(With) Amy Ashwood Garvey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010

Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 “Whatever the cost of our libraries, the price is cheap compared to that of an ignorant nation.” Walter Cronkite Anguilla Library Service Edison L Hughes Library & Educational Complex 1 - 264- 4 9 7 - 2 4 4 1 [email protected] 3 / 3 1 / 2 0 1 1 Jan – Dec Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 2010 Department of Library Services Annual Report 2010 2 Jan – Dec Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 2010 CONTENTS 1. Director’s Remarks………………………………………………………………………………………………7 2. Information Resources…………………………………………………………………………………………8 2.1 Collection Management 2.2 Circulation and IT 2.3 Patrons 3. Staff Matters……………………………………………………………………………………………………..18 3.1 Management 3.2 Staff Development 3.3 In-House Matters 4. Reaching Out……………………………………………………………………………………………………21 4.1 Schools’ Library Programme 4.2 Cushion Club 4.3 Book of the Week 4.4 Children’s Library Annual Summer Programme 4.5 Exhibitions 5. Physical Environment……………………………………………………………………………………….43 6. Promoting Partnerships…………………………………………………………………………………….48 7. Financial Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………54 8. Going Forward…………………………………………………………………………………………………..55 Appendix 1 Sources of Support………………………………………………………………………………57 Appendix 2 ALS Organisation Chart…………………………………………………………………………60 3 Jan – Dec Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 2010 2010 At a Glance 464 customers 27,908 items checked out, 5,499 more joined the library, than last year total of library cardholders now 2903 Strategic planning for next 5 years started Community enjoyed remembering Anguillian lore More than through talks, 1,700 Internet exhibitions… bookings including WiFi users Total of 21,820 items in library database “Jolly” summer programme for kids. Over 50 children know more about “jollification” 4 Jan – Dec Anguilla Library Service Annual Report 2010 2010 MISSION STATEMENT TO PROVIDE CONTEMPORARY, COMPREHENSIVE AND INTEGRATED LIBRARY, ARCHIVES AND INFORMATION SERVICES RELEVANT TO THE SOCIAL, CULTURAL, EDUCATIONAL, BUSINESS AND INFORMATIONAL NEEDS OF THE COMMUNITY. -

Development Aid and Higher Education in Africa: the Need for More Effective Partnerships Between African Universities and Major American Foundations

CODESRIA Bulletin, Nos 1 & 2, 2012 Page 1 Editorial ODESRIA entered the year 2012 with a new Diaspora. Rabat also confirmed a trend that began earlier Executive Committee, a new President and a on; the General Assembly is becoming a great scientific Cnew Vice President, all of whom were elected attraction for scholars around the world. The debates on during the 13th General Assembly of the Council held in climate change, global knowledge divides, higher December 2011 in Rabat, Morocco. The new President education leadership, the "Arab Spring" / "African is Professor Fatima Harrak of the Institute of African Awakening", China-Africa relations, land grabbing, the Studies, Mohammad V Souissi University in Rabat, and future of multilateralism, the meaning of pan Africanism the Vice-President is Prof. Dzodzi Tshikata of the today, international migrations, and other major issues University of Ghana, Legon. The full list of members of were extremely rich, as can be seen in the summary of the new Executive Committee follows this editorial. the report of the General Assembly published in this issue As the 13th President of CODESRIA, Prof. Harrak took of the Bulletin. The full report will also soon be published. over from Prof. Sam Moyo of the Africa Institute of Most of the 200 or so papers presented at the Assembly Agrarian Studies in Harare. CODESRIA, with the are already on the CODESRIA website, and revised guidance of the Executive Committee, achieved quite a versions will be published in special issues of CODESRIA lot, including the launching of new research and policy journals and in the Book Series, as a way of extending dialogue initiatives, the publication of many good books the debates that started in Rabat to the wider scholarly and the launching of a new journal of social science community. -

