UC Santa Barbara Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Infonnation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 KLÀNNISHNESS AND THE KU KLUX KLAN: THE RHETORIC AND ETHICS OF GENRE THEORY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Robert McGee, B.S., M.S. -

Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park 4011 Grant Drive Earlimart, CA 93219 (661) 849-3433

Our Mission The mission of California State Parks is Colonel to provide for the health, inspiration and education of the people of California by helping n 1908 a group of to preserve the state’s extraordinary biological I Allensworth diversity, protecting its most valued natural and African Americans cultural resources, and creating opportunities State Historic Park for high-quality outdoor recreation. led by Colonel Allen Allensworth founded a town that would combine pride of ownership, California State Parks supports equal access. Prior to arrival, visitors with disabilities who equality of opportunity, need assistance should contact the park at (661) 849-3433. If you need this publication in an and high ideals. alternate format, contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA STATE PARKS P.O. Box 942896 Sacramento, CA 94296-0001 For information call: (800) 777-0369 (916) 653-6995, outside the U.S. 711, TTY relay service www.parks.ca.gov Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park 4011 Grant Drive Earlimart, CA 93219 (661) 849-3433 © 2007 California State Parks (Rev. 2017) I n the southern San Joaquin Valley, music teacher, and the colony of Allensworth a modest but growing assemblage of gifted musician, began to rise from the flat restored and reconstructed buildings marks and they raised two countryside — California’s the location of Colonel Allensworth State daughters. In 1886, first town founded, financed, Historic Park. A schoolhouse, a Baptist church, with a doctorate of and governed by businesses, homes, a hotel, a library, and theology, Allensworth African Americans. various other structures symbolize the rebirth became chaplain to The name and reputation of one man’s dream of an independent, the 24th Infantry, one of Colonel Allensworth democratic town where African Americans of the Army’s four inspired African Americans could live in control of their own destiny. -

Annotated Bibliography -- Trailtones

Annotated Bibliography -- Trailtones Part Three: Annotated Bibliography Contents: Abdul, Raoul. Blacks in Classical Music. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1977. [Mentions Tucson-born Ulysses Kay and his 'New Horizons' composition, performed by the Moscow State Radio Orchestra and cited in Pravda in 1958. His most recent opera was Margeret Walker's Jubilee.] Adams, Alice D. The Neglected Period of Anti-Slavery n America 1808-1831. Gloucester, Massachusetts: Peter Smith, 1964. [Charts the locations of Colonization groups in America.] Adams, George W. Doctors in Blue: the Medical History of the Union Army. New York: Henry Schuman, 1952. [Gives general information about the Civil War doctors.] Agee, Victoria. National Inventory of Documentary Sources in the United States. Teanack, New Jersey: Chadwick Healy, 1983. [The Black History collection is cited . Also found are: Mexico City Census counts, Arizona Indians, the Army, Fourth Colored Infantry, New Mexico and Civil War Pension information.] Ainsworth, Fred C. The War of the Rebellion Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. General Index. [Volumes I and Volume IV deal with Arizona.] Alwick, Henry. A Geography of Commodities. London: George G. Harrop and Co., 1962. [Tells about distribution of workers with certain crops, like sugar cane.] Amann, William F.,ed. Personnel of the Civil War: The Union Armies. New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1961. [Gives Civil War genealogy of the Black Regiments that moved into Arizona from the United States Colored troops.] American Folklife Center. Ethnic Recordings in America: a Neglected Heritage. Washington: Library of Congress, 1982. [Talks of the Black Sacred Harping Singing, Blues & Gospel and Blues records of 1943- 66 by Mike Leadbetter.] American Historical Association Annual Report. -

