PS Signpost Belas Knap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Does English Heritage Need My Support? English Heritage Cares for Over 400 Historic Buildings and Places Which Are Enjoyed by Millions Each Year

Belas Knap Long Barrow Monitor Volunteer Role Description Why does English Heritage need my support? English Heritage cares for over 400 historic buildings and places which are enjoyed by millions each year. Within our portfolio there are 103 sites in the west of England which are free to enter and are unstaffed; Belas Knap Long Barrow is one of these. It is a particularly fine example of a neolithic long barrow, with a false entrance and side chambers. Excavated in 1863 and 1865, the remains of 31 people were found in the chambers. The barrow has since been restored. As a site monitor volunteer you will play an important role in looking after Belas Knap Long Barrow and ensuring it is safe and well presented for our many visitors. Whether that’s checking for issues affecting the structure, the wider landscape or the route into and out of the site, you will help us to better understand and care for this site, by reporting issues and helping to maintain the site’s presentation. How much time will I be expected to give? Though regular visits are important, the frequency can be agreed between us. It may be weekly or monthly depending on your availability and the times can be flexible to suit you. Where will I be based? The role will be based at Belas Knap Long Barrow, Winchcombe, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, GL54 5AL What will I be doing? . Providing feedback to the Free Sites West Team, about any damage to the structure or any problems you find on or on the route up to the site. -

Hazleton Revisited by Alan Saville 2010, Vol

From the Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Anatomising an Archaeological Project – Hazleton Revisited by Alan Saville 2010, Vol. 128, 9-27 © The Society and the Author(s) Trans. Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 128 (2010), 9–27 Anatomizing an Archaeological Project – Hazleton Revisited By ALAN SAVILLE Presidential Address delivered at Gambier Parry Hall, Highnam, 27 March 2010 Introduction In revisiting the Hazleton excavation project my address has several objectives, most of which I can cast as a series of questions which will form the headings to the following sections into which the talk is subdivided. Firstly, however, I need to provide a brief summary of the Hazleton North excavation. Hazleton was an archaeological excavation project, the fieldwork phase of which was spread over the four years 1979–1982. Hazleton is a small Cotswold village close to the main A40 road, just to the north-west of Northleach and of considerable historical interest, as recently recorded in the Society’s Transactions (Dyer and Aldred 2009). The focus of the excavation was a Neolithic long cairn – known as the Hazleton North barrow (NGR SP 0727 1889) – lying just to the north of the village, an example of a so-called Cotswold-Severn tomb of which there are several well- known Gloucestershire examples, such as Belas Knap and Hetty Pegler’s Tump. These tombs belong to some of the very earliest agricultural communities living in the Cotswolds, dating to almost 6000 years ago, and are a truly remarkable survival of ancient architecture. Barrow Ground Field at Hazleton had two closely sited long cairns, Hazleton North and Hazleton South (Fig. -

Events, Processes and Changing Worldviews from the Thirty-Eighth to the Thirty-Fourth Centuries Cal

Article Building for the Dead: Events, Processes and Changing Worldviews from the Thirty-eighth to the Thirty- fourth Centuries cal. BC in Southern Britain Wysocki, Michael Peter, Barclay, A, Bayliss, A, Whittle, A and Sculting, R Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/10756/ Wysocki, Michael Peter, Barclay, A, Bayliss, A, Whittle, A and Sculting, R (2007) Building for the Dead: Events, Processes and Changing Worldviews from the Thirty-eighth to the Thirty-fourth Centuries cal. BC in Southern Britain. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 17 (S1). pp. 123-147. It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0959774307000200 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/policies/ CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk Building for the Dead Building for the Dead: Events, Processes and Changing Worldviews from the Thirty-eighth to the Thirty-fourth Centuries cal. bc in Southern Britain Alasdair Whittle, Alistair Barclay, Alex Bayliss, Lesley McFadyen, Rick Schulting & Michael Wysocki Our final paper in this series reasserts the importance of sequence. -

Does the Archaeoastronomic Record of the Cotswold-Severn Region Reflect Evidence of a Transition from Lunar to Solar Alignment?

