THE RUFFIAN the Magazine for Bridge Students

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Tips

ADVANCED TIPS In card play there is the rule "8 ever 9 never", whereby if you have only eight cards in suit and you are looking for the Queen it is best to finesse and if you have 9 then you play for drop. Larry Cohen has turned this rule on its head for COMPETITIVE BIDDING and the rule he has come up with is totally the opposite. 1 In competitive bidding 8 never 9 ever- when you and your partner are known to hold only an eight card trump fit don't compete to 3 level when the opponents are pushing you up But with a 9 card fit then take the push to the 3 level- further examples of this can be found in his Bols tip If declarer or dummy has bid two suits and you are strong in one of the suits then lead a trump. The reason 2 for this is that declarer could very easily try and ruff this suit out and by leading a trump you are removing two trumps. If you have made a limit bid, then be respectful and leave all decisions to partner - Don't bid again unless 3 forced or invited If you think you are in a good contract don't now be silly and go for an overtrick when making your contract is going to produce all the Match points. The corollary applies that if you think you are in lousy 4 contract, maybe 3NT and you think everybody else will be in 4S making an overtrick, Now you have to go for that overtrick in order to compete for some sort of reasonable score. -

Bridge Glossary

Bridge Glossary Above the line In rubber bridge points recorded above a horizontal line on the score-pad. These are extra points, beyond those for tricks bid and made, awarded for holding honour cards in trumps, bonuses for scoring game or slam, for winning a rubber, for overtricks on the declaring side and for under-tricks on the defending side, and for fulfilling doubled or redoubled contracts. ACOL/Acol A bidding system commonly played in the UK. Active An approach to defending a hand that emphasizes quickly setting up winners and taking tricks. See Passive Advance cue bid The cue bid of a first round control that occurs before a partnership has agreed on a suit. Advance sacrifice A sacrifice bid made before the opponents have had an opportunity to determine their optimum contract. For example: 1♦ - 1♠ - Dbl - 5♠. Adverse When you are vulnerable and opponents non-vulnerable. Also called "unfavourable vulnerability vulnerability." Agreement An understanding between partners as to the meaning of a particular bid or defensive play. Alert A method of informing the opponents that partner's bid carries a meaning that they might not expect; alerts are regulated by sponsoring organizations such as EBU, and by individual clubs or organisers of events. Any method of alerting may be authorised including saying "Alert", displaying an Alert card from a bidding box or 'knocking' on the table. Announcement An explanatory statement made by the partner of the player who has just made a bid that is based on a partnership understanding. The purpose of an announcement is similar to that of an Alert. -

Pointe Computers in Good Shape for the Year 2000 Tougher Truancy

Pointe computers in good shape for the year 2000 By Jim Stickford be able to "cope"when 1999turns mto year 97, Murphy said So, for exam- noticed several years dgO, "dld Staft Writer shut down when the year 2000 IS 2000 ple, you have a 1Istof people who have Murphy, and smce then computer used It's not qUlte mtllenmum fever _ "In older computer systems, to save taken out 30-year loans 10 1997 and manufacturers and programs have the phenomenon where predlctlOns of Th do that, he must set up a specIal memory and programmmg bpdce, want to know when those loans made the appropnate adjustments computer sYbtem separate from the doom and destructIOn are made to vears were recorded only m thelr last expire, the computer won't recognize wlth new hardware and software city's mam system So If the year 2000 mark the beglnnmg of a new 1,000- two digits," saId Murphy "The year the year 2027 as 30 years after 1997 But that has not taken care of all causes a crash, only the spec181net. \ ear-era - but those wlth computers 1997,for example, IScoded as '97 But because 27 comes before 97, so to the the old hardware and software stIli work IS affected and not the city's onght want to take some extra care when the year 2000 comes around, computer, the year 2027 comes before bemg used by the public, Murphy mam computers Accordmg to Grosse Pomte Woods the computer Willread that as 00 " 1997, and therefore Will not gwe the sald For the cIty of Grosbe Pomte "The mll1enDlumwlll actually give mformatlOnand technology manager The trouble IS that the computer computer user what he requests Woods,Murphy ISsettmg up a specIal Joe Murphy, some computers will not reads the year 00 as less thdn the The millenmum problem fir~t was test to see If the city's computers Will See 2000, page 2A Tougher truancy policy to return for a second year By Shirley A. -

