The Case of Visby Cathedral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sailing Ancient Trade Routes Helsinki to Copenhagen Aboard Sea Cloud II June 27–July 9, 2020 Dear Royal Oak Members and Friends

Sailing Ancient Trade Routes Helsinki to Copenhagen Aboard Sea Cloud II June 27–July 9, 2020 Dear Royal Oak Members and Friends, Next summer, enjoy a Baltic adventure aboard the luxury barque Sea Cloud II during the region’s loveliest season, when the northern sunlight shines on stunning medieval cities and shimmers on the sea well into the night. On this cruise, retrace the trade routes of the Hanseatic League, an alliance of northern European merchant towns that dominated Baltic commerce from the 13th through the 15th centuries. Admire the richly ornamented houses, lavish churches, and exquisite relics that proliferated during this era of prosperity, which contributed to Europe’s Renaissance. Explore vibrant Helsinki before setting sail for Turku, the former Finnish capital founded in the 13th century, to discover its ancient castle and cathedral. Experience the rare delight of sailing into the Stockholm archipelago in the morning, wending through hundreds of small islands dotted with 19th- century homes and stately villas. Navigate narrow straits and gaze upon pine forests, imposing cliffs, and shores where grey seals and moose roam. In Stockholm, gain exclusive access to the city’s finest museums. HIGHLIGHTS Drift over to Visby, Sweden, one of ENJOY a private reception at Stockholm’s Vasa Scandinavia’s best-preserved medieval cities, Museum, housing the only preserved 17th-century and call at historic Gdańsk, a Polish seaport ship in the world, and marvel at the unspoiled with iconic rows of tall, multicolored Gothic detail of the vessel’s wood carvings and ornaments façades. In Germany, wander Hamburg and whimsical Lübeck, known as the “Queen City” DELIGHT in a private after-hours visit to of the Hanseatic League, which still houses the Millesgården, a sculpture garden and museum gabled mansions of the wealthy merchant class. -

Swedish Shipping Gazette DSM19 Edition

Swedish Shipping Swedish Shipping Gazette DSM19 Edition DSM19: Green tech Produced by in shipping Swedish Shipping Gazette DSM 19 Edition Our skillOur skill - your– your benefitbenefit Scanunit.se [email protected] +46 42 373350 Swedish Shipping Gazette Published by: Svensk Sjöfarts Tidnings Förlag AB, a subsidiary of the Swedish Shipowners’ Association (Föreningen Svensk Sjöfart). Editor in chief and publisher: Pär-Henrik Sjöström, +46-70-877 26 47 Welcome to Stockholm Repairyard Address: Västra Hamngatan 13, SE-411 17 Göteborg, Sweden Phone: +46-31-712 17 50 We carrycarry out out all all types types of shipof ship repair repair, and mainretrofit,- • •Dry Dry docks docks 180 180 m m xx 2525 mm andand 100 m x 16,5 m E-mail: [email protected] modificationtenance works. Withand ourmaintenance dry-docks andworks. the With • •Cranes Cranes range range fromfrom 12-12 - 3535 tons tons E-mail (staff): [email protected] Internet: www.sjofartstidningen.se ourstrategic dry-docks location and of thethe strategicyard we offer location excellent of the • •Berth Berth 75 75 m m with with aa depthdepth of 55 m yard we offer excellent availability and service • Berth 110 m with a depth of 7 m availability and service to our customers in the • Berth 110 m with a depth of 7 m ■ EDITORIAL STAFF to our customers in the region of Stockholm Pär-Henrik Sjöström, editor in chief +46-70-877 26 47 region of Stockholm and the Baltic Sea. Don’t hesitate to contact us, we are available and the Baltic Sea. Don’t hesitate to contact us, we are available Anna Lundberg, editor +46-73-642 38 11 2424 hourshours when when necessary. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. -

