Rethinking the Henge Monuments of the British Isles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

BA0063 2013-001 Radial Leaded Capacitor Assembly Location Change Notification Jan 13 Final

Syfer Technology Limited Old Stoke Road Arminghall, Norwich, Norfolk NR14 8SQ England Tel: +44 (0)1603 723347 Fax +44 (0)1603 723301 Email: [email protected] Web: www.syfer.com Anglia Sandall Road Wisbech Cambridgeshire PE13 2PS United Kingdom BA0063 February 2013 PCN reference: 2013/01 Subject: Radial Leaded Capacitor Assembly Location Change Dear Customer, Syfer Technology Ltd has been manufacturing radial leaded capacitors at our UK manufacturing facility from the early 1980s. Due to facility space requirements needed to develop and manufacture new products, it has been decided to sub-contract the radial assembly process. Ceramic Chip Capacitor Encapsulation Material Lead to Chip Capacitor Solder Joint Lead Fig. 1. Radial Capacitor Construction Diagram The critical part of the radial component (the ceramic chip capacitor) will still be manufactured, electrically tested and inspected by Syfer. Registered Office: Old Stoke Road Arminghall, Norwich NR14 8SQ England Registered in England: No 2092166 (FA4/971/1) The radial assembly process including soldering leads onto the chip capacitor, encapsulation, print and radial electrical test will be conducted by the sub-contractor. The sub-contractor is certified to ISO9001 and has a proven history of manufacturing and supplying radial leaded capacitors. Syfer has conducted reliability tests on components manufactured by the sub-contractor as part of qualification and ongoing monitoring requirements. The change in location for the radial leaded capacitor assembly does not affect component specifications (including dimensional, performance or reliability) and, as such, there is no change to the Syfer part number. Radial leaded capacitors manufactured by the sub-contractor will gradually be phased into customer supply from March 2013. -

Stonehenge Bibliography

Bibliography Abbot, M. and Anderson-Whymark, H., 2012. Anon., 2011a, Discoveries provide evidence of Stonehenge Laser Scan: archaeological celestial procession at Stonehenge. On-line analysis report. English Heritage project source available at: 6457. English Heritage Research Report http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/latest/ Series no. 32-2012, available at: 2011/11/25Nov-Discoveries-provide- http://services.english- evidence-of-a-celestial-procession-at- herita ge.org.uk/Resea rch Repo rtsPdf s/032_ Stonehenge.aspx (accessed 2 April 2012). 2012WEB.pdf Anon., 2011b, Stonehenge’s sister? Current Alexander, C., 2009, If the stones could speak: Archaeology, 260, 6–7. Searching for the meaning of Stonehenge. Anon., 2011c, Home is where the heath is. National Geographic, 213.6 (June 2008), Late Neolithic house, Durrington Walls. 34–59. Current Archaeology, 256, 42–3. Allen, S., 2008, The quest for the earliest Anon., 2011d, Stonehenge rocks. Current published image of Stonehinge (sic). Archaeology, 254, 6–7. Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural Anon., 2012a, Origin of some of the Bluestone History Magazine, 101, 257–9. debris at Stonehenge. British Archaeology, Anon., 2006, Excavation and Fieldwork in 123, 9. Wiltshire 2004. Wiltshire Archaeological Anon., 2012b, Stonehenge: sourcing the and Natural History Magazine, 99, 264–70. Bluestones. Current Archaeology, 263, 6– Anon., 2007a, Excavation and Fieldwork in 7. Wiltshire 2005. Wiltshire Archaeological Aronson, M., 2010, If stones could speak. and Natural History Magazine, 100, 232– Unlocking the secrets of Stonehenge. 39. Washington DC: National Geographic. Anon., 2007b, Before Stonehenge: village of Avebury Archaeological and Historical wild parties. Current Archaeology, 208, Research Group (AAHRG) 2001 17–21. -

