Luxembourg Report Klaus Schneider, Wolfgang Lorig, Nils C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spaces and Identities in Border Regions

Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Culture and Social Practice Christian Wille, Rachel Reckinger, Sonja Kmec, Markus Hesse (eds.) Spaces and Identities in Border Regions Politics – Media – Subjects Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Natio- nalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de © 2015 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or uti- lized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover layout: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: misterQM / photocase.de English translation: Matthias Müller, müller translations (in collaboration with Jigme Balasidis) Typeset by Mark-Sebastian Schneider, Bielefeld Printed in Germany Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-2650-6 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-2650-0 Content 1. Exploring Constructions of Space and Identity in Border Regions (Christian Wille and Rachel Reckinger) | 9 2. Theoretical and Methodological Approaches to Borders, Spaces and Identities | 15 2.1 Establishing, Crossing and Expanding Borders (Martin Doll and Johanna M. Gelberg) | 15 2.2 Spaces: Approaches and Perspectives of Investigation (Christian Wille and Markus Hesse) | 25 2.3 Processes of (Self)Identification(Sonja Kmec and Rachel Reckinger) | 36 2.4 Methodology and Situative Interdisciplinarity (Christian Wille) | 44 2.5 References | 63 3. Space and Identity Constructions Through Institutional Practices | 73 3.1 Policies and Normalizations | 73 3.2 On the Construction of Spaces of Im-/Morality. -

Oecd Secretary-General Tax Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors

OECD SECRETARY-GENERAL TAX REPORT TO G20 FINANCE MINISTERS AND CENTRAL BANK GOVERNORS Saudi Arabia July 2020 For more information: [email protected] www.oecd.org/tax @OECDtax | 1 OECD Secretary-General Tax Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors Saudi Arabia July 2020 PUBE 2 | This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. Please cite this report as: OECD (2020), OECD Secretary-General Tax Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors – July 2020, OECD, Paris. www.oecd.org/tax/oecd-secretary-general-tax-report-g20-finance-ministers-july-2020.pdf Note by Turkey The information in this document with reference to “Cyprus” relates to the southern part of the Island. There is no single authority representing both Turkish and Greek Cypriot people on the Island. Turkey recognises the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Until a lasting and equitable solution is found within the context of the United Nations, Turkey shall preserve its position concerning the “Cyprus issue”. Note by all the European Union Member States of the OECD and the European Union The Republic of Cyprus is recognised by all members of the United Nations with the exception of Turkey. The information in this document relates to the area under the effective control of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus. -

Communiqué De Presse

Communiqué de presse Etude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA LUXEMBOURG 2014/2015 Les résultats de la dixième édition de l’étude « TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA » réalisée par TNS ILRES et TNS MEDIA sont désormais disponibles. Cette étude qui informe sur l’audience des médias presse, radio, télévision, cinéma, dépliants publicitaires et Internet a été commanditée par les trois grands groupes de médias du pays: Editpress SA ; IP Luxembourg/CLT-UFA et Saint-Paul Luxembourg SA. L’étude a également été soutenue par le Gouvernement luxembourgeois. Depuis sa 1ère édition conduite en 2005-2006, l’étude Plurimédia était exclusivement réalisée moyennant un sondage téléphonique assisté par ordinateur (CATI). Considérant les évolutions de la société luxembourgeoise en matière d’usage des télécommunications et d’Internet, cette dixième édition de l’enquête est basée pour partie sur des enquêtes téléphoniques, pour une autre par Internet. L’objectif étant d’élargir la base de sondage et ainsi assurer une plus grande représentativité des résultats. L’étude TNS ILRES PLURIMEDIA a donc été réalisée auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire de 4.103 personnes (3.011 par téléphone, 1 092 par internet), représentatif de la population résidant au Grand-duché de Luxembourg, âgée de 12 ans et plus. Alors que la mesure d’audience des titres de presse se base sur l’univers des personnes âgées de 15 ans et plus, les résultats d’audience des autres médias se réfèrent supplémentairement sur l’univers 12+. Le terrain d’enquête s’est déroulé d’octobre 2014 à fin mai 2015. Ci-après, vous trouverez quelques chiffres clés, concernant le lectorat moyen par période de parution, c’est-à-dire le lectorat par jour moyen pour les quotidiens, le lectorat par semaine moyenne pour les hebdomadaires, et ainsi de suite. -

