Suman Paul, Kanan Chatterjee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Population Growth in the Municipalities of North 24 Parganas, It Is Clear That North 24 Parganas Has Retained a High Level of Urbanization Since Independence

World Wide Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Development WWJMRD 2018; 4(3): 68-73 www.wwjmrd.com International Journal Peer Reviewed Journal Urban Population Growth in the Municipalities of Refereed Journal Indexed Journal North 24 Parganas: A Spatio-Temporal Analysis UGC Approved Journal Impact Factor MJIF: 4.25 E-ISSN: 2454-6615 Mashihur Rahaman Mashihur Rahaman Abstract Research Scholar The rapid growth of urban population causes various problems in urban centres like increased P.G. Department of unemployment, economic instability, lacks of urban facilities, unhygienic environmental conditions Geography, Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar, etc. People were well aware about the importance of population studies from very beginning. Odisha, India Explosively growing of urban population has attracted the attention of urban geographers and town planners. For country like India, it is very important to study the decadal variation of population growth, it helps in realizing problems. The population growth and socio-economic changes are closely related to each other. In present study North 24 Parana’s has been chosen as study area. The level of urbanization remained high in the district (57.6 % in 2011). Rapid increase in urbanization can be attributed to growth of Kolkata metropolis.Barasat is now within greater Kolkata (Kolkata 124).From 1991 onwards the real estate business in this district thrived and projects were taken which are more of residential type than business type. The aim of the present paper is to investigate the change in urban population growth rate of municipality wise during the three decades 1981-91, 1991- 2001 and 2001-2011. Due to push-pull factors the rural-urban migration is causing the process of urbanization. -

Page 1 of 8 LIST of CLINICAL ESTABLISHMENT (DIAGNOSTIC CENTRE), BARASAT SUB. DIV. NORTH 24 PARGANAS

Page 1 of 8 LIST OF CLINICAL ESTABLISHMENT (DIAGNOSTIC CENTRE), BARASAT SUB. DIV. NORTH 24 PARGANAS Last Sl Owner Facilities Name of Doctors Licence Revenue Name Address Phone No. Owners Name renewed No. Ph. No. Available on roll No. Collected upto Hospital Road, Sarkar X-Ray Clinic & Patho Lab Dr Debasish 1 Habra, North 24 253524 Sashim Sarkar, 5/56N 9.2.2008 Rs 1500 Clical Laboratory, Medium Majumder Parganas Patapatti, Kalibari, Eastern Clinical Patho Lab, 2 Habra, North 24 03216233212 Dr. R. Debnath 03216270412 Dr Ranjit Kr Debnath 12/71N 25.10.2005 Rs 500 Laboratory Medium Parganas Jessore Road, Champadali, Patho Lab 3 Gan Labarotary, 25622479 Ashim Gan 25622479 Dr K Chatterjee 36/25N 20.8.2005 Rs 500 Barasat, North 24 Medium Parganas Diagnostic Nabapally Colony Patho Lab Dr Manish 4 Laboratory & Chest More, Barasat, North 25524117 Aloka Mukherjee 25524117 115/23N 24.2.2006 Rs 250 Small Mukherjee Clinic, 24 Parganas 6, K.N.C. Raod, 1St Floor, Haritala, Dr. Ramesh Ch. 5 Health Care Centre, 25424479 25424479 Patho Lab DR G Mukherjee 101/N/130/P 16.5.2005 Rs 1750 Barasat, North 24 Saha, Parganas Barasat Cancer Banamapipur, Secretary Barasat Patho Lab 6 Research & Welfare Barasat, North 24 25622500 Cancer Research & 25522222 Dr Samir Roy 200/215/N 2.1.2006 Rs 1000 Medium Centre, Parganas Welfare Centre Chowmatha Badu Reliance Clinical Road, Patho Lab 7 25388155 Shiv Sankar Saha 25731834 Dr S R Chowdhury 249N/234 17.6.2005 Rs 500 Laboratory Madhyamgram, Small North 24 Parganas Bidhan Park, Dr A K Roy 8 Life Line Laboratory, Barasat, North 24 25521857 Chitali Mukherjee 25521930 Patho Small 258/273N 16.2.2006 Rs 375 Chowdhury Pargans Gobardanga Station Re-Life Diagonstic Patho Lab Dr A K Roy 9 Road, North 24 03216249885 Kalyan Samaddar 02316248569 299N/284 15.11.2005 Rs 500 Laboratory, Small Chowdhury Parganas Dolphin Medical 650/A/1 Ashoknagar, 03 Patho Lab Dr Kumud Ranjan 10 Smt. -

