THE BLUES SCALE Phillip Pedler This Scale Is So Often Overlooked As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

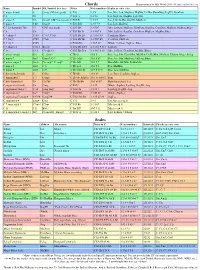

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks

Topic: Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks Key vocabulary: Core knowledge questions Powerful knowledge crucial to commit to long term Links to previous and future topics memory 12-Bar Blues, Blues 45. What are the key features of blues music? • Learn about the history, origins and Links to chromatic Notes from year 8. Chord Sequence, 46. What are the main chords used in the 12-bar blues sequence? development of the Blues and its characteristic Links to Celtic Music from year 8 due to Improvisation 47. What other styles of music led to the development of blues 12-bar Blues structure exploring how a walking using improvisation. Links to form & Syncopation Blues music? bass line is developed from a chord structure from year 9 and Hooks & Riffs Scale Riffs 48. Can you explain the term improvisation and what does it mean progression. in year 9. Fills in blues music? • Explore the effect of adding a melodic Solos 49. Can you identify where the chords change in a 12-bar blues improvisation using the Blues scale and the Make links to music from other cultures Chords I, IV, V, sequence? effect which “swung”rhythms have as used in and traditions that use riff and ostinato- Blues Song Lyrics 50. Can you explain what is meant by ‘Singin the Blues’? jazz and blues music. based structures, such as African Blues Songs 51. Why did music play an important part in the lives of the African • Explore Ragtime Music as a type of jazz style spirituals and other styles of Jazz. -

Minor Pentatonic & Blues- the Five Box Shapes

Minor Pentatonic & Blues- The Five Box Shapes Now we will add one note to the minor pentatonic scale and turn it into the six-note blues scale. Pentatonic & Blues scales are the most commonly used scales in most genres of music. We can add the flat 5, (b5), or blue note to the pentatonic scale, making it a six-note scale called the Blues Scale. That b5, or blue note, adds a lot of tension and color to the scale. These are “must-know” scales especially for blues and rock so be sure to memorize them and add them to your soloing repertoire. Most of the time when soloing with minor pentatonic scales you can also use the blues scale. To be safe, at first, use the blue note more in passing for color, don’t hang on it too long. Hanging on that flat five too long can sound a bit dissonant. It’s a great note though, so experiment with it and let your ear guide you. The five box shapes illustrated below cover the entire neck. These five positions are the architecture to build licks and runs as well as to connect into longer expanded scales. To work freely across the entire neck you will want to memorize all five positions as well as the two expanded scales illustrated on the next page. These scale shapes are moveable. The key is determined by the root notes illustrated in black. If you want to solo in G minor pentatonic play box #1 using your first finger starting at the 3rd fret on the low E-string and play the shape from there. -

Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – a Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales –

International Journal of Affective Engineering Vol.12 No.2 pp.309-315 (2013) Special Issue on KEER 2012 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Construction and Verification of the Scale Detection Method for Traditional Japanese Music – A Method Based on Pitch Sequence of Musical Scales – Akihiro KAWASE Department of Corpus Studies, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, 10-2 Midori-cho, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-8561, Japan Abstract: In this study, we propose a method for automatically detecting musical scales from Japanese musical pieces. A scale is a series of musical notes in ascending or descending order, which is an important element for describing the tonal system (Tonesystem) and capturing the characteristics of the music. The study of scale theory has a long history. Many scale theories for Japanese music have been designed up until this point. Out of these, we chose to formulate a scale detection method based on Seiichi Tokawa’s scale theories for traditional Japanese music, because Tokawa’s scale theories provide a versatile system that covers various conventional scale theories. Since Tokawa did not describe any of his scale detection procedures in detail, we started by analyzing his theories and understanding their characteristics. Based on the findings, we constructed the scale detection method and implemented it in the Java Runtime Environment. Specifically, we sampled 1,794 works from the Nihon Min-yo Taikan (Anthology of Japanese Folk Songs, 1944-1993), and performed the method. We compared the detection results with traditional research results in order to verify the detection method. If the various scales of Japanese music can be automatically detected, it will facilitate the work of specifying scales, which promotes the humanities analysis of Japanese music. -

Scale Theory -Blues Scale

Scale Theory -Blues Scale Remember we derived the C scale using 221-2221 for the number of half steps? C Db D Eb E F G Ab A Bb B C C 2 D 2 E 1 F2 G 2 A 2 B 1 C - C major scale is C D E F G A B C The major pentatonic (5 tone) scale is CDEGA or the 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 of the scale The minor pentatonic (5 tone) scale is CEbFGBb or the 1, b3, 4, 5 and b7 The blues scale can be found like that too -adds a b5 to the minor pentatonic scale We could also use a formula: 3 2 1 1 3 2 (steps) - Let's start with the key of C First, write all possible notes C Db D Eb E F Gb G Ab A Bb B C use the formula: C 3 Eb 2 F 1 Gb 1 G 3 Bb 2 C Position in major scale: 1 b3 4 b5 5 b7 1 Therefore, the C blues scale is C Eb F Gb G Bb C *This method will work for the blues scale in any key - try it for the A Blues scale Find the A blues scale: write all possible notes A A# B C C# D D# E F F# G G#A use the formula for the blues scale 321-132 A 3 C 2 D1D#1E 3 G 2 A Position in major scale: 1 b3 4 b5 5 b7 1 Therefore, the A major scale is A C D D# E G A You can play the blues scale in a linear fashion, up the neck – note that the notes are shown by the fret marker dots, with only the b5 added at the 6th fret. -

