SMA Reach-Back

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

Squaring the Circles in Syria's North East

Squaring the Circles in Syria’s North East Middle East Report N°204 | 31 July 2019 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 149 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Search for Middle Ground ......................................................................................... 3 A. The U.S.: Caught between Turkey and the YPG ........................................................ 3 1. Turkey: The alienated ally .................................................................................... 4 2. “Safe zone” or dead end? The buffer debate ........................................................ 8 B. Moscow’s Missed Opportunity? ................................................................................. 11 C. The YPG and Damascus: Playing for Time ................................................................ 13 III. A War of Attrition with ISIS Remnants ........................................................................... 16 A. The SDF’s Approach to ISIS Detainees ..................................................................... 16 B. Deteriorating Relations between the SDF and Local Tribes .................................... -

A Blood-Soaked Olive: What Is the Situation in Afrin Today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23

www.theregion.org A blood-soaked olive: what is the situation in Afrin today? by Anthony Avice Du Buisson - 06/10/2018 01:23 Afrin Canton in Syria’s northwest was once a haven for thousands of people fleeing the country’s civil war. Consisting of beautiful fields of olive trees scattered across the region from Rajo to Jindires, locals harvested the land and made a living on its rich soil. This changed when the region came under Turkish occupation this year. Operation Olive Branch: Under the governance of the Afrin Council – a part of the ‘Democratic Federation of Northern Syria’ (DFNS) – the region was relatively stable. The council’s members consisted of locally elected officials from a variety of backgrounds, such as Kurdish official Aldar Xelil who formerly co-headed the Movement for a Democratic Society (TEVDEM) – a political coalition of parties governing Northern Syria. Children studied in their mother tongue— Kurdish, Arabic, or Syriac— in a country where the Ba’athists once banned Kurdish education. The local Self-Defence Forces (HXP) worked in conjunction with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) to keep the area secure from existential threats such as Turkish Security forces (TSK) and Free Syrian Army (FSA) attacks. This arrangement continued until early 2018, when Turkey unleashed a full-scale military operation called ‘ Operation Olive Branch’ to oust TEVDEM from Afrin. The Turkish government views TEVDEM and its leading party, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – listed as a terrorist organisation in Turkey. Under the pretext of defending its borders from terrorism, the Turkish government sent thousands of troops into Afrin with the assistance of forces from its allies in Idlib and its occupied Euphrates Shield territories. -

Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

CARNEGIE COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Studiojumpee / Shutterstock .com TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 Page 12 Page 24 Mission and Purpose Education Section Carnegie New Leaders Page 2 Page 14 Page 25 Letter from Stephen D. Calendar of Events, Podcasts, Global Ethics Fellows Hibbard, Vice Chairman of the and Interviews Board of Trustees Page 26 Page 20 Ethics Fellows for the Future Page 4 Financial Summary Letter to 2114 from Joel H. Page 28 Rosenthal, Carnegie Council Page 21 Officers, Trustees, and President A Special Thank You to our Committees Supporters Page 6 Page 29 Highlights Page 22 Staff List 2014 –2015 Contributors TEXT EDITOR: MADELEINE LYNN DESIGN: DENNIS DOYLE PHOTOGRAPHY: GUSTA JOHNSON PRODUCTION: DEBORAH CARROLL MISSION AND PURPOSE Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs works to foster a global conversation on ethics, faith, and politics that bridges cultures, ethnicities, and religions. Broadcasting across a spectrum of media channels, Carnegie Council brings this conversation directly to the people through their smartphones, tablets, laptops, televisions, and earbuds. WE CONVENE: The world’s leading thinkers in conversations about global issues WE COMMUNICATE: The best ideas in ethics to a global audience. WE CONNECT: Different communities through exploring shared values. Carnegie Council: Making Ethics Matter 1 LETTER FROM STEPHEN D. HIBBARD, VICE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dear Friends, This past year, with the glow of the wonderful two-year celebration of the 100th Anniversary of its founding still lingering, the Carnegie Council energetically began its second century of work. The Council’s longevity is remarkable in itself since institutions, like nations, rise and fall. -

Avrasya Incelemeleri Merkezi Center for Eurasian Studies

AVRASYA İNCELEMELERİ MERKEZİ CENTER FOR EURASIAN STUDIES U.S.-BACKED SYRIA FORCE CLOSES IN ON IS-HELD CITY; SLOW IRAQ ADVANCE CAUSES RIFT - 07.06.2016 Reuters, 06 June 2016 U.S.-backed Syrian fighters have surrounded the Islamic State-held city of Manbij from three sides as they press a major new offensive against the jihadists near the Turkish border, a spokesman for the fighters said on Monday. But in a sign of the difficulty world powers have faced in building a coalition to take on the self- declared caliphate, the slow pace of a separate assault by the Iraqi army on a militant bastion near Baghdad caused a rift between the Shi'ite-led government and powerful Iranian-backed Shi'ite militia. The simultaneous assaults on Manbij in Syria and Falluja in Iraq, at opposite ends of Islamic State territory, are two of the biggest operations yet against Islamic State in what Washington says is the year it hopes to roll back the caliphate. The Syria Democratic Forces (SDF), including a Kurdish militia and Arab allies that joined it last year, launched the Manbij attack last week to drive Islamic State from its last stretch of the Syrian- Turkish frontier. If successful it could cut the militants' main access route to the outside world, paving the way for an assault on their Syrian capital Raqqa. Last week Iraqi forces also rolled into the southern outskirts of Falluja, an insurgent stronghold 750 km down the Euphrates River from Manbij just an hour's drive from Baghdad. The SDF in Syria are backed by U.S. -

