’s infrastructure among his top priorities,” said Florida Department of Transportation Secretary Kevin J. Thibault, P.E. “This important project advances both and will also provide much needed jobs.” “Expediting Everglades restoration has been one of the hallmarks of the Governor’s environmental agenda,” said Florida Department of Environmental Protection Secretary Noah Valenstein. -

Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs FY2019-20 Youth Arts Miami (YAM) Grant Award Recommendations

Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs FY2019-20 Youth Arts Miami (YAM) Grant Award Recommendations Grant #1 : - All Florida Youth Orchestra, Inc. dba Florida Youth Orchestra Award: Grant Amount 1708 N 40 AVE to be calculated based on Hollywood, Florida 33021 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support music education and outreach performances for 4,000 students, ages 5-18, at community sites and public venues in Miami-Dade County. Program activities will include orchestral training, violin/ percussion instruction for at-risk youth, family concerts for young children/seniors and outreach performances. Participants will engage in music education and benefit from improved musical skills and social/behavioral skills. Grant #2 : - Alliance for Musical Arts Productions, Inc. Award: Grant Amount 5020 NW 197 ST to be calculated based on Miami Gardens, Florida 33055 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support Alliance for Musical Arts' music programs for a total of 300 youth ages 7-18 and youth with disabilities up to age 22, at the Betty T. Ferguson Complex, in Miami Gardens. Youth Drum Line activities include classes in percussion and musical instrumentation. The “305” Community Band Camp, includes sight-reading, applied skill development, audition technique and rehearsals, two free performances open to the public, community performances, events, parades and demonstrations. Grant #3 : - American Children's Orchestras for Peace, Inc. Award: Grant Amount 2150 Coral Way #3-C to be calculated based on Miami, Florida 33145 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support American Children's Orchestras for Peace for 800 students ages 5-13, at Jose Marti Park, Shenandoah Park and Shenandoah Elementary, in the City of Miami. -

EL SISTEMA DE BIBLIOTECAS PÚBLICAS DE MIAMI-DADE Y Bibliotecas Municipales Asociadas Direcciones Y Horarios Correo Electrónico: [email protected]

EL SISTEMA DE BIBLIOTECAS PÚBLICAS DE MIAMI-DADE y Bibliotecas Municipales Asociadas www.mdpls.org Direcciones y Horarios Correo electrónico: [email protected] Horario de servicio (A menos que se indique lo contrario) Lunes a jueves 9:30 a.m. - 8:00 p.m. • Viernes y sábado 9:30 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. • Domingo - Cerrado 1 ALLAPATTAH 25 MAIN LIBRARY (DOWNTOWN) SERVICIOS ESPECIALES 1799 NW 35 St. · 305.638.6086 101 West Flagler St. · 305.375.2665 Lun. a Sab. 9:30 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. | Dom. Cerrado CONEXIONES 2 ARCOLA LAKES Servicio de Biblioteca en la Casa 8240 NW 7 Ave. · 305.694.2707 26 MIAMI BEACH REGIONAL 305.474.7251 227 22nd St. · 305.535.4219 3 BAY HARBOR ISLANDS STORYTIME EXPRESS 1175 95 St. · 786.646.9961 27 MIAMI LAKES Kits de alfabetización para los 6699 Windmill Gate Rd. · 305.822.6520 Centros de Educación Temprana 4 CALIFORNIA CLUB 305.375.4116 700 Ives Dairy Rd. · 305.770.3161 28 MIAMI SPRINGS 401 Westward Dr. · 305.805.3811 BIBLIOTECA AMBULANTE 5 CIVIC CENTER PORTA KIOSK 305.480.1729 Metrorail Civic Center Station · 29 MODEL CITY (CALEB CENTER) 305.324.0291 2211 NW 54 St. · 305.636.2233 BRAILLE Y LIBROS PARLANTES Lun. - Vie. 7:00 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. Lun. a Sab. 9:30 a.m. - 6:00 p.m. | Dom. Cerrado 305.751.8687 · 800.451.9544 Sab. y Dom. Cerrada 30 NARANJA 6 COCONUT GROVE 14850 SW 280 St. · 305.242.2290 TDD DEL SISTEMA 2875 McFarlane Rd. · 305.442.8695 31 NORTH CENTRAL (DISPOSITIVO DE TELECOMUNICA- CIONES PARA SORDOS) 7 CONCORD 9590 NW 27 Ave. -

