You Should) Take It with You

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 21 May 2016

Philippa H Deeley Ltd Catalogue 21 May 2016 1 A Victorian Staffordshire pottery flatback figural 16 A Staffordshire pottery flatback group of a seated group of Queen Victoria and King Victor lion with a Greek warrior on his back and a boy Emmanuel II of Sardinia, c1860, titled 'Queen and beside him with a bow, 39cm high £30.00 - £50.00 King of Sardinia', to the base, 34.5cm high £50.00 - 17 A Victorian Staffordshire pottery flatback figure of £60.00 the Prince of Wales with a dog, titled to the base, 2 A Victorian Staffordshire pottery figure of Will 37cm high £30.00 - £40.00 Watch, the notorious smuggler and privateer, 18 A Victorian Staffordshire flatback group of a girl on holding a pistol in each hand, titled to the base, a pony, 22cm high and another Staffordshire 32.5cm high £40.00 - £60.00 flatback group of a lady riding in a carriage behind 3 A Victorian Staffordshire pottery flatback figural a rearing horse, 22.5cm high £40.00 - £60.00 group of King John signing the Magna Carta in a 19 A Stafforshire pottery flatback pocket watch stand tent flanked by two children, 30.5cm high £50.00 - in the form of three Scottish ladies dancing, 27cm £70.00 high and two smaller groups of two Scottish girls 4 A Victorian Staffordshire pottery figure of Queen dancing, 14.5cm high and a drummer boy, his Victoria seated upon her throne, 19cm high, and a sweetheart and a rabbit, 16cm high £30.00 - smaller figure of Prince Albert in a similar pose, £40.00 13.5cm high £50.00 - £70.00 20 Three Staffordshire pottery flatback pastille 5 A pair of Staffordshire -

The American Ceramic Society 25Th International Congress On

The American Ceramic Society 25th International Congress on Glass (ICG 2019) ABSTRACT BOOK June 9–14, 2019 Boston, Massachusetts USA Introduction This volume contains abstracts for over 900 presentations during the 2019 Conference on International Commission on Glass Meeting (ICG 2019) in Boston, Massachusetts. The abstracts are reproduced as submitted by authors, a format that provides for longer, more detailed descriptions of papers. The American Ceramic Society accepts no responsibility for the content or quality of the abstract content. Abstracts are arranged by day, then by symposium and session title. An Author Index appears at the back of this book. The Meeting Guide contains locations of sessions with times, titles and authors of papers, but not presentation abstracts. How to Use the Abstract Book Refer to the Table of Contents to determine page numbers on which specific session abstracts begin. At the beginning of each session are headings that list session title, location and session chair. Starting times for presentations and paper numbers precede each paper title. The Author Index lists each author and the page number on which their abstract can be found. Copyright © 2019 The American Ceramic Society (www.ceramics.org). All rights reserved. MEETING REGULATIONS The American Ceramic Society is a nonprofit scientific organization that facilitates whether in print, electronic or other media, including The American Ceramic Society’s the exchange of knowledge meetings and publication of papers for future reference. website. By participating in the conference, you grant The American Ceramic Society The Society owns and retains full right to control its publications and its meetings. -

The Magical World of Snow Globes

Anthony Wayne appointment George Ohr pottery ‘going crazy’ among Pook highlights at Keramics auction $1.50 National p. 1 National p. 1 AntiqueWeekHE EEKLY N T IQUE A UC T ION & C OLLEC T ING N E W SP A PER T W A C EN T R A L E DI T ION VOL. 52 ISSUE NO. 2624 www.antiqueweek.com JANUARY 13, 2020 The magical world of snow globes By Melody Amsel-Arieli Since middle and upper class families enjoyed collecting and displaying decorative objects on their desks and mantel places, small snow globe workshops also sprang up Snow globes, small, perfect worlds, known too as water domes., snow domes, and in Germany, France, Czechoslovakia, and Poland. Americans traveling abroad prized blizzard weights, resemble glass-domed paperweights. Their transparent water- them as distinctive, portable souvenirs. filled orbs, containing tiny figurines fashioned from porcelain, bone, metal, European snow globes crossed the Atlantic in the 1920s. Soon after, minerals, wax, or rubber, are infused with ethereal snow-like flakes. Joseph Garaja of Pittsburgh, Pa., patented a prototype featuring a When shaken, then replaced upright, these tiny bits flutter gently fish swimming through river reeds. Once in production, addition- toward a wood, ceramic, or stone base. al patents followed, offering an array of similar, inexpensive, To some, snow globes are nostalgic childhood trinkets, cher- mass-produced models. By the late 1930s, Japanese-made ished keepsakes, cheerful holiday staples, winter wonderlands. models also reached the American market. To others, they are fascinating reflections of the cultures that Soon snow globes were found everywhere. -