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey's

Two Routes to an Impasse: Understanding Turkey’s Kurdish Policy Ayşegül Aydin Cem Emrence turkey project policy paper Number 10 • December 2016 policy paper Number 10, December 2016 About CUSE The Center on the United States and Europe (CUSE) at Brookings fosters high-level U.S.-Europe- an dialogue on the changes in Europe and the global challenges that affect transatlantic relations. As an integral part of the Foreign Policy Studies Program, the Center offers independent research and recommendations for U.S. and European officials and policymakers, and it convenes seminars and public forums on policy-relevant issues. CUSE’s research program focuses on the transforma- tion of the European Union (EU); strategies for engaging the countries and regions beyond the frontiers of the EU including the Balkans, Caucasus, Russia, Turkey, and Ukraine; and broader European security issues such as the future of NATO and forging common strategies on energy security. The Center also houses specific programs on France, Germany, Italy, and Turkey. About the Turkey Project Given Turkey’s geopolitical, historical and cultural significance, and the high stakes posed by the foreign policy and domestic issues it faces, Brookings launched the Turkey Project in 2004 to foster informed public consideration, high‐level private debate, and policy recommendations focusing on developments in Turkey. In this context, Brookings has collaborated with the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TUSIAD) to institute a U.S.-Turkey Forum at Brookings. The Forum organizes events in the form of conferences, sem- inars and workshops to discuss topics of relevance to U.S.-Turkish and transatlantic relations. -

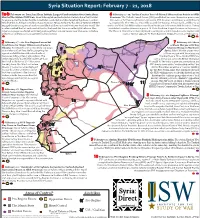

Syria SITREP Map 07

Syria Situation Report: February 7 - 21, 2018 1a-b February 10: Israel and Iran Initiate Largest Confrontation Over Syria Since 6 February 9 - 15: Turkey Creates Two Additional Observation Points in Idlib Start of the Syrian Civil War: Israel intercepted and destroyed an Iranian drone that violated Province: The Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) established two new observation points near its airspace over the Golan Heights. Israel later conducted airstrikes targeting the drone’s control the towns of Tal Tuqan and Surman in Eastern Idlib Province on February 9 and February vehicle at the T4 Airbase in Eastern Homs Province. Syrian Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (SAMS) 15, respectively. The TSK also reportedly scouted the Taftanaz Airbase north of Idlib City as engaged the returning aircraft and successfully shot down an Israeli F-16 over Northern Israel. The well as the Wadi Deif Military Base near Khan Sheikhoun in Southern Idlib Province. Turkey incident marked the first such combat loss for the Israeli Air Force since the 1982 Lebanon War. established a similar observation post at Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 5. Israel in response conducted airstrikes targeting at least a dozen targets near Damascus including The Russian Armed Forces later deployed a contingent of military police to the regime-held at least four military positions operated by Iran in Syria. town of Hadher opposite Al-Eis in Southern Aleppo Province on February 14. 2 February 17 - 20: Pro-Regime Forces Set Qamishli 7 February 18: Ahrar Conditions for Major Offensive in Eastern a-Sham Merges with Key Ghouta: Pro-regime forces intensified a campaign 9 Islamist Group in Northern of airstrikes and artillery shelling targeting the 8 Syria: Salafi-Jihadist group Ahrar opposition-held Eastern Ghouta suburbs of Al-Hasakah a-Sham merged with Islamist group Damascus, killing at least 250 civilians. -

The Syrian Kurdish Movement's Resilience Strategy

Surviving the Aftermath of Islamic State: The Syrian Kurdish Movement’s Resilience Strategy Patrick Haenni and Arthur Quesnay Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 17 February 2020 2020/03 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Patrick Haenni, Arthur Quesnay, 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/03 17 February 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Surviving the Aftermath of Islamic State: The Syrian Kurdish Movement’s Resilience Strategy Patrick Haenni and Arthur Quesnay* * Patrick Haenni is a Doctor of Political Science and Visiting Fellow at the European University Institute (EUI). He is a senior adviser at the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD). Since 2013, his work has focused on the political dynamics in Syrian rebel-held areas. He is the author of two books: Market Islam (Paris, Seuil, 2005) and The Order of the Caïds (Paris, Karthala, 2005). -

