It's Just a Joke: Defining and Defending (Musical) Parody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clean Energy Transition

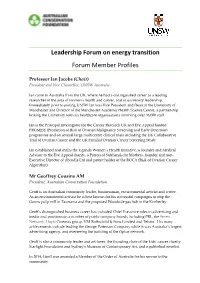

Leadership Forum on energy transition Forum Member Profiles Professor Ian Jacobs (Chair) President and Vice-Chancellor, UNSW Australia Ian came to Australia from the UK, where he had a distinguished career as a leading researcher in the area of women’s health and cancer, and in university leadership. Immediately prior to joining UNSW Ian was Vice President and Dean at the University of Manchester and Director of the Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, a partnership linking the University with six healthcare organisations involving over 36,000 staff. Ian is the Principal Investigator for the Cancer Research UK and Eve Appeal funded PROMISE (Prediction of Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Screening and Early Detection) programme and on several large multicentre clinical trials including the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer and the UK Familial Ovarian Cancer Screening Study. Ian established and chairs the Uganda Women’s Health Initiative, is founder and Medical Advisor to the Eve Appeal charity, a Patron of Safehands for Mothers, founder and non- Executive Director of Abcodia Ltd and patent holder of the ROCA (Risk of Ovarian Cancer Algorithm). Mr Geoffrey Cousins AM President, Australian Conservation Foundation Geoff is an Australian community leader, businessman, environmental activist and writer. As an environmental activist he is best known for his successful campaigns to stop the Gunns pulp mill in Tasmania and the proposed Woodside gas hub in the Kimberley. Geoff’s distinguished business career has included Chief Executive roles in advertising and media and positions on a number of public company boards including PBL, the Seven Network, Hoyts Cinemas group, NM Rothschild & Sons Limited and Telstra. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

OH, PRETTY PARODY: CAMPBELL V. ACUFF-ROSE MUSIC, INC

Volume 8, Number 1 Fall 1994 OH, PRETTY PARODY: CAMPBELL v. ACUFF-ROSE MUSIC, INC. Lisa M. Babiskin* INTRODUCTION For the second time ever, the Supreme Court addressed the affirmative defense of fair use to copyright infringement in the context of parody in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. ~ The unanimous opinion found a parody rap version of Roy Orbison's song "Oh, Pretty Woman" by the group 2 Live Crew could be a fair use within the exceptions to the protections of the Copyright Act of 1976. 2 The fair use defense is an inconsistent and confusing area that has been called "the most trouble- some [issue] in the whole law of copyright. "3 The Campbell decision helps preserve the flexible, case-by-case analysis intended by Congress and recognizes the value of parody both as a form of social criticism and catalyst in literature. The decision affords wide latitude to parodists, emphasizing the irrelevance of the judge's personal view of whether the parody is offensive or distasteful. It is unclear whether future courts will interpret this holding to be limited to fair use of parody in the context of song, or whether they will construe it more broadly to confer substantial freedom to parodists of all media. It is also unclear what effect this decision will have on the music industry's practice of digital sampling. This article will review the historical background of fair use in the context of parody and the case law preceding the Supreme Court's decision. A detailed discussion of the lower courts' decisions will be followed by analysis of the Supreme Court's decision and its implications for the future. -

Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected]

Boston College Law Review Volume 59 | Issue 6 Article 2 7-11-2018 Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lee, Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases, 59 B.C.L. Rev. 1873 (2018), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol59/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAIR USE AVOIDANCE IN MUSIC CASES EDWARD LEE INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1874 I. FAIR USE’S RELEVANCE TO MUSIC COMPOSITION ................................................................ 1878 A. Fair Use and the “Borrowing” of Copyrighted Content .................................................. 1879 1. Transformative Works ................................................................................................. 1879 2. Examples of Transformative Works ............................................................................ 1885 B. Borrowing in Music Composition ................................................................................... -

Business Ethics Study

The 2009 Annual Business and Professions Study business ethics study St James Ethics Centre Beaton Consulting 2009 Annual Business and Professions Study: Business Ethics Study Foreword This report has been produced at a pivotal point in history. The global community is faced by a conjunction of challenges so grave as to justify being considered ‘crises’. The list includes some obvious issues – climate change caused by global warming, world-wide recession, a global food crisis affecting the most vulnerable. However, there is something less obvious that we should attend to - there is also a crisis of confidence; in our principal institutions, their legitimacy and their leadership. Until this deeper issue is acknowledged and addressed our latent capacity to resolve the more obvious issues will falter for want of conviction. Barack Obama sought to identify one dimension of this deeper problem when, prior to his inauguration as President, he sought to indentify the principal factors that had brought the US economy to its knees. This crisis did not happen solely by some accident of history or normal turn of the business cycle, and we won’t get out of it by simply waiting for a better day to come, or relying on the worn-out dogmas of the past. We arrived at this point due to an era of profound irresponsibility that stretched from corporate boardrooms to the halls of power in Washington, DC. For years, too many Wall Street executives made imprudent and dangerous decisions, seeking profits with too little regard for risk, too little regulatory scrutiny, and too little accountability. -

