Bitter Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 Bibliography

2009 Green River Basin Plan II Bibliography AREA AUTHOR TITLE DATE Baggs Weston Groundwater Town of Baggs, Wyoming Alluvial Well Project, Executive Summary Jan, 2000 Engineering Town of Baggs, Wyoming Alluvial Well Project, Final Report Jan, 2000 Town of Baggs, Wyoming Water Supply Project Level II, Final Report Nov, 2000 AVI Town of Baggs, Wyoming Water Supply Project Level II, Executive Summary Nov, 2000 AVI Professional Town of Baggs, Wyoming Water Master Plan Level I, Executive Summary Nov, 2002 Corporation Town of Baggs, Wyoming Water Master Plan Level I, Final Report Nov, 2002 Baggs Water & Raw Water Supply Level II Report, Executive Summary Nov, 2004 Donnell & Allred, Inc. Baggs Water & Raw Water Supply Level II Report Nov, 2004 Bairoil Hydro-Search, Inc. Bairoil, Wyoming Groundwater Development Feasibility Exploration Program Nov, 1983 Executive Summary of Final Report, Bairoil Water Supply Project Level II May, 2000 Bairoil Water Supply Project Level II, Final Report May, 2000 Bairoil Water Supply Project Level II, Phase IV, Final Report Oct, 2001 Lidstone and Associates, Executive Summary of Final Report, Bairoil Water Supply Project Level II, Phase V May, 2003 Inc. Town of Bairoil Water Supply Project Level II, Phase V Report May, 2003 Big Jorgensen Engineering Big Piney/Marbleton Level II Water Supply Project Report, Final Report Nov, 1994 Piney/Marbleton and Land Surveying Big Piney/Marbleton Level II Water Supply Project Report, Executive Summary Nov, 1994 Big Sandy River Tipton and Kalmbach, Inc. Proposed Dam and Reservoir, Big Sandy Control Project Sep, 1982 Rick Blatchley Class III Archeological Investigations Conducted for the Big Sandy River Unit Desalinization Study Sweetwater County, Wyoming, Draft Nov, 1982 Greenhorne & O'Mara, Inc. -

Investigating Potential Solutions to the Barrier Effect of Interstate 80 on Pronghorn Movements

Final Report WY01/21 State of Wyoming Department of Transportation © 2018 Gregory Nickerson, Wyoming Migration Initiative Investigating Potential Solutions to the Barrier Effect of Interstate 80 on Pronghorn Movements By University of Wyoming 1000 East University Avenue, Dept. 3166 Laramie, Wyoming 82071 January 2021 Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) in the interest of information exchange. WYDOT assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. WYDOT does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trademarks or manufacturers’ names appear in this report only because they are considered essential to the objective of the document. Quality Assurance Statement WYDOT provides high-quality information to serve government, industry, and the public in a manner that promotes public understanding. Standards and policies are used to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of its information. WYDOT periodically reviews quality issues and adjusts its programs and processes to ensure continuous quality improvement. Copyright No copyrighted material, except that which falls under the “fair use” clause, may be incorporated into a report without permission from the copyright owner, if the copyright owner requires such. Prior use of the material in a WYDOT or governmental publication does not necessarily constitute permission to use it in a later publication. Courtesy – Acknowledgment or credit will be given by footnote, bibliographic reference, or a statement in the text for use of material contributed or assistance provided, even when a copyright notice is not applicable. Caveat for Unpublished Work – Some material may be protected under common law or equity even though no copyright notice is displayed on the material. -

Introduction to Greater Green River Basin Geology, Physiography, and History of Investigations

Introduction to Greater Green River Basin Geology, Physiography, and History of Investigations U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1506-A Introduction to Greater Green River Basin Geology, Physiography, and History of Investigations By HENRY W. ROEHLER GEOLOGY OF THE EOCENE WASATCH, GREEN RIVER, AND BRIDGER (WASHAKIE) FORMATIONS, GREATER GREEN RIVER BASIN, WYOMING, UTAH, AND COLORADO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1506-A UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1992 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, JR., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Roehler, Henry W. Introduction to greater Green River basin geology, physiography, and history of investigations / by Henry W. Roehler. p. cm. (Geology of the Eocene Wasatch, Green River, and Bridger (Washakie) formations, greater Green River basin, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado) (U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1506-A) Includes bibliographical references (p. ). Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.16:1506A 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Eocene. 2. Geology Green River Watershed (Wyo.-Utah). I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: U.S. Geological Survey professional paper ; 1506-A. QE692.2.R625 1992 551.7'84'097925 dc20 91-23181 CIP For sale by Book and Open-File Report Sales, U.S. Geological Survey, Federal Center, Box 25286, Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Page Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ Al Purpose and scope of investigation ............................................................................................ 1 Location and accessibility of the greater Green River basin ................................................... 2 Geologic setting ........................................................................................................................... -

