Foreign Influence in Ancient India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Surveys in Lower Sindh: Preliminary Results of the 2009 Season

Journal of Asian Civilizations -1- Archaeological Surveys in Lower Sindh: Preliminary Results of the 2009 Season Paolo Biagi ABSTRACT In January-February 2009 archaeological surveys were conducted in three different regions of Lower Sindh, from Ranikot, in the north, to the Makli Hills, in the south. They resulted in the discovery of many sites and flint spots within a territory the archaeology of which was previously poorly known. This paper is aimed at the description of these finds, their cultural attribution and, whenever possible, absolute chronology. Particular attention has been paid to the radiocarbon chronology of the sites located on the rocky outcrops that rise from the alluvial plain of the Indus delta, a few of which indicate that seafaring along the northern shores of the Arabian Sea was already active at least since the very beginning of the seventh millennium uncal BP. 1. PREFACE This paper is a preliminary report of the surveys carried out in January and February 2009 in Lower Sindh, between Ranikot, in the north, and the Makli Hills, in the south. The scope of the surveys, which were part of a joint venture by Ca’ Foscari University, Venice (I) and Sindh University, Jamshoro (PK), was to discover new archaeological sites in a territory insufficiently explored, and define their cultural attribution and absolute chronology by radiocarbon dating. Although some parts of the above region had already been surveyed by other authors (see, for instance, MAJUMDAR, 1934; COUSENS, 1998; FRANKE-VOGT, 1999; FLAM, 2006), our attention focused mainly on territories never accurately investigated before. The surveys were conducted by systematic walking in the three main, well- defined areas described in the following chapters (fig. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Asteroid Shape and Spin Statistics from Convex Models J

Asteroid shape and spin statistics from convex models J. Torppa, V.-P. Hentunen, P. Pääkkönen, P. Kehusmaa, K. Muinonen To cite this version: J. Torppa, V.-P. Hentunen, P. Pääkkönen, P. Kehusmaa, K. Muinonen. Asteroid shape and spin statistics from convex models. Icarus, Elsevier, 2008, 198 (1), pp.91. 10.1016/j.icarus.2008.07.014. hal-00499092 HAL Id: hal-00499092 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00499092 Submitted on 9 Jul 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Asteroid shape and spin statistics from convex models J. Torppa, V.-P. Hentunen, P. Pääkkönen, P. Kehusmaa, K. Muinonen PII: S0019-1035(08)00283-2 DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2008.07.014 Reference: YICAR 8734 To appear in: Icarus Received date: 18 September 2007 Revised date: 3 July 2008 Accepted date: 7 July 2008 Please cite this article as: J. Torppa, V.-P. Hentunen, P. Pääkkönen, P. Kehusmaa, K. Muinonen, Asteroid shape and spin statistics from convex models, Icarus (2008), doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2008.07.014 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Narrative, Public Cultures and Visuality in Indian Comic Strips and Graphic Novels in English, Hindi, Bangla and Malayalam from 1947 to the Present

UGC MRP - COMICS BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Narrative, Public Cultures and Visuality in Indian Comic Strips and Graphic Novels in English, Hindi, Bangla and Malayalam from 1947 to the Present UGC MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT F.NO. 5-131/2014 (HRP) DT.15.08.2015 Principal Investigator: Aneeta Rajendran, Gargi College, University of Delhi UGC MRP INDIAN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Acknowledgements This work was made possible due to funding from the UGC in the form of a Major Research Project grant. The Principal Investigator would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Project Fellow, Ms. Shreya Sangai, in drafting this report as well as for her hard work on the Project through its tenure. Opportunities for academic discussion made available by colleagues through formal and informal means have been invaluable both within the college, and in the larger space of the University as well as in the form of conferences, symposia and seminars that have invited, heard and published parts of this work. Warmest gratitude is due to the Principal, and to colleagues in both the teaching and non-teaching staff at Gargi College, for their support throughout the tenure of the project: without their continued help, this work could not have materialized. Finally, much gratitude to Mithuraaj for his sustained support, and to all friends and family members who stepped in to help in so many ways. 1 UGC MRP INDIAN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Project Report Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. Scope and Objectives 3 2. Summary of Findings 3 2. Outcomes and Objectives Attained 4 3. -

