Journal of Eurasian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr.Shyamal Kanti Mallick Designation

Dr.Shyamal Kanti Mallick M.Sc,B.Ed., Ph.D.,FTE Designation: Associate Professor Department: Botany Ramananda College, Bishnupur Bankura, West Bengal, India E-mail:[email protected] AREAS OF INTEREST/SPECIALISATION • Ecology and Taxonomy of Angiosperms • Ethnobotany • Plant diversity ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENTS • B.Sc. (Hons.in Botany) degree from Vidyasagar University • M. Sc.( Botany) degree from Vidyasagar University • Ph,D. ( Botany) degree from Vidyasagar University RESEARCH EXPERIENCE From To Name and Address of Funding Position held Agency / Organization 1997 2002 Vidyasagar University Scholar 2008 2020 Burdwan University & Project Supervisor at Bankura University PG level 2017 Till date Bankura University Ph.D. Supervisor ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE • Teaching experience at H.S. School level from 10.12.91 to 21.03.2005 • Teaching experience at UG level from 22.03.2005 to till date • Teaching experience at PG level from 2008 to till date • PG level Supervisor from 2008 to till date • Ph. D. Level Supervisor from 28.11.17 to till date ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE • PGBS Member of Burdwan University • UGBS & PGBS Member of Bankura University • Departmental Head of Ramananda College from 01.07.2012 to30.06.2014 • Syllabus Committee ( P.G.) of Midnapore College ( Autonomous) • Member of Ph.D. committee of Bankura University. PUBLICATIONS (List of Journals/Proceedings/Chapter in Books) 1. Mukherjee,S. and Mallick, S.K.(2020 ). An Ethnobotanica study of Ajodhya Forest Range of Purulia District, West Bengal. “Asian Resonance ” 9(4): 104-107. 2. Mallick, S.K.(2020 ). An Ethnobotanical stydy on Tajpur Village of Bankura District “Asian Resonance ” 9(3): 1-6. 3. Mallick, S.K.(2017 ). -

Report on Mainamati- Zinat Afrose

Mainamati: Greatest Assemblage of Ancient Buddhist Settlements Zinat Afrose Introduction: The Mainamati-Lalmai range, an isolated low, dimpled range of hills dotted with more than 50 ancient Buddhist settlements from the 8th to 12th centuries A.D., runs through the heart of the Cumilla district. The wealthiest region of Bangladesh is Mainamati, Cumilla, which is home to the majority of the country's heritage sites. Shalban Bihara, located almost in the middle of the Mainamati Lalmai hill range, is made up of 115 cells arranged around a spacious courtyard with a cruciform temple in the centre facing its only gateway complex to the north which is similar to that of Paharpur Monastery. Kutila Mura is a charming Buddhist establishment located on a flattened hillock about 5 km north of Shalban Vihara within the Cumilla Cantonment. Three stupas stand side by side, symbolizing the Buddhist 'Trinity,' or three jewels, which are the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Charpatra Mura is a small oblong shrine located 2.5 kilometres northwest of the Kutila Mura stupas. The shrine is approached from the east via a gateway that leads to a large hall. Copper plates, gold and silver coins, and 86 bronze artefacts are among the many items on display at the Mainamati site museum. About 150 bronze statues, mostly from monastic cells, bronze stupas, stone sculptures, and hundreds of terracotta plaques have been found, each measuring 9" high and 8" to 12" wide on average. https://steemit.com/walkwithme/@boishakhitripty/walkwithme-to-moinamoti-buddhists-settlement Mainamati, an isolated ridge of low hills on the eastern margins of deltaic Bangladesh, about 8 excavations have uncovered important materials. -

Registration Form Inviting You to the PHYSICON-2019: the XXXI S T Annual Discussion Will Be Under the Following Heads