Mineral Resources of the Adobe Town Wilderness Study Area, Sweetwater County, Wyoming

Mineral Resources of the Adobe Town Wilderness Study Area, Sweetwater County, Wyoming U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1757-H WYOMING BULLEITN 1757-H This document provided as a service f 7^-r Tfl-l'-^v-i!-';.-^ of tNafional ^^f^^s-y Water Wett Association, Dublin, Ohio. Chapter H Mineral Resources of the Adobe Town Wilderness Study Area, Sweetwater County, Wyoming By RICHARD E. VAN LOENEN, RANDALL H. HILL, VI Kl BAN KEY, and WILLIAM A. BRYANT U.S. Geological Survey R.F. KNESS U.S. Bureau of Mines NATIONAL GROUND WATER INFORMATION CENTER U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1757 MINERAL RESOURCES OF WILDERNESS STUDY AREAS SOUTHERN WYOMING DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, JR., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1990 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section U.S. Geological Survey Federal Center Box 25425 Denver, CO 80225 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mineral resources of the Adobe Town Wilderness Study Area, Sweetwater County, Wyoming / by Richard E. Van Loenen ... [et al.] p. cm. (Mineral resources of wilderness study areas southern Wyoming ; ch. H) (U.S. Geological Survey bulletin ; 1757-H) (Studies related to wilderness Bureau of Land Management wilderness study areas.) Includes bibliographical references. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.3:1757-H 1. Mines and mineral resources Wyoming Adobe Town Wilderness. 2. Adobe Town Wilderness (Wyo.) I. Van Loenen, Richard E. -

Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge

Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan September 2002 Prepared by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge P.O. Box 700 Green River, Wyoming 82935 and Division of Refuge Planning Region 6, Mountain-Prairie Region P.O. Box 25486, DFC Denver, Colorado 80225 Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Approval U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 6 s,.i1'-;",iJ-sf=- u." f\efu-ge Progn S~ &_"./C1. ~ Dats: R;;w;j A Vlli!JTl,J(l. ftl 0 1IegI(J1II1 O'ltel Nato:reI 'M1d"-1 Refuge Sy.;!edI TTTable of Contents SummarySummarySummary ............................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Photo Display .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 I.I.I. Introduction / Background Refuge Overview: History of Refuge Establishment, Acquisition and Management .......................................... 7 Seedskadee NWR Overview .................................................................................................................................. 7 History of Seedskadee NWR Establishment, Acquisition, and Management ................................................ 7 Purpose of and Need for Comprehensive Conservation Plan .................................................................................. 11 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service -

