Understanding Burnham's Vision and Chicago's Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHICAGO: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress

CHICAGO: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress A Guide and Resources to Build Chicago Progress into the 8th Grade Curriculum With Literacy and Critical Thinking Skills November 2009 Presenting sponsor for education Sponsor for eighth grade pilot program BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS “Our children must never lose their zeal for building a better world. They must not be discouraged from aspiring toward greatness, for they are to be the leaders of tomorrow.” Mary McLeod Bethune “Our children shall be taught that they are the coming responsible heads of their various communities.” Wacker Manual, 1911 Chicago, City of Possibilities, Plans, and Progress 2 More Resources: http://teacher.depaul.edu/ and http://burnhamplan100.uchicago.edu/ BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS Table of Contents Teacher Preview …………………………………………………………….4 Unit Plan …………………………………………………………………11 Part 1: Chicago, A History of Choices and Changes ……………………………13 Part 2: Your Community Today………………………………………………….37 Part 3: Plan for Community Progress…………………………………………….53 Part 4: The City Today……………………………………………………………69 Part 5: Bold Plans. Big Dreams. …………………………………………………79 Chicago, City of Possibilities, Plans, and Progress 3 More Resources: http://teacher.depaul.edu/ and http://burnhamplan100.uchicago.edu/ BOLD PLANS Chicago: City of Possibilities, Plans, Progress BIG DREAMS Note to Teachers A century ago, the bold vision of Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett’s The Plan of Chicago transformed 1909’s industrial city into the attractive global metropolis of today. The 100th anniversary of this plan gives us all an opportunity to examine both our city’s history and its future. The Centennial seeks to inspire current civic leaders to take full advantage of this moment in time to draw insights from Burnham’s comprehensive and forward-looking plan. -

LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014

THE LUCAS CULTURAL ARTS MUSEUM MAYOR’S TASK FORCE REPORT | CHICAGO May 16, 2014 Mayor Rahm Emanuel City Hall - 121 N LaSalle St. Chicago, IL 60602 Dear Mayor Emanuel, As co-chairs of the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum Site Selection Task Force, we are delighted to provide you with our report and recommendation for a site for the Lucas Cultural Arts Museum. The response from Chicagoans to this opportunity has been tremendous. After considering more than 50 sites, discussing comments from our public forum and website, reviewing input from more than 300 students, and examining data from myriad sources, we are thrilled to recommend a site we believe not only meets the criteria you set out but also goes beyond to position the Museum as a new jewel in Chicago’s crown of iconic sites. Our recommendation offers to transform existing parking lots into a place where students, families, residents, and visitors from around our region and across the globe can learn together, enjoy nature, and be inspired. Speaking for all Task Force members, we were both honored to be asked to serve on this Task Force and a bit awed by your charge to us. The vision set forth by George Lucas is bold, and the stakes for Chicago are equally high. Chicago has a unique combination of attributes that sets it apart from other cities—a history of cultural vitality and groundbreaking arts, a tradition of achieving goals that once seemed impossible, a legacy of coming together around grand opportunities, and not least of all, a setting unrivaled in its natural and man-made beauty. -

To Lead and Inspire Philanthropic Efforts That Measurably Improve the Quality of Life and the Prosperity of Our Region

2008 ANNUAL REPORT To lead and inspire philanthropic efforts that measurably improve the quality of life and the prosperity of our region. OUR VALUES Five values define our promise to the individuals and communities we serve: INTEGRITY Our responsibility, first and foremost, is to uphold the public trust placed in us and to ensure that we emulate the highest ethical standards, honor our commitments, remain objective and transparent and respect all of our stakeholders. STEWARDSHIP & SERVICE We endeavor to provide the highest level of service and due diligence to our donors and grant recipients and to safeguard donor intent in perpetuity. DIVERSITY & INCLUSION Our strength is found in our differences and we strive to integrate diversity in all that we do. COLLABORATION We value the transformative power of partnerships based on mutual interests, trust and respect and we work in concert with those who are similarly dedicated to improving our community. INNOVATION We seek and stimulate new approaches to address what matters most to the people and we serve, as well as support, others who do likewise in our shared commitment to improve metropolitan Chicago. OUR VISION The Chicago Community Trust is committed to: • Maximizing our community and donor impact through strategic grant making and bold leadership; • Accelerating our asset growth by attracting new donors and creating a closer relationship with existing donors; • Delivering operational excellence to our donors, grant recipients and staff members. In 2008, The Chicago Community Trust addressed the foreclosure crisis by spearheading an action plan with over 100 experts from 70 nonprofit, private and public organizations. -

