The Lost Throne of Queen Hetepheres from Giza: an Archaeological Experiment in Visualization and Fabrication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part 45: Birds Statues (Falcon and Vulture)

International Journal of Emerging Engineering Research and Technology Volume 5, Issue 3, March 2017, PP 39-48 ISSN 2349-4395 (Print) & ISSN 2349-4409 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.22259/ijeert.0503004 Mechanical Engineering in Ancient Egypt, Part 45: Birds Statues (Falcon and Vulture) Galal Ali Hassaan (Emeritus Professor), Department of Mechanical Design & Production, Faculty of Engineering, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt ABSTRACT The evolution of mechanical engineering in ancient Egypt is investigated in this research paper through studying the production of statues and figurines of falcons and vultures. Examples from historical eras between Predynastic and Late Periods are presented, analysed and aspects of quality and innovation are outlined in each one. Material, dynasty, main dimension (if known) and present location are also outlined to complete the information about each statue or figurine. Keywords: Mechanical engineering, ancient Egypt, falcon statues, vulture statues INTRODUCTION This is the 45th paper in a scientific research aiming at presenting a deep insight into the history of mechanical engineering during the ancient Egyptian civilization. The paper handles the production of falcon and vulture statues and figurines during the Predynastic and Dynastic Periods of the ancient Egypt history. This work depicts the insight of ancient Egyptians to birds lived among them and how they authorized its existence through statuettes and figurines. Smith (1960) in his book about ancient Egypt as represented in the Museum of Fine Arts at Boston presented a number of bird figurines including ducks from the Middle Kingdom, gold ibis from the New Kingdom and a wooden spoon in the shape of a duck and lady from the New Kingdom [1]. -

Death in the City of Light

DEATH IN THE CITY OF LIGHT The Conception of the Netherworld during the Amarna Period Master Thesis Classics and Ancient Civilizations Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University Name: Aikaterini Sofianou Email: [email protected] Student Number: s2573903 Supervisor: Prof. Olaf Kaper Second Reader: Dr. Miriam Müller Date: 14/08/2020 Table of contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 1: Historical Context..................................................................................... 6 1.1 Chronology of the Amarna Period. ...................................................................... 6 1.2 Amenhotep IV: The Innovative Early Years of His Reign. ................................. 7 1.3 Akhenaten: The Radical Changes After the Fifth Year of His Reign and the End of the Amarna Period. .............................................................................................. 10 Chapter 2: Religion and Funerary Ideology ........................................................... 14 2.1 Traditional Religion and the Afterlife................................................................ 14 2.2 Atenism: Its Roots and Development. ............................................................... 17 Chapter 3: Tombs and Non-elite Burials of the Amarna Period .......................... 22 3.1 Tombs: Their Significance and Characteristics. ................................................ 22 3.2 The Royal Tomb of Amarna ............................................................................. -

Who's Who in Ancient Egypt

Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Available from Routledge worldwide: Who’s Who in Ancient Egypt Michael Rice Who’s Who in the Ancient Near East Gwendolyn Leick Who’s Who in Classical Mythology Michael Grant and John Hazel Who’s Who in World Politics Alan Palmer Who’s Who in Dickens Donald Hawes Who’s Who in Jewish History Joan Comay, new edition revised by Lavinia Cohn-Sherbok Who’s Who in Military History John Keegan and Andrew Wheatcroft Who’s Who in Nazi Germany Robert S.Wistrich Who’s Who in the New Testament Ronald Brownrigg Who’s Who in Non-Classical Mythology Egerton Sykes, new edition revised by Alan Kendall Who’s Who in the Old Testament Joan Comay Who’s Who in Russia since 1900 Martin McCauley Who’s Who in Shakespeare Peter Quennell and Hamish Johnson Who’s Who in World War Two Edited by John Keegan Who’s Who IN ANCIENT EGYPT Michael Rice 0 London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. © 1999 Michael Rice The right of Michael Rice to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Gilding Through the Ages