COMMISSION C4 WORLD HERITAGE and ASTRONOMY 1. Background

Transactions IAU, Volume XXXA Reports on Astronomy 2015-2018 c 2018 International Astronomical Union Piero Benvenuti, ed. DOI: 00.0000/X000000000000000X COMMISSION C4 WORLD HERITAGE AND ASTRONOMY PATRIMOINE MONDIAL ET ASTRONOMIE PRESIDENT Clive Ruggles VICE-PRESIDENT Gudrun Wolfschmidt PAST PRESIDENT N/A ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Roger Ferlet, Siramas Komonjinda, Mikhail Marov, Malcolm Smith COMMISSION C4 WORKING GROUPS Div. C / Commission C4 WG1 Windows to the Universe: High-Mountain Observatories and other Astronomical Sites of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries (Joint with Commission B7) Div. C / Commission C4 WG2 Classical Observatories from the Renaissance to the 20th Century Div. C / Commission C4 WG3 Heritage of Space Exploration Div. C / Commission C4 WG4 Astronomical Heritage in Danger Div. C / Commission C4 WG5 Intangible Heritage (Joint with Commission C1) Div. C / Commission C4 WGAAC Archaeoastronomy and Astronomy in Culture (Joint with Commission C3) TRIENNIAL REPORT 2015-2018 1. Background UNESCO's Astronomy and World Heritage Initiative (AWHI) (whc.unesco.org/en/ astronomy) has existed since 2004 to identify, promote and protect heritage, and potential World Heritage, connected with astronomy. A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between UNESCO and the IAU, under which the IAU undertook to implement the AWHI jointly with UNESCO, was signed in 2008 ahead of the IYA 2009. This commitment now continues indefinitely, UNESCO and the IAU having entered into a wider global partnership. The Astronomy and World Heritage Working Group -

The Origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 the Avebury Henge Is One of the Famous Mega

1 The origins of Avebury 2 1,* 2 2 Q13 Q2Mark Gillings , Joshua Pollard & Kris Strutt 4 5 6 The Avebury henge is one of the famous mega- 7 lithic monuments of the European Neolithic, Research 8 yet much remains unknown about the detail 9 and chronology of its construction. Here, the 10 results of a new geophysical survey and 11 re-examination of earlier excavation records 12 illuminate the earliest beginnings of the 13 monument. The authors suggest that Ave- ’ 14 bury s Southern Inner Circle was constructed 15 to memorialise and monumentalise the site ‘ ’ 16 of a much earlier foundational house. The fi 17 signi cance here resides in the way that traces 18 of dwelling may take on special social and his- 19 torical value, leading to their marking and 20 commemoration through major acts of monu- 21 ment building. 22 23 Keywords: Britain, Avebury, Neolithic, megalithic, memory 24 25 26 Introduction 27 28 Alongside Stonehenge, the passage graves of the Boyne Valley and the Carnac alignments, the 29 Avebury henge is one of the pre-eminent megalithic monuments of the European Neolithic. ’ 30 Its 420m-diameter earthwork encloses the world s largest stone circle. This in turn encloses — — 31 two smaller yet still vast megalithic circles each approximately 100m in diameter and 32 complex internal stone settings (Figure 1). Avenues of paired standing stones lead from 33 two of its four entrances, together extending for approximately 3.5km and linking with 34 other monumental constructions. Avebury sits within the centre of a landscape rich in 35 later Neolithic monuments, including Silbury Hill and the West Kennet palisade enclosures 36 (Smith 1965; Pollard & Reynolds 2002; Gillings & Pollard 2004). -

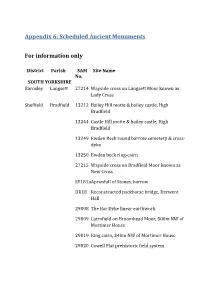

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age Key Sites Southeast Wales – Neolithic