250 + Musical Scales and Scalecodings

250 + Musical Scales and Scalecodings Number Note Names Of Notes Ascending Name Of Scale In Scale from C ScaleCoding Major Suspended 4th Chord 4 C D F G 3/0/2 Major b7 Suspend 4th Chord 4 C F G Bb 3/0/3 Major Pentatonic 5 C D E G A 4/0/1 Ritusen Japan, Scottish Pentatonic 5 C D F G A 4/0/2 Egyptian \ Suspended Pentatonic 5 C D F G Bb 4/0/3 Blues Pentatonic Minor, Hard Japan 5 C Eb F G Bb 4/0/4 Major 7-b5 Chord \ Messiaen Truncated Mode 4 C Eb G Bb 4/3/4 Minor b7 Chord 4 C Eb G Bb 4/3/4 Major Chord 3 C E G 4/34/1 Eskimo Tetratonic 4 C D E G 4/4/1 Lydian Hexatonic 6 C D E G A B 5/0/1 Scottish Hexatonic 6 C D E F G A 5/0/2 Mixolydian Hexatonic 6 C D F G A Bb 5/0/3 Phrygian Hexatonic 6 C Eb F G Ab Bb 5/0/5 Ritsu 6 C Db Eb F Ab Bb 5/0/6 Minor Pentachord 5 C D Eb F G 5/2/4 Major 7 Chord 4 C E G B 5/24/1 Phrygian Tetrachord 4 C Db Eb F 5/24/6 Dorian Tetrachord 4 C D Eb F 5/25/4 Major Tetrachord 4 C D E F 5/35/2 Warao Tetratonic 4 C D Eb Bb 5/35/4 Oriental 5 C D F A Bb 5/4/3 Major Pentachord 5 C D E F G 5/5/2 Han-Kumo? 5 C D F G Ab 5/23/5 Lydian, Kalyan F to E ascending naturals 7 C D E F# G A B 6/0/1 Ionian, Major, Bilaval C to B asc. -

ANNEXURE Credo Theory of Music Training Programme GRADE 5 by S

- 1 - ANNEXURE Credo Theory of Music training programme GRADE 5 By S. J. Cloete Copyright reserved © 2017 BLUES (JAZZ). (Unisa learners only) WHAT IS THE BLUES? The Blues is a musical genre* originated by African Americans in the Deep South of the USA around the end of the 19th century. The genre developed from roots in African musical traditions, African-American work songs, spirituals and folk music. The first appearance of the Blues is often dated to after the ending of slavery in America. The slavery was a sad time in history and this melancholic sound is heard in Blues music. The Blues, ubiquitous in jazz and rock ‘n’ roll music, is characterized by the call-and- response* pattern, the blues scale (which you are about to learn) and specific chord progressions*, of which the twelve-bar blues* is the most common. Blue notes*, usually 3rds or 5ths flattened in pitch, are also an essential part of the sound. A swing* rhythm and walking bass* are commonly used in blues, country music, jazz, etc. * Musical genre: It is a conventional category that identifies some music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions, e.g. the blues, or classical music or opera, etc. They share a certain “basic musical language”. * Call-and-response pattern: It is a succession of two distinct phrases, usually played by different musicians (groups), where the second phrase is heard as a direct commentary on or response to the first. It can be traced back to African music. * Chord progressions: The blues follows a certain chord progression and the th th 7 b harmonic 7 (blues 7 ) is used much of the time (e.g. -

Musical Modes, Their Associated Chords and Their Musicality 3

MUSICAL MODES, THEIR ASSOCIATED CHORDS AND THEIR MUSICALITY MIHAIL COCOS & KENT KIDMAN Abstract. In this paper we present a mathematical way of defining musical modes and we define the musicality of a mode as a product of three differ- ent factors. We conclude by classifying the modes which are most musical according to our definition. 1. Musical scales and modes First we must define some concepts. In traditional western style of music there are 12 different notes in an octave. Two notes represent the same tone if they are at a distance of 12n semitones (a multiple of octaves apart). The 13th note restarts the cycle and it is the same tone as our first note (simply an octave higher). Loosely speaking a scale is simply an ordered sequence of different tones within the same octave. For instance CDEFGAB is the well known C major scale, ABCDEFG is the A minor scale, and EGAA#BD is the hexatonic blues scale in the key of E. The first note of the scale is said to be the key of the scale. Definition 1.1. For further considerations about scales we will associate every tone with a numerical value, namely its position in the chromatic A scale AA#BCC#CDD#EF F #GG# The lexicographic order of tones will be defined as the order induced by their nu- merical values defined as above. The precise mathematical definition of a scale is: arXiv:1201.2654v1 [math.CO] 12 Jan 2012 Definition 1.2. A k scale is a circular permutation of k different tones in lexico- graphic order. -