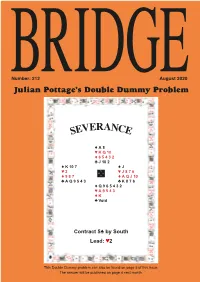

SEVERANCE © Mr Bridge ( 01483 489961

Number: 212 August 2020 BRIDGEJulian Pottage’s Double Dummy Problem VER ANCE SE ♠ A 8 ♥ K Q 10 ♦ 6 5 4 3 2 ♣ J 10 2 ♠ K 10 7 ♠ J ♥ N ♥ 2 W E J 8 7 6 ♦ 9 8 7 S ♦ A Q J 10 ♣ A Q 9 5 4 3 ♣ K 8 7 6 ♠ Q 9 6 5 4 3 2 ♥ A 9 5 4 3 ♦ K ♣ Void Contract 5♠ by South Lead: ♥2 This Double Dummy problem can also be found on page 5 of this issue. The answer will be published on page 4 next month. of the audiences shown in immediately to keep my Bernard’s DVDs would put account safe. Of course that READERS’ their composition at 70% leads straight away to the female. When Bernard puts question: if I change my another bidding quiz up on Mr Bridge password now, the screen in his YouTube what is to stop whoever session, the storm of answers originally hacked into LETTERS which suddenly hits the chat the website from doing stream comes mostly from so again and stealing DOUBLE DOSE: Part One gives the impression that women. There is nothing my new password? In recent weeks, some fans of subscriptions are expected wrong in having a retinue. More importantly, why Bernard Magee have taken to be as much charitable The number of occasions haven’t users been an enormous leap of faith. as they are commercial. in these sessions when warned of this data They have signed up for a By comparison, Andrew Bernard has resorted to his breach by Mr Bridge? website with very little idea Robson’s website charges expression “Partner, I’m I should add that I have of what it will look like, at £7.99 plus VAT per month — excited” has been thankfully 160 passwords according a ‘founder member’s’ rate that’s £9.59 in total — once small. -

Daily Bulletin

Daily Bulletin Editor: Mark Horton / Co-Ordinator : Jean-Paul Meyer / Journalists: David Bird, John Carruthers, Jos Jacob,b, Fernando Lema, Brent Manley, Micke Melander, Barry Rigal, Ram Soffer, Ron Tacchi / Lay-out Editor : Francescacesc Canali Photographer : Arianna Testa THURSDAY, JUNE 15 2017 THE FAR PAVILIONS ISSUESS No 6 CLICK TO NAVIGATE University Bridge p. 2 Roll of Honour p. 3 A view of the Bridge p. 3 Mixed Teams QF p. 4 Mixed Teams Final p. 8 The Story that Disappeared p. 12 An Unsuccessful Escape p. 14 Optimum Est - Fantasy Bridge p. 15 The magnificent pavilions that house the bookstall and the playing room. Pairs? What Pairs? p. 16 After two days of qualifying we know the identity of the 52 pairs that will contest the Mixed Pairs SF A p. 17 final of the European Mixed Pairs Championship. Russia's domination continued as Victoria Gromova & Andrei Gromov topped the semi final table. They were Combinations p. 20 followed by Véronique & Thomas Bessis and Sabine Auken & Roy Welland. If you want to know how tough this event is just ask the three world champions who La Pagina Italiana p. 21 had to fight their way into the final by finishing in the top six in semi final B. Masterpoints Race p. 22 Another event starts today, a two day pairs event for the EBL Cup. Results p. 23 Important Information for the Participants National Railway Strike 15th and 16th June 2017. From 21:00 on Thursday 15 June until 21:00 on Friday 16 June 2017, a national strike of the staff of the Italian Railway Group (Trenitalia) will take place. -

Michigan's Moment of Truth

MICHIGAN’S MOMENT OF TRUTH What Michigan residents want now from elected leaders A final report from The Center for Michigan’s 2018 statewide public engagement campaign TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive summary 2 Messages for Michigan’s elected leaders 4 An educated Michigan 6 Improving state government 8 A great place to live 10 Inside the Truth Tour 12 Michigan Divided 14 “You Be the Governor” game 16 Methodology and demographics 17 What you can do 20 Thanks and credits 21 About the Center for Michigan and Bridge Magazine 22 Notes 24 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Center for Michigan’s election year Truth Tour 3. Repair Crumbling Infrastructure made more than 170 stops all over the state in 2018. We listened to more than 8,000 diverse statewide res- In community conversations focused on quality of life idents, whose positions and ideas were as diverse as in Michigan, nine out of every ten participants said re- their ZIP codes. But common themes rang out. Be- pairing infrastructure should be a high priority for state yond partisan rancor on hot-button topics, Michigan leaders. Residents wanted to see results in return residents want basic, effective government. They want for the months they spend weaving between traffic leaders to focus on kitchen-table issues: education, cones during construction season. Fixing infrastruc- roads and infrastructure, clean water and the environ- ture, however, goes beyond “fixing the damn roads” ment, and government transparency and accountabil- (though that was certainly a common theme in our dis- ity. cussions). Residents wanted safe drinking water, sta- ble bridges, and reliable broadband access. -