An Appraisal of Women Empowerment: a Case Study in Jetia Gram Panchayat of Barrackpore Block-I, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal

IOSR Journal of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 11, Series 1 (November. 2020) 25-34 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org An appraisal of Women Empowerment: A Case study in Jetia Gram Panchayat of Barrackpore Block-I, North 24 Parganas, West Bengal. Dr Rimi Roy Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Vivekananda College, Madhyamgram, North 24 Parganas, India. Abstract: Background: In rural areas of India, women have engaged themselves in different jobs to maintain their families and raise their standard of living (Motkuri & Naik, Growth and structure of workforce in India: an analysis of census data, 2016). But they face many problems in their work place that acts as an obstacle and prevent the women to exhibit their working skill in spite of having the same potential as that of men and thus obstacles rise in the path of achieving women empowerment. An attempt has been made in this paper to analyze the present scenario of working women in five villages in Barrackpore Block-I of North 24 Parganas, to highlight the obstacles that are hindering the women empowerment and to suggest suitable recommendations. This paper will help the policy makers to undertake policies regarding rural women empowerment to remove the problems and lead to move involvement of women in working sector. Materials and Methods: Both primary and secondary data were collected for the completion of the study. Primary data were collected by household survey by visiting and interviewing the respondents of the five villages. Secondary data were collected from the District Census Hand Book, Primary census abstract of 1991-2011, Gram Panchayat office, BDO office, Journals, Articles and the details on various schemes were collected from Government websites for data analysis and literature review. -

Ist Cover Page-I-Ii.P65

DISTRICT HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT NORTH 24 PARGANAS DEVELOPMENT & PLANNING DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL District Human Development Report: North 24 Parganas © Development and Planning Department Government of West Bengal First Published February, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission from the Publisher. Front Cover Photograph: Women of SGSY group at work. Back Cover Photograph: Royal Bengal Tiger of the Sunderban. Published by : HDRCC Development & Planning Department Government of West Bengal Setting and Design By: Saraswaty Press Ltd. (Government of West Bengal Enterprise) 11 B.T. Road, Kolkata 700056 Printed by: Saraswaty Press Ltd. (Government of West Bengal Enterprise) 11 B.T. Road, Kolkata 700056 While every care has been taken to reproduce the accurate date, oversights/errors may occur. If found, please convey it to the Development and Planning Department, Government of West Bengal. Minister-in-Charge Department of Commerce & Industries, Industrial Reconstruction, Public Enterprises and Development & Planning GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL E-mail : [email protected] Foreword It has been generally accepted since ancient times that welfare and well being of human is the ultimate goal of Human Development. An environment has to be created so that the people, who are at the centre of the churning process, are able to lead healthy and creative lives. With the publication of the West Bengal Human Development Report in 2004 and it being subsequently awarded by the UNDP for its dispassionate quality of analysis and richness in contents, we had to strive really hard to prepare the District Human Development Reports. -

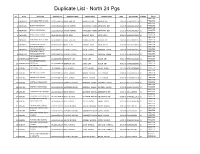

Duplicate List - North 24 Pgs

Duplicate List - North 24 Pgs Sl Block Institution Applicant ID Applicant Name Father Name Mother Name DOB Account NO Scheme Status SANCTION 1 AMDANGA AMDANGA HIGH SCHOOL 19110109903130000479SAIDA KHATUN SAHIDUL ISLAM NASIMA BIBI 13-05-01 0355010181426 K1 FINALIZED SANCTION 2 AMDANGA BODAI HIGH SCHOOL 19110105102140000017SALMA KHATUN SAMSUDDIN MONDALSAHANARA BIBI 17-12-99 412610510000549K1 FINALIZED SANCTION 3 AMDANGA BODAI HIGH SCHOOL 19110105102150000009SALMA KHATUN SAMSUDDIN MONDALSAHANARA BIBI 17-12-99 427810510001720K1 FINALIZED SANCTION 4 AMDANGA BODAI HIGH SCHOOL 19110105102140000157KOYEL BERA BISWAJIT BERA MITALI BERA 26-04-01 412610510002356K1 FINALIZED SANCTION 5 AMDANGA AMDANGA HIGH SCHOOL 19110109903150000007SAIDA KHATUN SAHIDUL ISLAM NASIMA BIBI 13-05-01 0355010181425 K1 FINALIZED SANCTION 6 AMDANGA BODAI HIGH SCHOOL 19110105102130000472KOYEL BERA BISWAJIT BERA MITALI BERA 26-04-01 412610510001618K1 FINALIZED BHAGABATI SMRITI SANCTION 7 AMDANGA VIDYAMANDIR HIGH 19110108401140000057CHAITALI GHOSH GOPAL GHOSH MANDIRA GHOSH 17-03-01 0756010169013 K1 FINALIZED BHAGABATI SMRITI SANCTION 8 AMDANGA VIDYAMANDIR HIGH 19110108401150000029CHAITALI GHOSH GOPAL GHOSH MANDIRA GHOSH 17-03-01 0756010222181 K1 FINALIZED KALYANGARH BALIKA SANCTION 9 ASHOKENAGAR-KALYANGARHVIDYALAYA MUNICIPALITY19112500405130000421BAISHAKHI DEY ASHOK DEY BULON DEY 30-01-00 5549010033442 K1 FINALIZED KALYANGARH BALIKA SANCTION 10 ASHOKENAGAR-KALYANGARHVIDYALAYA MUNICIPALITY19112500405140000042BAISHAKHI DEY ASHOK DEY BULON DEY 30-01-00 5549010035635 K1 FINALIZED -

