The Endurance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explorer's Gazette

EEXXPPLLOORREERR’’SS GGAAZZEETTTTEE Published Quarterly in Pensacola, Florida USA for the Old Antarctic Explorers Association Uniting All OAEs in Perpetuating the Memory of United States Involvement in Antarctica Volume 18, Issue 4 Old Antarctic Explorers Association, Inc Oct-Dec 2018 Photo by Jack Green The first C-17 of the summer season delivers researchers and support staff to McMurdo Station after a two-week weather delay. Science Bouncing Back From A Delayed Start By Mike Lucibella The first flights from Christchurch to McMurdo were he first planes of the 2018-2019 Summer Season originally scheduled for 1 October, but throughout early Ttouched down at McMurdo Station’s Phoenix October, a series of low-pressure systems parked over the Airfield at 3 pm in the afternoon on 16 October after region and brought days of bad weather, blowing snow more than two weeks of weather delays, the longest and poor visibility. postponement of season-opening in recent memory. Jessie L. Crain, the Antarctic research support Delays of up to a few days are common for manager in the Office of Polar Programs at the National researchers and support staff flying to McMurdo Station, Science Foundation (NSF), said that it is too soon yet to Antarctica from Christchurch, New Zealand. However, a say definitively what the effects of the delay will be on fifteen-day flight hiatus is very unusual. the science program. Continued on page 4 E X P L O R E R ‘ S G A Z E T T E V O L U M E 18, I S S U E 4 O C T D E C 2 0 1 8 P R E S I D E N T ’ S C O R N E R Ed Hamblin—OAEA President TO ALL OAEs—I hope you all had a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year holiday. -

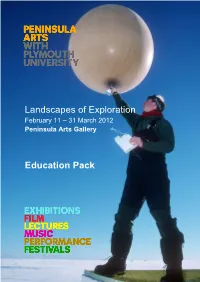

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

Endurance: a Glorious Failure – the Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 by Alasdair Mcgregor

Endurance: A glorious failure – The Imperial Transantarctic Expedition 1914 – 16 By Alasdair McGregor ‘Better a live donkey than a dead lion’ was how Ernest Shackleton justified to his wife Emily the decision to turn back unrewarded from his attempt to reach the South Pole in January 1909. Shackleton and three starving, exhausted companions fell short of the greatest geographical prize of the era by just a hundred and sixty agonising kilometres, yet in defeat came a triumph of sorts. Shackleton’s embrace of failure in exchange for a chance at survival has rightly been viewed as one of the greatest, and wisest, leadership decisions in the history of exploration. Returning to England and a knighthood and fame, Shackleton was widely lauded for his achievement in almost reaching the pole, though to him such adulation only heightened his frustration. In late 1910 news broke that the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen would now vie with Shackleton’s archrival Robert Falcon Scott in the race to be first at the pole. But rather than risk wearing the ill-fitting and forever constricting suit of the also-ran, Sir Ernest Shackleton then upped the ante, and in March 1911 announced in the London press that the crossing of the entire Antarctic continent via the South Pole would thereafter be the ultimate exploratory prize. The following December Amundsen triumphed, and just three months later, Robert Falcon Scott perished; his own glorious failure neatly tailored for an empire on the brink of war and searching for a propaganda hero. The field was now open for Shackleton to hatch a plan, and in December 1913 the grandiloquently titled Imperial Transantarctic Expedition was announced to the world. -

The Bibliofiles: Victoria Mckernan

The BiblioFiles: Victoria McKernan Premiere date: April 28, 2012 DR. DANA: The Cotsen Children's Library at Princeton University Library presents The BiblioFiles. [MUSIC PLAYING] DR. DANA: Hi, this is Dr. Dana. Today my guest is Victoria McKernan, author of Shackleton's Stowaway. In 1914, British explorer Ernest Shackleton and his crew of 27 men set off on a tremendously ambitious expedition. Their goal was to be the first men to cross the Antarctic continent. Unfortunately, their ship, the Endurance, never reached land. Instead, it became trapped by pack ice in the Weddle Sea. The ship was eventually crushed by the ice, forcing the men to travel by lifeboat and land on the barren and inhospitable Elephant Island. Since the island was too remote for passing ships, there was no hope of rescue. So Shackleton and five others returned to sea in a tiny boat and sailed 800 miles to South Georgia Island. There, they hoped to contact a whaling station and return for the others. When hurricane strength winds forced them to land on the wrong side of South Georgia Island, Shackleton and two others trekked 25 miles over mountains-- 36 hours without stopping-- to reach civilization. Eventually, Shackleton rescued the three men on South Georgia Island and the 22 men stranded on Elephant Island. Despite incredible odds and unimaginable hardships, not a single man was lost. The story of Ernest Shackleton is absolutely true, and author Victoria McKernan brings it to life through the eyes of Perce Blackborow, a young sailor who actually stowed away on the Endurance in 1914. -