Advocate, Fall 2016, Vol. 28, No. 1

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works The Advocate Archives and Special Collections Fall 2016 Advocate, Fall 2016, Vol. 28, No. 1 How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_advocate/22 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] VolumeVolume 28 27 Fall Spring no. 1n. 2016 2 2016 www.GCadvocate.comwww.GCadvocate.com [email protected]@cunydsc.org Donald Trump and the Death Rattle of Liberal Civility pg. 31 Stranger in my Skin: Racial (un)belonging in the US pg. 18 Gil Bruvel, Dichotomy, Stainless Steel sculpture editorial The Difficulty of www.GCadvocate.com Making a Voting Decision [email protected] Contents Who to vote for in the upcoming election? That is be able to keep calm as most of us have been doing? the question. In past elections, the most important Or will I punch back if I am hit—sweetly punch back things that influenced how I vetted presidential can- in the tradition of the ancestors who recognized the EDITORIAL FEATURES didates included their positions on wars, national need to deploy counter strategies that have given me security, economy, the LGBTQ community, and their the liberties I cherish today. Indeed, how powerfully The Difficulty of Stranger in my Skin: plans for developing regions like the Caribbean, where will I punch back with fists, body, talk, and silence until Making a Voting Racial (un)belonging I am from. -

West Indian Intellectuals in Britain

INTRODUCTION Crossing the seas Bill Schwarz There exists a moving photographic record of West Indian emigrants arriving in British cities in the 1950s, first by steamship and steam train, then later, by the end of the decade and into the 1960s, by plane. We still see, in our own times, these images of men and women who, for all their apprehensions, were stepping across the threshold into new lives, bringing with them a certain presence. These are images which evoke a sense of hardships in the past overcome and hardships just around the corner yet to confront. They give form to the dreams which had compelled a generation of migrants to pack up and cross the seas. And they capture too a sensibility founded on the conviction that these dreams were rightfully theirs: a dream, in other words, of colonials who believed that the privileges of empire were their due.1 These photographic images, and those of the flickering, mono- chrome newsreels which accompany them, have now come to compose a social archive. They serve to fix the collective memory of the momen- tous transformation of postwar migration. At the same time, however, their very familiarity works to conceal other angles of vision. We become so habituated to the logic of the camera-eye that we are led to forget that the vision we are bequeathed is uncompromisingly one-way. The images which fix this history as social memory are images of the West Indians. The camera is drawn to them. The moment they enter the field of vision, the focal point adjusted, they become fixed as something new: as immigrants. -

Una Marson: Feminism, Anti-Colonialism and a Forgotten fight for Freedom Alison Donnell

CHAPTER FIVE Una Marson: feminism, anti-colonialism and a forgotten fight for freedom Alison Donnell When we think about the factors that have contributed to the begin- nings of a West Indian British intellectual tradition, we would com- monly bring to mind the towering figure of C. L. R. James and his comrades of the pre-Windrush generation, such as George Padmore. It would also be important to acknowledge the generation of nationalist writers and thinkers based in the Caribbean itself, such as Roger Mais and Victor Stafford Reid. We might also think of the BBC’s Caribbean Voices which provided a much needed outlet, as well as a valuable source of income, for new writers and writings, and also, of course, of the talented community of male writers and intellectuals, such as George Lamming, Sam Selvon and V. S. Naipaul, who had come to London in the 1950s. Yet what is so commonly neglected in accounts of West Indian and black British literary and intellectual histories of the first half of the twentieth century is mention of Una Marson, a black Jamaican woman whose experiences and achievements provided a link to all these major movements and figures. It is perhaps not surprising that Marson’s identity as an intellectual is not straightforward. As an educated, middle-class daughter of a Baptist minister, Marson’s intellectual development took place within the context of a religious home where the activities of playing music and reading poetry were prized, and the conservative and colonial Hampton High School where she received an ‘English public-school education’.1 However, as one of a small number of black scholarship girls, Marson was apprenticed in the operations of racism by the time she left school. -

