Arthur B. Davies in the West, 1905

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gelett Burgess - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Gelett Burgess - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Gelett Burgess(30 January 1866 – 18 September 1951) Frank Gelett Burgess was an artist, art critic, poet, author and humorist. An important figure in the San Francisco Bay Area literary renaissance of the 1890s, particularly through his iconoclastic little magazine, The Lark, he is best known as a writer of nonsense verse. He was the author of the popular Goops books, and he invented the blurb. <b>Early life</b> Born in Boston, Burgess was "raised among staid, conservative New England gentry". He attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduating with a B.S. in 1887. After graduation, Burgess fled conservative Boston for the livelier bohemia of San Francisco, where he took a job working as a draftsman for the Southern Pacific Railroad. In 1891, he was hired by the University of California at Berkeley as an instructor of topographical drawing. <b>Cogswell fountain incident</b> In 1894, Burgess lost his job at Berkeley as a result of his involvement in an attack on one of San Francisco's three Cogswell fountains, free water fountains named after the pro-temperance advocate Henry Cogswell who had donated them to the city in 1883. As the San Francisco Call noted a year before the incident, Cogswell's message, combined with his enormous image, irritated many: <i>It is supposed to convey a lesson on temperance, as the doctor stands proudly on the pedestal, with his whiskers flung to the rippling breezes. In his right hand he holds a temperance pledge rolled up like a sausage, and the other used to contain a goblet overflowing with heaven's own nectar. -

NEO-Orientalisms UGLY WOMEN and the PARISIAN

NEO-ORIENTALISMs UGLY WOMEN AND THE PARISIAN AVANT-GARDE, 1905 - 1908 By ELIZABETH GAIL KIRK B.F.A., University of Manitoba, 1982 B.A., University of Manitoba, 1983 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Fine Arts) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA . October 1988 <£> Elizabeth Gail Kirk, 1988 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Fine Arts The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 Date October, 1988 DE-6(3/81) ABSTRACT The Neo-Orientalism of Matisse's The Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, both of 1907, exists in the similarity of the extreme distortion of the female form and defines the different meanings attached to these "ugly" women relative to distinctive notions of erotic and exotic imagery. To understand Neo-Orientalism, that is, 19th century Orientalist concepts which were filtered through Primitivism in the 20th century, the racial, sexual and class antagonisms of the period, which not only influenced attitudes towards erotic and exotic imagery, but also defined and categorized humanity, must be considered in their historical context. -

Suzanne Preston Blier Picasso’S Demoiselles

Picasso ’s Demoiselles The Untold Origins of a Modern Masterpiece Suzanne PreSton Blier Picasso’s Demoiselles Blier_6pp.indd 1 9/23/19 1:41 PM The UnTold origins of a Modern MasTerpiece Picasso’s Demoiselles sU zanne p res T on Blie r Blier_6pp.indd 2 9/23/19 1:41 PM Picasso’s Demoiselles Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 Blier_6pp.indd 3 9/23/19 1:41 PM © 2019 Suzanne Preston Blier All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Cover designed by Drew Sisk. Text designed by Mindy Basinger Hill. Typeset in Garamond Premier Pro and The Sans byBW&A Books Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Blier, Suzanne Preston, author. Title: Picasso’s Demoiselles, the untold origins of a modern masterpiece / Suzanne Preston Blier. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018047262 (print) LCCN 2019005715 (ebook) ISBN 9781478002048 (ebook) ISBN 9781478000051 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 9781478000198 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Picasso, Pablo, 1881–1973. Demoiselles d’Avignon. | Picasso, Pablo, 1881–1973—Criticism and interpretation. | Women in art. | Prostitution in art. | Cubism—France. Classification: LCC ND553.P5 (ebook) | LCC ND553.P5 A635 2019 (print) | DDC 759.4—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047262 Cover art: (top to bottom): Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, detail, March 26, 1907. Museum of Modern Art, New York (Online Picasso Project) opp.07:001 | Anonymous artist, Adouma mask (Gabon), detail, before 1820. Musée du quai Branly, Paris. Photograph by S. P. -