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars -****- by Tamarapu Sampath Kumaran About the Author: Mr T Sampath Kumaran is a freelance writer. He regularly contributes articles on Management, Business, Ancient Temples and Temple Architecture to many leading Dailies and Magazines. His articles for the young is very popular in “The Young World section” of THE HINDU. He was associated in the production of two Documentary films on Nava Tirupathi Temples, and Tirukkurungudi Temple in Tamilnadu. His book on “The Path of Ramanuja”, and “The Guide to 108 Divya Desams” in book form on the CD, has been well received in the religious circle. Preface: Tirth Yatras or pilgrimages have been an integral part of Hinduism. Pilgrimages are considered quite important by the ritualistic followers of Sanathana dharma. There are a few centers of sacredness, which are held at high esteem by the ardent devotees who dream to travel and worship God in these holy places. All these holy sites have some mythological significance attached to them. When people go to a temple, they say they go for Darsan – of the image of the presiding deity. The pinnacle act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to look upon the image so as to see and be seen by the deity and to gain the blessings. There are thousands of Siva sthalams- pilgrimage sites - renowned for their divine images. And it is for the Darsan of these divine images as well the pilgrimage places themselves - which are believed to be the natural places where Gods have dwelled - the pilgrimage is made. -

Buddhist Histories

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 25 Number 1-2 2002 Buddhist Histories Richard SALOMON and Gregory SCHOPEN On an Alleged Reference to Amitabha in a KharoÒ†hi Inscription on a Gandharian Relief .................................................................... 3 Jinhua CHEN Sarira and Scepter. Empress Wu’s Political Use of Buddhist Relics 33 Justin T. MCDANIEL Transformative History. Nihon Ryoiki and Jinakalamalipakara∞am 151 Joseph WALSER Nagarjuna and the Ratnavali. New Ways to Date an Old Philosopher................................................................................ 209 Cristina A. SCHERRER-SCHAUB Enacting Words. A Diplomatic Analysis of the Imperial Decrees (bkas bcad) and their Application in the sGra sbyor bam po gnis pa Tradition....................................................................................... 263 Notes on the Contributors................................................................. 341 ON AN ALLEGED REFERENCE TO AMITABHA IN A KHARO∑™HI INSCRIPTION ON A GANDHARAN RELIEF RICHARD SALOMON AND GREGORY SCHOPEN 1. Background: Previous study and publication of the inscription This article concerns an inscription in KharoÒ†hi script and Gandhari language on the pedestal of a Gandharan relief sculpture which has been interpreted as referring to Amitabha and Avalokitesvara, and thus as hav- ing an important bearing on the issue of the origins of the Mahayana. The sculpture in question (fig. 1) has had a rather complicated history. According to Brough (1982: 65), it was first seen in Taxila in August 1961 by Professor Charles Kieffer, from whom Brough obtained the photograph on which his edition of the inscription was based. Brough reported that “[o]n his [Kieffer’s] return to Taxila a month later, the sculpture had dis- appeared, and no information about its whereabouts was forthcoming.” Later on, however, it resurfaced as part of the collection of Dr. -

EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA the Early History of Central Asia Is Gleaned