Music Sampling and Copyright Law

CACPS UNDERGRADUATE THESIS #1, SPRING 1999 MUSIC SAMPLING AND COPYRIGHT LAW by John Lindenbaum April 8, 1999 A Senior Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My parents and grandparents for their support. My advisor Stan Katz for all the help. My research team: Tyler Doggett, Andy Goldman, Tom Pilla, Arthur Purvis, Abe Crystal, Max Abrams, Saran Chari, Will Jeffrion, Mike Wendschuh, Will DeVries, Mike Akins, Carole Lee, Chuck Monroe, Tommy Carr. Clockwork Orange and my carrelmates for not missing me too much. Don Joyce and Bob Boster for their suggestions. The Woodrow Wilson School Undergraduate Office for everything. All the people I’ve made music with: Yamato Spear, Kesu, CNU, Scott, Russian Smack, Marcus, the Setbacks, Scavacados, Web, Duchamp’s Fountain, and of course, Muffcake. David Lefkowitz and Figurehead Management in San Francisco. Edmund White, Tom Keenan, Bill Little, and Glenn Gass for getting me started. My friends, for being my friends. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction.....................................................................................……………………...1 History of Musical Appropriation........................................................…………………6 History of Music Copyright in the United States..................................………………17 Case Studies....................................................................................……………………..32 New Media......................................................................................……………………..50 -

Australian Ethics

AUSTRALIAN ETHICS DECEMBER 2013 AUSTRALIAN APPLIED ETHICS PRESIDENT’S REPORT ASSOCIAITON FOR PROFSSIONAL AND ETHICAL REFLECTIONS E T H I C S : O N MEANNESS APPLIED AND Hugh Breakey PROFESSIONAL Business Meanness is a common occurrence. It ‘contempt’ and ‘cruelty’. Even here, his forms part of the social backdrop in Education treatment is revealing. Hobbes holds which we all live, play and work. Most Engineering that these emotions arise from being of us, I think, can think of examples of Environment insensible to others’ calamities—an mean behaviour we have witnessed, Law insensitivity he thinks proceeds from and many of us would know someone Medical one’s own security. For Hobbes does we think of as ‘having a mean streak’. not conceive it possible ‘that any man Nursing should take pleasure in other men’s Police Yet meanness is not a topic that gar- great harms’ purely for its own sake. Public Policy ners much ethical attention. Out of As I read him, Hobbes first tries to pre- Public Sector curiosity, I recently searched a few academic databases for works on sent cruelty as an instance of insensi- Social Work meanness. Even in the context of psy- tivity (which it is not), and then tries to Teaching chology there was surprisingly little— confect ‘ends’ being served by the cru- most of it about school-age children. elty, so as to deny the possibility—the INSIDE THIS I S- In terms of philosophical or ethical very conceivability—of someone inflict- SUE: analysis, there was almost nothing. ing harm for the sheer pleasure of it. -

This Rough Magic a Peer-Reviewed, Academic, Online Journal Dedicated to the Teaching of Medieval and Renaissance Literature

This Rough Magic A Peer-Reviewed, Academic, Online Journal Dedicated to the Teaching of Medieval and Renaissance Literature 'Cheer Up Hamlet!': Using Shakespearean Burlesque to Teach the Bard Author(s): Kendra Preston Leonard Reviewed Work(s): Source: This Rough Magic, Vol. 4, No. 1, (June, 2013), pp. 1-20. Published by: www.thisroughmagic.org Stable URL: http://www.thisroughmagic.org/leonard%20essay.html _____________________________________________________________________________________________ “'Cheer Up Hamlet!': Using Shakespearean Burlesque to Teach the Bard” by Kendra Preston Leonard In his book Not Shakespeare: Bardolatry and Burlesque in the Nineteenth Century, Richard Schoch demonstrates the ways in which Shakespeare’s works were frequently burlesqued in the music halls of the nineteenth century: through parodies directly adapting Shakespearean playtexts; by newly created works that sent up Shakespearean conventions; and in song and dance. Musical performances often combined traditional texts with popular songs or offered up new tunes to explicate or parody the actions or particular scenes in a play, usually in conjunction with some satire aimed at the leading actors and/or politicians of the day. By these means, the plotlines and characters of Shakespeare’ s plays were made widely known, even among non-theatre-going populations, those with only basic educations, and even the illiterate. With the disappearance of vaudeville and other live variety theatre in the twentieth century, however, fully staged burlesques of Shakespeare have mostly faded from view, with perhaps the exception of The Reduced Shakespeare Company’s “Complete Works” show. While a few films, such as Strange Brew (1983), engage in outright Shakespearean burlesque, most popular recent culture burlesquing of 1 / TRM, June 2013 Shakespeare has occurred on television and the internet, often using song as a vehicle parodying the plays, thus combining the satirical and musical elements of traditional burlesque. -

