Cultural and Spatial Perceptions of Miami‟S Little Havana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida Baptist Heritage

Published by the FLORIDA BAPTIST HISTORICAL SOCIETY Dr. Mark A. Rathel Secretary-Treasurer 5400 College Drive Graceville, Florida 32440 (850) 263-3261 Fax: (850) 263-7506 E-mail: [email protected] Board of Directors The State Board of Missions of the Florida Baptist Convention elects the Board of Directors. Dr. John Sullivan Executive Director, Florida Baptist Convention Dr. Irvin Murrell Director of Library Services The Baptist College of Florida Curator, Florida Baptist Historical Collection Dr. R. C. Hammack, Chairman Administrative Vice-President The Baptist College of Florida Dr. Fred Donehoo, Vice-Chairman Christian School Consultant, Lake Placid Mrs. Toni Clevenger Pensacola Mrs. Patricia Parks School Superintendent, Hamilton County Journal of the Florida Baptist Historical Society Rev. John Hillhouse Florida Baptist Heritage Journalist, Lighthouse Point Mrs. Debbie Gillette Church Secretary, Indian Rocks, Largo Dr. David Gasperson Sherbrooke Baptist Church, Lake Worth Page 3 EDITORIAL Mark A. Rathel Page 5 A HISTORY OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FLORIDA BAPTISTS Sid Smith Page 29 A HISTORY OF NATIVE AMERICANS IN FLORIDA John C. Hillhouse, Jr. Page 42 FLORIDA BAPTIST Contents HISPANIC HERITAGE Milton S. Leach, Jr. Page 56 A HISTORY OF HAITIAN SOUTHERN BAPTIST CHURCHES IN FLORIDA Lulrick Balzora EDITORIAL PERSPECTIVE Mark Rathel Secretary Treasurer Florida Baptist Historical Society Welcome to the Second Issue of The Journal of Florida Baptist Heritage! Florida Baptists are a rich mosaic of cultures, traditions, and languages. Indeed, Florida Baptists minister in a context of international missions within the state boundaries. This second volume attempts to celebrate our diversity by reflecting on the history of selected ethnic groups in Florida Baptist life. -

Slum Clearance in Havana in an Age of Revolution, 1930-65

SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 by Jesse Lewis Horst Bachelor of Arts, St. Olaf College, 2006 Master of Arts, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jesse Horst It was defended on July 28, 2016 and approved by Scott Morgenstern, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science Edward Muller, Professor, Department of History Lara Putnam, Professor and Chair, Department of History Co-Chair: George Reid Andrews, Distinguished Professor, Department of History Co-Chair: Alejandro de la Fuente, Robert Woods Bliss Professor of Latin American History and Economics, Department of History, Harvard University ii Copyright © by Jesse Horst 2016 iii SLEEPING ON THE ASHES: SLUM CLEARANCE IN HAVANA IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION, 1930-65 Jesse Horst, M.A., PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 This dissertation examines the relationship between poor, informally housed communities and the state in Havana, Cuba, from 1930 to 1965, before and after the first socialist revolution in the Western Hemisphere. It challenges the notion of a “great divide” between Republic and Revolution by tracing contentious interactions between technocrats, politicians, and financial elites on one hand, and mobilized, mostly-Afro-descended tenants and shantytown residents on the other hand. The dynamics of housing inequality in Havana not only reflected existing socio- racial hierarchies but also produced and reconfigured them in ways that have not been systematically researched. -

Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961

Nikolaus Böttcher Trade, War and Empire: British Merchants in Cuba, 1762-17961 In the late afternoon of 4 March 1762 the British war fleet left the port of Spithead near Portsmouth with the order to attack and conquer “the Havanah”, Spain’s main port in the Caribbean. The decision for the conquest was taken after the new Spanish King, Charles III, had signed the Bourbon family pact with France in the summer of 1761. George III declared war on Spain on 2 January of the following year. The initiative for the campaign against Havana had been promoted by the British Prime Minister William Pitt, the idea, however, was not new. During the “long eighteenth century” from the Glorious Revolution to the end of the Napoleonic era Great Britain was in war during 87 out of 127 years. Europe’s history stood under the sign of Britain’s aggres sion and determined struggle for hegemony. The main enemy was France, but Spain became her major ally, after the Bourbons had obtained the Spanish Crown in the War of the Spanish Succession. It was in this period, that America became an arena for the conflict between Spain, France and England for the political leadership in Europe and economic predominance in the colonial markets. In this conflict, Cuba played a decisive role due to its geographic location and commercial significance. To the Spaniards, the island was the “key of the Indies”, which served as the entry to their mainland colonies with their rich resources of precious metals and as the meeting-point for the Spanish homeward-bound fleet. -