Les Demoiselles D'avignon (1). Exposition, Paris, Musée Picasso, 26 Janvier-18 Avril 1988

3 Paris, Musée Picasso 26 janvier - 18 avril 1988 Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux Paris 1988 Cette exposition a été organisée par la Réunion des musées nationaux et le Musée Picasso. Elle a bénéficié du soutien d'==^=~ = L'exposition sera présentée également à Barcelone, Museu Picasso, du 10 mai au 14 juillet 1988. Couverture : Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907 (détail), New York, The Museum of Modern Art, acquis grâce au legs Lillie P. Bliss, 1939. e The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1988. ISBN 2-7118-2.160-9 (édition complète) ISBN 2-7118-2.176-5 (volume 1) @ Spadem, Paris, 1988. e Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 1988. Commissaire Hélène Seckel conservateur au Musée Picasso 1 Citée dans le livre de François Chapon, Mystère et splendeurs de Jacques Doucet, Paris, J.-C. Lattès, 1984, p. 278. Ceci à propos du manuscrit de Charmes que possédait Jacques Doucet, dont il demande à Valéry quelques lignes propres à jeter sur cette oeuvre « des clartés authentiques ». 2 Christian Zervos, « Conversation avec Picasso », Cahiers d'art, tiré à part du vol. X, n° 7-10, 1936, p. 42. 3 Archives du MoMA, Alfred Barr Papers. 4 Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet. « Le goût que nous avons pour les choses de l'esprit s'accompagne presque néces- sairement d'une curiosité passionnée des circonstances de leur formation. Plus nous chérissons quelque créature de l'art, plus nous désirons d'en connaître les ori- gines, les prémisses, et le berceau qui, malheureusement, n'est pas toujours un bocage du Paradis Terrestre ». -

The Rockies of Colorado

THE ROCKIES OF COLORADO THE ROCKIES OF COLORADO BY EVELIO ECHEVARRfA C. (Three illustrations: nos. 9- II) OLORADO has always been proud of its mountains and rightly so; it is often referred to in the Union as 'the mountain state', about 6o per cent of its area is mountainous, and contains fifty-four peaks over 14,ooo ft. and some three hundred over 13,000 ft. Further, its mountaineering history has some unique aspects. And yet, Colorado's mountains have been seldom mentioned in mountaineering journals; if in modern times they may have deserved a passing mention it has been because of a new route on Long's Peak. But on the whole, the Rockies of Colorado are almost unrecorded in the mountaineering world abroad. In this paper, an effort has been made to outline briefly the characteris tics of this area, and to review its mountaineering past; a few personal experiences are also added. The mountains of Colorado belong almost completely to the Rocky Mountain range of North America; a few outliers are sometimes mentioned as independent lesser chains, but in features and heights they are unimportant. The Rockies of Colorado are grouped into a number of ranges (see sketch-map), some of which are actually prolongations of others. Some what loosely and with some injustice to precise geography, they can be grouped into ten important sections. The state of Colorado is a perfect rectangle in shape; the Rockies enter into its western third from Wyoming, to the north, and split, then, into two parallel chains which unite in the centre of the state. -