SWEETWATER COUNTY WYOMING Rock Springs & Green River

SWEETWATER COUNTY WYOMING Rock Springs & Green River Explore 100s of miles The of trails and shoreline. Flaming Soak up the sunshine Gorge and catch the “Big One.” tourwyoming.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 2-3 SWEETWATER COUNTY MAP 23-24 EVENTS CALENDAR 25-27 FLAMING GORGE COUNTRY 4-9 TOWNS 28 SEEDSKADEE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE 5 ROCK SPRINGS 29 PILOT BUTTE WILD HORSES 6 GREEN RIVER 7 SUPERIOR 30-37 INDOOR/OUTDOOR RECREATION & PARKS 7 WAMSUTTER 31 KILLPECKER SAND DUNES 8 HISTORIC SOUTH PASS 32 ATV/OHV 9 EDEN VALLEY 33 MOUNTAIN BIKING 9 INDUSTRY IN SWEETWATER COUNTY 34-35 ADVENTURES ON THE GREEN RIVER 35 GREEN RIVER RECREATION CENTER 10-16 HISTORY, MUSEUMS & TRAILS 36 ROLLING GREEN RIVER COUNTRY CLUB 11 ROCK SPRINGS HISTORICAL MUSEUM 36 WHITE MOUNTAIN GOLF COURSE 12 WWCC NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM 37 ROCK SPRINGS FAMILY RECREATION CENTER 13 SWEETWATER COUNTY HISTORICAL MUSEUM 37 ROCK SPRINGS CIVIC CENTER 14-15 HISTORIC PIONEER TRAILS 38 SWEETWATER COUNTY PARKS 16 COMMUNITY FINE ARTS CENTER 39 SCENIC DRIVES 17-29 SIGHTSEEING 40-42 ITINERARIES 18 ROCK FORMATIONS 43 GUIDED TOURS 19 WHITE MOUNTAIN PETROGLYPHS 44-45 NATIONAL PARKS 20 FOSSILS OF LAKE GOSIUTE 46-47 ACCOMMODATIONS 20 THE RELIANCE TIPPLE 48-52 DINING & NIGHTLIFE 21-22 SWEETWATER EVENTS COMPLEX ACTIVITY ICONS KEY SIGHTSEEING CAMPING FISHING HIKING BIKING GOLF WATER SPORTS TourWyoming.com create adventure The Best Vacations Don’t Just Happen When You Get There. They Happen Along the Way. Whether Sweetwater County is your final Wyoming destination or you’re visiting on the way to the National Parks, there are countless ways to create an adventure of your own. -

Chapter GS FORT UNION COAL in the GREATER GREEN RIVER BASIN, EAST FLANK of the ROCK SPRINGS UPLIFT, WYOMING

Chapter GS FORT UNION COAL IN THE GREATER GREEN RIVER BASIN, EAST FLANK OF THE ROCK SPRINGS UPLIFT, WYOMING: A SYNTHESIS By R.M. Flores and L.R. Bader in U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1625-A Contents Introduction...........................................................................................................................GS-1 History of Coal Mining......................................................................................................GS-3 Geological Setting................................................................................................................GS-6 Depositional Setting............................................................................................................GS-9 Coal Geology..................................................................................................................... GS-12 Coal Resources and Coal Quality.................................................................................. GS-14 Conclusions........................................................................................................................ GS-16 References .......................................................................................................................... GS-18 Figures GS-1. Generalized map of the Greater Green River Basin in south-central Wyoming showing associated basins, geologic structures, and surrounding mountains and uplifts. GS-2. Generalized geologic map of the Greater Green River Basin showing the Tertiary rocks and undifferentiated -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Reliance Tipple

NPS Form 10-900 (R«v. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Aral 9 1391 National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form RiGliTiR This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property ~""~~"~"""~"~~~~~"~ ~~~~ historic name Reliance Tipple other names/site number 48SW6461 2. Location street & number Section 36, T20N. R105W. I I not for publication city, town Ralianca I I vicinity state Wyoming code county Sweetwater code zip code 82943 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property dH private US building(s) Contributing Noncontributing [x] public-local -f~~) district ____ _____ buildings [~1 public-State CUsite ____ Y sites dH public-Federal [ I structure ____ ____structures [ I object ____ ____ objects ____ ____Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously listed in the National Register _______ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this El nomination C_3 request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Pjaces and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Appendix A: Study Route Descriptions and Historical Overviews

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR REVISED FEASIBILITY AND SUITABILITY STUDY FOR ADDITIONAL ROUTES OF THE OREGON, MORMON PIONEER, CALIFORNIA, AND PONY EXPRESS NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAILS: APPENDIX A: STUDY ROUTE DESCRIPTIONS AND HISTORICAL OVERVIEWS SEPTEMBER 2017 Cover: “Westport Landing,” watercolor, William Henry Jackson, SCBL_280, Scotts Bluff National Monument, NPS REVISED FEASIBILITY AND SUITABILITY STUDY FOR ADDITIONAL ROUTES OF THE OREGON, MORMON PIONEER, CALIFORNIA, AND PONY EXPRESS NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAILS APPENDIX A: STUDY ROUTE DESCRIPTIONS AND HISTORICAL OVERVIEWS National Park Service 2017 Table of Contents APPENDIX A: STUDY ROUTES AND HISTORICAL SUMMARIES ...................................................................... 1 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................ 1 STUDY ROUTE DESCRIPTIONS ................................................................................................................... 1 HISTORICAL SUMMARIES AND USE ANALYSES ......................................................................................... 2 THE STUDY ROUTES .................................................................................................................................. 6 1. Blue Mills-Independence Road (also called Lower Independence Landing Road) ........................... 6 2. Kansas and Missouri Alternates: Mississippi Saints Route from Independence, Missouri, to Fort Laramie, Wyoming -

