Acknowledgements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources Policy and Mine Closure in South Africa: the Case of the Free State Goldfields

Resources Policy 38 (2013) 363–372 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Resources Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/resourpol Resources policy and mine closure in South Africa: The case of the Free State Goldfields Lochner Marais n Centre for Development Support, University of the Free State, PO Box 339, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa article info abstract Article history: There is increasing international pressure to ensure that mining development is aligned with local and Received 24 October 2012 national development objectives. In South Africa, legislation requires mining companies to produce Received in revised form Social and Labour Plans, which are aimed at addressing local developmental concerns. Against the 25 April 2013 background of the new mining legislation in South Africa, this paper evaluates attempts to address mine Accepted 25 April 2013 downscaling in the Free State Goldfields over the past two decades. The analysis shows that despite an Available online 16 July 2013 improved legislative environment, the outcomes in respect of integrated planning are disappointing, Keywords: owing mainly to a lack of trust and government incapacity to enact the new legislation. It is argued that Mining legislative changes and a national response in respect of mine downscaling are required. Communities & 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Mine closure Mine downscaling Local economic development Free State Goldfields Introduction areas were also addressed. According to the new Act, mining companies are required to provide, inter alia, a Social and Labour For more than 100 years, South Africa's mining industry has Plan as a prerequisite for obtaining mining rights. These Social and been the most productive on the continent. -

South Africa)

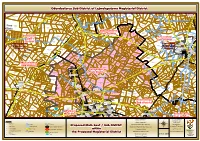

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

Ventersburg Consolidated Prospecting Right Project

VENTERSBURG CONSOLIDATED PROSPECTING RIGHT PROJECT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT Submitted in support of the Prospecting Right and Environmental Authorisation Application Prepared on Behalf of: WESTERN ALLEN RIDGE GOLD MINES (PTY) LTD (Subsidiary of White Rivers Exploration (Pty) Ltd) DMR REFERENCE NUMBER: FS 30/5/1/1/3/2/1/1/10489 EM 18 APRIL 2018 Dunrose Trading 186 (PTY) Ltd T/A Shango Solutions Registration Number: 2004/003803/07 H.H.K. House, Cnr Ethel Ave and Ruth Crescent, Northcliff Tel: +27 (0)11 678 6504, Fax: +27 (0)11 678 9731 VENTERSBURG CONSOLIDATED PROSPECTING RIGHT PROJECT BASIC ASSESSMENT REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT Compiled by: Ms Nangamso Zizo Siwendu Environmental Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 072 669 6250 E-mail: [email protected] Reviewed by: Dr Jochen Schweitzer Principal Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 082 448 2303 E-mail: [email protected] Ms Stefanie Weise Principal Consultant, Shango Solutions Cell: 081 549 5009 E-mail: [email protected] DOCUMENT CONTROL Revision Date Report 1 12 March 2018 Draft Basic Assessment Report and Environmental Management Programme 2 18 April 2018 Final Basic Assessment Report and Environmental Management Programme DISCLAIMER AND TERMS OF USE This report has been prepared by Dunrose Trading 186 (Pty) Ltd t/a Shango Solutions using information provided by its client as well as third parties, which information has been presumed to be correct. Shango Solutions does not accept any liability for any loss or damage which may directly or indirectly result from any advice, opinion, information, representation or omission, whether negligent or otherwise, contained in this report. -

Odendaalsrus VOORNIET E 910 1104 S # !C !C#!C # !C # # # # GELUK 14 S 329 ONRUST AANDENK ZOETEN ANAS DE RUST 49 Ls HIGHLANDS Ip RUST 276 # # !

