The Administration of Justice in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Virginia

NORTHERN VIRGINIA SALAMANDER RESORT & SPA Middleburg WHAT’S NEW American soldiers in the U.S. Army helped create our nation and maintain its freedom, so it’s only fitting that a museum near the U.S. capital should showcase their history. The National Museum of the United States Army, the only museum to cover the entire history of the Army, opened on Veterans Day 2020. Exhibits include hundreds of artifacts, life-sized scenes re- creating historic battles, stories of individual soldiers, a 300-degree theater with sensory elements, and an experiential learning center. Learn and honor. ASK A LOCAL SPITE HOUSE Alexandria “Small downtown charm with all the activities of a larger city: Manassas DID YOU KNOW? is steeped in history and We’ve all wanted to do it – something spiteful that didn’t make sense but, adventure for travelers. DOWNTOWN by golly, it proved a point! In 1830, Alexandria row-house owner John MANASSAS With an active railway Hollensbury built a seven-foot-wide house in an alley next to his home just system, it’s easy for to spite the horse-drawn wagons and loiterers who kept invading the alley. visitors to enjoy the historic area while also One brick wall in the living room even has marks from wagon-wheel hubs. traveling to Washington, D.C., or Richmond The two-story Spite House is only 25 feet deep and 325 square feet, but on an Amtrak train or daily commuter rail.” NORTHERN — Debbie Haight, Historic Manassas, Inc. VIRGINIA delightfully spiteful! INSTAGRAM- HIDDEN GEM PET- WORTHY The menu at Sperryville FRIENDLY You’ll start snapping Trading Company With a name pictures the moment features favorite like Beer Hound you arrive at the breakfast and lunch Brewery, you know classic hunt-country comfort foods: sausage it must be dog exterior of the gravy and biscuits, steak friendly. -

Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves Mary Geraghty College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Geraghty, Mary, "Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625788. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-jk5k-gf34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOMESTIC MANAGEMENT OF WOODLAWN PLANTATION: ELEANOR PARKE CUSTIS LEWIS AND HER SLAVES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary Geraghty 1993 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts -Ln 'ln ixi ;y&Ya.4iistnh A uthor Approved, December 1993 irk. a Bar hiara Carson Vanessa Patrick Colonial Williamsburg /? Jafhes Whittenburg / Department of -

POHICK POST Pohick Episcopal Church

POHICK POST Pohick Episcopal Church 9301 Richmond Highway • Lorton, VA 22079 Telephone: 703-339-6572 • Fax: 703-339-9884 January 2021 Expecting that From The Rector we won’t suffer finan- The Reverend cial effects from this Dr. Lynn P. Ronaldi year of social distanc- ing and shut-down is clearly unrealistic. So “May the God of hope fill you is expecting that our with all joy and peace as you trust in him, children will be back so that you may overflow with hope in school, or that we by the power of the Holy Spirit.” will be back inside our Rev. Lynn read the Christmas Story Romans 15:13 church in the next few during Pohick’s first Live Nativity. months. For some of In these early days of us who have lost loved ones, life will never return to 2021, we give thanks that the way it was. It’s unrealistic to expect that we will 2020 is over, and that we have “go back to normal” soon - if ever! a vaccine! We hope that we What is both realistic and also based on the prom- are in the final stretch of these ise of the Resurrection, is the expectation that our disruptive, Lord has, can, and will redeem disordered, our suffering and loss. A more re- downright alistic expectation is trusting that discouraging the Risen Lord is doing some- The Lewis Family portrayed times. We ex- thing new! As we trust in Him, the Holy Family during pect that the we can discover the elusive peace the Live Nativity. -

Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment As Justice of the Peace