Soul City Records Discography

Soul City Records Discography 91000 series SCM 91000/SCS 92000 - Up, Up And Away - The 5TH DIMENSION [1967] Up-Up And Away/Another Day, Another Heartache/Which Way To Nowhere/California My Way/Misty Roses//Go Where You Wanna Go/Never Gonna Be The Same/Pattern People/Rosecrans Boulevard/Learn How To Fly/Poor Side Of Town SCM 91001/SCS 92001 - The Magic Garden - The 5TH DIMENSION [1968] (reissued as The Worst That Could Happen) Prologue/The Magic Garden/Summer’s Daughter/Dreams-Pax-Nepenthe/Carpet Man/Ticket To Tide//Requiem: 820 Latham/The Girls’ Song/The Worst That Could Happen/Orange Air/Paper Cup/Epilogue SCS 92002 - Stoned Soul Picnic - The 5TH DIMENSION [1968] Sweet Blindness/I’ll Never Be The Same Again/The Sailboat Song/It’s A Great Life/Stoned Soul Picnic//California Soul/Lovin’ Stew/Broken Wing Bird/Good News/Bobbie’s Blues (Who Do You Think Of?)/The Eleventh Song (What A Groovy Day!) SCS 92003 - The Songs Of James Hendricks - JAMES HENDRICKS [1968] Big Wheels/City Ways/Colorado Rocky Mountains/Good Goodbye/I Think Of You/Lily Of The Valley/Look To Your Soul/Shady Green Pastures/Summer Rain/Sunshine Showers/You Don’t Know My Mind [*] SCS 92005 - The Age Of Aquarius - The 5TH DIMENSION [1969] Medley: Aquarius-Let The Sunshine In (The Flesh Failures)/Blowing Away/Skinny Man/Wedding Bell Blues/Don’ Tcha Hear Me Callin’ To Ya/The Hideaway//Workin’ On A Groovy Thing/Let It Be Me/Sunshine Of Your Love/The Winds Of Heaven/Those Were The Days/Let The Sunshine In (Reprise) SCS 92006 - Searching For The Dolphins - AL WILSON [1969] The Dolphins/By -

Index President's Corner

Fall 2009 Alasdair Brooks, DPhil, Newsletter Editor, School of Archaeology and Ancient History, University of Leicester, United Kingdom Index President’s Corner President’s Corner .......................................1 Lu Ann De Cunzo Images of the Past .........................................3 SHA Committee News ...............................4 The minutes of the June SHA Board meeting Constitution and Bylaws Changes: These Mission Statement & Strategic Priorities 4 will be published in the next newsletter; core documents were last amended APT Student Subcommittee ..................4 my column in this issue of the Newsletter in 2003, at which time the Secretary- 2010 Conference Preliminary Program .....6 presents some of the highlights. Treasurer was split into two positions, 2010 Conference Registration Form .......20 and a 2-year presidency established. A 2010 Corporate Sponsor Form ................23 Strategic Plan: change to the Mission Statement, Article 2010 Silent Auction Donations ...............25 I am most pleased to report that the Board II of the SHA Constitution, requires 2010 Student Volunteer Form .................26 approved a revised Mission Statement and membership approval. Other changes may Current Research ........................................27 a Strategic Workplan of long-term (5-year), be in order to align with strategic planning Africa ........................................................28 mid-term (2-year), and short-term (1-year) directions, electronic means of membership Australasia and Antarctica -

The Heart of an Industry: the Role of the Bracero Program in the Growth of Viticulture in Sonoma and Napa Counties

THE HEART OF AN INDUSTRY: THE ROLE OF THE BRACERO PROGRAM IN THE GROWTH OF VITICULTURE IN SONOMA AND NAPA COUNTIES by Zachary A. Lawrence A thesis submitted to Sonoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Copyright 2005 By Zachary A. Lawrence ii AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS I grant permission for the reproduction of parts of this thesis without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provide proper acknowledgement of authorship. Permission to reproduce this thesis in its entirety must be obtained from me. iii THE HEART OF AN INDUSTRY: THE ROLE OF THE BRACERO PROGRAM IN THE GROWTH OF VITICULTURE IN SONOMA AND NAPA COUNTIES Thesis by Zachary A. Lawrence ABSTRACT This study examines the role of the Bracero Program in the growth of Sonoma and Napa County viticulture in an attempt to understand how important bracero labor was to the industry. While most histories of the Bracero Program are nationwide or statewide in scope, this study explores the regional complexities of how and why the program was used in Sonoma and Napa Counties, how both the growers and laborers in the region felt about it, and how this was different from and similar to other regions. Government documents provided the statistics necessary to determine the demographic changes in the region due to the Bracero Program. Important primary source material that provided the human side of the story includes a number of oral history interviews I conducted, the collection of Wine Industry Oral Histories, and various regional newspaper articles. -