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr. -

Rainfall, North 24-Parganas

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2016 - 17 NORTHNORTH 2424 PARGANASPARGANAS,, BARASATBARASAT MAP OF NORTH 24 PARGANAS DISTRICT DISASTER VULNERABILITY MAPS PUBLISHED BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHOWING VULNERABILITY OF NORTH 24 PGS. DISTRICT TO NATURAL DISASTERS CONTENTS Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1. Foreword 2. Introduction & Objectives 3. District Profile 4. Disaster History of the District 5. Disaster vulnerability of the District 6. Why Disaster Management Plan 7. Control Room 8. Early Warnings 9. Rainfall 10. Communication Plan 11. Communication Plan at G.P. Level 12. Awareness 13. Mock Drill 14. Relief Godown 15. Flood Shelter 16. List of Flood Shelter 17. Cyclone Shelter (MPCS) 18. List of Helipad 19. List of Divers 20. List of Ambulance 21. List of Mechanized Boat 22. List of Saw Mill 23. Disaster Event-2015 24. Disaster Management Plan-Health Dept. 25. Disaster Management Plan-Food & Supply 26. Disaster Management Plan-ARD 27. Disaster Management Plan-Agriculture 28. Disaster Management Plan-Horticulture 29. Disaster Management Plan-PHE 30. Disaster Management Plan-Fisheries 31. Disaster Management Plan-Forest 32. Disaster Management Plan-W.B.S.E.D.C.L 33. Disaster Management Plan-Bidyadhari Drainage 34. Disaster Management Plan-Basirhat Irrigation FOREWORD The district, North 24-parganas, has been divided geographically into three parts, e.g. (a) vast reverine belt in the Southern part of Basirhat Sub-Divn. (Sundarban area), (b) the industrial belt of Barrackpore Sub-Division and (c) vast cultivating plain land in the Bongaon Sub-division and adjoining part of Barrackpore, Barasat & Northern part of Basirhat Sub-Divisions The drainage capabilities of the canals, rivers etc. -

I ~ !I'd PEOPLE 0Rifjmd 9 • 2 • 2001 to 5 · 3 · 2001" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> Guideline for Household Enumeration F.Ti,T"~ M"I Cf> I ~ !I'd PEOPLE 0Rifjmd 9 • 2 • 2001 to 5 · 3 · 2001

For oJJidlllllSe only Guideline for Household Enumeration f.ti,t"~ M"I Cf> I ~ !I'd PEOPLE 0RIFJmD 9 • 2 • 2001 to 5 · 3 · 2001 ISSUED BY DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS WEST BENGAL lOB, ABDUL HAMID STREET CALCUTTA - 700 069 Phone No.: (033) 220 • 12271248-85311 210-8220 Fax No. : (033) 220 - 1227 E-mail: [email protected] ~: ~~ T~16frrJm : "STACENSUS" GOVERNMENT OF INDIA "'!'~ MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS/GRIHA MANTRALAYA ~. \iR1TUAI ~. ~ tf1m;j OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, WEST BENGAL 20B, ABDUL HAMID STREET, CALCUTTA-700 069 fl./No ......... p.~.Q.. (p.).!..qr.!..~Q99J I / 1217 (36) ~lDated ........ L7.• Q7.1.0'O'O ........ To The District Magistrate & Principal Census Officer, Commissioner & Principal Census Officer, Calcutta Municipal Corporation I Howrah Municipal Corporation. Sub: Detailed guideline on Household or population Enumeration 200 I. Ref: Guideline No. 12 Sir, I am enclosing a detailed guideline for Population Enumeration in 2001 for your perusal and follow up action. It is requested that the copies of the guideline may kindly be circulated to all the Census Officers, Charge Officers as per distribution list given below. 1. Office of the District Magistrate 4 Copies. including Additional Principal Census Officer & District Census Officer. 2. Assistant Director of Statistics & I Copy. Additional District Census Officer. 3. Sub Divisionl Officer and Sub 2 copies. Divisional Principal Censu,s Officer. 4. Block Development Officer & 4 copies. Block Charge Officer. 5. Chairman & Town Charge Officer. 4 copies. 6. Charge officer for Special Area. 2 copies. Yours faithf\:lY, Enclo .•... no. of copies as stated. ~. \-:r\1'11~ (VIKRAM SEN ) Director· Census Operations, West Bengal ii iii INDEX SL. -