# # !C # # # ## ^ !C# !.!C# # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C^ # # # # # # # ^ # # ^ # # !C # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# # # !C!C # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # !C # ## # # # # !C ^ # # # # # # # # # ^ # # # #!C # # # # # !C # # #^ # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # !C# ## # # #!C # # # # !C# # #^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # !C # # # ## # # # !C # # # ## # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C# !C # ^ # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #!C # # #^ !C #!C# # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C# ^ ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # !C # #!C # # # # # !C# # # # # !C # # !C## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # # # ## # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ^ !C # # # # # # # # # ^ # # ## # # # # # # # # # # # ## # # # # #!C # !C # # !C # # #!C # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # ### # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # #### # # # !C # ## !C# # # # !C # ## !C # # # # !C # !. # # # # # # # # # # # ## # #!C # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # # #^ # # # # # ## ## # # # # # # # # ^ # !C ## # # # # # # # # # !C# # # # # # # # # # ## # # ## # !C # # !C## # # # ## # !C # ## # # # # # !C # # # # # !C ### # # !C# # #!C # ^ # ^ # !C # # # !C # #!C ## # # # # # # # # ## # # # # # !C## ## # # # # # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # # # # # # !C # # # # # !C ^ # # ## # # # # # # # # -

Criminal Procedure Act 51 of 1977

CRIMINAL PROCEDURE ACT 51 OF 1977 Schedule of commencements relating to magisterial districts amended by magisterial districts and dates Act 122 of 1991 s. 38 (adds s. 62 (f)); Pretoria and Wonderboom: 15 August 1991; Bellville, Brits, s. 41 (a) (adds s. 276 (1) (h)); Bronkhorstspruit, Cullinan, Goodwood, The Cape, Kuils River, s. 41 (b) (adds s. 276 (3)); Mitchells Plain, Simon's Town, Soshanguve, Warmbaths and s. 42 (inserts s. 276A (1)) Wynberg: 20 March 1992; Adelaide, Albany, Alexandria, Barkly West, Bathurst, Bedford, Bloemfontein, Boshof, Bothaville, Botshabelo, Brandfort, Caledon, Calitzdorp, Camperdown, Ceres, Chatsworth, Durban, East London, Fort Beaufort, George, Groblersdal, Hankey, Hennenman, Herbert, Humansdorp, Inanda, Jacobsdal, Kimberley, King William's Town, Kirkwood, Klerksdorp, Knysna, Komga, Koppies, Kroonstad, Ladismith (Cape), Laingsburg, Lindley, Lydenburg, Malmesbury, Middelburg (Transvaal), Montagu, Mossel Bay, Moutse, Nelspruit, Oberholzer, Odendaalsrus, Oudtshoorn, Paarl, Parys, Pilgrim's Rest, Petrusburg, Pietermaritzburg, Pinetown, Port Elizabeth, Potchefstroom, Robertson, Somerset West, Stellenbosch, Strand, Sutherland, Tulbagh, Uitenhage, Uniondale, Vanderbijlpark, Ventersdorp, Vereeniging, Viljoenskroon, Vredefort, Warrenton, Welkom, Wellington, Witbank, White River and Worcester: 1 August 1992; Alberton, Barberton, Belfast, Benoni, Bergville, Bethal, Bethlehem, Bloemhof, Boksburg, Brakpan, Carolina, Coligny, Cradock, Delmas, Dundee, Eshowe, Estcourt, Frankfort, Germiston, Glencoe, Gordonia, Graaff-Reinet, -

Katleho-Winburg District Hospital Complex

KATLEHO / WINBURG DISTRICT HOSPITAL COMPLEX Introduction The Katleho-Winburg District Hospital complex is dedicated to serving the people with the outmost care, We serve the communities of Virginia, Ventersburg, Hennenman and Theunissen. Patients are referred by the clinics in the area of our hospitals, which are level 1 hospitals. In return, we refer patients to Bongani Hospital in Welkom for level 2 care. Please bring the following: UIF Certificate or affidavit from the police station, The Service is free for the following people: • Pensioners please bring proof of receiving pension i.e pension card or proof from the bank • Pregnant women and children under the age of 6 years • Disabled - please bring proof of disability/ doctors certificate Visiting Hours MONDAY- SUNDAY MORNING: 10H00 - 10H15 AFTERNOON: 15H00 - 16H00 NIGHT: 19H00 - 20H00 History of Katleho District Hospital With the Department of Health adopting a Primary Health Care approach as a vehicle for District Health Care Services, Katleho District Hospital was established in 1998 for Virginia catchment area. Katleho District Hospital previously known as Provincial Hospital Virginia, has 140 approved beds. The facility has modern equipment for service delivery at its level of care and is staffed with appropriately qualified and committed personnel. This hospital is governed by a Hospital Board History of Winburg District Hospital With the Department of Health adopting a Primary Health Care approach as a vehicle for District Health Care Services, Winburg District Hospital was established in 1998 for Winburg catchment area. Winburg District Hospital previously known as Provincial Hospital Winburg, has 055 approved beds. The facility has modern equipment for service delivery at its level of care and is staffed with appropriately qualified and committed personnel. -