Catholic University Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Winter 1996 Article 2 1996 Marbury's Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment as Justice of the Peace. David F. Forte Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation David F. Forte, Marbury's Travail: Federalist Politics and William Marbury's Appointment as Justice of the Peace., 45 Cath. U. L. Rev. 349 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol45/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES MARBURY'S TRAVAIL: FEDERALIST POLITICS AND WILLIAM MARBURY'S APPOINTMENT AS JUSTICE OF THE PEACE* David F. Forte** * The author certifies that, to the best of his ability and belief, each citation to unpublished manuscript sources accurately reflects the information or proposition asserted in the text. ** Professor of Law, Cleveland State University. A.B., Harvard University; M.A., Manchester University; Ph.D., University of Toronto; J.D., Columbia University. After four years of research in research libraries throughout the northeast and middle Atlantic states, it is difficult for me to thank the dozens of people who personally took an interest in this work and gave so much of their expertise to its completion. I apologize for the inevita- ble omissions that follow. My thanks to those who reviewed the text and gave me the benefits of their comments and advice: the late George Haskins, Forrest McDonald, Victor Rosenblum, William van Alstyne, Richard Aynes, Ronald Rotunda, James O'Fallon, Deborah Klein, Patricia Mc- Coy, and Steven Gottlieb. -

The Administration of Justice in the Counties of Fairfax and Alexandria

The Administration ofJustice in the Counties of Fairfax and Alexandria (Arlington) and the City of Alexandria Part I By RoBERT NELSON ANDERSON* * * * * NoTE: The purpose of this article is to point out the courts of law that would have been available to a person residing in the area now known as Arlington County at any period of time from Colonial days to the present. Hence the narra tive stops as far as Fairfax County is concerned when jurisdiction was taken by the Federal Government over the Virginia portion of the District of Columbia in r8or and as far as Alexandria City is concerned when a court house was erected in Alex andria County (now Arlington) in r89i, thereby locating the County's judicial center within its own borders. Other than the courts that existed in the Virginia portion of the District of Columbia, this article is not intended to cover the Federal courts. * * * * In the year 1634, twenty-seven yea rs after the landing of the English colo nists at Jamestown, the various settlements that had been made over the new territory were by an act of the General Assembly of the province organized into eight distinct shires, or counties, as follows: The Isle of Wight, west of t)i.e James River; Henrico, Warwick, Elizabeth City, James City, and Charles City, between the James and Rappahannock Rivers; York; and Northampton on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay. In 1648, the isolated settlements that had been made at Chicacoan,1 on the shores of the lower Potomac, were organized into another county, named Northumberland,2 the boundaries of which were defined as embracing all that territory lying between the Potomac and Rappahannock Rivers and extending from the Chesapeake Bay to the headwaters of such rivers high up in the Allegheny Mountains. -

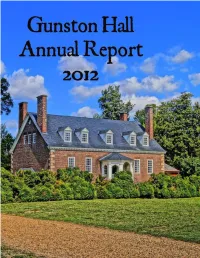

Annual Report 2012.Pub

FFFROM THE FIRST REGENT OVER THE PAST EIGHT YEARS , the plantation of George Mason enjoyed meticulous restoration under the directorship of David Reese. Acclaim was univer- sal, as the mansion and outbuildings were studied, re- paired, and returned to their original stature. Contents In response to the voices of community, staff, docents From the First Regent 2 and the legislature, the Board of Regents decided in early 2012 to focus on programming and to broadened interac- 2012 Overview 3 tion with the public. The consulting firm of Bryan & Jordan was engaged to lead us through this change. The work of Program Highlights 4 the Search Committee for a new Director was delayed while the Regents and the Commonwealth settled logistics Education 6 of employment, but Acting Director Mark Whatford and In- terim Director Patrick Ladden ably led us and our visitors Docents 7 into a new array of activity while maintaining the program- ming already in place. Archaeology 8 At its annual meeting in October the Board of Regents adopted a new mission statement: Seeds of Independence 9 To utilize fully the physical and scholarly resources of Museum Shop 10 Gunston Hall to stimulate continuing public exploration of democratic ideals as first presented by Staff & GHHIS 11 George Mason in the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights. Budget 12 The Board also voted to undertake a strategic plan for the purpose of addressing the new mission. A Strategic Funders and Donors 13 Planning Committee, headed by former NSCDA President Hilary Gripekoven and comprised of membership repre- senting Regents, staff, volunteers, and the Commonwealth, promptly established goals and working groups. -