Gilding Through the Ages AN OUTLINE HISTORY OF THE PROCESS IN THE OLD WORLD Andrew Oddy Research Laboratory, The British Museum, London, U.K. In 1845, Sir Edward Thomason wrote in his not public concern but technological advance which memoirs (1) a description of a visit he had made in brought an end to the use of amalgam for gilding. to certain artisans in Paris and he commented: 1814 Gilding with Gold Foil `I was surprised, however, at their secret of superior Although fire-gilding had been in widespread use in gilding of the time-pieces. I was admitted into one gilding establishment, and I found the medium was Europe and Asia for at least 1 500 years when it was similar to ours, mercury; nevertheless the French did displaced by electroplating, the origins of gilding — gild the large ornaments and figures of the chimney- that is, the application of a layer of gold to the surface piece clocks with one-half the gold we could at of a less rare metal — go back at least 5 000 years, to Birmingham, and produced a more even and finer the beginning of the third millennium B.C. The colour'. British Museum has some silver nails from the site of Much to his disgust, Thomason could not persuade Tell Brak in Northern Syria (5) which have had their the French workmen to tell him the secret of their heads gilded by wrapping gold foil over the silver. superior technique, but it seems most likely that it This is, in fact, the earliest form of gilding and it lay either in the preparation of the metal surface depends not on a physical or chemical bond between for gilding or perhaps in the final cleaning and the gold foil and the substrate, but merely on the burnishing of the gilded surface. -

The Mysterious Pyramid on Elephantine Island: Possible Origin of the Pyramid Code

Archaeological Discovery, 2017, 5, 187-223 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ad ISSN Online: 2331-1967 ISSN Print: 2331-1959 The Mysterious Pyramid on Elephantine Island: Possible Origin of the Pyramid Code Manu Seyfzadeh Lake Forest, CA, USA How to cite this paper: Seyfzadeh, M. Abstract (2017). The Mysterious Pyramid on Ele- phantine Island: Possible Origin of the After the step pyramids of the Third Dynasty and before the true pyramids of Pyramid Code. Archaeological Discovery, the Fourth Dynasty, seven mysterious minor step pyramids were built by King 5, 187-223. Sneferu1 and a predecessor. None of them were tombs. Clues as to why they https://doi.org/10.4236/ad.2017.54012 were built emerged from analyzing their orientation to objects in the sky Received: August 26, 2017 worshiped by the ancient Egyptians and hinted at a renewed preoccupation Accepted: September 19, 2017 with measuring time and the flow of the Nile. The first of the seven was built Published: September 22, 2017 on the Island of Elephantine, Egypt. Its orientation suggests that an aspect of Copyright © 2017 by author and the star Sirius was being enshrined. This paper proposes that this aspect per- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. tained to the different timings of its annual invisibility period observable from This work is licensed under the Creative either the capital at Memphis in Lower Egypt or from Upper Egypt at Ele- Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). phantine. I argue that these periods, measured in days, were converted to di- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ mensions in cubits, and consequently these numbers and the resulting geo- Open Access metric relationships between them became important. -

Joseph Lindon Smith, Whose Realistic Paintings of Interior Tomb Walls Are Featured in the Gallery;

About Fitchburg Art Museum Founded in 1929, the Fitchburg Art Museum is a privately-supported art museum located in north central Massachusetts. Art and artifacts on view: Ancient Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Asian, and Meso-American; European and American paintings (portraits, still lifes, and landscapes) and sculpture from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; African sculptures from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; Twentieth-century photography (usually); European and American decorative arts; Temporary exhibitions of historical or contemporary art Museum Hours Wednesdays-Fridays, 12 – 4 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays 11 a.m. – 5 p.m. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays, except for the following Monday holidays: Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, President’s Day, Patriot’s Day, and Columbus Day Admission Free to all Museum members and children ages 12 and under. $7.00 Adult non-members, $5.00 Seniors, youth ages 13-17, and full-time students ages 18-21 The Museum is wheelchair accessible. Directions Directions to the Museum are on our website. Address and Phone Number 25 Merriam Parkway, Fitchburg, MA 01420 978-345-4207 Visit our website for more information: www.fitchburgartmuseum.org To Schedule a Tour All groups, whether requesting a guided tour or planning to visit as self-guided, need to contact the Director of Docents to schedule their visit. Guided tours need to be scheduled at least three weeks in advance. Please contact the Director of Docents for information on fees, available tour times, and additional art projects available or youth groups. Museum Contacts Main Number: 978-345-4207 Director of Docents: Ann Descoteaux, ext. -