OUTLINE OF THE PROGRAMME Places of Interest Near Bankura PHYSICON-2019 PHYSICON-2019 will discuss the importance of Physiology PHYSICON-2019 as a basic science to promote teaching and research. The Mukutmanipur is nearby conference will have technical sessions including key note major tourist attractions in st XXXI Annual Conference of the Physiological Society of India address by eminent scientists, symposium, seminar, oral Khatra subdivision. The XXXI Annual Conference of the Physiological Society of India th th ANNOUNCEMENT/ INVITATION and poster presentations. In addition, a number of second biggest earth dam of 15 – 17 November, 2019 Dear Colleagues, distinguished speakers will deliver orations conferred by I n d i a i s l o c a t e d i n On behalf of the Organizing Committee, it is a great pleasure in the Physiological Society of India (PSI). The topics of Mukutmanipur 55 km away Registration Form inviting you to the PHYSICON-2019: The XXXI s t Annual discussion will be under the following heads. from Bankura Conference of the Physiological Society of India (PSI) “Recent Name: Prof./Dr./Mr./Ms……………………………………………... Trends in Physiology and Healthcare Research for Salubrious Cardiovascular Physiology Designation………………………………………………………………… Society” held at the Bankura Christian College, Bankura- Respiratory Physiology Susunia Hill (1,200 ft.) is a th th Department:…………………………………………………..………….. 722101, West Bengal, India, during 15 – 17 November, 2019. Renal Physiology known archeological and Institution….……………………………………………..………………… Bankura Christian College as a premier higher education GI Physiology fossil site. It is a place of institution is now a brand name in academia. The college has archaeological interest and a City………………………........….. -

CBCS-HISTORY-PG-SYLLABUS.Pdf

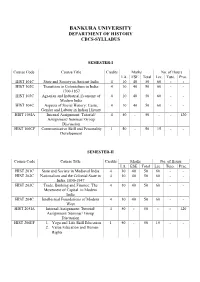

BANKURA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CBCS-SYLLABUS SEMESTER-I Course Code Course Title Credits Marks No. of Hours I.A. ESE Total Lec. Tuto. Prac. HIST 101C State and Society in Ancient India 4 10 40 50 60 - - HIST 102C Transition to Colonialism in India: 4 10 40 50 60 - - 1700-1857 HIST 103C Agrarian and Industrial Economy of 4 10 40 50 60 - - Modern India HIST 104C Aspects of Social History: Caste, 4 10 40 50 60 - - Gender and Labour in Indian History HIST 105IA Internal Assignment: Tutorial/ 4 50 - 50 - - 120 Assignment/ Seminar/ Group Discussion HIST 106CF Communicative Skill and Personality 1 50 - 50 15 - - Development SEMESTER-II Course Code Course Title Credits Marks No. of Hours I.A. ESE Total Lec. Tuto. Prac. HIST 201C State and Society in Medieval India 4 10 40 50 60 - - HIST 202C Nationalism and the Colonial State in 4 10 40 50 60 - - India: 1858-1947 HIST 203C Trade, Banking and Finance: The 4 10 40 50 60 - - Movement of Capital in Modern India HIST 204C Intellectual Foundations of Modern 4 10 40 50 60 - - West HIST 205IA Internal Assignment: Tutorial/ 4 50 - 50 - - 120 Assignment/ Seminar/ Group Discussion HIST 206EF 1. Yoga and Life Skill Education 1 50 - 50 15 - - 2. Value Education and Human Rights SEMESTER-III Course Course Title Credits Marks No. of Hours Code I.A. ESE Total Lec. Tuto. Prac. HIST 301C Historiography and 4 10 40 50 60 - - Historical Methods HIST 302C Birth of the Modern 4 10 40 50 60 - - World: Capitalism and Colonialism in Historical Perspective HIST Colonialism and its 4 10 40 50 60 - - 303EA Impact on Indian Society and Culture HIST Crime, Law and Society 4 10 40 50 60 304EIDA in Colonial India HIST304 Studies in Literary 4 10 40 50 60 - - EIDB Culture and Identities in Modern India HIST Dissertation , viva voce 4 - - 30+20=50 - - 120+15(Library) 305IA (D,V) SEMESTER-IV Course Course Title Credits Marks No. -

Journal of History

Vol-I. ' ",', " .1996-97 • /1 'I;:'" " : ",. I ; \ '> VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Journal of History S.C.Mukllopadhyay Editor-in-Chief ~artment of History Vidyasagar University Midnapore-721102 West Bengal : India --------------~ ------------ ---.........------ I I j:;;..blished in June,1997 ©Vidyasagar University Copyright in articles rests with respective authors Edi10rial Board ::::.C.Mukhopadhyay Editor-in-Chief K.K.Chaudhuri Managing Editor G.C.Roy Member Sham ita Sarkar Member Arabinda Samanta Member Advisory Board • Prof.Sumit Sarkar (Delhi University) 1 Prof. Zahiruddin Malik (Aligarh Muslim University) .. <'Jut". Premanshu Bandyopadhyay (Calcutta University) . hof. Basudeb Chatterjee (Netaji institute for Asian Studies) "hof. Bhaskar Chatterjee (Burdwan University) Prof. B.K. Roy (L.N. Mithila University, Darbhanga) r Prof. K.S. Behera (Utkal University) } Prof. AF. Salauddin Ahmed (Dacca University) Prof. Mahammad Shafi (Rajshahi University) Price Rs. 25. 00 Published by Dr. K.K. Das, Registrar, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore· 721102, W. Bengal, India, and Printed by N. B. Laser Writer, p. 51 Saratpalli, Midnapore. (ii) ..., -~- ._----~~------ ---------------------------- \ \ i ~ditorial (v) Our contributors (vi) 1-KK.Chaudhuri, 'Itlhasa' in Early India :Towards an Understanding in Concepts 1 2.Bhaskar Chatterjee, Early Maritime History of the Kalingas 10 3.Animesh Kanti Pal, In Search of Ancient Tamralipta 16 4.Mahammad Shafi, Lost Fortune of Dacca in the 18th. Century 21 5.Sudipta Mukherjee (Chakraborty), Insurrection of Barabhum -