Winter Issue: Richard Ratcliffe: the Founder

"Preserving the Past. Protecting the Future." the Protecting Past. the "Preserving Volume 3, Issue 1 Winter 2005 Richard Ratcliffe: The Founder Historic Fairfax City, Inc. "Fare Fac - Say Do" Executive Officers Hildie D. Carney President Ann F. Adams Vice-Pres. by William Page Johnson, II Hon. John E. Petersen Treasurer One of the most influential and often overlooked Karen M. Stevenson Secretary figures in the early history of Fairfax is Richard Ratcliffe. Norma M. Darcey Director Born in Fairfax County, Virginia about 1751, Richard was Fairfax, VA 22030 VA Fairfax, Patricia A. Fabio Director Kevin M. Frank Director the son of John Ratcliffe and Ann (Smith) Moxley, the widow 10209 Main Street Main 10209 Michael D. Frasier Director of Thomas Moxley. John Ratcliffe, was a contemporary of G. William Jayne Director Hildie Carney, President Carney, Hildie Hon. Wm. Page Johnson, II Director both George Mason and George Washington. In fact, Return Address - Historic Fairfax City, Inc. City, Fairfax Historic - Address Return Andrea J. Loewenwarter Director Washington recorded the Ratcliffe’s in his diary: “Mrs. Bonnie W. McDaniel Director 1 David L. Meyer Director Ratcliffe and her son came to dinner.” Bradley S. Preiss Director Hon. John H. Rust, Jr. Director Betsy K. Rutkowski Director From 1771 until his death in 1825 Richard Ratcliffe served variously Eleanor D.Schmidt Director as the Fairfax County sheriff, coroner, justice, patroller, overseer of the Dolores B. Testerman Director Edward C. Trexler, Jr. Director poor, constable, commissioner of the revenue, jail inspector, superintendent Ellen R. Wigren Director of elections, candidate for the Virginia General Assembly and designer and The Newsletter of Sidney H. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1942, Volume 37, Issue No. 3

G ^ MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. XXXVII SEPTEMBER, 1942 No. } BARBARA FRIETSCHIE By DOROTHY MACKAY QUYNN and WILLIAM ROGERS QUYNN In October, 1863, the Atlantic Monthly published Whittier's ballad, "' Barbara Frietchie." Almost immediately a controversy arose about the truth of the poet's version of the story. As the years passed, the controversy became more involved until every period and phase of the heroine's life were included. This paper attempts to separate fact from fiction, and to study the growth of the legend concerning the life of Mrs. John Casper Frietschie, nee Barbara Hauer, known to the world as Barbara Fritchie. I. THE HEROINE AND HER FAMILY On September 30, 1754, the ship Neptune arrived in Phila- delphia with its cargo of " 400 souls," among them Johann Niklaus Hauer. The immigrants, who came from the " Palatinate, Darmstad and Zweybrecht" 1 went to the Court House, where they took the oath of allegiance to the British Crown, Hauer being among those sufficiently literate to sign his name, instead of making his mark.2 Niklaus Hauer and his wife, Catherine, came from the Pala- tinate.3 The only source for his birthplace is the family Bible, in which it is noted that he was born on August 6, 1733, in " Germany in Nassau-Saarbriicken, Dildendorf." 4 This probably 1 Hesse-Darmstadt, and Zweibriicken in the Rhenish Palatinate. 2 Ralph Beaver Strassburger, Pennsylvania German Pioneers (Morristown, Penna.), I (1934), 620, 622, 625; Pennsylvania Colonial Records, IV (Harrisburg, 1851), 306-7; see Appendix I. 8 T. J. C, Williams and Folger McKinsey, History of Frederick County, Maryland (Hagerstown, Md., 1910), II, 1047. -

ICT.I9200I United States Department of the Interior Nationa Service NATIONAL REGISTER of HISTORIC PLACES RE

NFS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) ICT.I9200I United States Department of the Interior Nationa Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RE 1. Name of Property historic name: WASHINGTON BOTTOM FARM other name/site number: Ridgedale 2. Location street & number: Off State Route 28 not for publication: N/A city/town: Springfield vicinity: N/A state: WV county: Hampshire code: 027 zip code: 26763 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CAR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant __ nationally __ statewide x locally. (__ See continuation sheet.) /Cpoo Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal agency and bureau Date In my opinion, theiiproperty __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. (__ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of Certifying Official/Title Date State or Federal agency and bureau Date Washington Bottom Farm Hampshire County* WV Name of Property County and State 4. National Park Service Certification I, hereby certify that this property is: Signature of Keeper Date of Action entered in the National Register See continuation sheet. _ determined eligible for the National Register __ See continuation sheet. _ determined not eligible for the National Register _ removed from the National Register other (explain): 5. -