Does the archaeoastronomic record of the Cotswold-Severn region reflect evidence of a transition from lunar to solar alignment? Pamela Armstrong Student Number: 28002067 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of M.A. in Cultural Astronomy and Astrology University of Wales Trinity Saint David 2014 1 Master’s Degrees by Examination and Dissertation Declaration Form. 1. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Name. Pamela Armstrong........………………………………………………... Date 20th January 2014...........................................……………………... 2. This dissertation is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of ……………………………………………………………….................................. Name…M A in Cultural Astronomy and Astrology..........................…………. Date 20th January 2014................................……….…………..…………... 3. This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Name…Pamela Armstrong.....................…………………….………………. Date: 20th January 2014.......……………………...………………………. 4. I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying, inter- library loan, and for deposit in the University’s digital repository Name…..Pamela Armstrong.............…………………………………………. Date……20th January 2014..........……………….…………………………….. Supervisor’s -

Cleveland Museum of Natural History UK Tour September 2018

Cleveland Museum of Natural History UK Tour September 2018 MAP OF UK & IRELAND A&K Europe Ltd. St. George’s House, Ambrose Street, Cheltenham, Gloucestershire GL50 3LG UK, Tel: +44 (0) 1242 547 700, Fax: +44 (0) 1242 547 707, Email: [email protected] Page 2 of 13 Touring Ancient Britain What was life like in Ancient Britain? Who built Stonehenge and the other great Megaliths of England? What happened after the Roman invasion? Join Dr. Brian Redmond, Head of Archaeology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History to visit the UK’s most prolific Neolithic to Roman archaeology. Arriving into London on Monday, September 10, 2018 and departing Glasgow on Thursday, September 20, 2018. During this 10 night trip you will visit the world famous British Museum in London, see the UNESCO World Heritage Neolithic sites of Stonehenge and Avebury along with the Nympsfield Long Barrow and the Roman sites of the Fishbourne Roman Palace, Chedworth Roman Villa and Hadrian’s Wall. ‘AT A GLANCE’ ITINERARY DATE DAY DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION MEALS* Mon 10 Sep 2018 Arrive London The Bailey’s Hotel D Tue 11 Sep 2018 London The Bailey’s Hotel B Wed 12 Sep 2018 London to Winchester via Winchester Royal Hotel B, L Fishbourne Thu 13 Sep 2018 Winchester to Bath via Stonehenge Francis Hotel – MGallery by Sofitel B, L & Avebury Fri 14 Sep 2018 Bath Francis Hotel – MGallery by Sofitel B, D Sat 15 Sep 2018 Bath to Cheltenham via Chedworth The Queen’s Hotel – MGallery by B, L Roman Villa Sofitel Sun 16 Sep 2018 Cheltenham The Queen’s Hotel – MGallery by B, D Sofitel Mon 17 Sep 2018 Cheltenham to York The Principal York Hotel B Tue 18 Sep 2018 York The Principal York Hotel B, D Wed 19 Sep 2018 York to Glasgow Malmaison Hotel Glasgow B, L, D Thu 20 Sep 2018 Depart Glasgow B *B = Breakfast, L = Lunch, D = Dinner A&K Europe Ltd. -

4. Winchcombe and Belas Knap

Cotswold Way Circular Walks 4. Winchcombe and Belas Knap This scenic and interesting the other side. Continue to follow little walk takes you from the the signs along the field boundaries Winchcombe B4078 delightfully unspoilt town of until you reach Corndean Lane. Start Winchcombe, along Cotswold Watching for traffic, turn left 1 Way routes old and new, and head up the lane until the Almsbury 2 and up to one of the area’s Cotswold Way branches off Farm most intriguing ancient through a wide gate on the right. monuments, Belas Knap - Carry on up this access road, past y Wa A combination of history the cricket ground on the right, old 7 and scenery that will leave until a fingerpost guides you B4632 you eager to discover more through a kissing gate on your left. Cotsw of the National Trail and Head on up through the middle the inspirational landscape of the rolling green fields towards through which it runs. the woods at the top of the hill. Chipping Campden Wadfield 3 The kissing gate at the top Cor Distance: Grove is an excellent spot to rest awhile Winchcombe ndean Lane 5¼ miles and take in the wonderful views (Shorter route 3½ miles) over the town behind you. Once Duration: you’ve caught your breath, go 3 - 4 hrs (Shorter route: 2 - 3 hrs) through the gate and leave the Difficulty: Cotswold Way to head right, Bath Moderate, some steep sections up the road between the trees. and stiles (If you don’t fancy the last climb up Wadfield to Belas Knap, head along the road 3 6 Farm Public transport: 5 straight ahead to take up the route No. -