History Honours Syllabus

CBCS SYLLABUS for B.A (HONOURS) IN HISTORY (w.e.f. 2017) BANKURA UNIVERSITY BANKURA WEST BENGAL PIN 722155 Bankura University B.A.(Honours) History CBCS w.e.f. 2017-18 CBCS SYLLABUS For B.A (HONOURS) IN HISTORY (w.e.f. 2017) SEMESTER WISE COURSE STRUCTURE TOTAL MARKS =1300 SEMESTER - 6 CREDITS =142 COURSES SEM SEM SEM SEM SEM SEM TOTAL I II III IV V VI CORE COURSES 12 12 18 18 12 12 84 DISCIPLINE SPECIFIC - - - - 12 12 24 ELECTIVE COURSE GENERIC ELECTIVE / INTERDICIPLINARY 6 6 6 6 - - 24 COURSE ABILITY ENHANCEMENT 4 2 - - - - 6 COMPULSORY COURSE (AECC) SKILL - - 2 2 - - 4 ENHANCEMENT COURSES (SEC) TOTAL 22 20 26 26 24 24 142 Bankura University B.A.(Honours) History CBCS w.e.f. 2017-18 THE DISTRIBUTION OF CREDITS FOR DIFFERENT CATEGORIES OF COURSES STRUCTURE FOR HISTORY (HIST) HONOURS Marks Total Semester Courses Credits I.A ESE 1st Sem. 2 Core Courses of 6 Credits Each 2 × 6 = 12 2 × 10 = 20 2 × 40 = 80 1 Generic Elective of 6 Credits 1 × 6 = 6 1 × 10 = 10 1 × 40 = 40 200 1 EnvironmentalStudies of 4 credits 1 × 4 = 4 1 × 10 = 10 1 × 40 = 40 2nd Sem. 2 Core Courses of 6 Credits Each 2 × 6 = 12 2 × 10 = 20 2 × 40 = 80 1 Generic Elective of 6 Credits 1 × 6 = 6 1 × 10 = 10 1 × 40 = 40 200 1 English/Hindi/MILCommunication of 2 1 × 2 = 2 1 × 10 = 10 1 × 40 = 40 Credits 3Core Courses of 6 Credits Each 3 × 6 = 18 3 × 10 = 30 3 × 40 = 120 rd 3 Sem. -

Bankura University

BANKURA UNIVERSITY (West Bengal Act XIX of 2013- Bankura University Act, 2013) Main Campus, Bankura Block-II, P.O.: Purandarpur, Dist.: Bankura, Pin- 722155, West Bengal Office of the Council for Undergraduate Studies in Arts & Science Bankura University NOTIFICATION The meeting with all the Principal/OIC/TIC of the colleges affiliated under Bankura University dated 14.07.2021 along with members of the Admission committee for UG studies have approved the said recommendations for implementation/execution in the undergraduate colleges for admission procedures in the session 2021-2022. The recommendation pertaining to admission related different issues are as follows: Choice Based Credit System: 1. Choice Based Credit System will be maintained for the academic session 2021-2022. Procedure of Admission: 1. Necessary advertisement for on-line admission to the undergraduate course(s) for the academic year 2021-2022 will be made by the respective undergraduate colleges of their own. Online admission will be made w.e.f 2nd August, 2021 and be completed by 30th September, 2021. The colleges will provide a helpline (Time specific) in their website in this regard. 2. The entire admission process should be made online. 3. Documents to be uploaded by the students while filling up the online application: a. Admit card and Mark-sheet of Madhyamik Examination. b. Mark-sheet of Higher Secondary Examination. c. Caste Certificate (where necessary). d. PH Certificate (where necessary). 4. All orders & notifications issued by the State Government and G.O. N.O. 706- Edn(CS)/10M-95/14 dated 13.07.2021 are applicable in matters of admission and reservation rules. -