The Canopic Box of N%-Aa-Rw (BM EA 8539) *

THE CANOPIC BOX OF N%-aA-RW_ (BM EA 8539) * By AHMED M. MEKAWY OUDA Primary publication of the canopic box of Ns-aA-rwd, perhaps from Thebes dating to late Twenty- fifth/early Twenty-sixthD ynasties. No exact parallels exist for the texts on this box, which bears some unique epithets and unusual extensive formulations for the four protective goddesses, invoking a close relationship with Osiris and Horus, especially for Isis and Neith. The box’s owner, title, family, and status, as well as textual parallels for deities’ titles and epithets, are discussed. In the collections of the British Museum, there is a painted wooden canopic chest belonging to Ns-aA-rwd, in the form of a Pr-wr shrine with inclined roof (BM EA 8539; fig. 1).1 The museum acquired it as part of Henry Salt’s first collection, which arrived in London in 1821 and was accessioned in 1823. Each side displays a scene in which one of the four protective goddesses, Isis, Nephthys, Neith, and Selkis, are making a libation for one of the sons of Horus on the right, with four columns of hieroglyphic inscriptions on the left (fig. 2). The box (H. 44.5 cm, W. 45 cm, and D. 42 cm ) is in good condition apart from three fragmented lines on the sides of the box pertaining to Neith, Nephthys, and Isis, and a break in the sloping lid on the Nephthys side. Its provenance was not recorded, but the title of the owner (‘Singer in the interior (of the Temple) of Amun’) suggests it came from Thebes. -

Cwiek, Andrzej. Relief Decoration in the Royal

Andrzej Ćwiek RELIEF DECORATION IN THE ROYAL FUNERARY COMPLEXES OF THE OLD KINGDOM STUDIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT, SCENE CONTENT AND ICONOGRAPHY PhD THESIS WRITTEN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. KAROL MYŚLIWIEC INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY FACULTY OF HISTORY WARSAW UNIVERSITY 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would have never appeared without help, support, advice and kindness of many people. I would like to express my sincerest thanks to: Professor Karol Myśliwiec, the supervisor of this thesis, for his incredible patience. Professor Zbigniew Szafrański, my first teacher of Egyptian archaeology and subsequently my boss at Deir el-Bahari, colleague and friend. It was his attitude towards science that influenced my decision to become an Egyptologist. Professor Lech Krzyżaniak, who offered to me really enormous possibilities of work in Poznań and helped me to survive during difficult years. It is due to him I have finished my thesis at last; he asked me about it every time he saw me. Professor Dietrich Wildung who encouraged me and kindly opened for me the inventories and photographic archives of the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, and Dr. Karla Kroeper who enabled my work in Berlin in perfect conditions. Professors and colleagues who offered to me their knowledge, unpublished material, and helped me in various ways. Many scholars contributed to this work, sometimes unconsciously, and I owe to them much, albeit all the mistakes and misinterpretations are certainly by myself. Let me list them in an alphabetical order, pleno titulo: Hartwig -

The Bulletin of the Australian Centre for Egyptology Volume 1, 1990

THE BULLETIN OF THE AUSTRALIAN CENTRE FOR EGYPTOLOGY AU rights reserved ISSN: 1035-7254 Published by: The Australian Centre for Egyptology Macquarie University, North Ryde, N.S.W. 2109, Australia Printed by: Adept Printing Pty. Ltd. 13 Clements Avenue, Bankstown, N.S.W. 2200, Australia CONTENTS Foreword 5 Akhenaten and the Amarna Period Juliette Bentley 7 Queen Hetepheres I Gae Callender 25 An Early Treaty of Friendship Between Egypt and Hatti Dorrie Davis 31 Memphis 1989 - The Ptah Temple Complex Lisa Giddy 39 Excavations at Ismant El-Kharab in the Dakhleh Oasis Colin A. Hope 43 Saqqara Excavations Shed New Light on Old Kingdom History Naguib Kanawati 55 The Cult of Min in the Third Millenium B.C. Ann McFarlane 69 Nagc EI Mashayikh - The Ramesside Tombs Boyo Ockinga 77 The Place of Magic in the Practice of Medicine in Ancient Egypt Jim Walker 85 News From Egypt 97 3 QUEEN HETEPHERES I Gae Callender Macquarie University Queen Hetepheres I lived during Dynasty IV, from the time of Sneferu to Khufu. What little we know about her comes from her tomb: G 7000x at Giza. This tomb lies close to the pyramid of her son, Khufu, in the eastern sector of the Giza cemetery (see Figure. 1). The queen's tomb, which is really only a burial chamber at the foot of a 27 metre deep shaft, close to the pyramid of Khufu, was discovered by the Harvard-Boston team, led by Dr. George Reisner, in 1925. The tomb had not been plundered by robbers, and its preservation was certainly due to the fact that the entrance to the burial shaft had been concealed in the pavement in front of Khufu's mortuary temple. -