4. Winchcombe and Belas Knap

Cotswold Way Circular Walks 1 Mile 4. Winchcombe and Belas Knap This scenic and interesting Watching for traffic, turn left little walk takes you from the and head up the lane until the Winchcombe B4078 delightfully unspoilt town of Cotswold Way branches off Start Winchcombe, along Cotswold through a wide gate on the right. 1 Follow this access road, past the Way routes old and new, Almsbury and up to one of the area’s cricket ground on the right, until 2 Farm most intriguing ancient a fingerpost guides you through a kissing gate on your left. Head monuments, Belas Knap - y A combination of history on up through the middle of the Wa old 7 and scenery that will leave rolling green fields towards the B4632 you eager to discover more woods at the top of the hill. Cotsw of the National Trail and 3 The kissing gate at the top is the inspirational landscape an excellent spot to rest awhile and through which it runs. take in the wonderful views over Chipping Campden the town behind you. Once you’ve Wadfield Distance: Cor Grove 5¼ miles caught your breath, go through the Winchcombe ndean Lane (Shorter route 3½ miles) gate and leave the Cotswold Way to head right up the road. (If you Duration: don’t fancy the last climb up to Belas 3 - 4 hrs (Shorter route: 2 - 3 hrs) Knap, follow the Cotswold Way path through the woods and cross over the Difficulty: Bath Moderate, some steep sections stile to take up the route on the road and stiles at point 5). -

MEGALITH BUILDERS of WESTERN EUROPE by the Same Author

GOVERNMENT OE INDIA DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY CENTRAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL LIBRARY Class. Call No.. _9AS. 4 P_Parc .A. 79. THE MEGALITH BUILDERS OF WESTERN EUROPE By the same author I942. TUP. THREE ACES I9JO. THE PREHISTORIC CHAMBER TOMBS OP ENGLAND AND WALES X9J0. A HUNDRED TEARS OP ARCHAEOLOGY 1951. (With S. Piggott) A PICTURP. BOOK OP ANCIENT BRITISH ART X9J5. LASCAUX AND CARNAC 1956. (With T. G. E. Powell) barclodud t gawres The Megalith Builders of Western Europe GLYN DANIEL FELLOW OF ST JOHN’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, AND LECTURER IN ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITY f j.. HUTCHINSON OF LONDON HUTCHINSON & CO. {Publishers) LTD 178-102 Great Port land Street, Lontlon, W.\ London Melbourne Sydney Auckland Bombay Toronto Johannesburg New York * First P u bli sited 1958 This book, commissioned for the Archae¬ ology Section of the Hutchinson University Library (Editor Professor C. F. C. I lawkes), is first being issued in this larger format with additional half-tone illustrations LI»’ziiz-b;. Aco. "No • ^ . 1)11,0 " C\, . Call No . <£) G. E. Daniel 1958 This book, has been set in Garamond type face. It has been printed in Great Britain by Tonbridge Printers Ltd, Tonbridge, Kent, on Antique Wove paper and bound by Taylor Garnett Evans & Co., Ltd., in Watford, Herts For ELSIE CLIFFORD Notgrovc - Nympsfield - Rodmarton CONTENTS List of Plates 9 List of Figures 10 Preface 11 1 Megalithic Tombs- and Temples 13 2 The Prehistoric Collective Tombs of Western Europe 29 3 Northern Europe and Iberia 5 2 4 The West Mediterranean 76 j France * 89 6 The Bridsh Isles 105 7 Conclusion 120 Books for Further Reading 13 3 Index 137 LIST OF PLATES BETWEEN PAGES 64 & 65 I A hunched in Holland and a Portuguese an/a. -

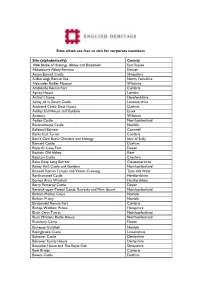

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and -

Grismond's Tower, Cirencester, and the Rise of Springhead Super-Mounds in the Cotswolds and Beyond