Bibliographie Courante De La Littérature Luxembourgeoise 2010

GRAND-DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE Daphné BOEHLES Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise BIBLIOGRAPHIE LITTÉRAIRE 2010 2010 (23e année) et compléments des années précédentes 2011 CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE BIBLIOGRAPHIE LITTÉRAIRE 2010 Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise 2010 1 Impressum: Editeur: Centre national de littérature 2, rue E. Servais L-7565 Mersch 2011 Tirage: 600 exemplaires Imprimerie: Hengen ISSN 1016-328X 2 MINISTÈRE DE LA CULTURE Daphné BOEHLES Bibliographie courante de la littérature luxembourgeoise 2010 (23e année) et compléments des années précédentes CENTRE NATIONAL DE LITTÉRATURE MERSCH 2011 3 Sommaire Avant-propos p. 7 Photographies et abréviations p. 8 1 Linguistique et politique linguistique p. 9 2 Anthologies, bibliographies et ouvrages de référence p. 26 3 Histoire et critique p. 32 3-1 Essais et articles généraux p. 32 3-2 Auteurs luxembourgeois p. 45 3-3 Auteurs étrangers p. 59 4 Littérature d’expression luxembourgeoise p. 140 4-1 Livres p. 140 4-2 Contributions p. 143 4-3 Critiques p. 152 5 Littérature d’expression française p. 160 5-1 Livres p. 160 5-2 Contributions p. 169 5-3 Critiques p. 183 6 Littérature d’expression allemande p. 192 6-1 Livres p. 192 6-2 Contributions p. 203 6-3 Critiques p. 226 7 Littérature d’expression diverse p. 242 7-1 Livres p. 242 7-2 Contributions p. 253 7-3 Critiques p. 260 8 Traductions p. 268 8-1 Traductions par des auteurs luxembourgeois p. 268 8-2 Traductions d’auteurs luxembourgeois p. 268 9 Cabaret et théâtre p. -

REPORT from the 1St Policynet Study Visit to the Grande Region

“Regional Support for Inclusive Education” REPORT from the 1st PolicyNet Study Visit to the Grande Region “Region to region – exchange of educational experience” Background The project “Regional Support for Inclusive Education”promotes the concept of inclusive education in South East Europe (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, "the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" and Kosovo1) as a reform principle that respects and caters for diversity amongst all learners, with a specific focus on those who are at a higher risk of marginalisation and exclusion. The Project supports and facilitates a multi-level, cross-sectorial regional network (Inclusive PolicyNet) with a constant composition, representing a broad range of stakeholders (policymakers - from education, social protection and healthcare sectors, from the central and local level; practitioners – school principals, members of school boards, representatives of education inspectorates, researchers and teacher educators, civil society representatives, parents) to exchange experience and discuss inclusive education issues, as well as common challenges and promising policy approaches or examples of good practice from the European Union and the region. Within the project, The “Inclusive PolicyNet” will produce concrete policy recommendations at each education level (Primary Education, General Secondary Education and Vocational Education and Training). As capacity building and policy learning activity the study visit to Greater Region was organized for seven (7) Inclusive PolicyNet members. The Greater Region is the area of Saarland, Lorraine, Luxembourg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Wallonia and the rest of the French Community of Belgium, and the German-speaking Community of Belgium. This region has a similar heritage but also rich diversity and was therefore an excellent partner for mutual learning and exchange of experience with similar yet diverse South East Europe. -

The European Committee of the Regions and the Luxembourg Presidency of the European Union

EUROPEAN UNION Committee of the Regions © Fabrizio Maltese / ONT The European Committee of the Regions and the Luxembourg Presidency of the European Union 01 Foreword by the president of the European Committee of the Regions 3 02 Foreword by the prime minister of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg 5 03 Role of the European Committee of the Regions 7 04 The Luxembourg delegation to the European Committee of the Regions 10 Members of the Luxembourg delegation 10 Interview with the president of the Luxembourg delegation 12 Viewpoints of the delegation members 14 05 Cross-border cooperation 22 Joint interview with Corinne Cahen, Minister for the Greater Region, and François Bausch, Minister for Sustainable Development and Infrastructure 22 Examples of successful cross-border cooperation in the Greater Region 26 EuRegio: speaking for municipalities in the Greater Region 41 06 Festivals and traditions 42 07 Calendar of events 46 08 Contacts 47 EUROPEAN UNION Committee of the Regions © Fabrizio Maltese / ONT Foreword by the president of the 01 European Committee of the Regions Economic and Monetary Union,, negotiations on TTIP and preparations for the COP21 conference on climate change in Paris. In this context, I would like to mention some examples of policies where the CoR’s work can provide real added value. The European Committee of the Regions wholeheartedly supports Commission president Jean-Claude Junker’s EUR 315 billion Investment Plan for Europe. This is an excellent programme intended to mobilise public and private investment to stimulate the economic growth that is very The dynamic of the European Union has changed: much needed in Europe. -