Hain Rebas Gbg, Oct 3Rd, 2010

1 Hain Rebas Gbg, Oct 3rd, 2010 Frustration and Revenge? Gotland strikes back - during the long 15th Century, 1390’s -1525.1 1. Agenda After having enjoyed increasing prosperity from the time of the Viking Age, the overseas commerce of the Gotlanders and the Visby traders began to decline sometime around the beginning of the 14th century. Navigation and ships improved, trade routes changed. Waves of unrest and pestilence around 1350, followed by the Danish violent conquest 1361, slowed down business even more. In the following years the Danish king rigorously contested Hanseatic supremacy at sea, but was definitively beaten 1370. Then the lines of royal succession became blurred both in Denmark and Norway, as well as in Sweden. The following rumbling and warring for the Scandinavian thrones, with Mecklenburgers and Hanseats actively involved, further reduced Gotlandic/Visbyensic positions in Baltic Sea matters. Finally in 1402 the Gotlanders were compelled to lease out their centuries- old trading station (Faktorei) Gotenhof in Novgorod, i.e. their pivot point on the lucrative Russian market, mercatura ruthenica, to the newly emergent Reval/Tallinn. Questions: Could the subsequent dramatic history, beginning with the arrival of the Vitalian Brethren in the early 1390s on the island, and ending with Lübeck’s sacco di Visby 1525, be defined as outbursts of Gotland frustration and attempts at come-back, even revenge? Can we identify a line of continuity whereby this prolonged 15th century is essentially a continuing story, instead of a rhapsodic chain of single, more or less ad hoc-events?2 In short: We know quite well what happened. -

Environmental Archaeology Current Theoretical and Methodological Approaches Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology

Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology Evangelia Pişkin · Arkadiusz Marciniak Marta Bartkowiak Editors Environmental Archaeology Current Theoretical and Methodological Approaches Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology Series editor Jelmer Eerkens University of California, Davis Davis, CA, USA More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/6090 Evangelia Pişkin • Arkadiusz Marciniak Marta Bartkowiak Editors Environmental Archaeology Current Theoretical and Methodological Approaches Editors Evangelia Pişkin Arkadiusz Marciniak Department of Settlement Archaeology Institute of Archaeology Middle East Technical University Adam Mickiewicz University Ankara, Turkey Poznań, Poland Marta Bartkowiak Institute of Archaeology Adam Mickiewicz University Poznań, Poland ISSN 1568-2722 Interdisciplinary Contributions to Archaeology ISBN 978-3-319-75081-1 ISBN 978-3-319-75082-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75082-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018936129 © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

With Sword and Mace? Searching for Blunt Force Trauma from the Cranial Material of the Battle of Good Friday

With sword and mace? Searching for blunt force trauma from the cranial material of the Battle of Good Friday Anniina Laine Master’s thesis Masterkurs i osteoarkeologi, 30 hp Supervisor: Anna Kjellström Co-supervisor: Astrid Noterman Stockholm University 2020 Abstract The crania from a mass grave associated to the Battle of Good Friday (1520) in Uppsala were re-examined in this study. The total skeletal material has been analysed before, but blunt force trauma was excluded and therefore a comprehensive trauma pattern could not be presented. In the current study, the perimortem cranial weapon-related trauma was examined by reconstructing the crania and conducting a trauma analysis. Standardised methods were used to identify and document blunt, sharp and puncture trauma. The results reveal that new blunt and sharp force trauma as well as one puncture trauma could be identified. Furthermore, the majority of weapon-related trauma were identified as sharp injuries, less than ten percent as blunt injuries and a few as puncture injuries. The cranial trauma pattern is interpreted to reflect the battle tactics, the situations in the battle, as well as the armour and weapons used by the soldiers. The notion of sharp force injuries forming the majority of trauma could imply that bladed weapons were used the most and blunt weapons were used less or caused less injuries visible on bone. The dominance of cranial trauma might indicate that head was a primary target. The trauma pattern implies that blunt weapons were used at least in face-to-face combat and bladed weapons were used in a variety of situations from face-to-face fight to more chaotic situations and against fleeing soldiers. -

Thanatourism Theming As a Sustainability Strategy at Gotlands Museum

Death Sells: Thanatourism Theming as a Sustainability Strategy at Gotlands Museum Master Thesis in Sustainable Destination Development Uppsala University, Campus Gotland Katherine Uziallo Supervisors: Camilla Asplund Ingemark Carina Johansson Spring Semester 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 3 1.1 Statement of purpose .................................................................................................................... 3 Delimitations of study ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Gotlands Museum background ..................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Material and method ..................................................................................................................... 6 Interviews ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Observation .................................................................................................................................... 8 Documents .................................................................................................................................... 10 1.4 History of research ...................................................................................................................... 10 History -

