Making Sense of American Popular Song John Spitzer and Ronald G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: a Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Logging Songs of the Pacific Northwest: A Study of Three Contemporary Artists Leslie A. Johnson Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC LOGGING SONGS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST: A STUDY OF THREE CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS By LESLIE A. JOHNSON A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Leslie A. Johnson defended on March 28, 2007. _____________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member ` _____________________________ Karyl Louwenaar-Lueck Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank those who have helped me with this manuscript and my academic career: my parents, grandparents, other family members and friends for their support; a handful of really good teachers from every educational and professional venture thus far, including my committee members at The Florida State University; a variety of resources for the project, including Dr. Jens Lund from Olympia, Washington; and the subjects themselves and their associates. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

"World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump

Document généré le 26 sept. 2021 17:23 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations Brad Klump Canadian Perspectives in Ethnomusicology Résumé de l'article Perspectives canadiennes en ethnomusicologie This article traces the origins and uses of the musical classifications "world Volume 19, numéro 2, 1999 music" and "world beat." The term "world beat" was first used by the musician and DJ Dan Del Santo in 1983 for his syncretic hybrids of American R&B, URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014442ar Afrobeat, and Latin popular styles. In contrast, the term "world music" was DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar coined independently by at least three different groups: European jazz critics (ca. 1963), American ethnomusicologists (1965), and British record companies (1987). Applications range from the musical fusions between jazz and Aller au sommaire du numéro non-Western musics to a marketing category used to sell almost any music outside the Western mainstream. Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Klump, B. (1999). Origins and Distinctions of the "World Music" and "World Beat" Designations. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 19(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014442ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1999 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

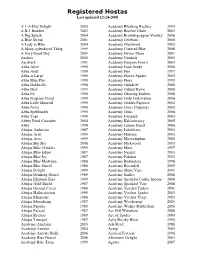

Registered Hostas Last Updated 12-24-2008

Registered Hostas Last updated 12-24-2008 A 1-A-Day Delight 2003 Academy Blushing Recluse 1999 A B-1 Bomber 2002 Academy Bonfire Glade 2003 A Big Splash 2004 Academy Brobdingnagian Viridity 2006 A Blue Streak 2001 Academy Celeborn 2000 A Lady in Blue 2004 Academy Chetwood 2005 A Many-splendored Thing 1999 Academy Cratered Blue 2008 A Very Good Boy 2005 Academy Devon Moor 2001 Aachen 2005 Academy Dimholt 2005 Aardvark 1991 Academy Fangorn Forest 2003 Abba Alive 1990 Academy Faux Sedge 2008 Abba Aloft 1990 Academy Fire 1997 Abba at Large 1990 Academy Flaxen Spades 2002 Abba Blue Plus 1990 Academy Flora 1999 Abba Dabba Do 1998 Academy Galadriel 2000 Abba Dew 1999 Academy Gilded Dawn 2008 Abba Fit 1990 Academy Glowing Embers 2008 Abba Fragrant Cloud 1990 Academy Gold Codswallop 2006 Abba Little Showoff 1990 Academy Golden Papoose 2004 Abba Nova 1990 Academy Grass Clippings 2005 Abba Spellbinder 1990 Academy Grins 2008 Abba Tops 1990 Academy Isengard 2003 Abbey Pond Cascades 2004 Academy Kakistocracy 2005 Abby 1990 Academy Lemon Knoll 2006 Abiqua Ambrosia 1987 Academy Lothlórien 2004 Abiqua Ariel 1999 Academy Mallorn 2003 Abiqua Aries 1999 Academy Mavrodaphne 2000 Abiqua Big Sky 2008 Academy Mirkwood 2003 Abiqua Blue Crinkles 1999 Academy Muse 1997 Abiqua Blue Edger 1987 Academy Nazgul 2003 Abiqua Blue Jay 1987 Academy Palantir 2003 Abiqua Blue Madonna 1988 Academy Redundant 1998 Abiqua Blue Shield 1988 Academy Rivendell 2005 Abiqua Delight 1999 Academy Shiny Vase 2001 Abiqua Drinking Gourd 1989 Academy Smiles 2008 Abiqua Elephant Ears 1999 -