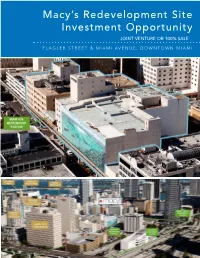

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

[email protected] 786-663-6511 November 23, 2020 City of Miami Office of Hearing Boards 444 SW

November 23, 2020 City of Miami Office of Hearing Boards 444 SW 2 Ave 3rd Floor Miami, FL 33130 RE: Appeal Tree Removal located at 2800 Shipping Avenue Process Number BD-20-006291-001 To whom it may concern: On behalf of the Coconut Grove Village Council and many residents of our village, we appeal the tree removal referenced above. Many neighborhoods in our village have undergone extensive development and been transformed over the years. Even though we all understand new development is inevitable, new construction can be achieved in compliance with existing zoning regulations while still preserving the natural tree canopy of Coconut Grove. The subject property is a 6,499SF lot where a 1,205 SF single-family residence was built in 1956. Current work items on the City’s iBuild portal list 2 living units comprised of a 2 story 6000 SF structure in its place. The removal of mature specimen trees goes directly against the intent of Chapter 17 of the City’s Tree Protection Ordinance. In this particular case, a design that preserves the specimen trees and canopy of Coconut Grove in harmony with the future structure is attainable. We request a permit to remove trees, especially the specimen oak located on the property be denied and construction be performed strict compliance with City codes and ordinances. Sincerely, Marcelo Fernandes, Chairman Coconut Grove Village Council www.CoconutGroveVC.org [email protected] 786-663-6511 OWNER NAME MAILING ADDRESS CITY 208 BIRD GROVE INVESTMENTS CORP 20851 SAN SIMEON WAY 205 NORTH MIAMI BEACH -

Wynwood Development Table of Contents 03 Project Overview

TOTAL AREA: 60,238 SQ.FT. Wynwood Development Table of Contents 03 Project Overview 15 Conceptual Drawings 17 Location 20 Demographics 23 Site Plan 26 Building Efficiency 29 RelatedISG Project Overview Project This featured property is centrally located in one of Miami’s hottest and trendiest neighborhood, Wynwood. The 60,238 SF site offers the unique possibility to develop one of South Florida’s most ground-breaking projects. There has only been a select amount of land deals in the past few years available in this neighborhood, and it is not common to find anything over 20,000 SF on average. With its desirable size and mixed use zoning, one can develop over 300 units with a retail component. Wynwood has experienced some of the highest rental rates of any area of South Florida, exceeding $3 per SF, and retail rates exceeding $100 SF. As the area continues to grow and evolve into a world renowned destination, it is forecasted that both residential and retail rental rates will keep increasing. Major landmark projects such as the Florida Brightline and Society Wynwood, as well as major groups such as Goldman Sachs, Zafra Bank, Thor Equity and Related Group investing here, it is positioned to keep growing at an unprecedented rate. Name Wynwood Development Style Development Site Location Edgewater - Miami 51 NE 22th Street Miami, FL 33137 Total Size 60,238 SQ. FT. (1.3829 ACRES) Lot A 50 NE 23nd STREET Folio # 01-3125-015-0140 Lot B 60 NE 23nd STREET Folio 01-3125-011-0330 Lot C 68 NE 23rd STREET Folio 01-3125-011-0320 Lot D 76 NE 23rd STREET Folio 01-3125-011-0310 Lot E 49 NE 23rd STREET Folio 01-3125-015-0140 Lot F 51 NE 23rd STREET Folio 01-3125-015-0130 Zoning T6-8-O URBAN CORE TRANSECT ZONE 04 Development Regulations And Area Requirements DEVELOPMENT REGULATIONS AND AREA REQUIREMENTS DESCRIPTION VALUE CODE SECTION REQUIRED PERMITTED PROVIDED CATEGORY RESIDENTIAL PERMITTED COMMERCIAL LODGING RESIDENTIAL COMMERCIAL LODGING RESIDENTIAL LODGING PERMITTED GENERAL COMMERCIAL PERMITTED LOT AREA / DENSITY MIN.5,000 SF LOT AREA MAX. -