Tom Crean – Antarctic Explorer

Tom Crean – Antarctic Explorer Mount Robert Falcon Scott compass The South Pole Inn Terra Nova Fram Amundsen camp Royal Navy Weddell Endurance coast-to-coast Annascaul food Elephant Georgia glacier Ringarooma experiments scurvy south wrong Tom Crean was born in __________, Co. Kerry in 1877. When he was 15 he joined the_____ _____. While serving aboard the __________ in New Zealand, he volunteered for the Discovery expedition to the Antarctic. The expedition was led by Captain __________ _________ __________. The aim of the expedition was to explore any lands that could be reaching and to conduct scientific __________. Tom Crean was part of the support crew and was promoted to Petty Officer, First Class for all his hard work. Captain Scott did not reach the South Pole on this occasion but he did achieve a new record of furthest __________. Tom Crean was asked to go on Captain Scott’s second expedition called __________ __________to Antarctica. This time Captain Scott wanted to be the first to reach the South Pole. There was also a Norwegian expedition called __________ led by Roald __________ who wanted to be the first to reach the South Pole. Tom Crean was chosen as part of an eight man team to go to the South Pole. With 250km to go to the South Pole, Captain Scott narrowed his team down to five men and ordered Tom Crean, Lieutenant Evans and Lashly to return to base _______. Captain Scott made it to the South Pole but were beaten to it by Amundsen. They died on the return journey to base camp. -

Navigation on Shackleton's Voyage to Antarctica

Records of the Canterbury Museum, 2019 Vol. 33: 5–22 © Canterbury Museum 2019 5 Navigation on Shackleton’s voyage to Antarctica Lars Bergman1 and Robin G Stuart2 1Saltsjöbaden, Sweden 2Valhalla, New York, USA Email: [email protected] On 19 January 1915, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, under the leadership of Sir Ernest Shackleton, became trapped in their vessel Endurance in the ice pack of the Weddell Sea. The subsequent ordeal and efforts that lead to the successful rescue of all expedition members are the stuff of legend and have been extensively discussed elsewhere. Prior to that time, however, the voyage had proceeded relatively uneventfully and was dutifully recorded in Captain Frank Worsley’s log and work book. This provides a window into the navigational methods used in the day-to- day running of the ship by a master mariner under normal circumstances in the early twentieth century. The conclusions that can be gleaned from a careful inspection of the log book over this period are described here. Keywords: celestial navigation, dead reckoning, double altitudes, Ernest Shackleton, Frank Worsley, Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition, Mercator sailing, time sight Introduction On 8 August 1914, the Imperial Trans-Antarctic passage in the 22½ foot (6.9 m) James Caird to Expedition under the leadership of Sir Ernest seek rescue from South Georgia. It is ultimately Shackleton set sail aboard their vessel the steam a tribute to Shackleton’s leadership and Worsley’s yacht (S.Y.) Endurance from Plymouth, England, navigational skills that all survived their ordeal. with the goal of traversing the Antarctic Captain Frank Worsley’s original log books continent from the Weddell to Ross Seas. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

The polar sublime in contemporary poetry of Arctic and Antarctic exploration. JACKSON, Andrew Buchanan. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20170/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20170/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. jj Learning and information Services I Adsetts Centre, City Campus * Sheffield S1 1WD 102 156 549 0 REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10700005 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10700005 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 The Polar Sublime in Contemporary Poetry of Arctic and Antarctic Exploration Andrew Buchanan Jackson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2015 Abstract In this thesis I formulate the concept of a polar sublime, building on the work of Chauncy Loomis and Francis Spufford, and use this new framework for the appraisal of contemporary polar-themed poetry. -

After Editing

Shackleton Dates AUGUST 8th 1914 The team leave the UK on the ship, Endurance. DEC 5th 1914 They arrive at the edge of the Antarctic pack ice, in the Weddell Sea. JAN 18th 1915 Endurance becomes frozen in the pack ice. OCT 27TH 1915 Endurance is crushed in the ice after drifting for 9 months. Ship is abandoned and crew start to live on the pack ice. NOV 1915 Endurance sinks; men start to set up a camp on the ice. DEC 1915 The pack ice drifts slowly north; Patience camp is set up. MARCH 23rd 2016 They see land for the first time – 139 days have passed; the land can’t be reached though. APRIL 9th 2016 The pack ice starts to crack so the crew take to the lifeboats. APRIL 15th 1916 The 3 crews arrive on ELEPHANT ISLAND where they set up camp. APRIL 24th 1916 5 members of the team, including Shackleton, leave in the lifeboat James Caird, on an 800 mile journey to South Georgia, for help. MAY 10TH 1916 The James Caird crew arrive in the south of South Georgia. MAY 19TH -20TH Shackleton, Crean and Worsley walk across South Georgis to the whaling station at Stromness. MAY 23RD 1916 All the men on Elephant Island are safe; Shackleton starts on his first attempt at a rescue from South Georgia but ice prevents him. AUGUST 25th Shackleton leaves on his 4th attempt, on the Chilian tug boat Yelcho; he arrives on Elephant Island on August 30th and rescues all his crew. MAY 1917 All return to England. -