Vitreous Enamel: Mycenæan Period Jewelry to First Period Chemistry

Vitreous Enamel: Mycenæan Period Jewelry to First Period Chemistry Date : 17/10/2018 More durable than glass and just as beautiful, vitreous enamel, also known as porcelain enamel, offers a non-porous, glass-like finish created by fusing finely ground colored glass to a substrate through a firing process. Adding to its strength and durability, the substrate used is always a metal, whether precious or non-precious, for its stability and capacity to withstand the firing process. Origins It is unknown who first developed enamelling and when the process was first used, but the most historic enameled artifacts were discovered in Cyprus in the 1950s dating as far back as the 13th Century BC. Scientists have determined the set of six rings and an enameled golden scepter found belonged to the craftspeople of Mycenaean Greece. Enamelling Evolution Metalsmiths first used enamel to take the place of gems in their work, and this was the earliest example of “paste stones,” a common element in both precious and costume jewelry today. In © 2019 PolyVision. is the leading manufacturer of CeramicSteel surfaces for use in whiteboards, chalkboards and an array of architectural applications. Page 1 of 6 this technique, enamel is placed in channels set that have been soldered to the metal. Meaning “divided into cells,” Cloisonné refers to this earliest practiced enameling technique. Champlevé, or raised fields, differs from Cloisonné in the way the space for the enamel is created. Unlike Cloisonné, the Champlevé technique requires carving away the substrate instead of setting forms onto the metal base for the enamel to fill. -

Glass and Glass-Ceramics

Chapter 3 Sintering and Microstructure of Ceramics 3.1. Sintering and microstructure of ceramics We saw in Chapter 1 that sintering is at the heart of ceramic processes. However, as sintering takes place only in the last of the three main stages of the process (powders o forming o heat treatments), one might be surprised to see that the place devoted to it in written works is much greater than that devoted to powder preparation and forming stages. This is perhaps because sintering involves scientific considerations more directly, whereas the other two stages often stress more technical observations M in the best possible meaning of the term, but with manufacturing secrets and industrial property aspects that are not compatible with the dissemination of knowledge. However, there is more: being the last of the three stages M even though it may be followed by various finishing treatments (rectification, decoration, deposit of surfacing coatings, etc.) M sintering often reveals defects caused during the preceding stages, which are generally optimized with respect to sintering, which perfects them M for example, the granularity of the powders directly impacts on the densification and grain growth, so therefore the success of the powder treatment is validated by the performances of the sintered part. Sintering allows the consolidation M the non-cohesive granular medium becomes a cohesive material M whilst organizing the microstructure (size and shape of the grains, rate and nature of the porosity, etc.). However, the microstructure determines to a large extent the performances of the material: all the more reason why sintering Chapter written by Philippe BOCH and Anne LERICHE. -