ARNY SCHMIT (Luxembourg, 1959)

ARNY SCHMIT (Luxembourg, 1959) Arny Schmit is a storyteller, a conjurer, a traveler of time and space. From the myth of Leda to the images of an exhibitionist blogger, from the house of a serial killer to the dark landscapes of a Caspar David Friedrich, he makes us wander through a universe that tends towards the sublime. Manipulating the mimetic properties of painting while referring to the virtual era in which we live, the Luxembourgish artist likes to surprise by playing on the false pretenses. In his paintings he creates bridges between reality, fantasy and nightmare. The medieval, baroque or romantic references reveal his profound respect for the masters of the past. Extracted from a different time era, decorative motifs populate his compositions like so many childhood memories, from the floral wallpaper to the dusty Oriental carpet, through the models of embroidery. Through fragmentation, juxtaposition and collage, Arny Schmit multiplies the reading tracks and digs the strata of the image. The beauty of his women contrasts with their loneliness and sadness, the enticing colors are soiled with spurts, the shapes are torn to reveal the underlying, the reverse side of the coin, the unknown. 1 EXHIBITION – DECEMBER 1st, 2018 to FEBRUARY 28th, 2019 ARNY SCHMIT – WILD 13 windows with a view on the wilderness. Recent works by Luxembourgish painter Arny Schmit depict his vision of a daunting and nurturing nature and its relationship with the female body. A body that Schmit likes to fragment by imprisoning it into frames of analysis, each frame a clue into a mysterious narrative, a suggestion, an impression. -

Call for Papers

International conference in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg 5 and 6 May 2022 Conference location: Chambre des salariés du Luxembourg (CSL), 2-4 Rue Pierre Hentges Luxembourg-Ville 1 Topic of the conference Living in one country and working in another is a daily reality for thousands of people in Europe. Taking into account the EU-28 countries and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries, the total number of frontier workers in Europe was 1.9 million in 2017 (European Commission, 2018). The growth of flows of cross-border work, as well as its socio-economic, political and legal dimensions, are increasingly relevant to further analysis. It is a subject at the center of much analysis in different disciplines in the social sciences, humanities and environmental studies. Cross-border work has developed between European countries long before the foundation of the European Economic Community established by the Treaty of Rome (Lentacker, 1973; Ricq, 1981). Cross-border work has become an important economic, social and human phenomenon within border territories in Europe (Van Houtum, 2000; Haas and Osland, 2014; Rietveld, 2012), the characteristics of which will be questioned during the conference. The main countries of residence of cross-border commuters are France (405,000 or 21% of the total number of cross-border commuters), Germany (249,000 or 13%) and Poland (202,000 or 11%) (European Commission, 2018). The main countries of employment are Germany (391,000), Switzerland (387,000), Luxembourg (186,000) and Austria (175,000) in 2017. As shown by studies on the Greater Region (Saar-Lorraine-Luxembourg-Wallonia-Rhineland- Palatinate), one of the most important areas of cooperation in Europe (Wille, 2012; Belkacem/Pigeron-Piroth, 2012; Wille, 2016; Wille/Nienaber 2020), the geographical situation on the border, the regulatory standardisation of cross-border work, the connection of spaces by traffic infrastructures, etc. -