Annual Report 2019

Annual Report 2019 1865 – 2019 Vessel positions 30 March 2020 (also page 43). M/S VISBORG M/S VISBY M/S DROTTEN HSC GOTLANDIA HSC GOTLANDIA II M/S GUTE M/S GOTLAND Annual Report 2019 Contents www.gotlandsbolaget.se/en – www.gotlandtankers.se/en An extraordinary situation ....................................4 Rescue boat Eric D. Nilsson .................................5 Business concept and vision ............................6–7 Environment and the natural cycle ...................8–9 Destination Gotland ..................................... 10–11 Gotland Tankers .................................................12 GotlandsResor ...................................................13 Stockholms Reparationsvarv .............................14 www.destinationgotland.se Gotlands Stuveri ................................................15 The share and development ......................... 16–17 Board of Directors’ report ............................ 18–19 The business in brief – Group .............................20 Income statement 2019 .....................................21 Balance sheet as at 31 December 2019........ 22–23 Statement of changes in equity .........................24 Cash flow statements ........................................25 www.gotlandsresor.se Accounting and valuation policies................26–27 Notes to the consolidated and Parent Company financial statements ........ 28–35 Audit Report .................................................36–37 Board of Directors ..............................................38 Vessel -

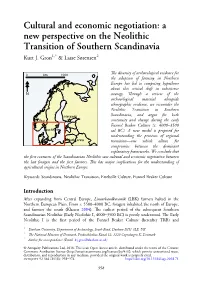

A New Perspective on the Neolithic Transition of Southern Scandinavia Kurt J

Cultural and economic negotiation: a new perspective on the Neolithic Transition of Southern Scandinavia Kurt J. Gron1,* & Lasse Sørensen2 0 km 1000 The diversity of archaeological evidence for the adoption of farming in Northern Europe has led to competing hypotheses about this critical shift in subsistence N strategy. Through a review of the archaeological material alongside ethnographic evidence, we reconsider the Neolithic Transition in Southern Helsinki Scandinavia, and argue for both Olso continuity and change during the early Funnel Beaker Culture (c. 4000–3500 Stockholm cal BC). A new model is proposed for understanding the processes of regional Study area transition—one which allows for compromise between the dominant explanatory frameworks. We conclude that the first centuries of the Scandinavian Neolithic saw cultural and economic negotiation between the last foragers and the first farmers. This has major implications for the understanding of agricultural origins in Northern Europe. Keywords: Scandinavia, Neolithic Transition, Ertebølle Culture, Funnel Beaker Culture Introduction After expanding from Central Europe, Linearbandkeramik (LBK) farmers halted in the Northern European Plain. From c.5500–4000 BC, foragers inhabited the north of Europe, and farmers the south (Klassen 2004). The earliest period of the subsequent Southern Scandinavian Neolithic (Early Neolithic I, 4000–3500 BC) is poorly understood. The Early Neolithic I is the first period of the Funnel Beaker Culture (hereafter TRB) and 1 Durham University, Department of Archaeology, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 2 The National Museum of Denmark, Frederiksholms Kanal 12, 1220 Copenhagen K, Denmark * Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) © Antiquity Publications Ltd, 2018. -