Stronger-Than-Glass

LIQ Fusion 7000 FBE™ . A Stronger System Than Glass! LIQ Fusion 7000 FBE™ technology is here! In bolted storage tanks, Tank Connection offers the next generation of unmatched coating performance. LIQ Fusion 7000 FBE™ is designed as the replacement for glass/porcelain enamel coatings. Once you compare the facts on each system, you will find that Tank Connection’s LIQ Fusion 7000 FBE™ coating system is a stronger system than glass: LIQ Fusion 7000 FBE™ – Lab Testing* Glass/Vitreous Enamel – Lab Testing* Bolted sidewall panel Excellent (with exception of panel edges Excellent protection and bolt holes) Poor, as shipped from the factory Edge protection Excellent, coated LIQ Fusion FBE™ (covered with mastic sealant in the field) Poor, as shipped from the factory Bolt holes Excellent, coated LIQ Fusion FBE™ (covered with mastic sealant in the field) 8-13 mils (must be verified due to high Coating Thickness 7-11 mils shop defect rate) 3-14 (depending on product 3-11 (depending on product pH and temperature) and temperature) Corrosion Resistance Excellent Excellent (ASTM B-117) Temperature 200º F water, Dry 300º F 140º F water, Dry N/A Tolerance LIQ Fusion FBE™ (advanced fusion Coating to substrate Glass /vitreous enamel technology bond technology) Flexibility Passes 1/8” mandrel test None (cannot be field repaired) Impact 160 in/lbs 4 in/lbs History New technology with 5-7 years testing Old technology with history of spalling Salt Spray Passes 7500 hours Passes 7500 hours Submerged structural components are Submerged structural components are Liquids coated with LIQ Fusion FBE™ galvanized Holiday Free Yes No Coating Required (due to uncoated edges and Cathodic protection Not required bolt holes) Sealant Mastic Mastic Panel Size ~ 5’ tall x 10’ long ~ 4.5’ tall x 9’ long Construction Type Horizontal RTP (rolled, tapered panel) Horizontal RTP (rolled, tapered panel) *Note: Production panels (not lab panels) were utilized for testing. -

U046en Steel Sheets for Vitreous Enameling

www.nipponsteel.com Steel Sheet Steel Sheets for Vitreous Enameling SteelSteel Sheets Sheets for for Vitreous Vitreous Enameling Enameling 2-6-1 Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku,Tokyo 100-8071 Japan U046en_02_202004pU046en_02_202004f Tel: +81-3-6867-4111 © 2019, 2020 NIPPON STEEL CORPORATION NIPPON STEEL's Introduction Steel Sheets for Vitreous Enameling Manufacturing Processes Vitreous enamel is made by coating metal surface with glass. The compound material com- Table of Contents bines the properties of metal, such as high strength and excellent workability, with the char- Introduction acteristics of glass, such as corrosion resistance, chemical resistance, wear resistance, and Manufacturing Processes 1 visual appeal. Vitreous enamel has a long history, and the origin of industrial vitreous enamel- In addition to the high strength and excellent workability of cold-rolled steel sheets, steel sheets for vitreous enameling need to satisfy addi- ing is said to date back to the 17th century. Features 2 tional customer requirements such as higher adhesion strength of vitreous enamel, higher fishscaling resistance, and better enamel finish. Vitreous enamel is applied to not only kitchen utensils like pots, kettles and bathtubs but all- Product Performance 3 For this reason, in manufacturing steel sheets for vitreous enameling, the composition of the molten metal is controlled to an optimum level so containers used in the chemical and medical fields, sanitary wares, chemical machineries, and decarburized in the secondary refining process, and the temperature of the steel strip is precisely controlled in the hot rolling process Examples of Applications 4 building materials, and various components used in the energy field (such as heat exchanger and the continuous annealing process. -

Storage Tanks for Water and Wastewater 2016 R2.Pub

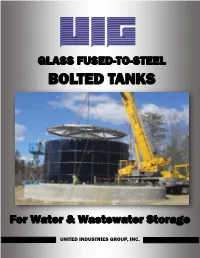

GLASS FUSED-TO-STEEL BOLTED TANKS For Water & Wastewater Storage UNITED INDUSTRIES GROUP, INC. UIG ETRCS Tanks DESIGN AND ENGINEERING SEPARATING FACT from FICTION UIG Bolted Tanks provide years of low cost storage because of their special design and construction. Vitreous or Porcelain enamel, is a material made by fusing powdered glass to a substrate by firing. UIG Tanks are designed by engineers with decades The powder melts, flows, and then hardens to a of experience in devising storage tanks for all types smooth, durable vitreous coating on metal. It is an of liquids and uses in the water and wastewater integrated layered composite of glass and metal. industry. UIG, Inc. utilizes those standards, Since the 19th century the term applies to industrial specifications and/or interpretations and materials and many metal consumer objects. recommendations of professionally recognized agencies and groups such as AWWA D-103, API 12B, ACI, AISI, AWS, ASTM, Vitreous enamel can be applied to most metals. BS, NFPA, DIN, UL, ISO, FM, U.S. Government, Modern industrial enamel is applied to steel in UIG, etc. as the basis in establishing its own which the carbon content is controlled to prevent design, fabrications and quality criteria, unwanted reactions at the firing temperatures. practices methods and tolerances. Utilizing our UIG’s Enameled Titanium Rich Carbon Steel advanced operations, tanks for special conditions (ETRCS) panels go a step further by utilizing a such as heavy liquids, high wind factors, snow or unique quality of steel with a high titanium seismic loadings can be designed for maximum content. efficiency, long-life and service. -

