To Download a .Pdf Copy of the USVI Preservation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FORT FREDERIK Other Name/Site Nu

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT FREDERIK Page 1 United States Department of tHe Interior, National ParK Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: FORT FREDERIK Other Name/Site Number: Frederiksfort 2. LOCATION Street & Number: South of junction of Mahonany Road and Route 631, Not for publication: N/A North end of Frederiksted City/Town: Frederiksted Vicinity: N/A State: US Virgin Islands County: St. Croix Code: 010 Zip Code: 00840 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): X Public-Local: District: Public-State: X Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 2 buildings 1 sites structures 1 objects 3 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT FREDERIK Page 2 United States Department of tHe Interior, National ParK Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Slave Schools in the Danish West Indies, 1839-1853

/,z/of /1/få off SLAVE SCHOOLS IN THE DANISH WEST INDIES 1839 1853 fx1mfim\firWfiíím'vjfifií|§|í»"mflfi1fln1 The by B rglt Jul Fryd Johansen The Unlv rslty of Copenhagen H tor oal In t tute 1988 IHTRODUCTIOH _ Literature Source material _ _ REFORHS OF THE l830s _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ The Rescripts of 22 November 1834 and 1 May 1840. _ THE SCHOOLS IH PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION RECORDS _ _ _. _ _ _ _ _ _ The Commis sion to Consider Danish West Indian Questions _ Peter von Scholten's schoolplan _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ THE HORHYIAHS THE START ~<ST l I I I I I I I I ll l I I I I I I Construction and opening of the first school _ _ The language _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Stow's training system _ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ The Training System on the Virgin Islands _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ PRINCESS SCHOOL 18411845 _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ The teachers (40); The number of pupils (41): Prin cess School district (42): Attendance (43); School days and free days (47); Visitors (48) SATURDAYHSCOOLS _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ SUHDHYFSCHOOLS ST THOHAS _ _ The country schools _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ The town school of Charlotte Amalie _ _ _ _ _ ST JOHN FRQH HISSIOH SCHOOLS TO COUNTRY SCHOOLS _ _ The mission schools _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Planning the public schools on St John _ _ _ _ The country schools on St John _ _ _ _ _ SCHOOL REGULRTIOHS _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ EHAHCIPATIOH _ I I i I | I I I I I r I I I I I I I I I I Administrative effects on the country schools _ _ The Moravian view _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ COHCLUSIOHS _ HPPEHDIK A: "A teacher's library" _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ APPEHDIX B: Moravians and others working at the schools _ HAHUSCRIPT SOURCES _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ The National Archive, Copenhagen. -

Edward Bliss Emerson the Caribbean Journal And

EDWARD BLISS EMERSON THE CARIBBEAN JOURNAL AND LETTERS, 1831-1834 Edited by José G. Rigau-Pérez Expanded, annotated transcription of manuscripts Am 1280.235 (349) and Am 1280.235 (333) (selected pages) at Houghton Library, Harvard University, and letters to the family, at Houghton Library and the Emerson Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society. 17 August 2013 2 © Selection, presentation, notes and commentary, José G. Rigau Pérez, 2013 José G. Rigau-Pérez is a physician, epidemiologist and historian located in San Juan, Puerto Rico. A graduate of the University of Puerto Rico, Harvard Medical School and Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, he has written articles on public health, infectious diseases, and the history of medicine. 3 CONTENTS EDITOR'S NOTE .................................................................................................................................. 5 1. 'Ninety years afterward': The journal's discovery ....................................................................... 5 2. Previous publication of the texts .................................................................................................. 6 3. Textual genealogy: Ninety years after 'Ninety years afterward' ................................................ 7 a. Original manuscripts of the journal ......................................................................................... 7 b. Transcription history ................................................................................................................. -

Emancipation in St. Croix; Its Antecedents and Immediate Aftermath

N. Hall The victor vanquished: emancipation in St. Croix; its antecedents and immediate aftermath In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 58 (1984), no: 1/2, Leiden, 3-36 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl N. A. T. HALL THE VICTOR VANQUISHED EMANCIPATION IN ST. CROIXJ ITS ANTECEDENTS AND IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH INTRODUCTION The slave uprising of 2-3 July 1848 in St. Croix, Danish West Indies, belongs to that splendidly isolated category of Caribbean slave revolts which succeeded if, that is, one defines success in the narrow sense of the legal termination of servitude. The sequence of events can be briefly rehearsed. On the night of Sunday 2 July, signal fires were lit on the estates of western St. Croix, estate bells began to ring and conch shells blown, and by Monday morning, 3 July, some 8000 slaves had converged in front of Frederiksted fort demanding their freedom. In the early hours of Monday morning, the governor general Peter von Scholten, who had only hours before returned from a visit to neighbouring St. Thomas, sum- moned a meeting of his senior advisers in Christiansted (Bass End), the island's capital. Among them was Lt. Capt. Irminger, commander of the Danish West Indian naval station, who urged the use of force, including bombardment from the sea to disperse the insurgents, and the deployment of a detachment of soldiers and marines from his frigate (f)rnen. Von Scholten kept his own counsels. No troops were despatched along the arterial Centreline road and, although he gave Irminger permission to sail around the coast to beleaguered Frederiksted (West End), he went overland himself and arrived in town sometime around 4 p.m. -