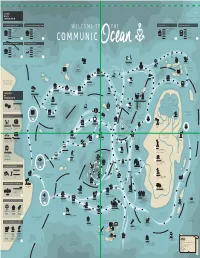

51% 49% 71% 16% 16%

THE WAY WE USE MERKUR - INF OGRAPHIC - C OMMUNICOCEAN - MA Y/JUNE 2015 COMMUNICATION USE OF DAILY NEWSPAPERS (TOP 5) USE OF WEEKLY & BI MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF TV-STATIONS USE OF WEB-SITES (TOP 5) 39,0% LUXEMBURGER WORT 32,8% AUTOTOURING 25,2% RTL TELE LETZEBUERG 25,7% RTL.LU 29,5% L´ESSENTIEL 14,3% AUTO REVUE 3,8% NORDLIICHT TV 16,9% WORT.LU 9,3% TAGEBLATT 13,9% AUTOMOTO 2,1% CHAMBER TV 11,3% L´ESSENTIEL.LU 5,7% LE QUOTIDIEN 11,3% PAPERJAM ... ... 9,2% PUBLIC.LU 2,1% LETZEBUERGER JOURNAL 9,6% CITY MAG ... ... 4,7% TAGEBLATT.LU USE OF MONTHLY MAGAZINES (TOP 5) USE OF RADIO-SATIONS (TOP 5) 23,0% TÉLÉCRAN 36,8% RTL RADIO LETZEBUERG 17,0% LUX-POST WEEK-END 19,6% ELDORADIO 15,7% REVUE 8,5% RTL (GERMAN LANGUAGE) 12,1% CONTACTO 5,4% RADIO LATINA 7,7% LUXBAZAR 4,5% RADIO 100,7 NEW IDEA PRINT MEDIA STORY TELLING 2010s - PRINT NATIVE IN DANGER ADVERTISING MESSENGERS SEA OF PRINT CREATIVITY TRENDY COAST TEXTUAL C ONTENT FRESH IDEAS ISLANDS BUSINESS PLAN FREE NEW SPAPER INFOGRAPHICS 2007 - 1st ISSUE OF L’ESSENTIEL BIG BUDGET FEE / DUTY MAGAZINE MESSENGERS DATA 1932 - 1st MA GAZINE VISUALIZATION CONTINENT AUTOTOURING BY CONSEIL DE AUTOMOBILE CLUB PRESSE M PICTURES A NEWSPAPER I 1848 - 1st ISSUE OF N PRINTING NEWSPAPER RACING PIGE ON LUXEMBURGER WORT S THE HISTORY 1900s - 1st ME CHANIC 1913 - 1st ISSUE 776 B.C. - WINNER LIST COMPUTER PRINTER OF TAGEBLATT LOW BUDGET T OF OF OLYMPIC GAMES SENT R COMMUNICATION BY DOVES E AGE A LANGUAGE B ARRIER REEF NATIO- M NALITY 70,5% LUXEMBOURGISH N E W S P A P E R 55,7% FRENCH GENDER PROF- A REVOLUTION BEGAN 1650 - 1st DAILY 30,6% GERMAN ESSION AS MANKIND STARTED NEWSPAPER 21,0% ENGLISH TO BIND MESSAGES 20,0% PORTUGUESE TO TIME & TO SPACE BIG BUDGET CONSEIL DE HOBBIES PUBLICITÉ INCOME EDU- CLIENTS FUN CATION COAST HOW DID THEY DO THIS ? PRINT R OUTE REPRODUCTION CLIENTS 1450 - GUTENBER G EMOTIONS BUDGET INVENTS PRINT LETTERS COAST CONFUSION TELEVISION TRIANGLE TIME BINDING DEFINITION 1970 - ST ART OF TV-SPOT VISUAL 30.000 B.C. -

Rédacteurs En Chef De La Presse Luxembourgeoise 93

Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Agenda Plurionet Frank THINNES boulevard Royal 51 L-2449 Luxembourg +352 46 49 46-1 [email protected] www.plurio.net agendalux.lu BP 1001 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 42 82 82-32 [email protected] www.agendalux.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Hebdomadaires d'Lëtzeburger Land M. Romain HILGERT BP 2083 L-1020 Luxembourg +352 48 57 57-1 [email protected] www.land.lu Woxx M. Richard GRAF avenue de la Liberté 51 L-1931 Luxembourg +352 29 79 99-0 [email protected] www.woxx.lu Contacto M. José Luis CORREIA rue Christophe Plantin 2 L-2988 Luxembourg +352 4993-315 [email protected] www.contacto.lu Télécran M. Claude FRANCOIS BP 1008 L-1010 Luxembourg +352 4993-500 [email protected] www.telecran.lu Revue M. Laurent GRAAFF rue Dicks 2 L-1417 Luxembourg +352 49 81 81-1 [email protected] www.revue.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Correio Mme Alexandra SERRANO ARAUJO rue Emile Mark 51 L-4620 DIfferdange +352 444433-1 [email protected] www.correio.lu Le Jeudi M. Jacques HILLION rue du Canal 44 L-4050 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 22 05 50 [email protected] www.le-jeudi.lu Clae services asbl Rédacteurs en chef de la presse luxembourgeoise 93 Quotidiens Zeitung vum Lëtzebuerger Vollek M. Ali RUCKERT - MEISER rue Zénon Bernard 3 L-4030 Esch-sur-Alzette +352 446066-1 [email protected] www.zlv.lu Le Quotidien M. -