HO121113 Sale

For Sale by Auction to be held at Dowell Street, Honiton EX14 1LX Tel: 01404 510000 th TUESDAY 12 NOVEMBER 2013 Silver, Silver Plate, Jewellery, Ceramics, Glass & Oriental, Works of Art, Collectables, Pictures, Furniture yeer SALE COMMENCES AT 10.00am SALE REFERENCE HO79 Catalogue £1.50 Buyers are reminded to check the ‘Saleroom Notice’ for information regarding WITHDRAWN LOTS and EXTRA LOTS Order of Sale: On View: Silver & Silver Plate 1 - 163 Saturday 9th November 9.00am – 12noon Jewellery 200 - 400 Monday 11th November 9.00am – 7.00pm Ceramics, Glass & Oriental 401 - 510 Morning of Sale from 9.00am Works of Art, Collectables 511 - 620 Pictures 626 - 660 Furniture 661 - 895 W: www.bhandl.co.uk E: [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @BHandL IMPORTANT NOTICE From December 2013 all sales will be conducted from the South West of England Centre of Auction Excellence in Okehampton Street, Exeter The last auction to be held in Honiton, Dowell Street will be on 10th December 2013. All purchased goods must be collected by Friday 13th December. After this date ALL GOODS will be sent to commercial storage and charges will be applied. Tuesday 12th November 2013 Sale commences at 10am SILVER AND SILVER PLATE 1 . A 19th century plated coffee 6 . A set of six silver Old English pot of urn form with stylised pattern teaspoons, maker CJV foliate engraved banding, Ltd, London, 1961, 3.5ozs. (6) wooden handle, 30cm high. 7 . A cased set of six silver stump 2 . An electroplated tea kettle, top coffee spoons, maker stand and lamp, of an oval half WHH, Birmingham, 1933/34, fluted form, 24cm high. -

Quirk Brochure #1

TWO-DAY On Tuesday, August 24th at 10 AM CDT Location: 1351 Briarwoods Lane, Owensboro, KY. (Forest Hills Subdivision) From HWY 231 at Daviess County High School head southwest for .5 miles and turn west on Hickory Lane, then bare left on Briarwood. Watch for signs! Since I have moved, I have authorized Kurtz Auction and Realty to sell the following regardless of price: ANTIQUES - PRIMITIVES - MILITARIA COLLECTIBLES & MORE Day 1 SEE REVERSE SIDE FOR DETAILS ON HOME, CAR & FURNITURE Antiques & Primitives: Owensboro Wagon tin advertising, Owensboro tobacco basket, Boye Brand needle dispenser, stoneware crocks, samplers, pottery, large collection of Fostoria, Wedgewood lusterglass, Ironstone, copper, brass, Toby mugs, cranberry glass, cast iron, Yellow ware, McCoy bowls and pottery, Uranium glass Bavari- an glass, cookie cutters, baskets, primitive boxes, quilts, ephemera, collar box, dresser sets, sterling silver mirror, shaving mugs, hobnail, Alladin lamps, costume jewelry, mirrors, silver plate, sterling silver, coin silver, medicine bottles, fountain pens, engineering and drafting tools, marbles, lusters, chandelier crystals and parts, (3) Victorian hanging gas lights (electrified), lamps, linens, ladies change purses, Victorian ladies fashion prints, books, primitive kitchen ware, rolling pins, wire baskets, firkins, pantry boxes, dough bowls, Evansville phone books, Calhoun year- books, Virginia Tech yearbook, 33 records, radio transcription discs, Virginia Tech station break recordings; radios & signal generators, cameras, ambrotype photos in leather cases, lustre jugs, Majolica cheese dome, toleware, needlepoint covers, canning jars, medicine bottles, stoneware ink bottles, stoneware liquor bottles, large collec- tion of Pfaltzgraf, bread box, small foot stools, shelves, small wagon and more. Militaria: H&R .22 pistol, WWII German Army Officers dagger with hanger and knots, army dagger, misc. -