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Key Sites, Southeast Wales, 22/12/2003 Neolithic and earlier Bronze Age Key Sites Southeast Wales – Neolithic and early Bronze Age 22/12/2003 Neolithic Domestic COED-Y-CWMDDA Enclosure with evidence for flint-working Owen-John 1988 CEFN GLAS (SN932024) Late Neolithic hut floor dated to 4110-70 BP. Late Neolithic flints have been found at this site. Excavated 1973 Unpublished: see Grimes 1984 PEN-Y-BONT, OGMORE (SS863756) Pottery, hearth and flints Hamilton and Aldhouse-Green 1998; 1999; Gibson 1998 MOUNT PLEASANT, NEWTON NOTTAGE (SS83387985) Hut, hearth, pottery Savory 1952; RCAHMW 1976a CEFN CILSANWS HUT SITE (SO02480995) Hut consisting of 46 stake holes found under cairn. The hut contained fragments of Mortlake style Peterborough Ware and flint flakes Webley 1958; RCAHMW 1997 CEFN BRYN 10 (GREAT CARN) SAM Gml96 (SS49029055) Trench, pit, posthole and hearth associated with Peterborough ware and worked flint; found under cairn. Ward 1987 Funerary and ritual CEFN BRYN BURIAL CHAMBER (NICHOLASTON) SAM Gml67 (SS50758881) Partly excavated chambered tomb, with an orthostatic chamber surviving in a roughly central position in what remains of a long mound. The mound was made up peaty soil and stone fragments, and no trace of an entrance passage was found. The chamber had been robbed at some time before the excavation. Williams 1940, 178-81 CEFN DRUM CHAMBERED TOMB (SN61360453,) Discovered during the course of the excavation of a deserted medieval settlement on Cefn Drum. A pear-shaped chamber of coursed rubble construction, with an attached orthostatic passage ending in a pit in the mouth of a hornwork and containing cremated bone and charcoal, were identified within the remains of a mound with some stone kerbing. -

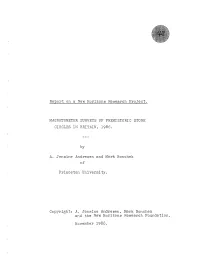

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER SURVEYS OF PREHISTORIC STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, 1986. by A. Jensine Andresen and Mark Bonchek of Princeton University. Copyright: A. Jensine Andresen, Mark Bonchek and the New Horizons Research Foundation. November 1986. CONTENTS. Introductory Note. Magnetic Surveying Project Report on Geomantic Resea England, June 16 - July 22, 1986. Selected Notes. Bibliography. 1. Introductory Note. This report deals with a piece of research falling within the group of enquiries comprised under the term "geomancy". which has come into use during the past twenty years or so to connote what could perhaps be called the as yet somewhat speculative study of various presumed subtle or occult properties of terrestrial landscapes and the earth beneath them. In earlier times the word "geomancy" was used rather differently in relation to divination or prophecy carried out by means of some aspect of the earth, but nowadays it refers to the study of what might be loosely called "earth mysteries". These include the ancient Chinese lore and practical art of Fengshui -- the correct placing of buildings with respect to the local conformation of hills and dales, the orientation of medieval churches, the setting of buildings and monuments along straight lines (i.e. the so-called ley lines or leys). These topics all aroused interest in the early decades of the present century. Similarly,since about 1900 interest in megalithic monuments throughout western Europe has steadily increased. This can be traced to a variety of causes, which include increased study and popularisation of anthropology, folklore and primitive religion (e.g. -

Rude Stone Monuments Chapt

RUDE STONE MONUMENTS IN ALL COUNTRIES; THEIR AGE AND USES. BY JAMES FERGUSSON, D. C. L., F. R. S, V.P.R.A.S., F.R.I.B.A., &c, WITH TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY-FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS. LONDON: ,JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. 1872. The right of Translation is reserved. PREFACE WHEN, in the year 1854, I was arranging the scheme for the ‘Handbook of Architecture,’ one chapter of about fifty pages was allotted to the Rude Stone Monuments then known. When, however, I came seriously to consult the authorities I had marked out, and to arrange my ideas preparatory to writing it, I found the whole subject in such a state of confusion and uncertainty as to be wholly unsuited for introduction into a work, the main object of which was to give a clear but succinct account of what was known and admitted with regard to the architectural styles of the world. Again, ten years afterwards, while engaged in re-writing this ‘Handbook’ as a History of Architecture,’ the same difficulties presented themselves. It is true that in the interval the Druids, with their Dracontia, had lost much of the hold they possessed on the mind of the public; but, to a great extent, they had been replaced by prehistoric myths, which, though free from their absurdity, were hardly less perplexing. The consequence was that then, as in the first instance, it would have been necessary to argue every point and defend every position. Nothing could be taken for granted, and no narrative was possible, the matter was, therefore, a second time allowed quietly to drop without being noticed. -