2017 Annual Report

THE CIVIC FEDERATION 2017 ANNUAL REPORT research • information • action since 1894 2017 THE CIVIC FEDERATION’S MISSION To provide research, analysis and recommendations that: • Champion efficient delivery of high-quality government services; • Promote sustainable tax policies and responsible long-term planning; • Improve government transparency and accountability; and • Educate and serve as a resource for policymakers, opinion leaders and the broader public. THE CIVIC FEDERATION’S HISTORY from our The Civic Federation was founded in 1894 by several of Chicago’s most prominent citizens, including Jane Addams, Bertha Honoré Palmer and Lyman J. Gage. They chairman coalesced around the need to address deep concerns about the city’s economic, political and moral climate at the end of the 19th century. The Federation has since and become a leading advocate for efficient delivery of public services and sustainable president tax policies. 2017 CIVIC FEDERATION STAFF Today the work of the Federation continues to evolve as greater emphasis is placed on working with government officials to improve the efficiency, effectiveness and accountability of the State of Illinois and local governments. The Civic Federation’s The State of Illinois’ enactment of a comprehensive fiscal Lauracyn Abdullah Institute for Illinois’ Fiscal Sustainability was launched in 2008 to provide Illinois Director of Finance and Operations policymakers, the media and the general public with timely and comprehensive year 2018 budget in July 2017 gave taxpayers reason to Patricia Acosta analysis of the state budget and other fiscal proposals for the State of Illinois. Executive Assistant breathe a short sigh of relief as Illinois finally joined the 49 Katy Broom Communications Director other states in abiding by the most basic of financial tenets. -

Chicago Chapter Newsletter

Chicago Chapter Newsletter 205 W. WACKER DRIVE, CHICAGO, IL 312 - 6 1 6 - 9400 WEBSITE: WWW.CCAI.ORG December 2013 Message from 2013 CCAI President Paul Gillespie, MAI Dear Chicago Chapter Colleagues, IN THIS ISSUE: Congratulations to all 33 of our Chapter Members who earned their designations in 2013, and especially those who earned their initials in just the past month: Megan Czechowski, MAI PRESIDENT PAUL 1 GILLESPIE Thomas Griffith, MAI Ellen Nord, SRA NEWLY DESIGNATED 2 Richard DeVerdier, MAI, SRA MEMBERS Joe Webster, MAI MADIGAN LUNCHEON 3 A special welcome to the nearly 40 new affiliates who joined the Chicago Chapter in 2013! CHIEF APPRAISER PANEL 6 Thank you to all of the members who worked on the gatherings in downtown & suburban Chicago, Bloom- WALKING TOUR 6 ington, Champaign, East Peoria, and even at AI Connect in Indianapolis. KAYAKING CHICAGO 7 Looking back at the first issue of The Appraisal Journal, you’ll find a letter from then-Institute President, LA 25TH ANNIVERSARY 9 Mr. Philip Kniskern, dated August 1, 1932, in which he states: REAL ESTATE FALLACIES 16 ”…the Institute can be only as strong as its component parts and that each member in joining it has as- WHY WE’LL OVERBUILD 16 sumed a duty to the Institute and to the public to take an active, aggressive interest in its activities and AGAIN—RACHEL WEBER purposes. The greater the strength of the Institute the greater will be its selfish value to its members. It has FARM LAND BUBBLE 19 the opportunity of doing a much needed and valuable public work while producing monetary benefits to its INSTALLATION DINNER 19 members.” UPCOMING EDUCATION 33 Colleagues, 82-years later, isn’t this all still true today? UPCOMING EVENTS 35 Become actively involved in your nearly state-wide Chicago Chapter, in your Appraisal Institute and Illinois JOB OPPORTUNITIES 36 Coalition of Appraisal Professionals. -

No Small Plans: Celebrating GO to 2040, Chicago’S First Major Regional Blueprint Since Burnham | Newcity