Pan-African History: Political Figures from Africa and The

Pan-African History Pan-Africanism, the perception by people of African origins and descent that they have interests in common, has been an important by-product of colonialism and the enslavement of African peoples by Europeans. Though it has taken a variety of forms over the two centuries of its fight for equality and against economic exploitation, commonality has been a unifying theme for many Black people, resulting for example in the Back-to-Africa movement in the United States but also in nationalist beliefs such as an African ‘supra-nation’. Pan-African History brings together Pan-Africanist thinkers and activists from the Anglophone and Francophone worlds of the past two hundred years. Included are well-known figures such as Malcolm X, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, and Martin Delany, and the authors’ original research on lesser-known figures such as Constance Cummings-John and Dusé Mohamed Ali reveals exciting new aspects of Pan-Africanism. Hakim Adi is Senior Lecturer in African and Black British History at Middlesex University, London. He is a founder member and currently Chair of the Black and Asian Studies Association and is the author of West Africans in Britain 1900–1960: Nationalism, Pan-Africanism and Communism (1998) and (with M. Sherwood) The 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress Revisited (1995). Marika Sherwood is a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London. She is a founder member and Secretary of the Black and Asian Studies Association; her most recent books are Claudia Jones: A Life in Exile (2000) and Kwame Nkrumah: The Years Abroad 1935–1947 (1996). -

Pan-Africanism and Feminism in the Early 20Th Century British Colonial Caribbean Rhoda Reddock

58 | Feminist Africa 19 The first Mrs Garvey: Pan-Africanism and feminism in the early 20th century British colonial Caribbean Rhoda Reddock It is puzzling to most feminist historians of the British colonial Caribbean that histories of pan-Africanism could be written without examining the extensive contribution of women.1 This concern is echoed by pan-Africanist scholar Horace Campbell when he notes that its ideological history has tended to focus on the contribution of great heroes, mostly males, an approach which denies the link to a broader social movement and the role of women (Campbell, 1994:286). This article examines the complementary and contradictory relationship between pan-Africanism and early feminism in the British Caribbean colonies. In highlighting the work and life of one pan-Africanist, feminist Caribbean woman, this article does not seek to propose a counter-history of great women. It seeks rather to distinguish the specific contributions made by one woman feminist – among a host of many others – to these social movements in local and international contexts and to explore the reasons why these movements provided such possibilities and the contradictions involved. The focus on Amy Ashwood Garvey highlights not just her individual significance but also allows us to acknowledge the work of countless other women (and men), some mentioned in this text, who have been excluded from the meta- narratives of these early movements. So pervasive is this narrative that Michelle Stephens in a recent review noted: The discovery of a persistent, structural, never ending, never deviating, masculinist gender politics in the discourse of black internationalism reveals a pattern that one can only explain through a deeper structural analysis of the very gendering of constructions of global blackness. -

London's Sonic Space

Introduction: London’s sonic space London provides a vast space – bigger in some senses than the nation – in which cultures can be differently imagined and conceived. (Kevin Robins) This book is about three black music multicultures in London in the 1980s and 1990s: rare groove, acid house and jungle. It is a critical explora tion of the role they have played in the production of what Stuart Hall once identified as London’s ‘workable, lived multiculture’ (Hall 2004). These are not the only important black music scenes in London: that list would include soca, jazz and Afrojazz, Afrobeat, dancehall, hip hop, UK garage, R&B and grime, and to include them all would have called for a much bigger book. So, this is not a comprehensive study of all black music produced and consumed in the city. I focus on rare groove, acid house and jungle because they are three moments that involved inter-racial collaboration, in terms of both production and consumption, around black music. They were music scenes which put the racial divisions of the city into question and worked against the logic of spatial separation. They explored new ways in which culture could be inhabited collectively. In ways both deliberate and contingent, these musical scenes involved collaboration between young people from different sides of what the great black American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois (1903) identified as ‘the color line’, and hosted lived multi culture on the dancefloor. Around each scene, discourses developed to address this cultural intermixture, and within them were forged new ways of dancing, listening and making 1 It’s a London thing culture together. -