Lion Symbol in Hindu-Buddhist Sociological Art and Architecture of Bangladesh: an Analysis

International Journal in Management and Social Science Volume 08 Issue 07, July 2020 ISSN: 2321-1784 Impact Factor: 6.178 Journal Homepage: http://ijmr.net.in, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal Lion Symbol in Hindu-Buddhist Sociological Art and Architecture of Bangladesh: An Analysis Sk. Zohirul Islam1, Md. Kohinoor Hossain2, Mst. Shamsun Naher3 Abstract There is no lion animal in Bangladesh still live but has a lot of sculptors through terracotta art in architecture, which are specially used as decorative as religious aspects through the ages. The lion is the king of the animal world. They live in the plain and grassy hills particularly. Due to these characteristics, the lion has been considered through all ages in the world as a symbol of royalty and protection as well as of wisdom and pride, especially in Hindu- Buddhist religion. In Buddhism, lions are symbolic of the Bodhisattvas. In Buddhist architecture, lion symbols are used as protectors of Dharma and therefore support the throne of the Buddha’s and Bodhisattvas. The lion symbol is also used in Hindu temple architecture as Jora Shiva Temple, Akhrapara Mondir of Jashore. In Bangladesh, there are various types of lion symbol used in terracotta plaques of Ananda Vihara, Rupbhan Mura, and Shalban Vihara at Mainamati in Comilla district, Vashu Vihara, Mankalir Kundo at Mahasthangarh in Bogra district and Somapura Mahavihara at Paharpur in Naogaon district. This research has been trying to find out the cultural significance of the lion symbol in Hindu-Buddhist art and architecture of Bangladesh. -

Mandsaur PDF\2316

CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 MADHYA PRADESH SERIES -24 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK MANDSAUR VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MADHYA PRADESH 2011 INDIA MADHYA PRADESH DISTRICT MANDSAUR To Kota To Chittorgarh N KILOMETRES To Kota !GANDHI SAGAR 4 2 0 4 8 12 16 HYDEL COLONY A C.D. B L O C K From Rampura B H A N P U R A H G To Kota A ! Sandhara BHANPURA To C Jhalrapatan ! J H U RS . R l J a b M !! Bhensoda ! ! ! ! m ! ! ! a ! h ! C ! ! E ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! From Neemuch ! ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! I ! ! E ! ! T T C ! T N From Ajmer S C To Mandsaur I GAROTH RS ! ! ! J ( D ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MALHARGARH ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! From Jiran ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! C.D. B L O C K G ! A R O T H ! ! ( NARAYANGARH ! G ! ! R ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Boliya ! B ! To Kotri ! ! G !! ! ! ! Budha ! S ! ! ! RS ! ! ! ! ! D ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Chandwasa C.D. B L O C K M A L H A R G A R H ! ! ! . ! ! ! ! SHAMGARH Sh a R ! ! i vn ! N PIPLYA MANDI ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! R RS G ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! J ! ! RS ! ! ! Nahargarh ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! . ! ! ! ! ! ! ! RS ! G ! ! ! ! R A ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! l ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! a ! NH79 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! b ! ! ! ! ! ! ! m ! G ! ! ! a ! ! ! ! )M ! Kayampur h ! Multanpura ! H C A ! ! G)E ! SUWASRA H ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MANDSAUR ! G R ! RS P ! ! ! ( ! ! ! ! ! ! SH 14 ! C.D. B L O C K S I T A M A U ! ! E ! T ! ! SITAMAU ! Kilchipura !! ! ! ( R From ! ! ! ! G ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Pratappur ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Ladoona ! ! ! ! ! J ! ! ! S ! ! -

Artuklu Human and Social Science Journal

Artuklu Human and Social Science Journal ARTICLE http://dergipark.gov.tr/itbhssj The Formation of Bengal Civilization: A Glimpse on the Socio-Cultural Assimilations Through Political Progressions Key words: in Bengal Delta 1. Bengal Delta Abu Bakar Siddiq1 and Ahsan Habib2 2. Socio-cultural Abstract assimilation The Bengal Delta is a place of many migrations, cultural transformations, invasions 3. Aryan and religious revolutions since prehistoric time. With the help of archaeological and historical records, this essay present the hypothesis that, albeit there were multiple 4. Mauryan waves of large and small scale socio-cultural assimilations, every socio-political 5. Medieval period change did not brought equal formidable outcome in the Delta. The study further illustrates that, the majority of cultural components were formulated by Indigenous- Aryan-Buddhist assimilations in early phase, whereas the Buddhist-Aryan-Islamic admixtures in relatively forbearing and gracious socio-political background of medieval period contributed the final part in the formation of Bengal Civilization. INTRODUCTION one of the most crowed human populations in the world The Bengal Delta (i.e. present Bangladesh and West with a density of more than 1100 people per square mile. Bengal in India) is the largest delta in the world (Akter The physiological features of Bengal delta is completely et al., 2016). Annual silt of hundreds of rivers together river based. River has tremendous effect on the with a maze of river branches all over this Green Delta formation of landscape, agriculture and other basic made it as one of the most fertile regions in the world. subsistence, trade and transport, as well as cultural Additionally, amazing landscape, profound natural pattern of its inhabitants. -