No Small Plans: Celebrating GO TO 2040, Chicago’s first major regional blueprint since Burnham | Newcity Home About Newcity Fall Preview 2010 Street Smart Chicago Oct No Small Plans: Celebrating GO TO 2040, Chicago’s first Newcity Sites 19 major regional blueprint since Burnham Best of Chicago Chicago History, Media, Politics Add comments Booze Muse Boutiqueville It’s pouring, but that doesn’t dampen the spirits of a thousand sharply-dressed politicians, urban planners and Chicago Weekly other civic leaders crammed into a tent on top of Newcity Art Millennium Park’s Harris Theater. They’re here to launch Newcity Film GO TO 2040, a blueprint for making tough development Newcity Lit and spending choices in the Chicago area’s 284 communities, for the next few decades and beyond. Newcity Music Newcity Resto The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) will Newcity Stage lead the implementation process, and stakes are high. As Newcity Summer the region’s population balloons from its current 8.6 million to an estimated 11 million by 2040, the decisions we make now will determine whether the Chicago area becomes Categories more prosperous, green and equitable or devolves into a -Neighborhood/Suburb (106) depressed, grid-locked, smog-choked dystopia. Andersonville (2) Austin (1) The plan, developed by CMAP and its partner organizations Avondale (1) over three years and drawing on feedback from more than Beverly (1) 35,000 residents, includes the four themes of Livable Communities, Human Capital, Efficient Governance and Regional Mobility. It makes detailed recommendations for facing challenges like job Bridgeport (2) creation, preserving the environment, housing and transportation. -

Charter Reform in Chicago, 1890-1915: Community and Government in the Progressive Era

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1980 Charter Reform in Chicago, 1890-1915: Community and Government in the Progressive Era Maureen A. Flanagan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Flanagan, Maureen A., "Charter Reform in Chicago, 1890-1915: Community and Government in the Progressive Era" (1980). Dissertations. 1998. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1998 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1980 Maureen A. Flanagan CHARTER REFORM IN CHICAGO, 1890-1915: COMMUNITY AND GOVERNMENT IN THE PRCGRESSIVE ERA by Maureen Anne Flanagan A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 1980 ACKNOWlEDGMENTS I take this opportunity to thank several persons who offered guidance, encouragement, and stimulation in the research and writing of this dissertation. Professor James Penick gave me the latitude to pursue my research and develop my ideas in ways that were impor tant to me, while ahlays helping me understand the larger historical context of my work. Professor William Galush offered much guidance and insight into the study of ethnic groups in the city. And Pro fessor Lew Erenberg constantly prodded me to explore and develop the important ideas, and offered constant moral support. -

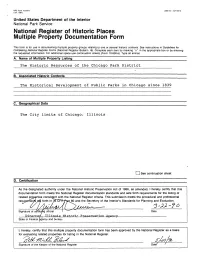

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No W24-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________________________ The Historic Resources of the Chicago Park District B. Associated Historic Contexts The Historical Development of Public Parks in Chicago since 1839 C. Geographical Data The City limits of Chicago/ Illinois I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional reqt-jjjjetfienis a& forth in 36^Cr-H"Pact60^ and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date ___ Director , T1 1 1nnls State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. _________________ Signature of the Keeper of the National Register Date E. Statement of Historic Contexts Discuss each historic context listed in Section B. -

After the Towers: the Destruction of Public Housing and the Remaking

After the Towers: The Destruction of Public Housing and the Remaking of Chicago by Andrea Field A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved March 2017 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Philip Vandermeer, Chair Deirdre Pfeiffer Victoria Thompson ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2017 ©2017 Andrea Field All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the history of Cabrini-Green through the lens of placemaking. Cabrini-Green was one of the nation's most notorious public housing developments, known for sensational murders of police officers and children, and broadcast to the nation as a place to be avoided. Understanding Cabrini-Green as a place also requires appreciation for how residents created and defended their community. These two visions—Cabrini-Green as a primary example of a failed public housing program and architecture and Cabrini-Green as a place people called home—clashed throughout the site's history, but came into focus with its planned demolition in the Chicago Housing Authority's Plan for Transformation. Demolition and reconstruction of Cabrini-Green was supposed to create a model for public housing renewal in Chicago. But residents feared that this was simply an effort to remove them from valuable land on Chicago's Near North Side and deprive them of new neighborhood improvements. The imminent destruction of the CHA’s high-rises uncovered desires to commemorate the public housing developments like Cabrini-Green and the people who lived there through a variety of public history and public art projects. This dissertation explores place from multiple perspectives including architecture, city planning, neighborhood development, and public and oral history. -

