Translating the Codex Mendoza Daniela Bleichmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pocahontas's Two Rescues and Her Fluid Loyalty

言語・地域文化研究 第 ₂6 号 2020 103 Pocahontas’s Two Rescues and Her Fluid Loyalty Hiroyuki Tsukada ポカホンタスの二つの助命と忠誠心の揺らぎ 塚田 浩幸 要 旨 ポカホンタスは、二度、ジョン・スミスの命を救った。一度目は有名な助命で、1607 年 12 月、インディアンの首長パウハタンによる処刑の寸前に、ポカホンタスが捕虜スミ スに自分の体をなげうって助命をした。これは、スミスの死と生まれ変わりを象徴的に 意味し、入植者をインディアンの世界に迎え入れる儀式で、ポカホンタスはスミスを救 うというあらかじめ決められた役割を担った。この一度目の助命の真偽については長ら く論争が行なわれてきたが、スミスが 1608 年 6 月の報告書簡でポカホンタスを「比類な き人物」と高く評価できたという事実は、助命が実際に起きたことを示している。その 6 月の時点で、スミスは助命の他に、取引や物資の提供と人質解放交渉の場面でポカホ ンタスと会う機会を持っていたが、それらの場面においては、スミスが「比類なき人物」 と評価することができるほどの行動をポカホンタスがとっていなかったからである。そ して、スミスがその報告書簡でポカホンタスを紹介したのは、入植事業の宣伝のために インディアンとの平和友好をアピールするねらいがあった。つまり、スミスに批判的な 研究者が主張するように、スミスがポカホンタスの人気にあやかって自分の名声をあげ るために助命を捏造したのではなく、助命に感銘を受けたスミスがポカホンタスの人気 を作り上げたといえるのである。 パウハタンは、一度目の助命でポカホンタスをインディアンと入植者の平和友好のシ ンボルとして仕立て上げ、その後の平和的な外交の場面にもポカホンタスを同行させて いた。しかしながら、二度目の助命は、パウハタンの外交方針に逆らって、ポカホンタ ス自身の意思によって行なわれた。1609 年 1 月、インディアンと入植者の関係が悪化す るなか、パウハタンがスミスを本当に襲おうとしているところをポカホンタスがスミス に密告して救った。この二つの助命のあいだの期間、ポカホンタスは入植者と頻繁に会 うなかで理解を深め、パウハタン連合のインディアンとしての忠誠心に揺らぎを生じさ せていたのである。つまり、ポカホンタスは、単なるパウハタンの遣いとしての平和友 好のシンボルであることをやめ、自らを平和友好の使者として確立させるに至ったので ある。 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示 4.0 国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja 104 論文 ポカホンタスの二つの助命と忠誠心の揺らぎ (塚田 浩幸) Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. A special relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith 3. Refutation of all existing theories 4. Demonstration of the veracity of the rescue 5. Conclusion 1. Introduction Pocahontas saved John Smith twice. The frst instance came in December 1607, when she symbolically ofered her own head to save Smith’s -

4.0 a Guide to Warrior Suits 4.1 the Basic Feather Costume

4.0 A GUIDE TO WARRIOR SUITS Here follows a broad outline of the various warrior suits that were known to be associated with the Aztecs. It should be noted that all of these showy feather suits were available to the noblemen only, and could never be worn by the common man. The prime source of information for the following chapter is from the tribute lists in the Codex Mendoza and the Matricula de Tributos, the suit and banner lists in the Primeros Memoriales plus some commentary in Duran's Book of the Gods, History of the Indies and some of the Florentine Codex. The first two give clear examples of many different types of war suits, as well as a defined list of warrior and priest suits with their associated rank. Unfortunately they do not show all the suit types possible, nor do they explain what several of the suit types sent in tribute were for. Trying to mesh these sources is not neat, and some interpretation is required. While Chapter 3 examined the tribute from various provinces on a province by province basis, this chapter concentrates only on the warrior suit types as individual topics. The Mendoza Noble Warrior List (Section 4.2) and Priest Warrior List (Section 4.3) are further expanded upon with information from the tribute lists and then any other primary sources with relevant information or images. These lists are then followed up by a list of suit types not covered by either of these two lists (Section 4.4.) This section of the documentation does not cover the organisational or ranking levels of the suits except as a method for listing the suits for discussion. -