Program Book

W Congratu lations to m Harry Turtledove WindyCon Guest of Honor HARRY I I if 11T1! \ / Fr6m the i/S/3 RW. ; Ny frJ' 11 UU bestselling author of TURTLEDOVE I Xi RR I THE SONS Of THE SOUTH Turtledove curious A of > | p^ ^p« | M| B | JR : : Rallied All I I II I Al |m ' Curious Notions In High Places 0-765-34610-9 • S6.95ZS9.99 Can. 0-765-30696-4 • S22.95/S30.95 Can. In paperback December 2005 In hardcover January 2006 In a parallel-world twenty-first century Harry Turtledove brings us to the twenty- San Francisco, Paul Goines and his father first century Kingdom ofVersailles, where must obtain raw materials for our timeline slavery is still common. Annette Klein while guarding the secret of Crosstime belongs to a family of Crosstime Traffic Traffic. When they fall under suspicion, agents, and she frequently travels between Paul and his father must make up a lie that two worlds. When Annette’s train is attacked puts Crosstime Traffic at risk. and she is separated from her parents, she wakes to find herself held captive in a caravan “Entertaining,. .Turtledove sets up of slaves and Crosstime Traffic may never a believable alternate reality with recover her. impeccable research, compelling characters and plausible details.” “One of alternate history’s authentic —Romantic Times BookClub Magazine, modern masters.” —Booklist three-star review rwr www.roi.com Adventures in Alternate History 'w&ritlh. our Esteemed Guests of Honor Harry Turtledove Bill Holbrook Gil G^x»sup<1 Erin Gray Jim Rittenhouse Mate s&nd Eouie jBuclklin Mark Osier Esther JFriesner grrad si xM.'OLl'ti't'o.de of additional guests ijrud'o.dlxxg Alex and JPliyllis Eisenstein Eric IF lint Poland Green axidL Erieda Murray- Jody Lynn J^ye and IBill Fawcett Frederik E»olil and ESlizzsJbetlx Anne Hull Tom Smith Gene Wolfe November 11» 13, 2005 Ono Weekend Only! Capricon 26 -Putting the UNIVERSE into UNIVERSITY Now accepting applications for Spring 2006 (Feb. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

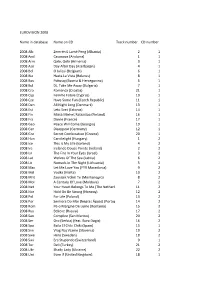

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

Building Communities – Economics & Ethnicity

Building Communities – Economics & Ethnicity Jennifer Helzer, California State University, Stanislaus Helzer, 1 Delta Protection Commission Delta Narratives (Revision Final) June 11, 2015 Building Communities – Economics & Ethnicity Jennifer Helzer, California State University, Stanislaus INTRODUCTION Approaching the Delta from the east, off of Interstate 5, the hurried and harried pace of life gives way to a gradual western sloping landscape of manicured fields. As the morning fog burns away, glimpses of old barns, field equipment, and neatly stacked fruit crates appear alongside the road. As one approaches town, heavy‐duty pick‐up trucks meet at the four‐way stop with their driver motioning for visitors to take the right‐of‐way. The post office and local coffee shop buzz with morning routines. A tour through the Delta carries visitors along levee roads, across iconic bridges and into culturally rich historic towns. Orchards and row crops expand from levee roads; and farmsteads and stately homes exist alongside ethnic heritage landscapes and new commercial developments. The communities of the Delta are places of the present and the past that are stitched together by a network of railroads, canals and levees, and by the open spaces that link them together. These are the first impressions of the Delta as a place and the start of many questions. What is the meaning of this place, who made this place and how has it changed through time? In the 1850s, powerful economic, political and social forces precipitated momentous change in the Delta region of California: 1) the California Gold Rush, 2) levee construction and agricultural development, and 3) the migration and settlement of domestic, European and Asian cultural groups. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don Mclean 1972 4

AS VOTED AT OLDIESBOARD.COM 10/30/17 THROUGH 12/4/17 CONGRATULATIONS TO “HEY JUDE”, THE #1 SELECTION FOR THE 19 TH TIME IN 20 YEARS! Ti tle Artist Year 1 Hey Jude Beatles 1968 2 (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don McLean 1972 4 Light My Fire Doors 1967 5 In The Still Of The Nite Five Satins 1956 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand Beatles 1964 7 MacArthur Park Richard Harris 1968 8 Rag Doll Four Seasons 1964 9 God Only Knows Beach Boys 1966 10 Ain't No Mount ain High Enough Diana Ross 1970 11 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon and Garfunkel 1970 12 Because Dave Clark Five 1964 13 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 14 Cherish Association 1966 15 She Loves You Beatles 1964 16 Hotel California Eagles 1977 17 St airway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 18 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 19 My Girl Temptations 1965 20 Let It Be Beatles 1970 21 Be My Baby Ronettes 1963 22 Downtown Petula Clark 1965 23 Since I Don't Have You Skyliners 1959 24 To Sir With Love Lul u 1967 25 Brandy (You're A Fine Girl) Looking Glass 1972 26 Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley 1969 27 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' Righteous Brothers 1965 28 You Really Got Me Kinks 19 64 29 Wichita Lineman Glen Campbell 1968 30 The Rain The Park & Ot her Things Cowsills 1967 31 A Hard Day's Night Beatles 1964 32 A Day In The Life Beatles 1967 33 Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 34 Imagine John Lennon 1971 35 I Only Have Eyes For You Flamingos 1959 36 Waterloo Sunset Kinks 1967 37 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 76 -92 38 Sugar Sugar Archies 1969 39 What's