Organising Transregional Child Protection Within the Greater Region of France, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg

Social Work & Society ▪▪▪ C. Schröder & U. Zöller: Organising Transregional Child Protection within the Greater Region of France, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg Organising Transregional Child Protection within the Greater Region of France, Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg Christian Schröder, htw saar Ulrike Zöller, htw saar 1 Introduction In the Interreg research project, EUR&QUA (2016-2020), we observed the transregional organisation of child protection in the Greater Region. By referring to the concept of transregional organisation of child protection, we emphasise our perspective in researching the constituting role of boundary-crossing interactions as a characteristic of the modern world. The Greater Region provides a specific example for this. The Greater Region (formerly the SaarLorLux Region) extends over the borders of four nations (the German states of Saarland and Rhineland-Palatinate, the French region of Lorraine, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and the Belgian region of Wallonia as well as the German-speaking community in East Belgium). It can be characterised as a European cooperation area (Schriftenreihe der Großregion, 2018, p. 9). Crossing borders in the Greater Region is part of everyday life for the adults living here. It is interesting to note that children in the Greater Region also cross borders in the context of child and youth welfare. However, the effects of this particular type of border crossing on children, their parents, their siblings and the child and youth welfare organisations are still largely unknown. The nation state forms the quasi natural point of reference in social work. This methodological nationalism (Beck, 2010) has been increasingly questioned in social work against the background of phenomena that cross nation-state borders (Bähr et al., 2014; Schwarzer et al., 2016). -

National Distribution Lists of Media for the "Help" Campaign

LUXEMBOURG Nom du Mediaatt05072611563078719EA79657.xls Rédacteur en chef Ville Presse quotidienne Letzeburger Journal Claude Karger Luxembourg Letzeburger Journal Colette Mart Luxembourg La Voix du Luxembourg Laurent Moyse Luxembourg Le Quotidien Denis Berche Esch-sur-Alzette Luxemburger Wort Léon Zeches / Jean Louis scheffen Luxembourg Tageblatt Alvin Sold/Romain Durlier Esch-sur-Alzette Zeitung vum Letzebuerger Vollek Ali Ruckert Luxembourg Presse Hebdomadaire Contacto José Correia Luxembourg Correio José Dias Luxembourg d'Letzeburger Land Mario Hirsch Luxembourg Le Jeudi Jacques Hillion Esch-sur-Alzette Revue Stefan Kunzmann Luxembourg Revue Claude Wolf Luxembourg Télécran Roland Arens Luxembourg Télécran Martine Folscheid Luxembourg Télécran Britta Schlueter Luxembourg Woxx Robert Garcia Luxembourg Presse Mensuelle Agefi Luxembourg Olivier Minguet Capellen Femmes Magazine Maria Pietrangelli Luxembourg Le Monde Diplomatique Francis Wagner Esch-sur-Alzette Nico Mike Koedinger Luxembourg paperJam Jean Michel Gaudron Luxembourg paperJam Francis Gasparotto Luxembourg paperJam Ludivine Plessy Luxembourg paperJam Florence Reinson Luxembourg RADIO DNR Isabelle Decker Luxembourg DNR Radio Jean-Marc Sturm Luxembourg Eldoradio Isabel Galiano / ivano Andressini Luxembourg Radio ARA Radio Latina Gomes Avelinos Luxembourg Radio socio-culturelle 100,7 Fernand Weides Luxembourg RTL Radio Letzebuerg Marc Linster Luxembourg Radio Latina Gomes Avelinos Luxembourg Radio Latina Serge Ferreira Luxembourg TELEVISION att05072611563078719EA79657.xls TTV Daniel