Complete Dissertation.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Local History of Ethiopia an - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia An - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) an (Som) I, me; aan (Som) milk; damer, dameer (Som) donkey JDD19 An Damer (area) 08/43 [WO] Ana, name of a group of Oromo known in the 17th century; ana (O) patrikin, relatives on father's side; dadi (O) 1. patience; 2. chances for success; daddi (western O) porcupine, Hystrix cristata JBS56 Ana Dadis (area) 04/43 [WO] anaale: aana eela (O) overseer of a well JEP98 Anaale (waterhole) 13/41 [MS WO] anab (Arabic) grape HEM71 Anaba Behistan 12°28'/39°26' 2700 m 12/39 [Gz] ?? Anabe (Zigba forest in southern Wello) ../.. [20] "In southern Wello, there are still a few areas where indigenous trees survive in pockets of remaining forests. -- A highlight of our trip was a visit to Anabe, one of the few forests of Podocarpus, locally known as Zegba, remaining in southern Wello. -- Professor Bahru notes that Anabe was 'discovered' relatively recently, in 1978, when a forester was looking for a nursery site. In imperial days the area fell under the category of balabbat land before it was converted into a madbet of the Crown Prince. After its 'discovery' it was declared a protected forest. Anabe is some 30 kms to the west of the town of Gerba, which is on the Kombolcha-Bati road. Until recently the rough road from Gerba was completed only up to the market town of Adame, from which it took three hours' walk to the forest. A road built by local people -- with European Union funding now makes the forest accessible in a four-wheel drive vehicle. -

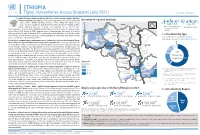

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Oromo Indigenous Religion: Waaqeffannaa

Volume III, Issue IV, April 2016 IJRSI ISSN 2321 – 2705 Oromo Indigenous Religion: Waaqeffannaa Bedassa Gebissa Aga* *Lecturer of Human Rights at Civics and Ethical Studies Program, Department of Governance, College of Social Science, of Wollega University, Ethiopia Abstract: This paper discusses the African Traditional religion on earth. The Mande people of Sierra-Leone call him as with a particular reference to the Oromo Indigenous religion, Ngewo which means the eternal one who rules from above.3 Waaqeffannaa in Ethiopia. It aimed to explore status of Waaqeffannaa religion in interreligious interaction. It also Similar to these African nations, the Oromo believe in and intends to introduce the reader with Waaqeffannaa’s mythology, worship a supreme being called Waaqaa - the Creator of the ritual activities, and how it interrelates and shares with other universe. From Waaqaa, the Oromo indigenous concept of the African Traditional religions. Additionally it explains some Supreme Being Waaqeffanna evolved as a religion of the unique character of Waaqeffannaa and examines the impacts of entire Oromo nation before the introduction of the Abrahamic the ethnic based colonization and its blatant action to Oromo religions among the Oromo and a good number of them touched values in general and Waaqeffannaa in a particular. For converted mainly to Christianity and Islam.4 further it assess the impacts of ethnic based discrimination under different regimes of Ethiopia and the impact of Abrahamic Waaqeffannaa is the religion of the Oromo people. Given the religion has been discussed. hypothesis that Oromo culture is a part of the ancient Cushitic Key Words: Indigenous religion, Waaqa, Waaqeffannaa, and cultures that extended from what is today called Ethiopia Oromo through ancient Egypt over the past three thousand years, it can be posited that Waaqeffannaa predates the Abrahamic I. -

Historical Survey of Limmu Genet Town from Its Foundation up to Present

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 6, ISSUE 07, JULY 2017 ISSN 2277-8616 Historical Survey Of Limmu Genet Town From Its Foundation Up To Present Dagm Alemayehu Tegegn Abstract: The process of modern urbanization in Ethiopia began to take shape since the later part of the nineteenth century. The territorial expansion of emperor Menelik (r. 1889 –1913), political stability and effective centralization and bureaucratization of government brought relative acceleration of the pace of urbanization in Ethiopia; the improvement of the system of transportation and communication are identified as factors that contributed to this new phase of urban development. Central government expansion to the south led to the appearance of garrison centers which gradually developed to small- sized urban center or Katama. The garrison were established either on already existing settlements or on fresh sites and also physically they were situated on hill tops. Consequently, Limmu Genet town was founded on the former Limmu Ennarya state‘s territory as a result of the territorial expansion of the central government and system of administration. Although the history of the town and its people trace many year back to the present, no historical study has been conducted on. Therefore the aim of this study is to explore the history of Limmu Genet town from its foundation up to present. Keywords: Limmu Ennary, Limmu Genet, Urbanization, Development ———————————————————— 1. Historical Background of the Study Area its production. The production and marketing of forest coffee spread the fame and prestige of Limmu Enarya ( The early history of Limmu Oromo Mohammeed Hassen, 1994). The name Limmu Ennarya is The history of Limmu Genet can be traced back to the rise derived from a combination of the name of the medieval of the Limmu Oromo clans, which became kingdoms or state of Ennarya and the Oromo clan name who settled in states along the Gibe river basin. -