Visiting Artists: Mary Reid Kelley & Patrick Kelley

Visiting Artists: Mary Reid Kelley & Patrick Kelley Monday, March 27, 6:30p Sleeper Auditorium About the Kelleys Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley are a husband-and-wife collaborative duo whose work collides video, performance, painting and writing. Their highly theatrical vignettes performed by the duo feature her scripts, painted sets and costumes and his videography and editing to explore gender, class, and social norms within history, art, and literature. The artists’ use wordplay, punning and rhyme as a humorous and incisive means of deconstructing how history is written and represented. Their short films focus on historical moments of social upheaval, often uncovering the stories and voices of historically underrepresented figures. Female protagonists such as nurses, prostitutes, and factory workers relate to their larger social histories through philosophical references, euphemisms and bawdy puns, all set within the parameters of rhyming verse. Mary Reid Kelley earned a BA from St. Olaf College and an MFA from Yale University. She is the recipient of the MacArthur Foundation Grant, has received awards from the American Academy in Rome, the Rema Hort Mann Foundation, and the College Art Association. Major exhibitions include Salt Lake Art Center, SITE Santa Fe, Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, and ZKM Museum of Contemporary Art in Karlsruhe, Germany. Patrick Kelley earned a BFA from St. Olaf College and an MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art. He has taught Photography, Video and New Media courses at the University of Minnesota, St. Olaf College, St. Mary’s College of Maryland, and Skidmore College in New York. His works have shown at the Bibliothèque Publique d’Information-Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Germany, and the Minnesota Museum of American Art. -

Learn Everything That Facebook Knows About You

Intelligent Robots To Power China’s Factories As a Technocracy, China seeks maximum efficiency and maximum human displacement. The policies, coupled with draconian social engineering, is anti-human as it eliminates human values and dignity. ⁃ TN Editor Robots powered by artificial intelligence are set to replace Chinese factory workers in a move aimed at boosting the manufacturing industry which has been hit hard by a rise in wages. The machines which are capable of making, assembling and inspecting goods on production lines have already been rolled out, with one factory laying off 30 workers to make way for the robots. The robots were displayed at China’s Hi-Tech fair in Shenzhen earlier this month, an annual event which showcases new development ideas with the aim of driving growth in a number industries. But the news has annoyed Washington as it is expected to put international competitors at a disadvantage, as the two countries’s bitter trade war continues to escalate. Speaking to the Financial Times, Sabrina Li, a senior manager at IngDan, said: “We incubated this platform so we can meet the (Made in China 2025) policy. “One noodle factory was able to dismiss 30 people, making it more productive and efficient.” Giving the suffering manufacturing industry a leg up is a key part of the Chinese government’s Made in China 2025 policy. Zhangli Xing, deputy manager of Suzhou Govian Technology which sells the quality control robots, said they are more reliable than human labour. Mr Xing said : “A person looking by eye would take 5-6 seconds for each object, versus 2-3 seconds by machine. -

38.3. Ethics and Professional Practice

Ethics and Professional Practice Core Body of Knowledge for the Generalist OHS Professional Second Edition, 2019 38.3 February 2019 Copyright notice and licence terms Copyright (2019) Australian Institute of Health & Safety (AIHS), Tullamarine, Victoria, Australia This work is copyright and has been published by the Australian Institute of Health & Safety (AIHS). Except as may be expressly provided by law and subject to the conditions prescribed in the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth of Australia), or as expressly permitted below, no part of the work may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, microcopying, digital scanning, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission of the AIHS. You are free to reproduce the material for reasonable personal, or in-house, non-commercial use for the purposes of workplace health and safety as long as you attribute the work using the citation guidelines below and do not charge fees directly or indirectly for use of the material. You must not change any part of the work or remove any part of this copyright notice, licence terms and disclaimer below. A further licence will be required and may be granted by the AIHS for use of the materials if you wish to: • reproduce multiple copies of the work or any part of it • charge others directly or indirectly for access to the materials • include all or part of the materials in advertising of a product or services or in a product for sale • modify the materials in any form, or • publish the materials. -

Musical Plagiarism: a True Challenge for the Copyright Law

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 25 Issue 1 Fall 2014 Article 2 Musical Plagiarism: A True Challenge for the Copyright Law Iyar Stav Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Iyar Stav, Musical Plagiarism: A True Challenge for the Copyright Law, 25 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 1 (2014) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol25/iss1/2 This Lead Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stav: Musical Plagiarism: A True Challenge for the Copyright Law MUSICAL PLAGIARISM: A TRUE CHALLENGE FOR THE COPYRIGHT LAW Iyar Stav* ABSTRACT The interface of law and music has always appearedunnatural. While the law aims to provide certainty and order, music is more often observed as a field which operates in a boundary-less sphere. For that reason, the endeavor to treat purely musical is- sues with clear, conclusive and predeterminedlegal rules has been perceived as a fairly complicated task. Nevertheless, while music has become a prospering business, and musical disputes have been revolving around growing amounts of money, the law was re- quired to step in and provide clear standards according to which these disputes should be settled. The courts in USA and UK have established and developed several doctrines intended to set a uni- fied framework for assessing the extent of similarities between an original work and an allegedly later infringing work.