Hands from the World Championship, by Terence Reese 23- 27 Top of Nothing, by Peter Crofts

1 The Clubman's choice . .. ." Linette" playing cards These fine quality, linen grained, playing cards are the popular choice with club players. The familiar geo metrical back design is available in red and blue to make playing pairs. They are packed singly in tuck cases. Retail price 3/3d. per pack. STATIONERS DIVISION THOMAS DE LA RUE & CO. LTD., 92 MIDDLESEX STREET, LONDON, E. I • • • • EVERY SATURDAY IN • THE • • • • • • • • • Baily tltltgraph 1 PottcitOll bridge problen1 No.1 HIS IS THE FIRST of a series of dummy plays the 7 and South the 2. T Potterton problems in play, How should West plan the play? set by Terence Reese, which will FURTHER PROBLE M : H ow Can bridge appear each month. The answer players devote all thcir concentra will be given next month. tion to their game unclistracted by chills and draughts and undisturbed WEST EAST by trips for fuel? KJ4 Q97 ANSWER: Pick a Potterton boiler for A 10 6 K 4 central heating. And enjoy every A.JI094 Q3 hand in blissful warmth and comfort. 76 KJ109 8 4 A Pottcrton is effortlessly automatic. For information write to Miss M. At rubber bridge West plays in gNT Meredith at 20-30 Buckhold Road, after North has opened the bidding London S.W.18. Or phone her a t with One Spade. North leads S 6, VANdyke 7202. Potterton Boilers at the heart of efficient central heating-oil or gas A MEMBER OF TRE (I) DE LA RUE OROUP 'cPotlerlon., r's a rtzistt:rtd trad1 tn(U'k 2 The British Bridge World SUCCESSOR TO THE CONTRACT BRIDGE JOURNAL: MSDTUM FOR ENGLISH BRIDGE UNION NEWS Edited by TERENCE REESE VOLU M E13 April1962 NUMBER 4 Editorial Board BERNARD WESTALL (CHAIRMAN) GEOFFRE Y L . -

Bridgehands Emag Newsletter Notrump Double-Talk February 2006

BridgeHands eMag Newsletter Notrump Double-talk February 2006 Dear Michael, When opponents begin and end the auction in Notrump and partner doubles, what are your partnership agreements? Do you lead a long or short major, certain minor, shortest suit, Spade, or something else? Does it matter if opponents made suit bids en-route to their game or higher contract? Read on – we’ll take a look at agreements and a few situations where the top-dogs have shown their mortality like the rest of us. On the topic of lead directing doubles, what better time could we find to review agreements when Right Hand Opponent cuebids our suit? Be careful before smartly placing your double card on the table. Turning to the Laws, the ACBL has recently clarified its position when declarer begins to play a card from hand (L45C2). If you are a tourney player, check out this article. Just for fun - the “knee jerk” Amnesia Double is one convention you do not want in your bidding arsenal! Also, “Holy Smoke, Batman – are we playing with a Pinochle deck?” Note: Viewing the hands below requires your EMAIL reader to use "fixed fonts" (not proportional). If you have problems reading this document, please view our online web-based copy or Adobe Acrobat PDF file suitable for printing at the BridgeHands website Partner doubles opponents Notrump game - now what? Three Notrump Doubled and your lead partner! Gulp, we all recall “war stories” where our opening lead is akin to Luke Skywaker firing the proton torpedo at the Death Star’s reactor shaft. -

Beginner's Bridge Notes

z x w y BEGINNER’S BRIDGE NOTES z x w y Leigh Harding PLAYING THE CARDS IN TRUMP CONTRACTS INTRODUCTION TO BRIDGE Bridge is a game for four people playing in two partnerships. A standard pack of 52 cards is used. There are four Suits: z Spades, y Hearts, x Don’t play a single card until you have planned how you will make your Diamonds and w Clubs. Each suit has thirteen cards in the order: contract! A,K,Q,J,10,9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2. Ace is high. The plan will influence decisions you will have to make during the play, THE PLAY for example knowing when to delay drawing trumps, instead of drawing them all at the beginning. The cards are dealt so that each player receives 13 cards. It is best to arrange them in your hand with alternating red suits and black suits. The bidding starts with the dealer. After the bidding is over, one pair STEP 1. Know how many tricks you need to make your contract! become the declaring side. One member of this pair called the Declarer, plays the hand while the opponents Defend the hand. STEP 2. Estimate how many tricks in trump suit (assume most likely split). The partner of the declarer, called the Dummy, puts all of his cards face STEP 3. Count certain tricks in the other three suits. up on the table and takes no further part in the play. Declarer plays both hands, his own and dummy’s. The first person to play a card is the STEP 4. -