Elemental Analysis of Old Mortar Used in Various Archaeological Sites of Bangladesh by Sem and Edax

J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh, Sci. 38(2): 145-153, December 2012 ELEMENTAL ANALYSIS OF OLD MORTAR USED IN VARIOUS ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES OF BANGLADESH BY SEM AND EDAX ACHIA KHANOM1,*D. K. SAHA2, S. M. RAHAMAN1 AND AL MAMUN2 1Department of Archaeology, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka 2Materials Science Division, Atomic Energy Centre, Dhaka-1000 Abstract Morphological characterization and mineralogical studies were performed on fifteen mortar samples collected from three ancient archaeological sites (Wari-Bateshwar, Lalmai-Mainamati, and Paharpur) of Bangladesh. Many cracks and pores were found in the mortar samples of Buddhist Lotus temple of Wari-Bateshwar. Energy dispersive analytical x-ray analysis confirmed the presence of C, O, P, K, Al, Fe, Na, Mg, Mn, Si and Ti in the mortar samples. The absence of Ca in the samples indicates that the clay was used in the architecture as binding materials. In the clay mortar, Si played an important role and with the presence of O2, SiO2 was formed, which strengthened the binder. K, Al, Fe, Na, Mg, Mn, Si and Ti might form compounds like SiO2, Fe2O3, K2O, +2 Al2O3, MgO, MnO, Na2O3, and TiO2 with O2. The oxidation of Fe produced Fe2O3 which was responsible for breaking down the bonding of mortars. Key words: Archaeology, Mortar, Deterioration, SEM and EDAX Introduction Mortar analysis is an essential domain for conservation of architectural remains of Bangladesh. Mortar, a workable paste, generally formed by the mixture of cement, sand and water, is a fine aggregate to fill the gaps between construction bricks and stones. Aziz (1995) classified the types of mortar as follows (i) mud mortar (ii) lime mortar (iii) surki mortar (iv) lime surki mortar and (v) cement mortar. -

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-Aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt. No. 1/2018) Bengali UR OBC-A OBC-B SC ST PWD 43 13 1 30 25 6 Sl No College University UR 1 Bankura Zilla Saradamoni Mahila Mahavidyalaya 2 Khatra Adibasi Mahavidyalaya. 3 Panchmura Mahavidyalaya. BANKURA UNIVERSITY 4 Pandit Raghunath Murmu Smriti Mahavidyalaya.(1986) 5 Saltora Netaji Centenary College 6 Sonamukhi College 7 Hiralal Bhakat College 8 Kabi Joydeb Mahavidyalaya 9 Kandra Radhakanta Kundu Mahavidyalaya BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 10 Mankar College 11 Netaji Mahavidyalaya 12 New Alipore College CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY 13 Balurghat Mahila Mahavidyalaya 14 Chanchal College 15 Gangarampur College 16 Harishchandrapur College GOUR BANGA UNIVERSITY 17 Kaliyaganj College 18 Malda College 19 Malda Women's College 20 Pakuahat Degree College 21 Jangipur College 22 Krishnath College 23 Lalgola College KALYANI UNIVERSITY 24 Sewnarayan Rameswar Fatepuria College 25 Srikrishna College 26 Michael Madhusudan Memorial College KAZI NAZRUL UNIVERSITY (ASANSOL) 27 Alipurduar College 28 Falakata College 29 Ghoshpukur College NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY 30 Siliguri College 31 Vivekananda College, Alipurduar 32 Mahatma Gandhi College SIDHO KANHO BIRSHA UNIVERSITY 33 Panchakot Mahavidyalaya 34 Bhatter College, Dantan 35 Bhatter College, Dantan 36 Debra Thana Sahid Kshudiram Smriti Mahavidyalaya VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 37 Hijli College 38 Mahishadal Raj College 39 Vivekananda Satavarshiki Mahavidyalaya 40 Dinabandhu