By the Becreu^ 01 Uio Luterior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-0018 FORT FREDERIK (U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS) Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service____________________________ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form l^NAMEOF PROPERTY Historic Name: FORT FREDERIK (U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS) Other Name/Site Number: FREDERIKSFORT 2. LOCATION Street & Number: S. of jet. of Mahogany Rd. and Rt. 631, N end of Frederiksted Not for publication:N/A City/Town: Frederiksted Vicinity :N/A State: US Virgin Islands County: St. Croix Code: 010 Zip Code:QQ840 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: __ Building(s): X Public-local: __ District: __ Public-State: X Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 2 __ buildings 1 sites 1 __ structures _ objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register :_2 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A tfed a by the becreu^ 01 uio luterior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT FREDERIK (U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS) Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service _______________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Edward Bliss Emerson Journal Project: Qualitative Research by a Non-Hierarchical Team

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The Qualitative Report Books The Qualitative Report 4-2014 The Edward Bliss Emerson Journal Project: Qualitative Research by a Non-Hierarchical Team José G. Rigau-Pérez [email protected] Silvia E. Rabionet Nova Southeastern University College of Pharmacy, [email protected] Annette B. Ramírez de Arellano Wilfredo A. Géigel Alma Simounet Raúl Mayo-Santana Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr_books Part of the Community-Based Learning Commons, Community-Based Research Commons, History Commons, Law Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, and the Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons NSUWorks Citation Rigau-Pérez, José G.; Rabionet, Silvia E.; Ramírez de Arellano, Annette B.; Géigel, Wilfredo A.; Simounet, Alma; and Mayo-Santana, Raúl, "The Edward Bliss Emerson Journal Project: Qualitative Research by a Non-Hierarchical Team" (2014). The Qualitative Report Books. 2. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr_books/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the The Qualitative Report at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Qualitative Report Books by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Edward Bliss Emerson Journal Project: Qualitative Research by a Non-Hierarchical Team José G. Rigau-Pérez, Silvia E. Rabionet, Annette B. Ramírez de Arellano, Wilfredo A. Géigel, Alma Simounet, and Raúl Mayo-Santana Photo Credit for Cover San Juan, Puerto Rico, view from the south, across the bay. Watercolor by unknown author, ca. 1824. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington, D. C., control no. -

FORT CHRISTIAN Other Name/Site Nu

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 FORT CHRISTIAN Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: FORT CHRISTIAN Other Name/Site Number: Christians Fort 2. LOCATION Street & Number: N/A Not for publication: N/A City/Town: Charlotte Amalie Vicinity: X State: US Virgin Islands County: St. Thomas Code: 030 Zip Code: 00802 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): JL Public-Local: _ District: _ Public-State: JL Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object:_ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Nonconrributing 1 1 buildings _ sites _ structures _ objects 1 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT CHRISTIAN Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service__________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Contributing Noncontributing ___Buildings 1 Sea

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM NPS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-0018 FORT FREDERIK Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Fort Frederik Other Name/Site Number: Frederiksfort 2. LOCATION Street & Number: N/A Not for publication:M/A City/Town: Frederiksted Vicinity:MZA State: US Virgin Islands County: St. Croix Code: 010 Zip Code:00840 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private:__ Building(s); X Public-local:__ District:__ Public-State; X Site:__ Public-Federal:__ Structure:__ Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ____ ____ buildings _______ 1 sites 1 Sea Battery ___ structures ____ ____ objects 1 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A RECEIVED 2280 NFS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP 1 ;gistra 8-TOT———— • OMB No. 1024-0018 FORT FREDERIK Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service SrH - 5fl»»> Regis< sr of Historic Pkces Registration Form nni, ncuioitrt ur *p« 4. STATE /FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION RK SERVICE •>Cv> As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

NOAA Series on U.S. Caribbean Fishing Communities Cruzan

` NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-597 NOAA Series on U.S. Caribbean Fishing Communities Cruzan Fisheries: A rapid assessment of the historical, social, cultural and economic processes that shaped coastal communities’ dependence and engagement in fishing in the island of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands By Manuel Valdés-Pizzini University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez, Puerto Rico Juan J. Agar Southeast Fisheries Science Center, Miami, Florida Kathi Kitner Intel Corporation, Portland, Oregon Carlos García-Quijano University of Puerto Rico, Cayey, Puerto Rico Michael Tust and Francesca Forrestal Division of Marine Affairs and Policy, University of Miami Social Science Research Group Southeast Fisheries Science Center NOAA Fisheries 75 Virginia Beach Drive Miami, Florida 33149 January 2010 NOAA Memorandum NMFS-SEFSC-597 NOAA Series on U.S. Caribbean Fishing Communities Cruzan Fisheries: A rapid assessment of the historical, social, cultural and economic processes that shaped coastal communities’ dependence and engagement in fishing in the island of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands By Manuel Valdés-Pizzini University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez, Puerto Rico Juan J. Agar Southeast Fisheries Science Center, Miami, Florida Kathi Kitner Intel Corporation, Portland, Oregon Carlos García-Quijano University of Puerto Rico, Cayey, Puerto Rico Michael Tust and Francesca Forrestal Division of Marine Affairs and Policy, University of Miami U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Gary Faye Locke, Secretary NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION Jane Lubchenco Undersecretary for Oceans and Atmosphere NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE James W. Balsiger, Acting Assistant Administrator for Fisheries January 2010 This Technical Memorandum series is used for documentation and timely communication of preliminary results, interim reports, or similar special-purpose information. -