The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published Online: 14 Apr 2013

This article was downloaded by: [US Naval Academy] On: 25 June 2013, At: 06:09 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Journal of the Middle East and Africa Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujme20 The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961) Nikolaos Biziouras Published online: 14 Apr 2013. To cite this article: Nikolaos Biziouras (2013): The Genesis of the Modern Eritrean Struggle (1942–1961), The Journal of the Middle East and Africa, 4:1, 21-46 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2013.771419 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection -

History of Events and Internal Developement. the Example of The

Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies University of Addis Ababa, 1984 Edited by Dr Taddese Beyene Volume 1 isbn — Volume 1: 1 85450 000 7 Institute of Ethiopian Studies, Addis Ababa 1988 Table of Contents Preface Opening Address The New Ethiopia: Major Defining Characteristics. Research Trends in Ethiopian Studies at Addis Ababa University over the last Twenty-Five Years. Prehistory and Archaeology Early Stone Age Cultures in Ethiopia. Alemseged Abbay Les Monuments Gondariens des XVIIe et XVIIIe Steeles. Une Vue d'ensemble. Francis Anfray Le Gisement Paleolithique de Melka-Kunture. Evolution et Culture. Jean Chavaillon A Review of the Archaeological Evidence for the Origins of Food Production in Ethiopia. John Desmond Clark Reflections on the Origins of the Ethiopian Civilization. Ephraim Isaac and Cain Felder Remarks on the Late Prehistory and Early History of Northern Ethiopia. Rodolfo Fattovich History to 1800 Is Näwa Bäg'u an Ethiopian Cross? Ewa Balicka-Witakowska The Ruins of Mertola-Maryam. Stephen Bell Who Wrote "The History of King Sarsa Dengel" - Was it the Monk Bahrey? S. B. Chernetsov Les Affluents de la Rive Droite du Nil dans la Geographie Antique. Jehan Desanges Ethiopian Attitudes towards Europeans until 1750. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski The Ta'ämra 'Iyasus: a study of textual and source-critical problems. S. Gem The Mediterranean Context for the Medieval Rock-Cut Churches of Ethiopia. Michael Gerven Introducing an Arabic Hagiography from Wällo Hussein Ahmed Some Hebrew Sources on the Beta-Israel (Falasha). Steven Kaplan The Problem of the Formation of the Peasant Class in Ethiopia. Yu. M. Kobischanov The Sor'ata Gabr - a Mirror View of Daily Life at the Ethiopian Royal Court in the Middle Ages. -

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 and Reassessment of Crop

Ethiopia Bellmon Analysis 2015/16 And Reassessment Of Crop Production and Marketing For 2014/15 October 2015 Final Report Ethiopia: Bellmon Analysis - 2014/15 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................ iii Table of Acronyms ................................................................................................................................................. iii Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................. 10 Economic Background ......................................................................................................................................... 11 Poverty ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Wage Labor ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 Agriculture Sector Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

Determinants of Loan Repayment Performance of Smallholder Farmers in Horro and Abay Choman Woredas of Horoguduru- Wollega Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia

Journal of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development Vol. 5(3), pp. 648-655, December, 2019. © www.premierpublishers.org, ISSN: 2167-0477 Research Article Determinants of Loan Repayment Performance of Smallholder Farmers in Horro and Abay Choman woredas of Horoguduru- Wollega Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia *1Amsalu File, 2Oliyad Sori 1Wollega University, The Campus’s Finance Head, P.O. Box 38, Ethiopia 2Wollega University, Department of Agricultural Economics, P.O. Box 38, Ethiopia Credit repayment is one of the dominant importance for viable financial institutions. This study was aimed to identify determinants of loan repayment capacity of smallholder farmers in Horro and Abay-Chomen Woredas. The study used primary data from a sample of formal credit borrower farmers in the two woredas through structured questionnaire. A total of 120 farm households were interviewed during data collection and secondary data were collected from different organizations. The logit model results indicated that a total of fourteen explanatory variables were included in the model of which six variables were found to be significant.; among these variables, family size and expenditure in social ceremonies negatively while, credit experience, livestock, extension contact and income from off-farm activities positively influenced the loan repayment performance of smallholder farmers in the study areas. Based on the result, the study recommended that the lending institution should give attention on loan supervision and management while the borrowers should give attention on generating alternative source of income to pay the loans which is vital as it provides information that would enable to undertake effective measures with the aim of improving loan repayment in the study area. -