Exhibit RMP___(CAT-2.2) - Surrounding Site Information

Exhibit RMP___(CAT-2.2) - Surrounding Site Information A brief description of Jim Bridger plant surrounding scenic, historical, archeological and recreational locations; natural resources; plant and animal life; land reclamation; possible safety hazards; and plans for protecting the environment follows: 1. Historical Sites - National Historic Trails The Cherokee, Overland, Oregon, California, Mormon Pioneer, and Pony Express National Historic Trails cross Sweetwater County, Wyoming in an east-to-west direction. The Point of Rocks to South Pass Stage and Freight Trail crosses Sweetwater County in a south-to-north direction. This trail is located closest to the general vicinity of the plant. All the other trails would be intersected many miles from the plant. A brief description of the referenced trails follows: Cherokee Trails (1849-1850) - Several emigrant parties, including Cherokee Nation Native Americans, journeyed to California along these two trails in the first two years of the gold rush. Starting in western Arkansas and eastern Oklahoma, these emigrant parties blazed these trails as the first wagon trails through the Rocky Mountains that were not routed through South Pass, Wyoming. The 1849 wagon trains traversed a route across the Laramie Plains and the Red Desert that closely parallels the route of present-day Interstate 80, and connects with the Oregon and California trails at the confluence of the Hams Fork and Blacks Fork rivers. In 1850, these emigrant parties pioneered a different route that is near the Wyoming- Colorado border until reaching Fort Bridger. Some combinations of both trails were used to create Ben Holladay's Overland Trail in 1862. The Cherokee Trails are not well marked. -

Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan, Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge

Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge DRAFT COMPREHENSIVE CONSERVATION PLAN and ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT September 2001 Prepared by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge P.O. Box 700 Green River, Wyoming 82935 and Division of Refuge Planning Region 6, Mountain-Prairie Region P.O. Box 25486, DFC Denver, Colorado 80225 Table of Contents Summary .......................................................................................1 I. Introduction / Background 1.1 Refuge Overview: History of Refuge Establishment, Acquisition and Management 1.1.1 Seedskadee NWR Overview ..........................................................4 1.1.2 History of Seedskadee NWR Establishment, Acquisition, and Management ..................4 1.2 Purpose of and Need for Comprehensive Conservation Plan ......................................9 1.3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Mission ........................................................10 1.4 National Wildlife Refuge System Mission, Goals, and Guiding Principles ...........................10 1.5 Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge Purpose(s) ...............................................12 1.6 Seedskadee National Wildlife Refuge Vision Statement .........................................12 1.7 Legal and Policy Guidance ..................................................................13 1.8 Existing Partnerships ......................................................................15 1.9 Potential for Refuge Expansion ..............................................................16 -

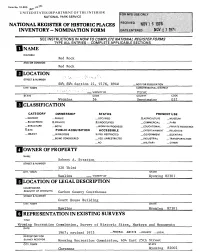

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Red Rock AND/OR COMMON Red Rock LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Section 21, T17N, R94W —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT VICINITY OF First STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Wyoming 56 Sweetwater 037 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED X.AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) 2LPRIVATE X.UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE 2LSITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS 2LYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Robert A. Stratton STREET & NUMBER 520 Third CITY, TOWN STATE Rawlins VICINITY OF Wyoming 82301 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Carbon County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER Court House Building CITY, TOWN STATE Rawlins Wyoming 82301 I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Wyoming Recreation Commission, Survey of Historic Sites, Markers and Monuments DATE 1967; revised 1973 —FEDERAL JXSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Wyoming Recreation Commission, 604 East 25th Street CITY, TOWN STATE Chevenne Wyoming 82002 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT X.DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2LORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS 2LALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED ——————————DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Red Rock is located in south central Wyoming, near the eastern Sweetwater County line, and about 50 miles southwest of the city of Rawlins. At an altitude of 6750 feet above sea level, it is within an area that, sur prisingly to some, is called a basin.