High Country Climbs Peaks

HighHig Countryh Country Cl iClimbsmbs The San Juan Mountains surrounding Telluride are among Colorado’s most beautiful and historic peaks. This chapter records some of the Telluride region’s most classic alpine rock routes. Warning: These mountain routes are serious undertakings that should only be attempted by skilled, experienced climbs. Numerous hazards—loose rock, severe lightning storms, hard snow and ice and high altitudes—will most likely be encountered. Come Prepared: An ice axe and crampons are almost always necessary for the approach, climb or descent from these mountains. Afternoon storms are very common in the summertime, dress accordingly. Loose rock is everpre- sent, wearing a helmet should be considered. Rating Mountain Routes: Most routes in this section are rated based on the traditional Sierra Club system. Class 1 Hiking on a trail or easy cross-country Class 2 Easy scrambling using handholds Class 3 More difficult and exposed scrambling, a fall could be serious Class 4 Very exposed scrambling, a rope may be used for belaying or short-roping, a fall would be serious Class 5 Difficult rockclimbing where a rope and protection are used Route Descriptions: The routes recorded here are mostly long scrambles with countless variations possible. Detailed route descriptions are not pro- vided; good routefinding skills are therefore required. Routes described are for early to mid-summer conditions. The Climbing Season: Climbers visit these mountains all year, but the main climbing season runs from June through September. Late spring through early summer is the best time, but mid-summer is the most popular. Less snow and more loose rock can be expected in late summer. -

Campground, Mesa Verde National Park Chief Ranger Office, Mesa Verde Wilderness, a 8500 Acre Wilderness Area Located Within Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide Colorado United States Highway #160 "Cortez to Walsenburg" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Cortez, CO The city of Cortez, Colorado, a city in Montezuma County, CO. Cortez is a popular stop for tourists for its close proximity to surrounding attractions such as Mesa Verde National Park, Monument Valley, and the Four Corners. Also here is Parque De Vida, Centennial Park, Southwest Memorial Hospital and the Conquistador Golf Course. Altitude: 6191 feet 2.2 Junction State Route #145 Junction State Route #145 / County Road 27, Conquistador Golf Course, Lakeside Drive to, Denny Lake Park, Denny Lake. Altitude: 6168 feet 3.7 County Road 29 : Totten County Road 29, Totten Lake, a lake located north off United States Lake Route #160. Altitude: 6165 feet 10.3 Entrance : Mesa Verde State Highway #10, Entrance to Mesa Verde National Park, Spruce National Park Canyon Trail, Mesa Verde National Park Headquarters, Ara Morafield Campground, Mesa Verde National Park Chief Ranger Office, Mesa Verde Wilderness, a 8500 acre wilderness area located within Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. These three small and separate sections of the National Park are located on the steep north and east boundaries and serve as buffers to further protect the significant Native American sites. Unlike most wilderness areas, visitor access to Mesa Verde Wilderness is prohibited. Altitude: 6886 feet 11.3 Access : Mesa Verde RV Access to, Mesa Verde RV Resort, located just off United States Resort Highway #160. Altitude: 6844 feet 18.0 Junction State Route #184 Junction State Route #184, N Main Street. -

Exploration in British Columbia 1990

Province of l3ritish Columbia MINERAL RESOURCES DMSION Ministry of Energy, Mines and Geological Survey Branch Petroleum Resources Hon. J. Weisgerber, Minister EXPLORATION IN BRITISH COLUMBIA 1990 Part A - Overview of Exploration Activity Part B - GeologicalDescriptions of Properties British Columbia Cataloguing in Publicatlon Data Main ently undertitle: Exploration in British Columbia.- 1975- Annual. With Geology in British Columbia, ISSN 0823-1257; and, Mining in British Columbia,ISSN 0823-126, continues: Geology, exploration, and miningin British Columbia, ISSN WS-1027. 1979 published in 1983. Issuingbcdyvaries: 1975-1976, Ministvof Minesand Petroleum Resources; 1977.1965; Ministry of Encrgy, Mines and Petroleum Resources; 1986- ,Geological Survey Branch. VICTORIA ISSN 0823.2059 -Exploration in British Columbia. BRITISH COLUMBIA 1. Prospecting-British Columbia. Periodicals. 2. CANADA Geology, Economic - British Columbia. Periodicals. 1. British Columbia. Ministlyof Energy, Mines and JULY 1991 Petroleurn Resources. Ill. British Columbia. Geological Survey Branch. TN270.E96 622.1’W711 Rev. April 1987 Eskay Creek Exploration Camp 1990, looking northeast. iii FOREWORD 1990 has been a year of significant change for the mineral exploration and mining industry in British Columbiaas the exploration industryadjusted to thetermination of FlowThroughSharefinancingfor exploration. The GoldenBear mine officially reached commercial production in February, the Sullivan Pb-Zn mine reopened in November after a lengthy shutdown,and theSnip mine was closedto production at yearend. Leading developments for theyear included a new trend in metals exploration with a vigorousfocus on copper-gold-porphyry systems such as Mount Milligan, Mount Polley and GaloreCreek. In addition, continued encouraging results fromthe impressive EskayCreek area in the Golden Triangle made thisthe busiest explorationarea in the Province. -