T 1/24 = Unit 3 Timeline • C 21 Q/V/A Due W 1/25 • AP TEST

Reminders: Period 4 Key Concepts: • DUE: T 1/24 = Unit 3 Timeline Pick an APWH Region • C 21 Q/V/A due W 1/25 Find ONE Change Find ONE Continuity • AP TEST REGISTRATION = 2/1-2/13 ONLY 15th Century MOVIE NOTES?? Unit 3: SAQs……. Roots VS Routes? Byzantine Empire/Western Europe Islam MUST know correct location of the historical developments that you are discussing! 1. a) Identify and explain one economic impact Islamic traders had on sub-Saharan Africa. b) Identify and explain one cultural influence Islamic traders had on sub-Saharan Africa. c) Identify and explain one example of where local sub-Saharan cultures resisted assimilation with Islam. a) Specific examples! : salt, gold, slaves, horses, spices, domestication of camels, camel saddles cultural diffusion of Islam (Mansa Musa was NOT an Islamic trader) : THEN explain how the above specifically influenced the economy of sub-Saharan Africa b) Specific examples!: cultural diffusion of Islam = Five Pillars of Faith practiced, use of the Quran, 5 prayers a day, inspired to go on the hajj Conversion of merchants to Islam THEN WHY? Did Islamic traders influence culture in that way? c) Resistance to Islam: Axum, not wearing the veil, Bantu (WHY is that an example of resistance to Islam?) 2. a) Identify and explain one reason for the change in Byzantine territory between 565 CE and 1025 CE b) Identify an explain one way that geography/interaction with the environment influenced the economic development of the Byzantine Empire c) Identify and explain one way that geography/interaction with the environment influenced the economic development of Western Europe between 600-1450 CE. -

Rethinking the Conquest : an Exploration of the Similarities Between Pre-Contact Spanish and Mexica Society, Culture, and Royalty

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2015 Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2015 Samantha Billing Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Billing, Samantha, "Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty" (2015). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 155. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/155 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by SAMANTHA BILLING 2015 All Rights Reserved RETHINKING THE CONQUEST: AN EXPLORATION OF THE SIMILARITIES BETWEEN PRE‐CONTACT SPANISH AND MEXICA SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND ROYALTY An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa May 2015 ABSTRACT The Spanish Conquest has been historically marked by the year 1521 and is popularly thought of as an absolute and complete process of indigenous subjugation in the New World. Alongside this idea comes the widespread narrative that describes a barbaric, uncivilized group of indigenous people being conquered and subjugated by a more sophisticated and superior group of Europeans. -

The Cult of the Book. What Precolumbian Writing Contributes to Philology

10.3726/78000_29 The Cult of the Book. What Precolumbian Writing Contributes to Philology Markus Eberl Vanderbilt University, Nashville Abstract Precolumbian people developed writing independently from the Old World. In Mesoamerica, writing existed among the Olmecs, the Zapotecs, the Maya, the Mixtecs, the Aztecs, on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and at Teotihuacan. In South America, the knotted strings or khipus were used. Since their decipherment is still ongoing, Precolumbian writing systems have often been studied only from an epigraphic perspective and in isolation. I argue that they hold considerable interest for philology because they complement the latter’s focus on Western writing. I outline the eight best-known Precolumbian writing systems and de- scribe their diversity in form, style, and content. These writing systems conceptualize writing and written communication in different ways and contribute new perspectives to the study of ancient texts and languages. Keywords Precolumbian writing, decipherment, defining writing, authoritative discourses, canon Introduction Written historical sources form the basis for philology. Traditionally these come from the Western world, especially ancient Greece and Rome. Few classically trained scholars are aware of the ancient writing systems in the Americas and the recent advances in deciphering them. In Mesoamerica – the area of south-central Mexico and western Central America – various societies had writing (Figure 1). This included the Olmecs, the Zapotecs, the people of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, the Maya, Teotihuacan, Mix- tecs, and the Aztecs. In South America, the Inka used knotted strings or khipus (Figure 2). At least eight writing systems are attested. They differ in language, formal structure, and content. -

Brennan ARC to Travel Writing 22 Aug

This is a repository copy of Editorial Matters. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/120551/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Brennan, MG orcid.org/0000-0001-6310-9722 (2019) Editorial Matters. In: Pettinger, A and Youngs, T, (eds.) The Routledge Research Companion to Travel Writing. Routledge , Abingdon, UK . ISBN 9781472417923 https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315613710 © 2019 selection and editorial matter, Alasdair Pettinger and Tim Youngs; individual chapters, the contributors. This is an author produced version of a book chapter published in The Routledge Research Companion to Travel Writing. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 22 August 2017 Michael G. Brennan, ‘Editorial Matters’, for The Ashgate Research Companion to Travel Writing, ed. Tim Youngs and Alasdair Pettinger, Routledge (forthcoming) Michael G. Brennan is Professor of Renaissance Studies at the School of English, University of Leeds. -