Dutch Royal Family

Dutch Royal Family A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 08 Nov 2013 22:31:29 UTC Contents Articles Dutch monarchs family tree 1 Chalon-Arlay 6 Philibert of Chalon 8 Claudia of Chalon 9 Henry III of Nassau-Breda 10 René of Chalon 14 House of Nassau 16 Johann V of Nassau-Vianden-Dietz 34 William I, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg 35 Juliana of Stolberg 37 William the Silent 39 John VI, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg 53 Philip William, Prince of Orange 56 Maurice, Prince of Orange 58 Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange 63 Amalia of Solms-Braunfels 67 Ernest Casimir I, Count of Nassau-Dietz 70 William II, Prince of Orange 73 Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange 77 Charles I of England 80 Countess Albertine Agnes of Nassau 107 William Frederick, Prince of Nassau-Dietz 110 William III of England 114 Mary II of England 133 Henry Casimir II, Prince of Nassau-Dietz 143 John William III, Duke of Saxe-Eisenach 145 John William Friso, Prince of Orange 147 Landgravine Marie Louise of Hesse-Kassel 150 Princess Amalia of Nassau-Dietz 155 Frederick, Hereditary Prince of Baden-Durlach 158 William IV, Prince of Orange 159 Anne, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange 163 George II of Great Britain 167 Princess Carolina of Orange-Nassau 184 Charles Christian, Prince of Nassau-Weilburg 186 William V, Prince of Orange 188 Wilhelmina of Prussia, Princess of Orange 192 Princess Louise of Orange-Nassau 195 William I of the Netherlands -

Annual Report 2018

Annual Report 2018 1865 – 2018 HSC Gotlandia II HSC Gotlandia M/S Gotland M/S Visby M/S Visborg M/S Gute M/T Gotland Marieann M/T Gotland Carolina M/T Alice M/T Gotland Sofia M/S Thjelvar M/T Wisby Atlantic M/T Ami M/S Cielo di Tocopilla M/T Wisby Pacific M/T Gotland Aliya M/S Cielo di Jari Vessel positions 28 March 2019 (also page 43) Annual Report 2018 www.gotlandsbolaget.se/en – www.gotlandtankers.se/en Contents Letter to Shareholders .........................................4 The financial year in brief .....................................5 Business concept and vision ............................6–7 Environment ....................................................8–9 Staff and employees .................................... 10–11 www.destinationgotland.se/en The Gotland service ..................................... 12–13 Companies and businesses ......................... 14–15 The share and development ......................... 16–17 Board of Directors’ report ............................. 18–19 The business in brief – Group .............................20 Income statement 2018 .....................................21 Balance sheet as at 31 December 2018........ 22–23 www.gotlandsresor.se Statement of changes in equity .........................24 Cash flow statements ........................................25 Accounting and valuation policies................26–27 Notes to the consolidated and Parent Company financial statements .........28–35 Audit Report .................................................36–37 Vessel Gallery ..............................................38–41 -

2467 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Oxley

2467 Soldiers, Sailors and Marines Oxley OXLEY, CLARENCE MILLER. Army number 501,007; not a registrant, under age; born, Cogswell, N. Dak., July 31, 1899, of American parents; occupation, farmer; enlisted at Des Moines, Iowa, on Feb. 4, 1918; sent to Fort Logan, Colo.; served in Battery C, 11th Field Artillery, to discharge; overseas from July 16, 1918, to June 10, 1919. Discharged at Camp Dodge, Iowa, on June 18, 1919, as a Private. OXLEY, ELMER LEAVITT. Navy number 1,743,142; not a registrant, enlisted prior; born, Maxwell, Iowa, Feb. 4, 1896, of American parents; occupation, locomotive fireman; enlisted in the Navy at Miles City, Mont., on May 26, 1917; served at Naval Training Station, San Francisco, Calif., to June 29, 1917; Naval Training Camp, San Diego, Calif., to Feb. 5, 1918; Operating Base, Norfolk, Va., to Feb. 23, 1918; USS Wisconsin, to March 15, 1918; Receiving Ship, Norfolk, Va., to March 23, 1918; USS Lake Bridge, to April 20, 1918; Receiving Ship, Norfolk, Va., to May 3, 1918; USS Mars, to Nov. 11, 1918. Grades: Apprentice Seaman, 31 days; Seaman 2nd Class, 126 days; Fireman 3rd Class, 377 days. Discharged at Minneapolis, Minn., on Aug. 11, 1919, as a Baker 1st Class. OXTOBY, JOHN RICHARD. Army number 3,950,511; registrant, Dickey county; born, Altavista, Kans., Aug. 2, 1886, of American-English parents; occupation, mail carrier; inducted at Ellendale on Aug. 27, 1918; sent to Camp Lewis, Wash.; served in Company D, 76th Infantry, to discharge. Grade: Private 1st Class, Dec. 1, 1918. Discharged at Camp Lewis, Wash., on Jan.