City of Miami Beach Zoning

87TH TER GU RM-2 N 87TH ST 86TH ST 86TH ST 85TH ST TH ST TH 85 E BISCAYNE BEACH E V V E A A V GU S G A DR STILLWATER N N I N T I 4TH ST 84TH S L RS-4 8 D O L R R O Y A C B H 83RD ST GU 83RD ST GU RM-1 82ND TER 82ND ST 82ND ST 82ND ST GU 81ST ST y a ST ST D 81 80TH ST V D L w R T B N I r OI P P S e E E BISCAYNE POINT YN 79TH TER R t GU 80TH ST CA C BIS N E a N E V L V A AND RD W R CLEVEL A E C D N D A Y I A ZON O T S S IN M 79TH L W D Y E m G R RS-4 GU E A A R I E N B u T O A E S RM-1 C B N RS-4 M t IA RD IS W I DAYTON H C AYN E a M 78TH ST F PO U E A E RS-3 IN T RS-3 E T T A E V V E R E T V D V A F A V V A A P A A S G T E N S N N T I I OF THE L T N L S H O O T O 77 Y D L E L R B R K O Y R B A C C B A A I H C D V M RS-4 A H ST I 76T T R DR C SHORE D N H R RS-3 O E E N 75TH ST L T S L N T S AY DR CITY OF IRW A FA E T E V C RS-4 A O NORMANDY SHORES S N A H ST 74T O R GU CD-2 A W R Z A E Y Y N N B S E MXE T RM-1 A G V A E 73RD ST R Y RM-1 A B V E R A GU Y TH GU A Y D R S 72ND ST MIAMI BEACH A T B R B D TC-3(c) O E TC-2 R RM-1 RO TC-3 T HO T H S A T ST S GU TC-1 71S A 71ST ST V G E E GU N GU GU • FLORIDA • J S R TC-3(C) D O RO T LE R TC-3 GU N IL U S STCD-2 GU E E E GU GU S E NID S O RS-3 R N IM RS-4 A R A TC-3 TC-3(c) S D M Y O M RM-2 T D T BR N R R A ES TC-2 69TH ST M E RO U T E R E S INCORPORATED 1915 O D P L N A V AN M A R ST E D U E R E R GU RM-3 E ST R U AIS D S CAL T B 1 E 7 E E R O A I N V V V O R R I G RM-1 L D A E D RM-2 A D ADOPTED 21ST DAY OF SEPTEMBER, 1989 U B R L I R E Z A T S V G I D A I E A RM-1 A R N U I N U N R S RM-1 L -

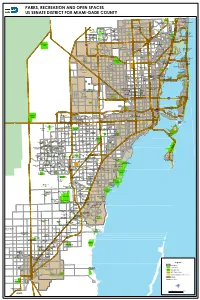

Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces Us Senate District for Miami-Dade County

PARKS, RECREATION AND OPEN SPACES US SENATE DISTRICT FOR MIAMI-DADE COUNTY S A N NE 215TH ST NE 213TH ST S I Ives Estates NW 215TH ST M E ST NW 215TH E V O N A N E Y H Park P T 2 W 441 N 9 X ST A NE 207TH 3 E D Y ¤£ W E A V N K N Highland Oaks E P W NW 207TH ST Ives Estates NE 2 T 05T H H ST ST GOLDEN BEACH NW 207T 1 NW 207TH ST A 5 D D T I V Park H L R Tennis CenterN N N B A O E E 27 NW E L 2 V 03RD ST N £ 1 ¤ 1 F E N NW T N 2 20 A 3RD ST T 4 S 2 6 E W E T T E H T NE 199TH S T V T H H 9 1 C H 3 A 9 AVENTURA R 1 0 TE D O 3R Ï A 0 9 2 NW E A A T D V T N V V H H N E H ST E 199T E ND ST NW 2 W 202 N A Sierra C Y V CSW T W N N E HMA N LE Chittohatchee Park E ILLIAM W Park NE 193RD ST 2 Country Club 2 N N T W S D 856 H 96TH ST Ojus T NW 1 at Honey Hill 9 7 A UV Country Lake 19 T Snake Creek W V of Miami H T N T S E N NW 191S W Acadia ST ST A NW 191 V Park N Park 1 E Trail NE 186TH ST ST 2 Area 262 W NW 191ST T T H 5TH S 4 NE 18 Park 7 A Spanish Lake T V H E A V NE 183RD ST Sunny Isles Country Village E NW 183RD ST DR NW 186TH ST NE MIAMI GARDENS I MIAMI GARDENS 179TH ST 7 North Pointe NE Beach 5 Greynolds N Park Lake Stevens E N W R X D E T H ST T E 177T 3 N S N Community Ctr. -

Florida's Paradox of Progress: an Examination of the Origins, Construction, and Impact of the Tamiami Trail

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Florida's Paradox Of Progress: An Examination Of The Origins, Construction, And Impact Of The Tamiami Trail Mark Schellhammer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Schellhammer, Mark, "Florida's Paradox Of Progress: An Examination Of The Origins, Construction, And Impact Of The Tamiami Trail" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2418. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2418 FLORIDA’S PARADOX OF PROGRESS: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ORIGINS, CONSTRUCTION, AND IMPACT OF THE TAMIAMI TRAIL by MARK DONALD SCHELLHAMMER II B.S. Florida State University, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 © 2012 by Mark Schellhammer II ii ABSTRACT This study illustrates the impact of the Tamiami Trail on the people and environment of South Florida through an examination of the road’s origins, construction and implementation. By exploring the motives behind building the highway, the subsequent assimilation of indigenous societies, the drastic population growth that occurred as a result of a propagated “Florida Dream”, and the environmental decline of the surrounding Everglades, this analysis reveals that the Tamiami Trail is viewed today through a much different context than that of the road’s builders and promoters in the early twentieth century. -

Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs FY2020-21 Youth Arts Miami (YAM) Grant Award Recommendations

Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs FY2020-21 Youth Arts Miami (YAM) Grant Award Recommendations Grant #1 : All Florida Youth Orchestra, Inc. dba Florida Youth Orchestra Award: Grant Amount 1708 N 40 AVE to be calculated based on Hollywood, Florida 33021 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support music education and outreach performances for 4,175 students, ages 5 - 18, at community sites and public venues in Miami-Dade County. Program activities will include orchestral training, violin / percussion instruction for at-risk youth, family concerts for young children / seniors and outreach performances. Participants will engage in music education and benefit from improved musical skills and social / behavioral skills. Grant #2 : Alliance for Musical Arts Productions, Inc. Award: Grant Amount 5020 NW 197 ST to be calculated based on Miami Gardens, Florida 33055 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support Alliance for Musical Arts’ Youth Drum Line program for 120 students ages 7 – 18, at the Betty T. Ferguson Complex and North Dade Regional Library in Miami Gardens. The FIND YOUR BEAT! outreach program will will engage 1,500 youth and families with free monthly performances and art exhibitions to improve the quality of life through the arts. Grant #3 : American Children's Orchestras for Peace, Inc. Award: Grant Amount 2150 Coral Way #3-C to be calculated based on Miami, Florida 33145 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support American Children's Orchestras for Peace programs for over 800 children plus numerous adults and audience members during this year-round curriculum held at Jose Marti Park and Shenandoah Park in the City of Miami. -

Transportation Element

TRANSPORTATION ELEMENT Introduction The purpose of the transportation element is to plan for an integrated multimodal transportation system providing for the circulation of motorized and non-motorized traffic in Miami-Dade County. The element provides a comprehensive approach to transportation system needs by addressing all modes of transportation—pedestrian and bicycle facilities, traffic circulation, mass transit, aviation and ports. The Transportation Element is divided into five subelements. The Traffic Circulation Subelement addresses the needs of automobile traffic, bicyclists and pedestrians. The Mass Transit Subelement addresses the need to continue to promote and expand the public transportation system to increase its role as a major component in the County's overall transportation system. The Aviation Subelement addresses the need for continued expansion, development and redevelopment of the County's aviation facilities; and the Port of Miami River and PortMiami Subelements continue to promote maritime business and traditional maritime related shoreline uses on the Miami River, and the expansion needs of PortMiami. The Adopted Components of the Transportation Element and each of the five subelements separately contain: 1) goals, objectives and policies; 2) monitoring measures; and 3) maps of existing and planned future facilities. These subelements are preceded by overarching goals, objectives and policies that express the County's intent to develop multi-modalism, reduce the County’s dependency on the personal automobile, enhance energy saving practices in all transportation sectors, and improve coordination between land use and transportation planning and policies. The Miami-Dade 2035 Long Range Transportation Plan (LRTP), is adopted to guide transportation investment in the County for the next 25 years. -

Project Descriptions

PROJECT DESCRIPTIONS Table of Contents Project Page PARKS, RECREATIONAL FACILITIES, & CULTURAL FACILITIES 72nd Street Park, Library, & Aquatic Center 1 Art Deco Museum Expansion 2 Baywalk 3 Collins Park 4 Crespi Park 5 Fairway Park 6 Fisher Park 7 Flamingo Park 8 La Gorce Park 11 Log Cabin Reconstruction 12 Lummus Park 13 Marjory Stoneman Douglas Park 14 Maurice Gibb Park 15 Middle Beach Beachwalk 16 Muss Park 17 North Beach Oceanside Park Beachwalk 18 North Shore Park & Youth Center 19 Palm Island Park 21 Par 3/Community Park 22 Pinetree Park 23 Polo Park 24 Roof Replacement for Cultural Facilities 25 Scott Rakow Youth Center 26 Skate Park 28 SoundScape Park 29 South Pointe Park 30 Stillwater Park 31 Tatum Park 32 Waterway Restoration 33 West Lots Redevelopment 34 NEIGHBORHOODS AND INFRASTRUCTURE 41st Street Corridor 35 Above Ground Improvements 36 Flamingo Park Neighborhood Improvements 37 La Gorce Neighborhood Improvements 38 Neighborhood Traffic Calming and Pedestrian-Friendly Streets 39 North Shore Neighborhood Improvements 40 Ocean Drive Improvement Project 41 Palm & Hibiscus Neighborhood Enhancements 42 Protected Bicycle Lanes and Shared Bike/Pedestrian Paths 43 Resilient Seawalls and Living Shorelines 44 Sidewalk Repair Program 45 Street Pavement Program 46 Street Tree Master Plan 47 Washington Ave Corridor 48 Table of Contents Project Page POLICE, FIRE, AND PUBLIC SAFETY Fire Station #1 49 Fire Station #3 50 LED Lighting in Parks 51 License Plate Readers 52 Marine Patrol Facility 53 Ocean Rescue North Beach Facility 54 Police