B Clarice K Artist Album Publisher

List of music albums from Bob Witte for the New York Folk Music Society Charlene K-Clarice K B Artist Album Publisher Year $40.00 $210.00 Acrobates et Musiciens Lo Jai Shanachie Records 1987 Anderson, Eric Blue River Wind & Sand Music Anderson, Pink Carolina Blues Man Volume I Prestige/Bluesville Anthology of American Folk Music 6 CD Set, Edited by Harry Smith Smithsonian Folkways $10.00 Assorted Artists The Eastern Shores, Southern Journey Prestige 1960 $15.00 Assorted Artists Music of the World's Greatest Composers Readers Digest Assorted Artists The Roots of Modern Jazz Olympic Records $15.00 Assorted Artists Music of the World's Greatest Composers RCA Victor Assorted Artists Golden Ring Folk-Legacy Assorted Artists The Koto Music of Japan Elektra Records Assorted Artists Drums of the Yoruba of Nigeria Ethnic Folkways Library Assorted Artists Scottish Tradition 2- Music of Western Isles Univ. Edinburgh Assorted Artists Scottish Tradition 4- Shetland Fiddle Music Univ. Edinburgh Assorted Artists Scottish Tradition 6- Gaelic Psalms from Lewis Univ. Edinburgh Assorted Artists Scottish Tradition 7- Callum Ruadh Univ. Edinburgh Assorted Artists Scottish Tradition 8- James Campbell of Kintail Univ. Edinburgh Assorted Artists Scottish Tradition 9- The Fiddler & His Art Univ. Edinburgh Assorted Artists Songs & Dances of Scotland Murray Hill Records Assorted Artists Songs of the Lincoln Brigade Stinson Recordings Assorted Artists Southern Mountain Hoedowns Stinson Recordings Assorted Artists; Fox Hollow 1967 Pitter, Poon, The Rain Came Doon-Vol.I -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Rudimental Classics: 'Hell on the Wabash'

Rudimental Classics ‘Hell on the Wabash’ By Robert J. Damm ell on the Wabash” (with melody) was included in The A number of banjo Moeller Book which, along with “Wrecker’s Daughter tunes, customarily Quickstep,” were described as “two very old favorites that called “jigs,” indicating “Hcan never be improved upon” (p. 63). He also quoted Bruce they were associated as having said, “Without this rudimental instruction we can have only with dances, made indifferent players, comparatively ignorant of the nature of the very their first appearance instrument they play upon” (p. 10). in the 1840s. These As a fife and drum duet, “Hell on the Wabash” first appeared in The banjo tunes were made Drummer’s and Fifer’s Guide (Bruce and Emmett) in 1862. This important widely available to the book provided instruction for both the drum and the fife in score form public in published and included music notation for the camp duty. George Bruce and Dan method books starting Emmett authored the book because they were concerned about the in the 1850s. Dan quality of training received by the field musicians in the army (Olson, p. Emmett included 86). The history of “Hell on the Wabash” touches on both military and 48 banjo tunes in popular music traditions, reflecting the corresponding lives of its authors. an early manuscript George B. Bruce was considered a “first-rate drummer” who had collection he compiled studied with Charles Ashworth (Olson, p. 86). He held the prestigious sometime between post of drum major and principal instructor at the military drumming 1845 and 1860 (there school on Bedloe’s and Governor’s Islands, New York Harbor during the is no date on the Civil War. -

It's Just a Joke: Defining and Defending (Musical) Parody

It’s just a joke: Defining and defending (musical) parody Paul Jewell, Flinders University Jennie Louise, The University of Adelaide ABSTRACT Australia has recently amended copyright laws in order to exempt and protect parodies, so that, as the Hon. Chris Ellison, the then Minster for Justice told the Senate, ‘Australia’s fine tradition of poking fun at itself and others will not be unnecessarily restricted’. It is predicted that there will be legal debates about the definition of parody. But if the law, as the Minister contends, reflects Australian values, then there is a precursor question. Is there anything wrong with parody, such that it should be restricted? In our efforts to define parody, we discover and develop a moral defence of parody. Parody is the imitation of an artistic work, sometimes for the sake of ridicule, or perhaps as a vehicle to make a criticism or comment. It is the appropriation of another’s original work, and therefore, prima facie, exploits the originator. Parody is the unauthorised use of intellectual property, with both similarity to and difference from other misappropriations such as piracy, plagiarism and forgery. Nevertheless, we argue that unlike piracy, plagiarism and forgery, which are inherently immoral, parody is not. On the contrary, parody makes a positive contribution to culture and even to the original artists whose work is parodied. Paul Jewell <[email protected]> is a member of the Ethics Centre of South Australia. He teaches ethics in Disability and Community Inclusion at Flinders University and he is a musician. Jennie Louise is also a member of the Ethics Centre of South Australia. -

Learning Lineage and the Problem of Authenticity in Ozark Folk Music

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1-1-2020 Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music Kevin Lyle Tharp Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tharp, Kevin Lyle, "Learning Lineage And The Problem Of Authenticity In Ozark Folk Music" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1829. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1829 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEARNING LINEAGE AND THE PROBLEM OF AUTHENTICITY IN OZARK FOLK MUSIC A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music The University of Mississippi by KEVIN L. THARP May 2020 Copyright Kevin L. Tharp 2020 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Thorough examination of the existing research and the content of ballad and folk song collections reveals a lack of information regarding the methods by which folk musicians learn the music they perform. The centuries-old practice of folk song and ballad performance is well- documented. Many Child ballads and other folk songs have been passed down through the generations. Oral tradition is the principal method of transmission in Ozark folk music. The variants this method produces are considered evidence of authenticity. Although alteration is a distinguishing characteristic of songs passed down in the oral tradition, many ballad variants have persisted in the folk record for great lengths of time without being altered beyond recognition.