Island Journey Island Journey

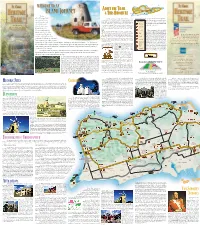

WELCOME TO AN CHRISTIANSTED About the trail ST. CROIX ISLAND JOURNEY & this brochure FREDERIKSTED The St. Croix Heritage Trail As with many memorable journeys, there is no association with each site represent attributes found there, traverses the entire real beginning or end of the trail. You may want to start such as greathouse, windmill, nature, Key to Icons 28 mile length of St. your drive at either Christiansted or Frederiksted as a or viewscape. All St. Croix roads are not portrayed, so do not consider this Croix, linking the point of reference, or you can begin at a point close to Greathouse Your Guide to the where you’re staying. If you want to take it easy, you can a detailed road map. historic seaports of History, Culture, and Nature cover the trail in segments by following particular Sugar Mill of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands Frederiksted and subroutes, such as the “East End Loop,” delineated on the Christiansted with the map. Chimney Please remember to drive on the left, fertile central plain, the The Heritage Trail will take you to three levels of sites: a remnant traffic rule bequeathed by our full-service Attractions that can be toured: Visitation Ruin Danish past. The speed limit along the mountainous Northside, Sites, like churches, with irregular hours; and Points of Trail ranges between 25 and 35 mph, We are proud that the St. Croix Church unless otherwise noted. Seat belts are Heritage Trail has been designated and the arid East End. The r e Interest, which you can view, but are not open to the tl u B one of fifty Millennium Legacy Trails by public. -

Report to Congress on the Historic Preservation of Revolutionary War and War of 1812 Sites in the United States (P.L

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Report to CoCongressngress oonn tthehe HiHistoricstoric PrPreservadoneservation ooff RRevolutionaryevolutionary War anandd War ooff 1812 SiSitestes in the UUnitednited StStatesates Prepared for The Committee on Energy and Natural Resources United States Senate The Committee on Resources United States House of Representatives Prepared by American Battlefield Protection Program National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, DC September 2007 Front Cover Brandywine Battlefield (PA200), position of American forces along Brandywine Creek, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Photo by Chris Heisey. Authorities The Revolutionary War and War of 1812 Historic The American Battlefield Protection Act of 1996, as Preservation Study Act of 1996 amended (P.L. 104-333, Sec. 604; 16 USC 469k). (P.L. 104-333, Section 603; 16 USC 1a-5 Notes). Congress authorized the American Battlefield Protection Congress, concerned that “the historical integrity of Program of the National Park Service to assist citizens, many Revolutionary War sites and War of 1812 sites is at public and private institutions, and governments at all risk,” enacted legislation calling for a study of historic levels in planning, interpreting, and protecting sites where sites associated with the two early American wars. The historic battles were fought on American soil during the purpose of the study was to: “identify Revolutionary War armed conflicts that shaped the growth and development sites and War of 1812 sites, including sites within units of the United States, in order that present and future of the National Park System in existence on the date of generations may learn and gain inspiration from the enactment of this Act [November 12, 1996]; determine the ground where Americans made their ultimate sacrifice. -

A Teaching Material About Danish Colonialism in the West Indies PAGE 2 Our Stories - a Teaching Material About Danish Colonialism in the West Indies

our stories A teaching material about Danish colonialism in the West Indies PAGE 2 Our Stories - A teaching material about Danish colonialism in the West Indies index introduction ..........................................................................................................2 the carribeans before the arrival of the europeans .....................6 from west africa to the west indies ......................................................14 in the west indies ................................................................................................22 a future as free people .....................................................................................34 the fireburn ...........................................................................................................40 the sale to the united states .......................................................................48 reflection ................................................................................................................52 our stories A teaching material about Danish colonialism in the West Indies Museum Vestsjælland: Kasper Nygaard Jensen and Ida Maria R. Skielboe Graphic Design: leoglyhne.dk Translation: Jael Azouley Thanks to Allan Spangsberg Nielsen and History Masterclass 2017 at Næstved Gymnasium, Duane Howard and St. Croix TST students, UNESCO TST-network, Rikke Lie Halberg, Jens Christensen, Bertha Rex Coley, Herman W. von Hesse, La Vaughn Belle, Jens Villumsen, Kwesi Adu, Samantha Nordholt Aagaard and Gunvor Simonsen. The teaching