North 24 Parganas Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.1/70 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL N0063,RAJENDRAPU MANDRA HAZERALI R,MATIA , NORTH NORTH 24 MANDRA HAZERALI SMRITI VIDYAPITH, NORTH 24 1 123204806129 AARYAN IQBAL 19111006005 M GENERAL NONE 73 53 126 TWENTY FOUR PARGANAS SMRITI VIDYAPITH VILL+P.O.-MANDRA, PARGANAS PARGANAS 743291 24PGS(N), PIN-743438 GOURANGA GOVT_BARASAT NAGAR,GOURANGA P.C.S. GOVT. HIGH ABHISHEK NAGAR,NEWTOWN , NORTH 24 GOVT_BARASAT P.C.S. SCHOOL, KNC ROAD, NORTH 24 2 123204804118 19112300415 M SC NONE 47 54 101 MANDAL NORTH TWENTY PARGANAS GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL P.O. BARASAT, DIST PARGANAS FOUR PARGANAS NORTH 24 PARGANAS, 700159 PIN-700124 THAKURNAGAR,THA THAKURNAGAR HIGH KURNAGAR,GAIGHA SCHOOL, VILL+PO- NORTH 24 THAKURNAGAR HIGH NORTH 24 3 123204808089 ABHRA SARKAR TA , NORTH 19112206602 THAKURNAGAR, M SC NONE 61 39 100 PARGANAS SCHOOL PARGANAS TWENTY FOUR NORTH 24 PGS, PIN- PARGANAS 743287 743287 SHIMULIAPARA,CHA NDPARA CHANDPARA BALIKA BAZAR,GAIGHATA , NORTH 24 CHANDPARA BALIKA NORTH 24 4 123204808080 ADRITA ROY 19112209801 VIDYALAYA, , PIN- F SC NONE 63 57 120 NORTH TWENTY PARGANAS VIDYALAYA PARGANAS 743245 FOUR PARGANAS 743245 BASIRHAT RAJBALLAVPUR HIGH ROAD,RAJBALLAVP SCHOOL, VILL- NORTH 24 RAJBALLAVPUR HIGH -

Wt4ltr Deputy Secretar5r (DAS) Phone: O 1 1-2338 1O1, 2Ggststs

F. No.: 41912015- PMU(DASI Ministry of Informatlon and Broadeasting Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi **** Date: 2td November, 2015 hrblic Notice Reference list of urban areas to be covered in phase III of cable TV digitisation, which was issued by the Ministry on 30.4.2015. The updated list of urban areas for 16 States/UTs has been notified vide Rrblic Notice dated 16. 10.2015 Now, based on comments/data received from the State/UT Governments, the list of the following States/UTs has been updated; 1. Andhra Pradesh 2. Chhattisgarh 3. Jammu & Kashmir 4. Kerala 5. Madhya Pradesh 6. Manipur 7. Telengana 8. Daman & Diu 2. A copy of the updated list of these States/UTs is attached. Wt4ltr Deputy Secretar5r (DAS) Phone: O 1 1-2338 1O1, 2ggSTSTs 2ND UPDATED URBAN AREAS LIST FOR PHASE III OF CABLE TV DIGITISATION Andhra Pradesh S.No. Districts Urban Areas TV Households Remarks 1 Srikakulam Srikakulam (M + OG) 28,149 Palasa Kasibugga (M) 9,706 Ichchapuram (M) 6,242 Sompeta (CT) *Deleted Hiramandalam (CT) *Deleted Upgraded Palakonda 3,349 Tekkali (CT) *Deleted Rajam (NP) 7,367 Amadalavalasa (M) 6,844 Narasannapeta (CT) *Deleted Balaga (CT) *Deleted Ponduru (CT) *Deleted 2 Vizianagaram Parvathipuram (M) 9,382 Bobbili (M) 10,337 Salur (M) 8,644 Gajapathinagaram (CT) *Deleted Sriramnagar (CT) *Deleted Cheepurupalle (CT) *Deleted Tummikapalle (CT) *Deleted Kothavalasa (CT) *Deleted Vizianagaram (M + OG) 44,379 Kanapaka (CT) *Deleted Malicherla (CT) *Deleted Jarjapupeta (CT) *Deleted Upgraded Nellimarla 3,402 Chintalavalasa (CT) *Deleted Visakhapatnm All areas except Visakhapatnam 3 Greater Visakhapatnam (M. (MC)covered in Corp) ? Phase II Yelamanchali ? **Added Narsipatnam ? **Added 4 East Godavari Kakinada (M Corp. -