WRAP THESIS Shilliam 1986.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/34806 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. FOREIGN INFLUENCES ON AND INNOVATION IN ENGLISH TOMB SCULPTURE IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Nicola Jane Shilliam B.A. (Warwick) Ph.D. dissertation Warwick University History of Art September 1986 SUMMARY This study is an investigation of stylistic and iconographic innovation in English tomb sculpture from the accession of King Henry VIII through the first half of the sixteenth century, a period during which Tudor society and Tudor art were in transition as a result of greater interaction with continental Europe. The form of the tomb was moulded by contemporary cultural, temporal and spiritual innovations, as well as by the force of artistic personalities and the directives of patrons. Conversely, tomb sculpture is an inherently conservative art, and old traditions and practices were resistant to innovation. The early chapters examine different means of change as illustrated by a particular group of tombs. The most direct innovations were introduced by the royal tombs by Pietro Torrigiano in Westminster Abbey. The function of Italian merchants in England as intermediaries between Italian artists and English patrons is considered. Italian artists also introduced terracotta to England. -

Stone-Cist Grave at Kaseküla, Western Estonia, in the Light of Ams Dates of the Human Bones

Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 2012, 16, 2, 91–117 doi: 10.3176/arch.2012.2.01 Margot Laneman STONE-CIST GRAVE AT KASEKÜLA, WESTERN ESTONIA, IN THE LIGHT OF AMS DATES OF THE HUMAN BONES The article discusses new AMS dates of the human bones at stone-cist grave I at Kaseküla, western Estonia, in the context of previously existent radiocarbon dates, artefact finds and osteological studies. There are altogether 12 radiocarbon dates for 10 inhumations (i.e. roughly a third of all burials) of the grave, provided by two laboratories. The dates suggest three temporally separated periods in the use life of the grave(s): the Late Bronze Age, the Pre-Roman Iron Age and the Late Iron Age. In the latter period, the grave was probably reserved for infant burials only. Along with chronological issues, the article discusses the apparently unusual structure of the grave and compares two competing osteological studies of the grave’s bone assemblage from an archaeologist’s point of view. Margot Laneman, Institute of History and Archaeology, University of Tartu, 18 Ülikooli St., 50090 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] Introduction The main aim of this article is to present and discuss new radiocarbon (AMS) dates of the human bones collected from stone-cist grave I at Kaseküla, western Estonia. The stone-cist grave was excavated by Mati Mandel in 1973 with the purpose of specifying the settlement history of the region (Mandel 1975). So far it has remained the only excavated stone-cist grave in mainland western Estonia (Mandel 2003, fig. 20). Excavation also uncovered a Late Neolithic settlement site beneath the grave, which was further investigated by Aivar Kriiska in 1997 (Kriiska et al. -

Commission C4 Annual Report 2017

Commission C4 annual report 2017 Report for the period January to December 2017 The Commission's main achievements during 2017 are as follows. 1 The publication of the second ICOMOS-IAU Thematic Study on astronomical heritage ("TS2"). Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the Context of the World Heritage Convention: Thematic Study no. 2 was published as an e-book in June, in time for the 2017 UNESCO World Heritage Committee meeting in Kraków, and as a paperback in November, in time for the ICOMOS General Assembly in Delhi. ICOMOS Thematic Studies (sometimes produced in co-operation with specialist partner organisations) aim to provide a synthesis of current research and knowledge on a specific theme and/or region, and are useful to State Parties wishing to nominate a heritage property for inscription on the World Heritage List. TS2 examines a number of key questions relating to astronomical heritage sites and their potential recognition as World Heritage, attempting to identify what might constitute “outstanding universal value” (OUV) in relation to astronomy. It represents the culmination of several years' work to address some of the most challenging issues raised in the first ICOMOS-IAU Thematic Study ("TS1"), published in 2010. A particularly complex issue is the recognition and protection of dark skies. Dark sky areas cannot in themselves be considered as potential World Heritage Sites, but TS2 includes a thematic chapter by Michel Cotte of ICOMOS considering a range of ways in which dark sky values can be interrelated with broader cultural or natural values of a place and thereby contribute to its overall cultural or natural value and potential OUV.