Eagle's View of San Juan Mountains

Eagle’s View of San Juan Mountains Aerial Photographs with Mountain Descriptions of the most attractive places of Colorado’s San Juan Mountains Wojtek Rychlik Ⓒ 2014 Wojtek Rychlik, Pikes Peak Photo Published by Mother's House Publishing 6180 Lehman, Suite 104 Colorado Springs CO 80918 719-266-0437 / 800-266-0999 [email protected] www.mothershousepublishing.com ISBN 978-1-61888-085-7 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Printed by Mother’s House Publishing, Colorado Springs, CO, U.S.A. Wojtek Rychlik www.PikesPeakPhoto.com Title page photo: Lizard Head and Sunshine Mountain southwest of Telluride. Front cover photo: Mount Sneffels and Yankee Boy Basin viewed from west. Acknowledgement 1. Aerial photography was made possible thanks to the courtesy of Jack Wojdyla, owner and pilot of Cessna 182S airplane. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Section NE: The Northeast, La Garita Mountains and Mountains East of Hwy 149 5 San Luis Peak 13 3. Section N: North San Juan Mountains; Northeast of Silverton & West of Lake City 21 Uncompahgre & Wetterhorn Peaks 24 Redcloud & Sunshine Peaks 35 Handies Peak 41 4. Section NW: The Northwest, Mount Sneffels and Lizard Head Wildernesses 59 Mount Sneffels 69 Wilson & El Diente Peaks, Mount Wilson 75 5. Section SW: The Southwest, Mountains West of Animas River and South of Ophir 93 6. Section S: South San Juan Mountains, between Animas and Piedra Rivers 108 Mount Eolus & North Eolus 126 Windom, Sunlight Peaks & Sunlight Spire 137 7. Section SE: The Southeast, Mountains East of Trout Creek and South of Rio Grande 165 9. -

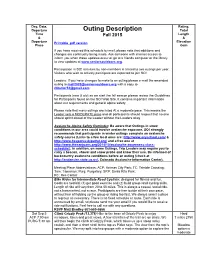

Outing Description

Day, Date, Rating, Departure Outing Description Total Time Fall 2015 Length & & Departure Printable .pdf version Elevation Place Gain If you have received this schedule by mail, please note that additions and changes are continually being made. Ask someone with internet access to inform you when these updates occur or go to a friends computer or the library to view updates at www.seniorsoutdoors.org. Participation in SO! activities by non-members is limited to two outings per year. Visitors who wish to actively participate are expected to join SO! Leaders: If you have changes to make to an outing please e-mail the amended outing to [email protected] with a copy to [email protected] Participants (new & old) as we start the fall season please review the Guidelines for Participants found on the SO! Web Site. It contains important information about our requirements and general alpine safety. Please note that many outings are listed At a moderate pace. This means the Leader sets a MODERATE pace and all participants should respect that no one should sprint ahead of the Leader without the Leaders okay. Avalanche Alpine Safety Reminder: Be aware that Outings in snow conditions in our area could involve avalanche exposure. SO! strongly recommends that participants in winter outings complete an avalanche safety course (Links to a few local ones are: http://www.avyschool.com/ & http://www.hesperusskipatrol.org/ and a free one at http://www.thesanjuans.org/2014/10/avalanche-awareness-class- schedule/). In addition, on some Outings, Trip Leaders may require you to carry a beacon, shovel and snow probe and know their use. -