West Bengal Housing Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (A Govt

West Bengal Housing Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (A Govt. of West Bengal Undertaking) „HIDCO BHABAN‟, Premises No. 35-1111, Major Arterial Road, 3rd Rotary, New Town, Kolkata-700156. Telephone No. (033) 2324-6037/38, Fax (033) 2324-3016/6009 e-mail:[email protected] / [email protected] website : www.wbhidcoltd.com No. 344/HIDCO/Plng/152(Z)/2020Date :07.08.2020 Notice inviting Expressions of Interest for conducting a detailed land survey for preparation of a Base Map for demarcation of the boundaries of New Town Police Station, New Town Eco-Park Police Station and Techno City Police Station Expressions of Interest (EOI) are hereby invited from reputed & experienced Firms / Companies / Organizations for conducting a detailed land surveycovering an area of 3000 Acres (approximately) in the following Mouzas for preparation of a Base Map for demarcation of the boundaries of New Town Police Station, New Town Eco-Park Police Station and Techno City Police Station. The areas to be surveyed are outside the New Town Project Area, but within the New Town Planning Area. NAME OF NAME OF J.L. SHEET PORTION PORTION POLICE MOUZA NO. NO. INSIDE NEW OUTSIDE NEW STATION TOWN TOWN PROJECT PROJECT BOUNDARY BOUNDARY CHANDIBERIA 15 - YES YES TARULIA 21 - YES YES MAHISHGOT 20 - YES YES MAHISHBATHAN 18 1 YES - THAKDARI 19 1 YES YES NEW TOWN POLICE THAKDARI 19 2 YES YES STATION SULANGGARI 22 - - YES GHUNI 23 1 - YES GHUNI 23 3 YES YES JATRAGACHHI 24 2 YES YES JATRAGACHHI 24 3 YES YES SULANGGARI 22 - YES YES NEW TOWN GHUNI 23 1 YES YES ECO PARK GHUNI 23 2 YES - POLICE STATION GHUNI 23 3 - YES JATRAGACHHI 24 1 YES YES Page 1 of 6 West Bengal Housing Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (A Govt. -

June, Qhiv.H VT Approved by the Secretary (SE&Am

FiIeNo.l-6/2020-IS-ll Government of India Ministry of Human Resource Development Department of School Education & Literacy Dated: OS'^'Aug, 2020 Subject; Minutes of the meeting of the Project Approval Board held on 16'" June, 2020 through Video Conference to consider the Annual Work Plan & Budget (AWP&B)2020-21 of Samagra Shiksha for the State of West Bengal. X. u A ^ Approval Board (PAB)for considering tlie Annual Work Plan under^ theP Chaumanship^ 2020-21 of Secretary, under SE&L Samagra on 16.06.2020Shiksha for through the State Video of West Conferen^g. Bengal was held ShikshaqhiV.h VT for the State of West Bengal isapproved enclosed. by the Secretary (SE&L), in respect of Samagra Enclosure: As stated above. (Rusjhi-MaH^^an) Under Secretary to the Govt. India Tel No.: 011-23385459 Email ID: [email protected] To, 1. Secretary, Ministry of Women & Child Development. 2. Secretary, Ministry of Labour & Employment. 3. Secretary, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment 4. Secretary, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. 5. Secretary, Ministry of Jal Shakti. 6. Secretary, Ministry of Minority Affairs. 7. Dy. Adviser (School Education), Niti Aayog 8. Director, NCERT. 9. Vice Chancellor, NIEPA. 10. Chairperson, NCTE 11. Vice Chancellor, IGNOU 12. Member Secretary, NCPCR 13. Joint Secretary (Inst.), MHRD,New Delhi 14. JS(MDM), MHRD,New Delhi 15. JS(SS-I),MHRD 16. JS & FA, MHRD,New Delhi 17. DDG(Stats.), MHRD,New Delhi 18. Principal Secretary (Education), State of West Bengal ' 19. Director (School Education) and State Project Director, Samagra Shiksha, State of West Bengal 20.