Vulnerability Analysis of Smallholder

Tessema and Simane Ecological Processes (2019) 8:5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-019-0159-7 RESEARCH Open Access Vulnerability analysis of smallholder farmers to climate variability and change: an agro- ecological system-based approach in the Fincha’a sub-basin of the upper Blue Nile Basin of Ethiopia Israel Tessema1,2* and Belay Simane1 Abstract Background: Ethiopia is frequently cited as a country that is highly vulnerable to climate variability and change. The country’s high vulnerability arises mostly from climate-sensitive agricultural sector that suffers a lot from risks associated with rainfall variability. The vulnerability factors (exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity) of the agricultural livelihoods to climate variability and change differ across agro-ecological systems (AESs). Therefore, the aim of this study was to analyze AES-specific vulnerability of smallholder farmers to climate variability and change in the Fincha’a sub-basin. We surveyed 380 respondents from 4 AESs (highland, midland, wetland, and lowland) randomly selected. Furthermore, focus group discussion and key informant interviews were also performed to supplement and substantiate the quantitative data. Livelihood vulnerability index was employed to analyze the levels of smallholders’ agriculture vulnerability to climate variability and change. Data on socioeconomic and biophysical attribute were collected and combined into the indices and vulnerability score was calculated for each agro-ecological system. Results: Considerable variation was observed across the agro-ecological systems in profile, indicator, and the three livelihood vulnerability indices-Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change dimensions (exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity) of vulnerability. The lowland AES exhibited higher exposure, low adaptive capacity, and high vulnerability, while the midland AES demonstrated lower exposure, higher adaptive capacity, and lower vulnerability. -

Bibliographic Guide to Further Reading

BIBLIOGRAPHIC GUIDE TO FURTHER READING The historical, memoir, travel, and technical literature on Ethiopia is immense and continually growing. A complete bibliography would require a very thick volume. Included below are most of the major books cited in the text. Journal articles, pamphlets and monographs are not included. Many worthwhile books from my own collection not specifically referenced in the footnotes have been added. Books in languages other than English, German, French, Italian and Portu guese are not listed. Among the most valuable sources for research on Ethiopia are the proceedings of the triennial International Ethiopian Studies Conferences (IESC), the most recent of which were held in East Lansing, Michigan in September 1994 and in Kyoto,Japan in Decem ber 1997. The former produced 2,372 pages of papers published as New Trends in Ethiopian Studies (2 vols. Red Sea Press, No. 1994). The latter resulted in 2,345 pp. of papers published as Ethiopia in Broader Perspective (Shokado, Kyoto, 1997, 3vols). The 14th IESC is scheduled to take place in Addis Ababa in November 2000. Many other volumes of conference proceedings have been published in Ethiopia and elsewhere during the past three decades. With only a few except ions, these have not been listed below. HISTORY AND CULTURE, GENERAL Berhanou Abebe, Historie de lithiopie d'Axoum ala revolution, Maison neuve et Larose, Paris, 1998. E. A. Wallis Budge, History ofEthiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia, Methuen, London, 192R David Buxton, The Abyssinians, Thames & Hudson, London, 1970. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski, Ethiopia sAccess to the Sea, EJ. Brill, Leiden, 1985. Jean Doresse, Ethiopia, Elee, London, 1959. -

Socio-Economic Base-Line Survey of Rural and Urban Households in Tana Sub-Basin, Amhara National Regional State

Socio-Economic Base-Line Survey of Rural and Urban Households in Tana Sub-Basin, Amhara National Regional State Kassahun Berhanu & Tegegne Gebre-Egziabher FSS Monograph No. 10 Forum for Social Studies (FSS) Addis Ababa © 2014 Forum for Social Studies (FSS) All rights reserved. Printed in Addis Ababa Typesetting & Layouts: Konjit Belete ISBN: 13: 978-99944-50-49-7 Forum for Social Studies (FSS) P.O. Box 25864 code 1000 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Email: [email protected] Web: www.fssethiopia.org.et This monograph has been published with the financial support of the Civil Societies Support Program (CSSP). The contents of the monograph are the sole responsibilities of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the CSSP or the FSS. Table of Contents List of Tables vii Acronyms xvii I. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and Statement of the Problem 1 1.2 Objectives 9 1.3 Research Questions (Issues) 10 1.4 Methodology 11 1.4.1 Sampling 11 1.4.2 Types of Data, Data collection techniques, and 13 Data Sources 1.5 Significance and Policy Implications 15 1.6 Organization of the Report 15 II. POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS OF RURAL 17 HOUSHOLDS 2.1 Age-Sex Composition 17 2.2 Household Composition and Marital Status 20 2.3 Ethnic and Religious Composition 22 2.4 Educational characteristics 22 2.5 Primary Activity 25 III. AGRICULTURE 27 3.1 Crop Production 27 3.1.1 Land Ownership 27 3.1.2 Number of Plots Owned and Average Distance 28 Traveled to Farm Plots 3.1.3 Size of holding (ha) 29 3.1.4 Other Forms of Land Holding by Respondents 30 in Study Woredas 3.1.5 Possession of Private Fallow and Grazing Land 31 3.1.6 Land Use Certification and Security of Tenure 32 3.1.7 Possession of Plough Oxen 33 3.1.8 Usage of Farm Implements 33 3.1.9 Means and Ways of Engaging in Farming 34 Activities 3.1.10 Annual Production (Base Year 2004 EC) 38 3.1.11 Use of Agricultural Inputs 38 3.1.12 Irrigated Agriculture 42 3.2 Livestock Production and Services 47 IV.