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale J. N. Hooker Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA [email protected] May 2017 Abstract We analyze results of a search for alternative musical scales that share the main advantages of classical scales: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an un- derlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. The search is based on combinatorics and a constraint programming model that assigns frequency ratios to intervals. We find that certain 11-note scales on a 19-note chromatic stand out as superior to all others. These scales enjoy harmonic and structural possibilities that go significantly beyond what is available in classical scales and therefore provide a possible medium for innovative musical composition. 1 Introduction The classical major and minor scales of Western music have two attractive characteristics: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an underlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. Simple ratios allow for rich and intelligible harmonies, while multiple keys greatly expand possibilities for complex musical structure. While these tra- ditional scales have provided the basis for a fabulous outpouring of musical creativity over several centuries, one might ask whether they provide the natural or inevitable framework for music. Perhaps there are alternative scales with the same favorable characteristics|simple ratios and multiple keys|that could unleash even greater creativity. This paper summarizes the results of a recent study [8] that undertook a systematic search for musically appealing alternative scales. The search 1 restricts itself to diatonic scales, whose adjacent notes are separated by a whole tone or semitone. -

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: a Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1

The Consecutive-Semitone Constraint on Scalar Structure: A Link Between Impressionism and Jazz1 Dmitri Tymoczko The diatonic scale, considered as a subset of the twelve chromatic pitch classes, possesses some remarkable mathematical properties. It is, for example, a "deep scale," containing each of the six diatonic intervals a unique number of times; it represents a "maximally even" division of the octave into seven nearly-equal parts; it is capable of participating in a "maximally smooth" cycle of transpositions that differ only by the shift of a single pitch by a single semitone; and it has "Myhill's property," in the sense that every distinct two-note diatonic interval (e.g., a third) comes in exactly two distinct chromatic varieties (e.g., major and minor). Many theorists have used these properties to describe and even explain the role of the diatonic scale in traditional tonal music.2 Tonal music, however, is not exclusively diatonic, and the two nondiatonic minor scales possess none of the properties mentioned above. Thus, to the extent that we emphasize the mathematical uniqueness of the diatonic scale, we must downplay the musical significance of the other scales, for example by treating the melodic and harmonic minor scales merely as modifications of the natural minor. The difficulty is compounded when we consider the music of the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, in which composers expanded their musical vocabularies to include new scales (for instance, the whole-tone and the octatonic) which again shared few of the diatonic scale's interesting characteristics. This suggests that many of the features *I would like to thank David Lewin, John Thow, and Robert Wason for their assistance in preparing this article. -

Table of Contents About the Author

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR ......................................................4 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................5 CHAPTER 1— Getting Started 6 CHAPTER 6—Diatonic Harmony: 7 chords 60 The Fretboard ...............................................................................6 The 7 Chords of the Major Scale ...........................................60 Reading Standard Music Notation ............................................7 7 Chord Bass Lines ....................................................................65 Reading Bass Tablature ................................................................9 Chord Symbols .............................................................................9 CHAPTER 7—Locking-in with the Drums 66 Accidentals ..................................................................................10 Rock Grooves .............................................................................67 The Chromatic Scale .................................................................11 Funk Grooves .............................................................................68 Tuning the Bass ...........................................................................12 Reggae Grooves .........................................................................69 Right-Hand Technique ...............................................................13 Left-Hand Technique ..................................................................13 CHAPTER 8—The Blues 71 The -

" African Blues": the Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse

“African Blues”: The Sound and History of a Transatlantic Discourse A thesis submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Saul Meyerson-Knox BA, Guilford College, 2007 Committee Chair: Stefan Fiol, PhD Abstract This thesis explores the musical style known as “African Blues” in terms of its historical and social implications. Contemporary West African music sold as “African Blues” has become commercially successful in the West in part because of popular notions of the connection between American blues and African music. Significant scholarship has attempted to cite the “home of the blues” in Africa and prove the retention of African music traits in the blues; however much of this is based on problematic assumptions and preconceived notions of “the blues.” Since the earliest studies, “the blues” has been grounded in discourse of racial difference, authenticity, and origin-seeking, which have characterized the blues narrative and the conceptualization of the music. This study shows how the bi-directional movement of music has been used by scholars, record companies, and performing artist for different reasons without full consideration of its historical implications. i Copyright © 2013 by Saul Meyerson-Knox All rights reserved. ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my utmost gratitude to my advisor, Dr. Stefan Fiol for his support, inspiration, and enthusiasm. Dr. Fiol introduced me to the field of ethnomusicology, and his courses and performance labs have changed the way I think about music.