By Eleanor Lee Templeman Reprinted from the Booklet Prepared for the Visit of the Virginia State Legislators to Northern Virginia, January 1981

THE HERITAGE OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA By Eleanor Lee Templeman Reprinted from the booklet prepared for the visit of the Virginia State Legislators to Northern Virginia, January 1981. The documented history of Northern Virginia goes back to John Smith's written description of his exploration of the Potomac in 1608 that took him to Little Falls, the head of Tidewater at the upper boundary of Arlington Coun ty. Successive charters issued to the Virginia Company in 1609 and 1612 granted jurisdiction over all territory lying 200 miles north and south of Point Comfort, "all that space and circuit of land lying from the seacoast of the precinct aforesaid, up into the land throughout from sea to sea, west and northwest." The third charter of 1612 included Bermuda. The first limitations upon the extent of the "Kingdom of Virginia," as it was referred to by King Charles I, came in 1632 when he granted Lord Baltimore a proprietorship over the part that became Maryland. The northeastern portion of Virginia included one of America's greatest land grants, the Northern Neck Proprietary of approximately six million acres. In 1649, King Charles II, a refugee in France because of the English Civil War, granted to seven loyal followers all the land between the Potomac and Rap pahannock Rivers. (Although the term, "Northern Neck" is usually applied to . that portion south of Fredericksburg, the largest portion is in Northern Virginia.) Charles II, then in command of the British Navy, was about to launch an attack to recover the English throne. His power, however, was nullified by Cromwell's decisive victory at Worcester in 1650. -

Alexandria Lodge No. 39 Alexandria, Virginia 1783-1788

ALEXANDRIA LODGE NO. 39 ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 1783-1788 "THE first movement towards the organization of a Masonic Lodge in Alexandria, Virginia was in the year 1782, when Robert Adam, Michael Ryan, William Hunter, Sr., John Allison, Peter Dow, and Dr. Elisha Cullen Dick, presented a petition to the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, praying for a dispensation or warrant to open a Lodge at Alexandria, under the sanction of that Grand Lodge, and recommending the appointment of Robert Adam, Esq., to the office of Worshipful Master, Col. Michael Ryan, to that of Senior Warden, and William Hunter, to that of Junior Warden. This petition was presented to the Grand Lodge at its Quarterly Communication, held on the 2d day. of September, 1782, and it appearing to the Grand Lodge that "Brother Adam, the proposed Master thereof, had been found to possess his knowledge of Masonry in a clandestine manner,” the said petition was ordered to lie over until the next regular Communication of the Grand Lodge. Adam lived in Annapolis, Maryland when he came to America from Scotland in 1753 at the age of 22. It is thought that he joined a Masonic Lodge of “Moderns” under the St. John’s Grand Lodge while living in Annapolis. Dr. Elisha C. Dick has received his degrees in Masonry in Lodge No. 2 in Philadelphia and apparently took steps to have Adam made a member of that Lodge to satisfy the Grand Lodge. The Grand Lodge convened in extra Communication on the 3rd day of February, 1783, when, "it appearing that since the last Communication of this Grand Lodge that the said Brother Adam has passed through the several steps of Ancient Masonry in Lodge No. -

The Google Challenge to Common Law Myth James Maxeiner University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship Spring 2015 A Government of Laws Not of Precedents 1776-1876: The Google Challenge to Common Law Myth James Maxeiner University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Common Law Commons, Computer Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation A Government of Laws Not of Precedents 1776-1876: The Google Challenge to Common Law Myth, 4 Brit. J. Am. Legal Stud. 137 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A GOVERNMENT OF LAWS NOT OF PRECEDENTS 1776-1876: THE GOOGLE CHALLENGE TO COMMON LAW MYTH* James R. Maxeiner"" ABSTRACT The United States, it is said, is a common law country. The genius of American common law, according to American jurists, is its flexibility in adapting to change and in developing new causes of action. Courts make law even as they apply it. This permits them better to do justice and effectuate public policy in individual cases, say American jurists. Not all Americans are convinced of the virtues of this American common law method. Many in the public protest, we want judges that apply and do not make law.