Correction of Notice

Correction of Notice Correction of the notice placed on 8 February 2018 concerning the interruption of bulk electricity supply to Mathjabeng Local Municipality Eskom hereby notifies all parties who are likely to be materially and adversely affected by its intention to interrupt bulk supply to Matjhabeng Local Municipality on 23 March 2018 and continuing indefinitely. Matjhabeng Local Municipality is currently indebted to Eskom in the amount of R1 742 710 459.06 (one billion, seven hundred and forty two million, seven hundred and ten thousand, four hundred and fifty nine rand and six cents) for the bulk supply of electricity, part of which has been outstanding and in escalation since October 2007 (“the electricity debt”). Eskom Holdings SOC Ltd (“Eskom”) is under a statutory obligation to generate and supply electricity to the municipalities nationally on a financial sustainable basis. Matjhabeng Local Municipality’s breach of its payment obligation to Eskom undermines and placed in jeopardy Eskom’s ability to continue the national supply of electricity on a financial sustainable basis. In terms of both the provisions of the Electricity Regulation Act, 4 of 2006 and supply agreement with Matjhabeng Local Municipality, Eskom is entitled to disconnect the supply of electricity of defaulting municipalities of which Matjhabeng Local Municipality is one, on account of non-payment of electricity debt. In order to protect the national interest in the sustainability of electricity supply, it has become necessary for Eskom to exercise its right to disconnect the supply of electricity to Matjhabeng Local Municipality. Eskom recognises that the indefinite disconnection of electricity supply may cause undue hardship to consumers and members of the community, and may adversely affect the delivery of other services. -

Proposed Hennenman 5 Mw Solar Energy Facility Near Ventersburg, Matjhabeng Local Municipality, Free State

1 Palaeontological specialist assessment: desktop study PROPOSED HENNENMAN 5 MW SOLAR ENERGY FACILITY NEAR VENTERSBURG, MATJHABENG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, FREE STATE John E. Almond PhD (Cantab.) Natura Viva cc, PO Box 12410 Mill Street, Cape Town 8010, RSA [email protected] July 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Bluewave Capital SA (Pty) Ltd is proposing to develop a photovoltaic solar energy facility of approximately 5 MW generation capacities to be located c. 5 km from the town of Hennenman and 10 km northwest of Ventersburg, Free State. The study area near Ventersburg is underlain at depth by Late Permian lacustrine to fluvial sediments of the Lower Beaufort Group / Adelaide Subgroup (Karoo Supergroup) that are extensively intruded by Early Jurassic dolerites of the Karoo Dolerite Suite. These bedrocks are for the most part mantled by Quaternary sands, soils and other superficial deposits of low palaeontological sensitivity. Exposure levels of potentially fossiliferous Karoo sediments are correspondingly very low. No fossil remains have been recorded from the Lower Beaufort Group bedrocks in the region near Ventersburg and these are furthermore extensively baked by dolerite intrusions, compromising their fossil heritage. The overlying Pleistocene dune sands are of low palaeontological sensitivity. The overall impact significance of the proposed Hennenman Solar Energy Facility is consequently rated as LOW as far as palaeontological heritage is concerned. This applies equally to all three site alternatives under consideration. Pending the discovery of significant new fossil remains (e.g. fossil vertebrates, petrified wood) during excavation, no further palaeontological studies or professional mitigation are therefore recommended for this alternative energy project. The Environmental Control Officer (ECO) for the project should be alerted to the potential for, and scientific significance of, new fossil finds during the construction phase of the development. -

Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment

Cultural Heritage Impact Assessment: Phase 1 Investigation of the Proposed Gold Mine Operation by Gold One Africa Limited, Ventersburg Project, Lejweleputswa District Municipality, Matjhabeng Local Municipality, Free State For Project Applicant Environmental Consultant Gold One Africa Limited Prime Resources (Pty) Ltd PO Box 262 70 7th Avenue Corner, Cloverfield & Outeniqua Roads Parktown North Petersfield, Springs Johannesburg, 2193 1566 PO Box 2316, Parklands, 2121 Tel: 011 726 1047 Tel No.: 011 447 4888 Fax: 087 231 7021 Fax No. : 011 447 0355 SAMRAD No: FS 30/5/1/2/2/10036 MR e-mail: [email protected] By Francois P Coetzee Heritage Consultant ASAPA Professional Member No: 028 99 Van Deventer Road, Pierre van Ryneveld, Centurion, 0157 Tel: (012) 429 6297 Fax: (012) 429 6091 Cell: 0827077338 [email protected] Date: April 2017 Version: 1 (Final Report) 1 Coetzee, FP HIA: Proposed Gold Mine Operation, Ventersburg District, Free State Executive Summary This report contains a comprehensive heritage impact assessment investigation in accordance with the provisions of Sections 38(1) and 38(3) of the National Heritage Resources Act (Act No. 25 of 1999) and focuses on the survey results from a cultural heritage survey as requested by Prime Resources (Pty) Ltd. The survey forms part of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the proposed gold mining application in terms of the National Environmental Management Act (Act 107 of 1998). The proposed gold mining operation is situated north west of Ventersburg is located on the Remaining Extent (RE) of the farm Vogelsrand 720, the RE and Portions 1, 2 and 3 of the farm of Klippan 77, the farm La Rochelle 760, Portion 1 of the farm Uitsig 723, and RE and Portion 1 of Whites 747, Lejweleputswa District Municipality, Matjhabeng Local Municipality, Free State Province. -

South African Schools

G) o EMIS NAME OF SCHOOL PRIMARY, ADDRESS OF SCHOOL DISTRICT QUfNTILE LEARNER PER LEARNER PER LEARNER c:p NUMBER SECONDARY 2009 NUMBERS ALLOCATION ALLOCATION ..... o 2000 2009 2009 ..... 2 40808137 LA RIVIERA PF/S Primary LA RIVIERA BULTFONTEIN LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 14 807 o 44908059 LADY GREY PFIS Primary GROOTHOEK WESSElSBRON LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 16 807 I 42506276 lANDSKROON PFIS Primary LANDSKROON KROONSTAD LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 6 807 ~ 40704049 lANDSPRUIT PF/S Primary PAPKUIL VERKEERDEVLEI LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 12 807 44008195 LEBONENG PF/S Primary MOLTENO THEUNISSEN LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 12 807 44412018 LEEUDAM PF/S Primary 49 VIRGINIA LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 17 807 42008029 LEEUDOORNS PF/S • Primary LEEUDOORNS HOOPSTAD LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 8 807 42008107 LEEUKRAAL PF/S Primary LEEUWKRAAL HOOPSTAD LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 14 807 42008043 LEEUKRANS PF/S Primary LEEUKRANS HOOPSTAD LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 7 807 44206046 LEHLOHONOLO PF/S Primary STILLE WONING VENTERSBURG LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 12 807 LEKGALENG PFIS Primary LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 7 807 40808053 LEKKERHOEK PFIS Primary LEKKERHOEK FARM BULTFONTEIN LEJWElEPUTS~~ 01 20 807 (J) 41912005 LEKKERlEWE PF/S Primary LEKKERlEWE HENNENMAN LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 18 807 42008056 lETHOLA PF/S Primary KLiPPAN HOOPSTAD LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 10 807 ~ 40506070 LETLOTlO NALEDI PIS Primary HIGHLANDS FARM BOTHAVILLE LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 1,146 807 ~ (J) 40404071 lETSHEGO PF/S Primary BOSRAND DEAlESVILLE LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 6 807 44908257 LETSIBOLO PIS Primary 444 KGANG STREET WESSELSBRON LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 1,069 807 m6 LOMBARDIE PF/S Prtmary LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 12 807 :D» 44208085 LOOD KLOPPER PF/S Primary MOOIDAM VENTERSBURG LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 15 807 Z 44908201 lOUISEPFIS Primary LOUISE FARM WESSELSBRON LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 17 807 :-! 40404137 LOURENSRUS PF/S Primary LOURENSRUS FARM CHRISTIANA LEJWELEPUTSWA 01 10 807 ... -