1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During The

Weekly Conflict Summary February 1-7, 2018 During the reporting period, the Turkish-led Operation Olive Branch offensive continued its advance into Afrin, the northwestern canton controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a US-backed, Kurdish- led organization). Elsewhere, pro-government forces continued their advance against opposition forces and ISIS fighters in the northern Hama/southern Aleppo countryside, further securing their control in the area. Following a significant uptick in attacks on both the opposition-controlled Idleb and Eastern Ghouta pockets, the UN humanitarian coordinator, Panos Moumtzis, called for an immediate one-month cessation of hostilities for the delivery of humanitarian aid. Lastly, a new opposition “operation room” has been formed in Idleb, with the stated goal of coordinating attacks against government forces. Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by February 7, with arrows indicating fronts of advance during the reporting period 1 of 4 Weekly Conflict Summary – February 1-7, 2018 Operation Olive Branch Operation Olive Branch forces took new territory, connecting previously isolated territories west of Raju and north of Balbal. Turkey-backed Operation Euphrates Shield forces also advanced northwest of A’zaz to take a mountaintop and village from the SDF. No gains have yet been made towards Tal Refaat along the southeastern front. There have been reports of abuses by advancing Turkish-backed, opposition Free Syrian Army (FSA) forces, including footage of Operation Olive Branch forces apparently mutilating the body of a deceased YPJ fighter (an all-female Kurdish unit within the SDF). Hundreds of US-trained YPG/SDF fighters from eastern SDF cantons arrived in Afrin this week, traveling through government-held territory to reinforce the SDF fighters on fronts against Olive Branch units. -

Women Rights in Rojava- English

Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 2 1- Women’s Political Role in the Autonomous Administration Project in Rojava ...................................... 3 1.1 Women’s Role in the Autonomous Administration ....................................................................... 3 1.1.1 Committees for Women ......................................................................................................... 4 1.1.2 The Women’s Committee ....................................................................................................... 4 1.1.3 Women’s Associations - The “Kongreya Star” ........................................................................ 5 1.2 Women’s Representation in Political and Administrative Bodies: ................................................. 6 2. Empowering Women in the Military Field ........................................................................................... 11 2.1 The Representation of Women in the Army ................................................................................ 11 2.2 The People’s Protection Units (YPG) and Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) ................................. 12 2.2.1 The Women’s Protection Units- YPJ ..................................................................................... 12 2.2.2 The People’s Protection Units- YPG ..................................................................................... -

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 31 May - 6 June 2021

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 31 May - 6 June 2021 SYRIA SUMMARY • The predominantly Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) cracks down on anti-conscription protests in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. • The Government of Syria (GoS) offers to defer military service for people wanted in southern Syria. • ISIS assassinates a prominent religious leader in Deir-ez-Zor city. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 6 June 2021. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see footnote 1. Page 1 of 5 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 31 May - 6 June 2021 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 Figure 2: Anti-conscription protests and related events in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate between 31 May – 6 June. Data from The Carter Center and ACLED. Conscription in Northwest Syria In 2019, the Kurdish Autonomous Administration (KAA) issued a controversial conscription law for territories under its control.2 in February, the Syrian Network For Human Rights claimed that the conscription of teachers deprived half a million students of a proper education. 3 People in the region argue that the forcible recruitment and arrests by SDF have disrupted economic life.4 In late May, the SDF escalated its recruitment effort.5 31 May 1 Figure 1 depicts areas of the dominant actors’ control and influence. While “control” is a relative term in a complex, dynamic conflict, territorial control is defined as an entity having power over use of force as well as civil/administrative functions in an area. Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah maintain a presence in Syrian government-controlled territory. Non-state organized armed groups (NSOAG), including the Kurdish-dominated SDF and Turkish-backed opposition groups operate in areas not under GoS control. -

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo, Azaz (as of 1 June 2016) Summary An estimated 16,150 individuals in total have been displaced by fighting since 27 May in the northern Aleppo countryside, with most joining settlements adjacent to the Bab Al Salam border crossing point, Azaz town, Afrin and Yazibag. Kurdish authorities in Afrin Canton have allowed civilians unimpeded access into the canton from roads adjacent to Azaz and Mare’ since 29 May in response to ongoing displacement near hostilities between ISIL and NSAGs. Some 9,000 individuals have been afforded safe passage to leave Mare’ and Sheikh Issa towns after they were trapped by fighting on 27 May; however, an estimated 5,000 civilians remain inside despite close proximity to frontlines. Humanitarian organisations continue to limit staff movement in the Azaz area for safety reasons, and some remain in hibernation. Limited, cautious humanitarian service delivery has started by some in areas of high IDP concentration. The map below illustrates recent conflict lines and the direction of movement of IDPs: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Coordination Saves Lives | www.unocha.org Turkey | Syria: Azaz, Flash Update No.2 Access Overview Despite a recent decline in hostilities since May 27, intermittent clashes continue between NSAGs and ISIL militants on the outskirts of Kafr Kalbien, Kafr Shush, Baraghideh, and Mare’ towns. A number of counter offensives have been coordinated by NSAGs operating in the Azaz sub district, hindering further advancements by ISIL militants towards Azaz town. As of 30 May, following the recent decline in escalations between warring parties, access has increased for civilians wanting to leave Azaz and Mare’ into areas throughout Afrin canton.