Miami-Dade County Commission on Ethics and Public Trust

Biscayne Building 19 West Flagler Street Miami-Dade County Suite 220 Miami, Florida 33130 Commission on Ethics Phone: (305) 579-2594 Fax: (305) 579-2656 and Public Trust Memo To: Mike Murawski, independent ethics advocate Cc: Manny Diaz, ethics investigator From: Karl Ross, ethics investigator Date: Nov. 14, 2007 Re: K07-097, ABDA/ Allapattah Construction Inc. Investigative findings: Following the June 11, 2007, release of Audit No. 07-009 by the city of Miami’s Office of Independent Auditor General, COE reviewed the report for potential violations of the Miami-Dade ethics ordinance. This review prompted the opening of two ethics cases – one leading to a complaint against Mr. Sergio Rok for an apparent voting conflict – and the second ethics case captioned above involving Allapattah Construction Inc., a for-profit subsidiary of the Allapattah Business Development Authority. At issue is whether executives at ABDA including now Miami City Commissioner Angel Gonzalez improperly awarded a contract to Allapattah Construction in connection with federal affordable housing grants awarded through the city’s housing arm, the Department of Community Development. ABDA is a not-for-profit social services agency, and appeared to pay itself as much as $196,000 in profit and overhead in connection with the Ralph Plaza I and II projects, according to documents obtained from the auditor general. The city first awarded federal Home Investment Partnership Program (HOME) funds to ABDA on April 15, 1998, in the amount of $500,000 in connection with Ralph Plaza phase II. On Dec. 17, 2002, the city again awarded federal grant monies to ABDA in the amount of $730,000 in HOME funds for Ralph Plaza phase II. -

Metrorail/Coconut Grove Connection Study Phase II Technical

METRORAILICOCONUT GROVE CONNECTION STUDY DRAFT BACKGROUND RESEARCH Technical Memorandum Number 2 & TECHNICAL DATA DEVELOPMENT Technical Memorandum Number 3 Prepared for Prepared by IIStB Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive, Suite 200 Miami, Florida 33126 December 2004 METRORAIUCOCONUT GROVE CONNECTION STUDY DRAFT BACKGROUND RESEARCH Technical Memorandum Number 2 Prepared for Prepared by BS'R Reynolds, Smith and Hills, Inc. 6161 Blue Lagoon Drive, Suite 200 Miami, Florida 33126 December 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 2.0 STUDY DESCRiPTION ........................................................................................ 1 3.0 TRANSIT MODES DESCRIPTION ...................................................................... 4 3.1 ENHANCED BUS SERViCES ................................................................... 4 3.2 BUS RAPID TRANSIT .............................................................................. 5 3.3 TROLLEY BUS SERVICES ...................................................................... 6 3.4 SUSPENDED/CABLEWAY TRANSIT ...................................................... 7 3.5 AUTOMATED GUIDEWAY TRANSiT ....................................................... 7 3.6 LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT .............................................................................. 8 3.7 HEAVY RAIL ............................................................................................. 8 3.8 MONORAIL -

1200 Brickell Avenue, Miami, Florida 33131

Jonathan C. Lay, CCIM MSIRE MSF T 305 668 0620 www.FairchildPartners.com 1200 Brickell Avenue, Miami, Florida 33131 Senior Advisor | Commercial Real Estate Specialist [email protected] Licensed Real Estate Brokers AVAILABLE FOR SALE VIA TEN-X INCOME PRODUCING OFFICE CONDOMINIUM PORTFOLIO 1200 Brickell is located in the heart of Miami’s Financial District, and offers a unique opportunity to invest in prime commercial real estate in a gloabl city. Situated in the corner of Brickell Avenue and Coral Way, just blocks from Brickell City Centre, this $1.05 billion mixed-used development heightens the area’s level of urban living and sophistication. PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS DESCRIPTION • Common areas undergoing LED lighting retrofits LOCATION HIGHLIGHTS • 20- story, ± 231,501 SF • Upgraded fire panel • Located in Miami’s Financial District • Typical floor measures 11,730 SF • Direct access to I-95 • Parking ratio 2/1000 in adjacent parking garage AMENITIES • Within close proximity to Port Miami, American • Porte-cochere off of Brickell Avenue • Full service bank with ATM Airlines Arena, Downtown and South Beach • High-end finishes throughout the building • Morton’s Steakhouse • Closed proximity to Metromover station. • Lobby cafeteria BUILDING UPGRADES • 24/7 manned security & surveillance cameras • Renovated lobby and common areas • Remote access • New directory • On-site manager & building engineer • Upgraded elevator • Drop off lane on Brickell Avenue • Two new HVAC chillers SUITES #400 / #450 FLOOR PLAN SUITE SIZE (SF) OCCUPANCY 400 6,388 Vacant 425 2,432 Leased Month to Month 450 2,925 Leased Total 11,745 Brickell, one of Miami’s fastest-growing submarkets, ranks amongst the largest financial districts in the United States. -