Newsletter of the Colorado Native Plant Society

Aquilegia Newsletter of the Colorado Native Plant Society IN THIS ISSUE Forty Years of Progress in Pollination Biology Return of the Native: Colorado Natives in Horticulture Climate Change and Columbines The Ute Learning and Ethnobotany Garden Volume 41 No.1 Winter 2017 The Urban Prairies Project Book Reviews Aquilegia Volume 41 No. 1 Winter 2017 1 Aquilegia: Newsletter of the Colorado Native Plant Society Dedicated to furthering the knowledge, appreciation, and conservation of native plants and habitats of Colorado through education, stewardship, and advocacy AQUILEGIA: Newsletter of the Colorado Native Plant Society Inside this issue Aquilegia Vol . 41 No . 1 Winter 2017 Columns ISSN 2161-7317 (Online) - ISSN 2162-0865 (Print) Copyright CoNPS © 2017 News & Announcements . 4 Aquilegia is the newsletter of the Colorado Native Plant Letter to the Editor . 9 Society . Members receive four regular issues per year (Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter) plus a special issue for the Workshops . 10 Society Annual Conference held in the Fall . At times, Chapter Programs & Field Trips . 11 issues may be combined . All contributions are subject to editing for brevity, grammar, and consistency, with final Conservation Corner: Conserving Colorado’s Native Plants . 23 approval of substantive changes by the author . Articles Garden Natives . 30 from Aquilegia may be used by other native plant societ- Book Reviews . 31 ies or non-profit groups, if fully cited to the author and attributed to Aquilegia . The deadline for the Spring 2017 Articles issue is March 15 and for the Summer issue is June 15 . 40 Years of Progress in Pollination Biology . 14 Announcements, news, articles, book reviews, poems, botanical illustrations, photographs, and other contribu- Return of the Native: Colorado Native Plants in Horticulture . -

Peak and Route List (Routes Grade IV Or Higher in Red; Attempts Not Listed)

Peak and Route List (routes grade IV or higher in red; attempts not listed) International Barbeau Peak West ridge Ellesmere Island, Canadian Arctic Peak N. of Barbeau SE ridge? Ellesmere Island Wilson's Wall SW face, first ascent Baffin Island, Canadian Arctic (VI, 5.11 A4) Dhalagiri VII (Putha Hiunchuli) East ridge Dhualagiri Range, Nepal Turka Himal East ridge, first ascent? Dhualagiri Range, Nepal Cerro Aconcagua False Polish Glacier Andes, Argentina Cerro Las Menas trail Honduras (high point) Mt. Arrowsmith reg. couloir Vancouver Island, Canada Lowell Peak South Face, first ascent St. Elias Range, Canada Mt. Alverstone NE 5 North Ridge, first ascent St. Elias Range, Canada Peak 12,792 South Ridge Altai Mountains, Russian Siberia Alaska Denali West Buttress Alaska Range Mt. Marathon trail Kenai Peninsula Institute Peak SW face, winter ascent Eastern Alaska Range (Delta Range) Mt. Prindle Giradelli (III 5.9) White Mountains, Interior Gunnysack Creek peak W side Eastern Alaska Range (Delta Range) Chena Dome (2x) trail Chena River State Rec. Area Falsoola Peak north col Endicott Mountains, Brooks Range Green Steps (Keystone Canyon) (IV, WI 4-5) Valdez ice Silvertip Peak west side (day push) Eastern Alaska Range (Delta Range) Pinnell Mountain trail Porcupine Dome trail Mt. Sukakpak Reg. Route Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Unnamed peak East ridge South of Black Rapids Glacier, (Eastern Alaska Range) The Moose's Tooth Ham and Eggs (V, AI5 M4) Central Alaska Range Arizona Humphreys Peak (state highpoint) Weatherford Canyon marathon California: Yosemite only: El Capitan Zodiac (2x) Tangerine Trip The Nose Salathe Wall Zenyatta Mondatta Half Dome NW face, Regular Route (2x, incl.