Crafting Knowledge of the Mughal Empire In

Essays in History Volume 52 (2019) Crafting Knowledge of the Mughal Empire in Samuel Purchas’s Hakluytus Posthumus and Seventeenth- Century English Travel Accounts Madeline Grimm University of California Los Angeles Introduction In October 1614, the East India Company nominated Sir Thomas Roe to serve as the first -En glish ambassador to the Mughal Empire. George Abbot, the Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote to Roe in January 1617, while Roe resided at Emperor Jahangir’s court. Abbot advised him to closely observe events in India, for “as things now stand throughout the whole worlde, there is no place so remote, but that the consideration thereof is mediately or immediately of conse- quence to our affaires here.”1 Abbot assured Roe that his post in India, far from London and royal favor, was essential to England’s national interests. He encouraged Roe to report to him on Jahangir’s habits and demeanor, the activities of Dutch and French merchants, and any poten- tially valuable merchandise. In doing so, he articulated the need to obtain information about India that was reliable and could be used to England’s advantage against their European rivals. The English needed to think globally if they were to acquire significant political and economic power in Europe. Roe’s response to Abbot and his other writings from the embassy circulated in several forms. While in India, he had kept a journal where he noted the significant events at court each day. The journal and copies of Roe’s letters were assembled into one manuscript.2 Roe had this work in his possession when he left India and copies of it were sent to the East India Company (EIC) at their offices in London. -

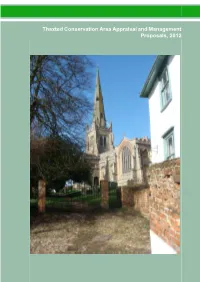

Thaxted Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2012 Thaxted Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2012

Thaxted Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2012 Thaxted Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals, 2012 Contents 1 Part 1: Appraisal 4 Introduction 4 Planning Legislative Framework 6 Planning Policy Framework 7 The General Character of Thaxted 8 Origins and Historic Development 14 Character Analysis 18 Area 1 - The west of the town including Bolford Street, Newbiggen Street, Watling Street, Watling Lane, Vicarage Lane, Margaret Street, Bell Lane, Stoney Lane, Fishmarket Street and Town Street 20 Area 2 - The east and south of the town including Park Street, Mill End, Orange Street and Dunmow Road 36 Overall Summary 43 1 Part 2 - Management Proposals 45 Revised Conservation Area Boundary 45 General Planning Controls and Good Practice in the Conservation Area 45 Planning Controls and Good Practice in Respect of the Potential Need to Undertake an Archeological Field 46 Planning Control and Good Practice, Listed Buildings 46 Planning Controls and Good Practice in Respect of Other Buildings that Make an Important Architectural or Historic Contribution 46 Planning Controls and Good Practice in Respect of Other Distinctive Features that Make an Important Architectural or Historic Contribution 47 Planning Control and Good Practice, Important Open Spaces, Trees and Groups of Trees 47 Proposed Controls in Respect of Other Distinctive Features that make an Important Visual or Historic Contribution 47 Enhancement Proposals to Deal with Detracting Elements 48 1 Maps 51 Fig 1 - 1877 Ordnance Survey Map 51 Fig 2 - Character -

NYUPRESS Relation of Virginia

Relation of Virginia A Boy’s Memoir of Life with the Powhatans and the Patawomecks BY HENRY SPELMAN EDITED BY KAREN ORDAHL KUPPERMAN Instructor’s Guide “Being in displeasure of my friends, and desirous to see other countries, after three months sail we come with prosperous winds in sight of Virginia.” So begins the fascinating tale of Henry Spelman, a 14 year- old boy whose mother sent him to Virginia in 1609. One of Jamestown’s early arrivals, Spelman soon became an integral player, and sometimes a pawn, in the power struggle between the Chesapeake Algonquians and the English settlers. Shortly after he arrived in the Chesapeake, Henry accompanied another English boy, Thomas Savage, to Powhatan’s capital and after a few months accompanied the Patawomeck chief Iopassus to the Potomac. Spelman learned Chesapeake Algonquian languages and customs, acted as an interpreter, and knew a host of colonial America’s most well-known figures, from Pocahontas to Powhatan to Captain John Smith. This remarkable manuscript tells Henry’s story in his own words, and it is the only description of Chesapeake Algonquian culture written with an insider’s knowledge. Spelman’s account is lively and violent, rich with anthropological and historical detail. 96 pages | Cloth | 978-1-4798-3519-5 Memoir | Colonial History A valuable and unique primary document, this book illuminates the beginnings of English America and tells us much about how the Chesapeake Algonquians viewed the English invaders. It provides the first transcription from the original manuscript since 1872. www.nyupress.org NYU PRESS Instructor’s Guide — 3 Discussion Questions — 6 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE 3 BOOK BREAKDOWN Henry Spelman was fourteen years old when he arrived in England’s recently-founded Jamestown colony in 1609. -