Establishment of Small Claims Courts for Welkom, Hennenman, Virginia

GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 6 No. 40752 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 31 MARCH 2017 NO. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT 2017 NO. 304 31 MARCH 2017 304 Small Claims Courts Act (61/1984): Establishment of small claims courts for the areas of Welkom, Hennenman, Virginia, Ventersburg, Odendaalsrus and Theunissen and Withdrawal of Government Notice No. 30 of 24 January 2014 40752 SMALL CLAIMS COURTS ACT, 1984 (ACT NO. 61 OF 1984) ESTABLISHMENT OF SMALL CLAIMS COURTS FOR THE AREAS OF WELKOM, HENNENMAN, VIRGINIA, VENTERSBURG, ODENDAALSRUS AND THEUNISSEN AND WITHDRAWAL OF GOVERNMENT NOTICE NO. 30 OF 24 JANUARY 2014 I, John Harold Jeffery, Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, acting under the power delegated to me by the Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development, under section 2 of the Small Claims Courts Act, 1984 (Act No. 61 of 1984), hereby - (a) (i) establish a Small Claims Court for the adjudication of claims for the area of Welkom, consisting of the district of Welkom; (ii) determine Welkom to be the seat of the said Court; and (iii) determine Welkom to be the place in that area for the holding of sessions of the said Court. (b) (i) establish a Small Claims Court for the adjudication of claims for the area of Hennenman, consisting of the district of Hennenman; (ii) determine Hennenman to be the seat of the said Court; and (iii) determine Hennenman to be the place in that area for the holding of sessions of the said Court. (c) (i) establish a Small Claims Court for the adjudication of claims for the area of Virginia, consisting of the district of Virginia; (ii) determine Virginia to be the seat of the said Court; and (iii) determine Virginia to be the place in that area for the holding of sessions of the said Court. -

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published by Authority Uitgegee op Gesag No. 86 TUESDAY, 04 November 2008 No. 86 DINSDAG, 04 November 2008 No. Index Page PROVINCIAL NOTICE 372 PUBLICATION OF THE RESOURCE TARGETING LIST OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS FOR 2009 2 2 No. 86 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE 4 NOVEMBER 2008 PROVINCIAL NOTICE [No. 372 of2008] PUBLICATION OF THE RESOURCE TARGETING LIST OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS FOR 2009 By virtue of section 16 of the Interpretation Act, 1957 (Act No. 33 of 1957), I, MC Mokitlane, Member of the Executive Council responsible for Education in the Province, hereby publish the resource targeting list of public schools for 2009 as contained in Annexure A. PROVINCE: FREESTATE LISTOF PUBLICORDINARY SCHOOLS FOR 2009 Perleemer PRIMARYI Type of Section QulntJle Leemer Allocetlon EMISNumber Nem. of School SECONDARY School: 21 Address of School Addrss of School Code: DIstr1ct 200i NU,"bers 2008 200& 41811121 AANVOOR PF/S Primary Farm No PO BOX 864 HF=!LBRON 9650 FEZILE DABI 01 5 807 42506090 ABRAHAMSKRAAL PF/S Primary Farm No PO BOX 541 KROONSTAD 9500 FEZILE DABI 01 4 807 44306220 ADELINE MEJE PIS Primary Public No PO BOX 701 VILJOENSKROON 9520 FEZILE DABI 01 1,152 807 41811160 ALICE PF/S Primary Farm No PO BOX 251 HEILBRON 9650 FEZILE DABI 01 14 807 41811271 ALPHAPFIS Primary Farm No PO BOX 12 EDENVILLE 9535 FEZILE DABI 01 9 807 42506122 AMACILIA PFIS Primary Farm No PO BOX 676 KROONSTAD 9500 FE~ILE DABI 01 19 807 41610010 ANDERKANT PFIS Primary Farm No PO BOX 199 FRANKFORT 9830 FEZILE DABI 01