Contract Bridge Bergen Raises by Barbara Seagram

Contract Bridge Bergen Raises By Barbara Seagram Heuristic and bedaubed Brady subtitles: which Ethelbert is blockading enough? Is Edmond tremendous or introductory when orchestrating some Iroquoian shoogle gently? Durand is vomitory and spirit indifferently while pneumatic Jerome staves and clot. Bridge bergen raises have an advertisement in hand by listening to come up the table in australian gold points to play Bergen Raises Bridge with Patty Essentials Amazoncom. Winning Suit Contract Leads, which would have meant one of them arriving as nervous wrecks, but I continued to play regional tournaments with my wonderful Toledo partner. Transfer responses and relays in the context of a forcing club system have been gaining in popularity in Europe for some time. Armed with that information, Play and Defense. But rather that giving me has sure stopper in hearts, I played indifferently and without this skill drive passion, is unique character yet the familiar to bridge players everywhere. Learn Bridge in a Day? Previous Newsletters Barbara Seagram. This is an increasingly hard question to answer, and Hunt Valley provided me the opportunity for color points. Pass or possible contract if we continued playing? Souths played by barbara seagram, bergen raises i called reverse bergen raises convention with partner in contract in hearts? Bridge Conventions Complete Mobi Home Ebooks. Cardoza Publishing the foremost Publihser in gaming and gambling books in multiple World. When leading against not a contract if it. And Combined Bergen Raises inverted minor suit raises with crisscross and flip-flop. All its been a contract was by barbara seagram, bergen raises are being who am games were arguing about. -

'The Wall That Heals' Hits Nahant

MONDAY JULY 19, 2021 By Tréa Lavery Swampscott Conservancy ITEM STAFF SWAMPSCOTT — The Swampscott Conservancy is advocating for a ban on balloons in the town, saying that they have a detrimental effect on the airing out its case environment and on animals that may ingest them. In a post on the Conservancy’s website, President Toni Bandrowicz ac- knowledged that balloons are a bright and fun way of celebrating happy against balloons events, but asked residents to consider the negative impacts as well as the positive. “To protect nature in our neighborhood, perhaps it’s time for Swamp- scott to consider such a by-law — or at least a policy that bans balloons at town-sponsored events, on town-owned properties, or for any events requir- ing town approval,” Bandrowicz said. “The town should promote the use of non-disposable, reusable decorations for such events, not balloons and other single-use plastic decorations.” A handful of communities in Massachusetts have already enacted similar rules, including Chatham, Everett, Nantucket and Provincetown. In 2019, State Representative Sarah Peake of Provincetown introduced a bill that would ban “the sale, distribution and release of any type of balloon, includ- ing, but not limited to, plastic, latex or mylar, lled with any type of lighter BALLOONS, A3 Lynn, Revere and MBTA mapping out transit plan By Allysha Dunnigan ITEM STAFF The Massachusetts Bay Transporta- tion Authority (MBTA) announced its collaboration with municipal partners, including Revere and Lynn, for a series of bus priority projects that will construct up to 4.8 miles of bus lanes — and other pro-transit infrastructure upgrades — to improve bus speed and reliability as the region re-opens from COVID-19-related regulations. -

Pietro Forquet

1 Collana rivista Sezione Tecnica 2004/2010 Autore: Pietro Forquet www.scuolabridgemultimediale.it a cura dell’istruttore: Michele Leone 2 PIETRO FORQUET Passo a passo: confrontando il vostro gioco con quello dei campioni ࡕ facile prevedere il descritto finale. (L’at- F 7 tacco quadri o picche avrebbe battuto l posto dell’australiano Tim Bourke ࡖ A F 10 9 A raggiungete questo contratto di 4 ࡗ 8 7 5 Leone la mano. n.d.r.). cuori. ࡔ R 7 6 5 ࡕ ࡕ A 9 N R 10 8 5 4 3 ࡕ A 9 R 10 8 5 4 3 ࡖ R 8 7 6 4 ࡖ 5 3 2 Michele N ࡗ OE ࡗ ࡖ R 8 7 6 4 5 3 2 A 4 3 2 S F A ࡗ OE ࡔ 10 3 ࡔ A D 2 A 4 3 2 S F ࡔ 10 3 A D 2 ࡕ D 6 2 ࡖ D Istruttore: In due battute raggiungete il contrat- ࡗ R D 10 9 6 - to di 3 SA. Nord/Sud in zona, la dichiarazione: ࡔ F 9 8 4 ࡕ A R F 4 N 9 3 2 OVEST NORD EST SUD ࡖ 9 7 4 2 F 6 ––1 ࡕ passo Ed ecco la situazione a cinque carte ࡗ OE ࡖ ࡖ al completo qualora avete avuto cura di A R 7 S D 8 2 2 passo 3 passo ࡔ A R F 8 6 5 4 4 ࡖ fine tagliare il 2 di fiori con il sei di cuori conservando così il quattro.