Antarctica: Music, Sounds and Cultural Connections

Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Antarctica Music, sounds and cultural connections Edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson and Arnan Wiesel Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections / edited by Bernadette Hince, Rupert Summerson, Arnan Wiesel. ISBN: 9781925022285 (paperback) 9781925022292 (ebook) Subjects: Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)--Centennial celebrations, etc. Music festivals--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. Antarctica--Discovery and exploration--Australian--Congresses. Antarctica--Songs and music--Congresses. Other Creators/Contributors: Hince, B. (Bernadette), editor. Summerson, Rupert, editor. Wiesel, Arnan, editor. Australian National University School of Music. Antarctica - music, sounds and cultural connections (2011 : Australian National University). Dewey Number: 780.789471 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photo: Moonrise over Fram Bank, Antarctica. Photographer: Steve Nicol © Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents Preface: Music and Antarctica . ix Arnan Wiesel Introduction: Listening to Antarctica . 1 Tom Griffiths Mawson’s musings and Morse code: Antarctic silence at the end of the ‘Heroic Era’, and how it was lost . 15 Mark Pharaoh Thulia: a Tale of the Antarctic (1843): The earliest Antarctic poem and its musical setting . 23 Elizabeth Truswell Nankyoku no kyoku: The cultural life of the Shirase Antarctic Expedition 1910–12 . -

THE PUBLICATION of the NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No

THE PUBLICATION OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 34, No. Vol 03 9 770003 532006 Vol 34, No. 3, 2016 Issue 237 Contents www.antarctic.org.nz is published quarterly by the New Zealand Antarctic Society Inc. ISSN 0003-5327 30 The New Zealand Antarctic Society is a Registered Charity CC27118 EDITOR: Lester Chaplow ASSISTANT EDITOR: Janet Bray New Zealand Antarctic Society PO Box 404, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand Email: [email protected] INDEXER: Mike Wing The deadlines for submissions to future issues are 1 November, 1 February, 1 May and 1 August. News 25 Shackleton’s Bad Lads 26 PATRON OF THE NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY: From Gateway City to Volunteer Duty at Scott Base 30 Professor Peter Barrett, 2008 NEW ZEALAND ANTARCTIC SOCIETY How You Can Help Us Save Sir Ed’s Antarctic Legacy 33 LIFE MEMBERS The Society recognises with life membership, First at Arrival Heights 34 those people who excel in furthering the aims and objectives of the Society or who have given outstanding service in Antarctica. They are Conservation Trophy 2016 36 elected by vote at the Annual General Meeting. The number of life members can be no more Auckland Branch Midwinter Celebration 37 than 15 at any one time. Current Life Members by the year elected: Wellington Branch – 2016 Midwinter Event 37 1. Jim Lowery (Wellington), 1982 2. Robin Ormerod (Wellington), 1996 3. Baden Norris (Canterbury), 2003 Travelling with the Huskies Through 4. Bill Cranfield (Canterbury), 2003 the Transantarctic Mountains 38 5. Randal Heke (Wellington), 2003 6. Bill Hopper (Wellington), 2004 Hillary’s TAE/IGY Hut: Calling all stories 40 7. -

JOURNAL Number Six

THE JAMES CAIRD SOCIETY JOURNAL Number Six Antarctic Exploration Sir Ernest Shackleton MARCH 2012 1 Shackleton and a friend (Oliver Locker Lampson) in Cromer, c.1910. Image courtesy of Cromer Museum. 2 The James Caird Society Journal – Number Six March 2012 The Centennial season has arrived. Having celebrated Shackleton’s British Antarctic (Nimrod) Expedition, courtesy of the ‘Matrix Shackleton Centenary Expedition’, in 2008/9, we now turn our attention to the events of 1910/12. This was a period when 3 very extraordinary and ambitious men (Amundsen, Scott and Mawson) headed south, to a mixture of acclaim and tragedy. A little later (in 2014) we will be celebrating Sir Ernest’s ‘crowning glory’ –the Centenary of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic (Endurance) Expedition 1914/17. Shackleton failed in his main objective (to be the first to cross from one side of Antarctica to the other). He even failed to commence his land journey from the Weddell Sea coast to Ross Island. However, the rescue of his entire team from the ice and extreme cold (made possible by the remarkable voyage of the James Caird and the first crossing of South Georgia’s interior) was a remarkable feat and is the reason why most of us revere our polar hero and choose to be members of this Society. For all the alleged shenanigans between Scott and Shackleton, it would be a travesty if ‘Number Six’ failed to honour Captain Scott’s remarkable achievements - in particular, the important geographical and scientific work carried out on the Discovery and Terra Nova expeditions (1901-3 and 1910-12 respectively). -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. Special thanks goes to Moe Liu- D'Albero, Director of Budget and Operations for the Division of the Humanities and the Arts, who worked the bureaucratic college award system to get the funds to me in time.