Lindon Smith Joseph Aegyptologe Maler

Joseph Lindon Smith *11. Oktober 1863 Pawtucket, + 18. Oktober 1950 Rhode Island Gästebücher Bd. III Aufenthalt Schloss Neubeuern: Juli 1894 / 3.- 8. Oktober 1897 / Oktober 1899 (C) http://www.aaa.si.edu/exhibits/pastexhibits/vacations/wall4_2.htm Joseph Lindon Smith war ein amerikanischer Maler, der vor allem für seine außerordentlich treuen und lebendigen Darstellungen von Altertümern, insbesondere ägyptischen Grabreliefs, bekannt war. Er war Gründungsmitglied der Kunstkolonie in Dublin, New Hampshire. Smith wurde am 11. Oktober 1863 in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, als Sohn von Henry Francis Smith, einem Holzfäller, und Emma Greenleaf Smith geboren. Er interessierte sich für ein Kunststudium und wurde an der Schule des Museum of Fine Arts in Boston unterrichtet. Im Herbst 1883 segelte Smith mit seinem Freund und Kommilitonen an der Schule des Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Frank Weston Benson, nach Paris. Sie teilten sich eine Wohnung in Paris, während sie an der Académie Julian (1883–85) bei William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jules Joseph Lefebvre und Gustave Boulanger studierten. "Der Geräuschpegel in der Académie Julian ist immer konstant: das Kratzen von Bänken auf dem Boden als Künstlerjockey für eine bessere Sicht auf das Modell, das lebhafte Geplänkel von Dutzenden junger Männer in drei oder vier verschiedenen Sprachen. Die Luft im Studio ist warm und voller Düfte von Leinöl und Terpentin, feuchten Wolljacken und dem Rauch von Pfeifen und Zigaretten. In einer Ecke konzentriert sich Frank Benson darauf, den letzten Schliff zu geben Ein Porträt des Modells, eines hageren alten Mannes. Er wischt sich mit dem Pinsel über seinen Kittel und winkt seinem Freund Joseph Lindon Smith zu. -

Does Substrate Colour Affect the Visual Appearance of Gilded Medieval Sculptures? Part I: Colorimetry and Interferometric Microscopy of Gilded Models

Does substrate colour affect the visual appearance of gilded medieval sculptures? Part I: Colorimetry and interferometric microscopy of gilded models Qing Wu ( [email protected] ) Universitat Zurich https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5337-0396 Meret Hauldenschild Hochschule der Kunste Bern Benedikt Rösner Paul Scherrer Institut Tiziana Lombardo Swiss National Museum Katharina Schmidt-Ott Swiss National Museum Benjamin Watts Paul Scherrer Institut Frithjof Nolting Paul Scherrer Institut David Ganz University of Zurich Research article Keywords: medieval, gilding, surface, colour, substrate, colorimetry, interferometric microscopy Posted Date: October 23rd, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-66102/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on November 23rd, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494- 020-00463-3. Page 1/17 Abstract In the history of medieval gilding, a common view has been circulated for centuries that the substrate colour can inuence the visual appearance of a gilded surface. In order to fully understand the correlation between the gilding substrate and the colour appearance of the gold leaf laid above, in this paper (Part I) analytical techniques such as colorimetry and interferometric microscopy are implemented on models made from modern gold leaves. This study demonstrates that the substrate colour is not perceptible for gold leaf of at least 100 nm thickness, however the surface burnishing can greatly alter the visual appearance of a gold surface, and the quality of the burnishing is dependent on the substrate materials. -

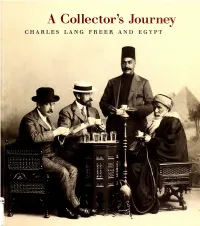

A Collector's Journey : Charles Lang Freer and Egypt / Ann C

A Collector's Journ CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT A Collector's Journey "I now feel that these things are the greatest art in the world," wrote Charles Lang Freer, to a close friend. ". greater than Greek, Chinese or Japanese." Surprising words from the man who created one of the finest collections of Asian art at the turn of the century and donated the collection and funds to the Smithsonian Institution for the construction of the museum that now bears his name, the Freer Gallery of Art. But Freer (1854-1919) became fascinated with Egyptian art during three trips there, between 1906 and 1909, and acquired the bulk of his collection while on site. From jewel-like ancient glass vessels to sacred amulets with supposed magical properties to impressive stone guardian falcons and more, his purchases were diverse and intriguing. Drawing on a wealth of unpublished letters, diaries, and other sources housed in the Freer Gallery of Art Archives, A Collectors Journey documents Freer's expe- rience in Egypt and discusses the place Egyptian art occupied in his notions of beauty and collecting aims. The author reconstructs Freer's journeys and describes the often colorful characters—collectors, dealers, schol- ars, and artists—he met on the way. Gunter also places Freer's travels and collecting in the broader context of American tourism and interest in Egyptian antiquities at the time—a period in which a growing number of Americans, including such financial giants as J. Pierpont Morgan and other Gilded Age barons, were collecting in the same field. A Collector's Journey CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT A Collector's Journey CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT ) Ann C.