Eclipses in the Aztec Codices Event Was Actually Perceived

IN ORIGINAL FORM PUBLISHED IN: arXiv: 0000.00000 [physics.hist-ph] Habilitation at the University of Heidelberg Date: 20th August 2020 Eclipses in the Aztec Codices Emil Khalisi D–69126 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: ekhalisi[at]khalisi[dot]com Abstract. This paper centers on the collection of accounts on solar eclipses from the era of the Aztecs in Mesoamerica, about 1300 to 1550 AD. We present a list of all eclipse events complying with the topological visibility from the capital Tenochtitlan. Forty records of 23 eclipses entered the various Aztec manuscripts (codices), usually those of large magnitude. Each event is discussed with regard to its historical context, as we try to comprehend the importance the Aztecs gave to the phenomenon. It seems that this culture paid noticeably less attention to eclipses than the civilisations in the “Old World”. People did not understand the cause of it and did not care as much about astronomy as in Babylonia and ancient China. Furthermore, we discuss the legend on the comet of Moctezuma II. It turns out that the post-conquest writers misconceived what the sighting was meant to be. Keywords: Solar eclipse, Aztec, Mesoamerica, Astronomical dating, Moctezuma’s Comet. 1 Introduction necessity, because the belief was interlocked with some re- peating phenomena, for instance, the end of the calendrical The Mesoamerican peoples developed their culture inde- cycle, rebirth of the sun, or re-appearances of the planet pendent from the civilisations in the Euro-Asian domain. Venus. Among the tribes on both American continents only the Most reliable information about natural phenomena Maya achieved an advanced level of worldwide recognition. -

Hand Spinning and Cotton in the Aztec Empire, As Revealed by the Codex Mendoza

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2002 Hand Spinning and Cotton in the Aztec Empire, as Revealed by the Codex Mendoza Susan M. Strawn Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Strawn, Susan M., "Hand Spinning and Cotton in the Aztec Empire, as Revealed by the Codex Mendoza" (2002). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 420. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/420 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hand Spinning and Cotton in the Aztec Empire, as Revealed by the Codex Mendoza Susan M. Strawn At a lecture titled “Growing Up Aztec,” art historian Jill Furst illustrated Aztec childhood with images from the Codex Mendoza, an extraordinary, post- Hispanic pictorial manuscript from central Mexico. The Mendoza specified the lessons, punishments, and even the number of tortillas appropriate for boys and girls during each year of childhood. Interestingly, the Codex Mendoza showed spinning as the only instruction given to Aztec girls between the ages of four and thirteen years. In 1992, the University of California Press published a full color facsimile of the Codex Mendoza1 with a translation into English and with extensive interpretation in four volumes edited by Frances F. Berdan and Patricia Rieff Anawalt. -

Velasco Map”: a Case of Forgery? Persistent URL for Citation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought toPage you by 1CORE provided by Texas A&M University Coordinates Series A, No. 5 The So-Called “Velasco Map”: A Case of Forgery? Persistent URL for citation: http://purl.oclc.org/coordinates/a5.pdf David Y. Allen Date of Publication: 02/14/06 David Y. Allen (e-mail: [email protected]) is Map Revised: Librarian, emeritus, at Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York. Abstract This article examines a well-known map of the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada allegedly made in or around 1610. The map was uncovered in the Spanish Archives at Simancas in 1887. Supposedly, it is a copy of an anonymous English map, which was sent to King Phillip III of Spain by the Spanish ambassador to London, Don Alonzo de Velasco. This article raises the possibility that the map may actually be a nineteenth- century forgery. The map is based primarily on information found on early seventeenth-century maps, most of which were not published in 1610, although it is possible that manuscript copies of these maps might have been available as early as 1610. The overall geographic framework of the map seems to be improbably accurate for its supposed date of creation. The map contains numerous oddities, and many features on the map do not appear on other maps made in the early seventeenth century. Overall it seems anachronistic and it stands in isolation from other maps made around 1600. Although no single feature on the map proves beyond a doubt that it is a forgery, the overall weight of the evidence makes it seem highly probable that it is a fake.