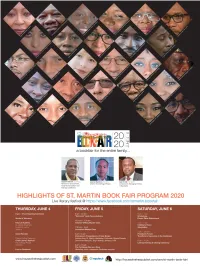

St. Martin Book Fair Program June 4 – 6, 2020

Poster pics of guest authors on the PROGRAM cover | St. Martin Book Fair 2020 L-R, Row 1: Verene Shepherd (Jamaica), Dannabang Kuwabong (Ghanaian/Canadian), Nicole Erna Mae Francis Cotton (St. Martin), Yvonne Weekes (Montserrat/Barbados), Nicole Cage (Martinique), Vladimir Lucien (St. Lucia); Row 2: Ashanti Dinah Orozco Herrera (Colombia), Karen Lord (Barbados), Jean Antoine-Dunne (Trinidad and Tobago/Ireland), Fola Gadet (Guadeloupe), A-dZiko Simba Gegele (Jamaica); Row 3: Richard Georges (Virgin Islands), Sean Taegar (Belize), Jeannine Hall Gailey (USA), Rafael Nino Féliz (Dominican Republic), Stéphanie Melyon-Reinette (Guadeloupe), Fabian Adekunle Badejo (St. Martin); Row 4: Sonia Williams (Barbados), Adrian Fraser (St. Vincent and the Grenadines), Steen Andersen (Denmark), Max Rippon (Marie-Galante, Sirissa Rawlins Sabourin (St. Kitts and Nevis); Row 5: Patricia Turnbull (Virgin Islands), Doris Dumabin (Guadeloupe), René E. Baly (St. Martin/USA), Lili Forbes (St. Martin/USA), Antonio Carmona Báez (Puerto Rico/St. Martin). *** Guest speakers/presenters, L-R: Cozier Frederick (Dominica), Minister for Environment, Rural Modernisation and Kalinago Upliftment; Lorenzo Sanford (Dominica), Chief of the Kalinago People (Dominica); Jean Arnell (St. Martin), Managing Partner and IT Specialist Computech. Click link to see all program activities: www.facebook.com/stmartin.bookfair Purpose and Objectives of the St. Martin Book Fair VISION To be the dynamic platform for books and information on and about St. Martin; establishing an eventful meeting place for the national literature of St. Martin and the literary cultures of the Caribbean; networking with literary cultures from around the world. MISSION STATEMENT To develop a marketplace for the multifaceted and multimedia exhibition and promotion of books, periodicals and publishing technologies and to facilitate St. -

Wisemind Nov2016

“The free exchange of support and ideas is an CONTENTS essential condition to world understanding and equally to world progress." - Haile Selassie 1 Wisemind e-magazine would like to thank PG 3 ….………… OUR EMPEROR SPEAKS all the people who have helped and are helping PG 4 …….... THE GRAND CORONATION to make this magazine a reality. PG 8 ……….………... HOMESCHOOLING: AN IMPORTANT EDUCATION OPTION We would like to take this opportunity to invite ones to submit news, views & opinions, however this invitation PG 11 …………………. ANCIENT SOUNDS does not guarantee immediate publication, but may be PG 14 …………….. AFRICANS LIVE ON A published, also depending upon available space. CONTINENT OWNED BY EUROPEANS! ARTICLES, REASONINGS AND PG 21 …………...... HENRY LOUIS GATES PHOTOGRAPHS CAN BE SENT TO: PG 22 ………… TEACHER ALTHEA - POEM [email protected] PG 24……................. ADVERTISEMENTS THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE CAN BE DOWNLOADED FREE @ TRICESBABY.COM/?P=3041 WISEMINDPUBLICATIONS.COM/NEWS COVER DESIGN: RAS RAVIN-I COVER ART: CHARLES KITTRELL LAYOUT: RAVIN-I / KATRICE BEEPATH GRAPHIC DESIGN: RAVIN-I / KATRICE BEEPATH CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: IJAHNYA CHRISTIAN / SIS. JENNIFER BALALA TRANSCRIPTIONS: RAS FLAKO / RAS RAVIN-I CHIEF EDITOR – KATRICE BEEPATH DISCLAIMER: THE ARTICLES CONTAINED IN THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE ARE NOT NECESSARILY THE OPINIONS AND/OR IDE- OLOGY OF THE WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE STAFF OR EDITORIAL MANAGERS OR ANY OF OUR PERSONNEL. THE ARTICLES ARE SOLELY THE IDEAS/OPINIONS/PROPERTY OF THE CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS. ALL ARTICLES AND PHOTOGRAPHS SUBMITTED A RE SUBJECTED TO EDITING AND APPROVAL. WISEMIND E-MAGAZINE RESERVES THE RIGHT TO REFUSE SUBMISSION OF ARTICLES. NO ARTICLES, PHOTOGRAPHS OR GRAPHICS MAY BE COPIED, REPRODUCED OR STORED IN ANY TYPE OF RETRIVAL SYSTEM WITHOUT THE EXPRESS PERMISSION OF THE EDITORS OR AUTHORS. -