Uranium Glass in Museum Collections

UNIVERSIDADE NOVA DE LISBOA Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Departamento de Conservação e Restauro Uranium Glass in Museum Collections Filipa Mendes da Ponte Lopes Dissertação apresentada na Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Conservação e Restauro. Área de especialização – Vidro Orientação: Professor Doutor António Pires de Matos (ITN, FCT-UNL) Lisboa Julho 2008 Acknowledgments This thesis was possible due to the invaluable support and contributions of Dr António Pires de Matos, Dr Andreia Ruivo, Dr Augusta Lima and Dr Vânia Muralha from VICARTE – “Vidro e Cerâmica para as Artes”. I am also especially grateful to Radiological Protection Department from Instituto Tecnológico e Nuclear. I wish to thank José Luís Liberato for his technical assistance. 2 Vidro de Urânio em Colecções Museológicas Filipa Lopes Sumário A presença de vidros de urânio em colecções museológicas e privadas tem vindo a suscitar preocupações na área da protecção radiológica relativamente à possibilidade de exposição à radiação ionizante emitida por este tipo de objectos. Foram estudados catorze objectos de vidro com diferentes concentrações de óxido de urânio. A determinação da dose de radiação β/γ foi efectuada com um detector β/γ colocado a diferentes distâncias dos objectos de vidro. Na maioria dos objectos, a dose de radiação não é preocupante, se algumas precauções forem tidas em conta. O radão 226 (226Rn), usualmente o radionuclido que mais contribui para a totalidade da dose de exposição natural, e que resulta do decaimento do rádio 226 (226Ra) nas séries do urânio natural, foi também determinado e os valores obtidos encontram-se próximos dos valores do fundo. -

Text Catalogue

Page 1 Lot No. Description Lot No. Description Lot No. Description 1 Bay of Stereos 38 Bay of Red Bull Energy Drinks 76 Hand Painted Australian Platter, Cup & Saucer, etc 2 Sewing Machine, Dolls House, etc 39 Bay of Assorted End of Run Mixed Drinks 77 Retro Cannister Set 3 Bay of Boxed Dinnerware 40 Bay of Assorted End of Run Beers 78 Retro Cannister Set 4 Bay of Sundries 41 Bay of Assorted Wines 79 Two Dial Phones 5 Bay of China & Glassware 42 Bay of Assorted End of Run Mixed Drinks 80 Two Model Cars 6 Quantity of Table Lamps 43 Bay of Assorted End of Run Beers 81 Assorted Shells 7 Bosch Hedge Trimmer & Icon Chainsaw 44 Bay of Fever Tree Lemonade & Tonic 82 Bay of Collectables 8 Bay of Electrical 45 Bay of Assorted Cask Wine 83 Bay of China, etc 9 Bay of Assorted Sundries 46 Bay of Assorted End of Run Beers 84 Drink Sets 10 Bay of Tools 47 Bay of Assorted End of Run Beers 85 Cast Scales & Weights 11 Bay of Assorted Tools 48 Bay of Assorted Wines 86 Lego Sets, etc 12 Bay of Vintage Car Sundries, Rustic Sundries, etc 49 Bay of Assorted Cask Wine 87 Quantity of China 13 Bay of Assorted Sundries 50 Sanyo Vintage Stereo 88 Box of CD's & Quantity of Records 14 Two Lamps 51 Agilent WireScope 350 Network Tester 89 Oriental Plates & Vase 15 Carton of 24 x 500ml Swiss Hand Care Hand Sanitizer 52 Workzone Titanium Belt & Disk Sasnder 90 Wooden Boxes, etc 16 Bay of Assorted Sundries 53 6 x Bottles of Bickfords Lime Cordial 91 Quantity of Assorted Comics 17 Bay of Tools 54 Two Hot Pots & Buddha Figure 92 Enamel Cookware 18 Bay of Sundries 55 Three