CHAPTER FOUR EASTERN CENTRAL ASIA KASHGAR TO KHOTAN I. INTRODUCTION The early history of Central Asia is gleaned primarily from three major sources: the Chinese historical writings, usually governmental records or the diaries of the Bud dhist pilgrims; documents written in Kharosthl-an Indian script also adopted by the Kushans-(and some in an Iranian dialect using technical terms in Sanskrit and Prakrit) that reveal aspects of the local life; and later Muslim, Arab, Persian, and Turkish writings. 1 From these is painstakingly emerging a tentative history that pro vides a framework, admittedly still fragmentary, for beginning to understand this vital area and prime player between China, India, and the West during the period from the 1st to 5th century A.D. Previously, we have encountered the Hsiung-nu, particularly the northern branch, who dominated eastern Central Asia during much of the Han period (206 B.C.-220 A.D.), and the Yiieh-chih, a branch of which migrated from Kansu to northwest India and formed the powerful and influential Kushan empire of ca. lst-3rd century A.D. By ca. mid-3rd century the unified Kushan empire had ceased and the main line of kings from Kani~ka had ended. Another branch (the Eastern Kushans) ruled in Gandhara and the Indus Valley, and the northernpart of the former Kushan em pire came under the rule of Sasanian governors. However, after the death of the Sasanian ruler Shapur II in 379, the so-called Kidarites, named from Kidara, the founder of this "new" or Little Kushan Dynasty (known as the Little Yiieh-chih by the Chinese), appear to have unified the area north and south of the Hindu Kush between around 380-430 (likely before 410). -

Persian Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY PERSIAN ROYAL ANCESTRY Achaemenid Dynasty from Greek mythical Perses, (705-550 BC) یشنماخه یهاشنهاش (Achaemenid Empire, (550-329 BC نايناساس (Sassanid Empire (224-c. 670 INTRODUCTION Persia, of which a large part was called Iran since 1935, has a well recorded history of our early royal ancestry. Two eras covered are here in two parts; the Achaemenid and Sassanian Empires, the first and last of the Pre-Islamic Persian dynasties. This ancestry begins with a connection of the Persian kings to the Greek mythology according to Plato. I have included these kind of connections between myth and history, the reader may decide if and where such a connection really takes place. Plato 428/427 BC – 348/347 BC), was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. King or Shah Cyrus the Great established the first dynasty of Persia about 550 BC. A special list, “Byzantine Emperors” is inserted (at page 27) after the first part showing the lineage from early Egyptian rulers to Cyrus the Great and to the last king of that dynasty, Artaxerxes II, whose daughter Rodogune became a Queen of Armenia. Their descendants tie into our lineage listed in my books about our lineage from our Byzantine, Russia and Poland. The second begins with King Ardashir I, the 59th great grandfather, reigned during 226-241 and ens with the last one, King Yazdagird III, the 43rd great grandfather, reigned during 632 – 651. He married Maria, a Byzantine Princess, which ties into our Byzantine Ancestry. -

Struggle of Titans: Book 1

From 538 BC to 231 BC, Carthage began as a dominant power along with the Etruscans and the Greeks. By 231 BC, Rome was the dominant power, and Carthage had taken major steps to conceal from the Romans, their buildup of forces in preparation to combat and overcome Rome. STRUGGLE OF TITANS: BOOK 1 by Lou Shook Order the complete book from the publisher Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/9489.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Copyright © 2017 Lou Shook ISBN: 978-1-63492-606-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., St. Petersburg, Florida. Printed on acid-free paper. This is a work of historical fiction, based on actual persons and events. The author has taken creative liberty with many details to enhance the reader's experience. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2017 First Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE - BEGINNING OF CARTHAGE (2800-539 BC) ................. 9 CHAPTER TWO - CARTHAGE CONTINUES GROWTH (538-514 BC) ....................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER THREE - CARTHAGE SECURES WESTERN MEDITERREAN (514-510 BC) ............................................................. 32 CHAPTER FOUR - ROME REPLACES MONARCHY (510-508 BC) ...................................................................................... -