Fact Sheet a New Landscaping Project

FACT SHEET A NEW LANDSCAPING PROJECT. WILL BEGIN IN YOUR AREA FIN# 405610-4-52-01 Begins: November 2013 OVERVIEW "Z.-o On Monday, November"H,-the Florida Department ofTransportation (FDOT) is scheduled to begin a landscaping maintenance project that extends along SR 972/Coral Way/SW 22 Street from SW 37 Avenue to SW 13 Avenue. WORK TO BE PERFORMED AFFECTED MUNICIPALITIES • La ndsca ping City of Mia mi, City of Coral Gables • Trimming trees • Removing damaged and dise"<lsed trees ESTIMATED CONSTRUCTION COST $150,000 , PROJECT SCHEDULE LANE CLOSURE AND DETOUR INFORMATION November 2013 - January 2014 Lane clo,sures will occur only during non-peak hours on non-event days/ nights/weekends. Non-peak hours are: • 9_00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. weekdays and weekends • 9:00 p .m. to 5:30 a.m. Su nday th rough Thursday nights • 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m, Friday and Saturday nights Submitted Intei the public record in connectiQn Viitn HELPFUL TIPS 1t'3,1ll n{j.,- on 11/2.1 II21 .: • Allow extra time to reach your destination Prjscill~ A. Thomp~ol1 • Obey all posted signs and speed limits , ,_ City"'Clerk • Watch for signs with information about upcoming work and traffic conditions ALWAYS PUT SAFETY FIRST For your safety and the safety of others, please use caution when driving, walking or biking around any construction zone. Wearing a safety belt is the single most effective way to protect people and reduce fatalities in motor vehicle crashes. The department takes steps to reduce construction effects, but you might experience the following around the work site; • Side street, traffic lane and sidewalk closures • Increased dust and noise • Workers and equipment moving around the area. -

Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs FY2019-20 Youth Arts Miami (YAM) Grant Award Recommendations

Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs FY2019-20 Youth Arts Miami (YAM) Grant Award Recommendations Grant #1 : - All Florida Youth Orchestra, Inc. dba Florida Youth Orchestra Award: Grant Amount 1708 N 40 AVE to be calculated based on Hollywood, Florida 33021 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support music education and outreach performances for 4,000 students, ages 5-18, at community sites and public venues in Miami-Dade County. Program activities will include orchestral training, violin/ percussion instruction for at-risk youth, family concerts for young children/seniors and outreach performances. Participants will engage in music education and benefit from improved musical skills and social/behavioral skills. Grant #2 : - Alliance for Musical Arts Productions, Inc. Award: Grant Amount 5020 NW 197 ST to be calculated based on Miami Gardens, Florida 33055 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support Alliance for Musical Arts' music programs for a total of 300 youth ages 7-18 and youth with disabilities up to age 22, at the Betty T. Ferguson Complex, in Miami Gardens. Youth Drum Line activities include classes in percussion and musical instrumentation. The “305” Community Band Camp, includes sight-reading, applied skill development, audition technique and rehearsals, two free performances open to the public, community performances, events, parades and demonstrations. Grant #3 : - American Children's Orchestras for Peace, Inc. Award: Grant Amount 2150 Coral Way #3-C to be calculated based on Miami, Florida 33145 YAM funding formula Funds are requested to support American Children's Orchestras for Peace for 800 students ages 5-13, at Jose Marti Park, Shenandoah Park and Shenandoah Elementary, in the City of Miami. -

FOR LEASE Sears | Coral Gables / Miami 3655 SW 22Nd Street, Miami, FL 33145

FOR LEASE Existing Sears Dept Store and Auto Center Located in CORAL GABLES 3655 SW 22nd Street Miami, FL 33145 MIRACLE MILE 37TH AVE JUSTIN BERRYMAN SENIOR DIRECTOR 305.755.4448 [email protected] CAROLINE CHENG DIRECTOR 305.755.4533 [email protected] CORAL WAY / SW 22ND STREET FOR LEASE Sears | Coral Gables / Miami 3655 SW 22nd Street, Miami, FL 33145 HIGHLIGHTS Sears stand-alone department store building and auto center available for lease. 42ND AVE SUBJECT *Tenant is currently open and operating, please DO PROPERTY 27,500 AADT SALZEDO ST SALZEDO NOT DISTURB MIRACLE MARKETPLACE Located at the signalized intersection of Coral GALIANO ST GALIANO PONCE DE LEON PONCE Way/SW 22nd St (36,000 AADT) and MIRACLE MILE RETAILERS 37th Avenue (27,500 AADT) at the eastern 37TH AVE 37TH entrance of Coral Gable’s Miracle Mile Downtown Coral Gables offers a unique shopping and entertainment destination in a SW 32ND AVE SW lushly landscaped environment of tree-lined streets including Miracle Mile, Giralda Plaza, and CORAL WAY / SW 22ND ST 36,000 AADT MIRACLE MILE Shops at Merrick Park Coral Gables is home to the University of Miami, ranked as the 2nd best college in Florida (18K students), 150+ multi-national corporations (11M SF office), and numerous local and international retailers and restaurants (2M SF retail) attracting over 3 million tourists annually DOUGLAS RD DOUGLAS THE PLAZA CORAL GABLES • 2.1M SF of Retail, JUSTIN BERRYMAN Office, and Residences SENIOR DIRECTOR • Delivery August 2022 305.755.4448 LE JEUNE RD [email protected]