A Look Back on Eight Years of Progress

MOVING CHICAGO FORWARD: A LOOK BACK ON EIGHT YEARS OF PROGRESS MAYOR RAHM EMANUEL MOVING CHICAGO FORWARD • A LOOK BACK ON EIGHT YEARS OF PROGRESS LETTER FROM THE MAYOR May 2, 2019 Dear Fellow Chicagoans, It has been the honor of my lifetime to serve the people of this great city as mayor for eight years. Together, we have addressed longstanding challenges, overcome old obstacles and confronted new headwinds. At the outset of my administration, Chicago was beset by fiscal, economic and academic crises. Many thought our best days were behind us, and that the ingenuity and ability to rise to meet great challenges that had defined our city for generations was part of our past, but not our future. In response, Chicagoans came together and showed the resolve and resilience that define the character of this great city. Today, Chicago’s fiscal health is stronger than it has been in many years, with a smaller structural deficit, a larger rainy day fund, true and honest accounting of city finances, and dedicated recurring revenues for all four city pension funds. Our economic landscape is dramatically improved, with historic lows in unemployment, the highest level of jobs per-capita in the city in over five decades, and a record amount of corporate relocations and foreign direct investment. Academically, Chicago’s students are raising the bar for success and making our city proud. Every year for the past seven, a new record number of Chicago’s students have graduated high school. More graduates than ever now go to college. Stanford University found CPS students are learning faster than 96 percent of students of all districts in the United States. -

The Role of Selected Women in Education and Child Related Reform Programs in Chicago: 1871-1917

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1995 The Role of Selected Women in Education and Child Related Reform Programs in Chicago: 1871-1917 Kenneth M. Dooley Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Dooley, Kenneth M., "The Role of Selected Women in Education and Child Related Reform Programs in Chicago: 1871-1917" (1995). Dissertations. 3587. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3587 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1995 Kenneth M. Dooley LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE ROLE OF SELECTED WOMEN IN EDUCATION AND CHILD RELATED REFORM PROGRAMS IN CHICAGO: 1871-1917 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP AND POLICY STUDIES BY KENNETH M. DOOLEY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1996 @copyright by Kenneth M. Dooley, 1995 All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS What we are is at least in part a result of all of our experiences. I have been quite fortunate to have studied with some quite excellent teachers, teachers that encouraged me and challenged me. Teachers that brought me knowledge, and taught me how to find it for myself, teachers too numerous to mention here. -

The Civic Federation Annual Report 2018

THE CIVIC FEDERATION ANNUAL REPORT 2018 RESEARCH | INFORMATION | ACTION Since 1894 MISSION To provide research, analysis and recommendations that: • Champion efficient delivery of high-quality government services; • Promote sustainable tax policies and responsible long-term planning; • Improve government transparency and accountability; and • Educate and serve as a resource for policymakers, opinion leaders and the broader public. HISTORY FROM OUR CHAIR AND PRESIDENT The Civic Federation was founded in 1894 by several of Chicago’s most As both the State of Illinois and the City Representing the region’s major prominent citizens, including Jane Addams, Bertha Honoré Palmer and Lyman of Chicago welcome new leadership, corporations, service firms and J. Gage. They coalesced around the need to address deep concerns about the the Civic Federation has been called on institutions, our Trustees, Board and city’s economic, political and moral climate at the end of the 19th century. The more than ever by elected officials, civic Council remain committed to effecting Federation has since become a leading advocate for efficient delivery of public and community groups and the media positive change. At Board and committee services and sustainable tax policies. to provide context and perspective on meetings, members engage in rigorous the many financial and governance policy debate, work to affirm the Today the work of the Federation continues to evolve as greater emphasis challenges facing our region. Federation’s principles and vet staff research and analysis. These efforts are is placed on working with government officials to improve the efficiency, As always, this includes publication effectiveness and accountability of the State of Illinois and local governments.