Amy Jacques Garvey's Feminist Prowess Liberates Women in Restructuring the UNIA

Of Life and History Volume 2 Of Life and History Article 7 7-21-2019 From "Companionate Wife" to Feminist Pioneer: Amy Jacques Garvey's Feminist Prowess Liberates Women in Restructuring the UNIA Kiana Cardenas College of the Holy Cross Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/oflifeandhistory Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Cardenas, Kiana (2019) "From "Companionate Wife" to Feminist Pioneer: Amy Jacques Garvey's Feminist Prowess Liberates Women in Restructuring the UNIA," Of Life and History: Vol. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/oflifeandhistory/vol2/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Of Life and History by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. From “Companionate Wife” to Feminist Pioneer Amy Jacques Garvey’s Feminist Prowess Liberates Women in Restructuring the UNIA Kiana Cárdenas ‘19 The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), established by Marcus Garvey and Amy Ashwood Garvey in 1914, sought to remedy the desperate institutional situation of African descendants from all over the world. Although the political organization guaranteed support for all African descendants, men and women, rooted at the heart of the organization was a masculine ideology that generated constricting gender roles, to the disadvantage of a large number of women. The structure of the UNIA solidified black men as the essential instruments for the uplifting of the race while establishing the role of women as supporters of the race, particularly through motherhood.1 Amy Jacques Garvey, the second wife of Marcus Garvey and the second-most important person of the UNIA, would become a leading feminist figure within the male-dominated organization, promoting women to the forefront of the black nationalist struggle. -

EJH Alliance, LLC Building Foundations for Self Reliance

EJH Alliance, LLC Building foundations for self reliance CARIBBEAN PHILANTHROPY: PAST AND POTENTIAL for The Ford Foundation Final Draft Etha J. Henry, President EJH Alliance, LLC [email protected] Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY …………………………………………………………… 3 II. PARAMETERS AND PURPOSE ……….…………………………………………… 7 III. STUDY GOALS AND DESIGN……………………………………………………… 8 IV. CARIBBEAN CONTEXT …………………………………………………………… 9 V. FINDINGS AND OBSERVATIONS ………………………………………………… 12 VI. STRATEGIC RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………………………. 21 VII. COMMENTARY/CONCLUSION……………………………………………………. 24 VIII. APPENDICES ………………………………………………………………………… 26 • INTERVIEW GUIDE • INDIVIDUALS INTERVIEWED • BIBLIOGRAPHY I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction “The Kalinago* determined resistance to political and cultural dominance has relevance to the people of the Caribbean today in their struggle for self determination and survival as a viable group of nations.” So states noted Scholar Beverly Steele, in her “Grenada, A History of Its People.” Participants in this study seem to validate this view. The theme of remembering and honoring history, culture and tradition as the underpinnings of Caribbean giving has reverberated throughout this Caribbean History, culture Philanthropic Tour. and traditions as underpinnings of This report represents a limited study of Caribbean Caribbean giving philanthropic giving within a subset of the English reverberated speaking Caribbean Nation States - A representative throughout the sample of The Leeward and Windward Islands: Anguilla, study tour Antigua