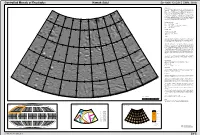

Hi-Resolution Map Sheet

Controlled Mosaic of Enceladus Hamah Sulci Se 400K 43.5/315 CMN, 2018 GENERAL NOTES 66° 360° West This map sheet is the 5th of a 15-quadrangle series covering the entire surface of Enceladus at a 66° nominal scale of 1: 400 000. This map series is the third version of the Enceladus atlas and 1 270° West supersedes the release from 2010 . The source of map data was the Cassini imaging experiment (Porco et al., 2004)2. Cassini-Huygens is a joint NASA/ESA/ASI mission to explore the Saturnian 350° system. The Cassini spacecraft is the first spacecraft studying the Saturnian system of rings and 280° moons from orbit; it entered Saturnian orbit on July 1st, 2004. The Cassini orbiter has 12 instruments. One of them is the Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem 340° (ISS), consisting of two framing cameras. The narrow angle camera is a reflecting telescope with 290° a focal length of 2000 mm and a field of view of 0.35 degrees. The wide angle camera is a refractor Samad with a focal length of 200 mm and a field of view of 3.5 degrees. Each camera is equipped with a 330° 300° large number of spectral filters which, taken together, span the electromagnetic spectrum from 0.2 60° 320° 310° to 1.1 micrometers. At the heart of each camera is a charged coupled device (CCD) detector 60° consisting of a 1024 square array of pixels, each 12 microns on a side. MAP SHEET DESIGNATION Peri-Banu Se Enceladus (Saturnian satellite) 400K Scale 1 : 400 000 43.5/315 Center point in degrees consisting of latitude/west longitude CMN Controlled Mosaic with Nomenclature Duban 2018 Year of publication IMAGE PROCESSING3 Julnar Ahmad - Radiometric correction of the images - Creation of a dense tie point network 50° - Multiple least-square bundle adjustments 50° - Ortho-image mosaicking Yunan CONTROL For the Cassini mission, spacecraft position and camera pointing data are available in the form of SPICE kernels. -

Seepage of Water from the River Indus and Occurrence of Fresh Ground Water in Sindh

SEEPAGE OF WATER FROM THE RIVER INDUS AND OCCURRENCE OF FRESH GROUND WATER IN SINDH BY M.H. PANHWAR I was involved with investigation of ground water in the Province of Sindh since 1953, with the first assignment as Agricultural Engineer in Sindh. My previous experience in various areas of Sindh had revealed that in many cases even at shallow depths of a few meters, ground water was brackish in the Indus plains of Sindh. The easiest solution for the initial ground water survey was to take samples out from the existing dug and lined wells which were about 10 meters deep and also from hand pumps of same depth used for domestic purposes. Such wells and hand pumps existed in each one of some 20,000 sizeable villages in the Indus Alluvial Plains. A representative survey of about 2,000 such water sources showed that ground water in the close vicinity of the river Indus was invariably fresh, in the first 280 miles of its run in Sindh from Kashmore to Hyderabad, but was slightly brackish on the down streams side up to the point, where it discharged into the Arabian sea. This general rule did not apply to whole Sindh as there were areas, even 40 miles away from the river Indus, which also had fresh water. I therefore thought that the river Indus which has been changing courses periodically had passed through such areas in the recent centuries and seepage from it has left fresh water there. It appeared that, if I could get correct information on the courses of the river Indus in the past, the occurrence and the quality of ground water could probably be known comparatively more reliably. -

Bijildings on the West Side of the Ag-Ora

BIJILDINGS ON THE WEST SIDE OF THE AG-ORA PLATES I-VITI INTRODUCTION' The region to the north of the Areopagus and to the east of Kolonos Agoraios had many natural advantages to recommend it as the site for thZecentral public place of the com- munity (Fig. 1). It was the most open and level area of any extent beneath the immediate shelter of the Acropolis. Along its southern edge a series of springs bubbled out from the foot of the Areopagus, so abundant as to have formed the principal source of drinking water in the city throughout antiquity. A gentle slope toward the north guaranteed adequate natural drainage, desirable for private habitation and essential for the construc- tion of large public buildings. The region lay, moreover, on the direct route between the Acropolis and the Dipylon, the principal gate of the city, and so was conveniently situated alike for residents and visitors. Actual habitation in the area can now be shown to extend at least well back into the second millennium B.C. Scattered fragments of household pottery of typical Middle Helladic types, Gray Minyan and Matt-painted wares, have appeared above bedrock along the north foot of the Areopagus, along the east slope and foot of Kolonos and even at the north foot of Kolonos. A simple shaft burial not later than this period was made near the mid point of the east foot of the latter hill 2 (Fig. 64, Section C-C). Practically no house- hold pottery of Late Helladic times has been found in the area so that there is no direct evidence for habitation in this period.