Trans. Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 132 (2014), 11–27 Grismond’s Tower, Cirencester, and the Rise of Springhead Super-mounds in the Cotswolds and Beyond By TIMOTHY DARVILL Presidential Address delivered at Gambier Parry Hall, Highnam, 29 March 2014 Here in Gloucestershire we are very lucky to have some of the best preserved and most interesting archaeological remains in north-west Europe. Belas Knap long barrow, Uley Bury hillfort, Chedworth Roman villa, the Saxon churches of the Coln valley and our wonderful castles (most still occupied) represent just a few of the highlights; and, of course, there are many more. Some are not so visible and not as well loved as those just mentioned, and some fade in and out of archaeological consciousness as interest shifts between different aspects of our past. It is one of these monuments with a slightly chequered history that I would like to use as the centrepiece of this lecture. It is the great domed mound nowadays known as Grismond’s Tower just inside the walls of Cirencester Park beside Tetbury Road on the west side of the town. This tree-covered hill, long regarded as a round barrow, is about 30 m in diameter and stands about 4 m high (Fig. 1). As such, it is one of the largest surviving round barrows on the Gloucestershire Cotswolds, yet it is little known. During our Society’s visit to Cirencester for the President’s Meeting in October 2013 we were able to visit and inspect Grismond’s Tower through the kindness of Allen Bathurst, 9th Earl Bathurst, starting outside the very fine icehouse built into the mound in the 1780s (Fig. -

Winchcombe to Belas Knap Walk Church K C

Viaduct St. Andrew’s Church Toddington Cricket New Pavilion B4077 To w n Stanway House St. Peter’s Church GWR Stanway Station Stanway Watermill y a W e n B4078 r u o b Is 0 0.25 0.5 mile 0 0.5 km R i v e r St. George’s Isb Church ou rn e Didbrook Wood Stanway Royal Oak Gretton B4362 Hailes Hailes Church Stanley Hailes Pontlarge Wood Hailes Greet River Isbourne Abbey Prescott Pottery Hayles ay Fruit Farm ay Cups Hill W W Stanley old ld GWR w o ts w Hill Wood o s C t Station o Climb C T Manor i Glos Way rl e y Farm B a ro o W k ne Petrol r ou Station b Winchcombe Walkers are Welcome Is Farmcote www.winchcombewelcomeswalkers.com Herbs Langley Hill 275m Farmcote WINCHCOMBE Langley Hill Farm Farmcote Walk 5 Winchcombe to Belas Knap walk Church k c Stancombe a r Farm T n This walk offers both a linear and e Ha d r p ve circular walk with some ascent. ys m La a Heading out from Winchcombe along ne Tourist Information Centre C Nottingham Hill the Cotswold Way to Belas Knap before S al W Winchcombe t in ch 279m Rushbury St. Peters Church W co returning via the Sudeley Valley. Lovely mbe House W a Way inchcom y views of the town, Sudeley Castle and be Way the surrounding countryside. Distance: 5.5 miles/ 8.8 km Lodge St Kenelm’s ay Duration 2 - 2.75 hours W Longwood d Well ol Farm sw Sudeley Hill Dryfield Difficulty: Moderate but some steep ot Langley 32 C Farm Farm sections Brook B46 e A n Sudeley r Start/finish: Back Lane car park, u o Castle b Apple Tree Winchcombe (Grid Ref: SP 023/284) Is . -

Early Prehistory Timothy Darvill

Early Prehistory Timothy Darvill INTRODUCTION Twenty-five years is a long time in the study of prehistory. Since the first Archaeology in Glouce stershire conference in September 1979 there have been numerous excavations, surveys, chance finds, reviews of earlier work, and the publication of investigations carried out in previous decades. Results from some of this work were incorporated in the conference's published papers which appeared in 1984 (Saville 1984), and there was another opportunity to update these accounts in a volume on prehistory for the County Library Service published three years later (Darvill 1987). In drawing together this overview covering the quarter century of archaeological· endeavour between 1979 and 2004 attention is focused on three questions. What has been done over the last 25 years? What has been found? And what do the results of these investigations and discoveries mean for our understanding of early prehistory in Gloucestershire? Chronologically, the period covered spans the earliest colonization of the area by human communities during the late Pleistocene through to about 1000 BC, the beginning of the late Bronze Age in the conventional terminology of the expanded Three-Age System. Although, geographically, the 1979 conference confined its view to the then 'new' county of Gloucestershire established in 1974 (see Aston and lies 1987 for a comparable overview of Avon) subsequent changes to local government administrative areas now make it appropriate to return to something appro aching the historic counties of Bristol and Gloucestershire. These embrace the local government districts of Cotswold, Stroud, Tewkesbury, Forest of Dean, Cheltenham, and Gloucester, and the unitary authorities of Bristol (north of the river Avon) and South Gloucestershire.