The Irresistible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benjamin Hoffmann Academic Positions Education

Curriculum Vitae – Benjamin Hoffmann 1 BENJAMIN HOFFMANN Associate Professor The Ohio State University Department of French and Italian Columbus OH, 43210-1340 [email protected] ACADEMIC POSITIONS Associate Professor of Early Modern French Studies 2019-present The Ohio State University Assistant Professor of Early Modern French Studies 2015-2019 The Ohio State University Visiting Lecturer July 2011 École Normale supérieure – Summer School. Lecturer 2009-2010 Institut Supérieur d’Interprétariat et de Traduction (Paris). Language Assistant 2008-2009 Amherst College (MA). EDUCATION Yale University, New Haven, CT 2010-2015 PhD, Department of French (2015) Dissertation: Posthumous America: Literary Reinventions of America at the Turn of the Eighteenth-century. Supervisors: Thomas M. Kavanagh and Christopher L. Miller. M.A. and M.Phil. (2012) École Normale Supérieure, Paris 2006-2010 Diplômé de l’École Normale Supérieure. Primary Specialty: Modern Literature; Secondary Specialty: Philosophy. Supervisors: Déborah Lévy-Bertherat (Department of Literature and Languages); Francis Wolff (Department of Philosophy). Université Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV), Paris 2006-2008 Master II de Littérature française. Supervisors: Pierre Frantz and Michel Delon. Thesis: « Le thème du voyage dans la création romanesque de Sade ». Grade: 18/20 Curriculum Vitae – Benjamin Hoffmann 2 Master I de Littérature française. Supervisor: Pierre Frantz. Thesis: « Bonheur et Liberté dans l’Histoire de ma vie de Giacomo Casanova ». Grade: 17/20. Université Bordeaux-III, Talence 2003-2006 Licence de Lettres modernes. Licence de Philosophie. Lycée Montesquieu, Bordeaux 2000-2003 Baccalauréat littéraire. AWARDS AND FELLOWSHIPS - Havens Faculty Research Prize. The Ohio State University, Department of French and Italian. Award amount: $1000 (Fall 2019). - Faculty Special Assignment. -

Géraldine Crahay a Thesis Submitted in Fulfilments of the Requirements For

‘ON AURAIT PENSÉ QUE LA NATURE S’ÉTAIT TROMPÉE EN LEUR DONNANT LEURS SEXES’: MASCULINE MALAISE, GENDER INDETERMINACY AND SEXUAL AMBIGUITY IN JULY MONARCHY NARRATIVES Géraldine Crahay A thesis submitted in fulfilments of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in French Studies Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures June 2015 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... ix Declaration and Consent ........................................................................................................... xi Introduction: Masculine Ambiguities during the July Monarchy (1830‒48) ............................ 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Framework: Masculinities Studies and the ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity ............................. 4 Literature Overview: Masculinity in the Nineteenth Century ......................................................... 9 Differences between Masculinité and Virilité ............................................................................... 13 Masculinity during the July Monarchy ......................................................................................... 16 A Model of Masculinity: -

Intermedialtranslation As Circulation

Journal of World Literature 5 (2020) 568–586 brill.com/jwl Intermedial Translation as Circulation Chu Tien-wen, Taiwan New Cinema, and Taiwan Literature Jessica Siu-yin Yeung soas University of London, London, UK [email protected] Abstract We generally believe that literature first circulates nationally and then scales up through translation and reception at an international level. In contrast, I argue that Taiwan literature first attained international acclaim through intermedial translation during the New Cinema period (1982–90) and was only then subsequently recognized nationally. These intermedial translations included not only adaptations of literature for film, but also collaborations between authors who acted as screenwriters and film- makers. The films resulting from these collaborations repositioned Taiwan as a mul- tilingual, multicultural and democratic nation. These shifts in media facilitated the circulation of these new narratives. Filmmakers could circumvent censorship at home and reach international audiences at Western film festivals. The international success ensured the wide circulation of these narratives in Taiwan. Keywords Taiwan – screenplay – film – allegory – cultural policy 1 Introduction We normally think of literature as circulating beyond the context in which it is written when it obtains national renown, which subsequently leads to interna- tional recognition through translation. In this article, I argue that the contem- porary Taiwanese writer, Chu Tien-wen (b. 1956)’s short stories and screenplays first attained international acclaim through the mode of intermedial transla- tion during the New Cinema period (1982–90) before they gained recognition © jessica siu-yin yeung, 2020 | doi:10.1163/24056480-00504005 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc by 4.0Downloaded license. -

Phd Thesis the Anglo-American Reception of Georges Bataille

1 Eugene John Brennan PhD thesis The Anglo-American Reception of Georges Bataille: Readings in Theory and Popular Culture University of London Institute in Paris 2 I, Eugene John Brennan, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: Eugene Brennan Date: 3 Acknowledgements This thesis was written with the support of the University of London Institute in Paris (ULIP). Thanks to Dr. Anna-Louis Milne and Professor Andrew Hussey for their supervision at different stages of the project. A special thanks to ULIP Librarian Erica Burnham, as well as Claire Miller and the ULIP administrative staff. Thanks to my postgraduate colleagues Russell Williams, Katie Tidmash and Alastair Hemmens for their support and comradery, as well as my colleagues at Université Paris 13. I would also like to thank Karl Whitney. This thesis was written with the invaluable encouragement and support of my family. Thanks to my parents, Eugene and Bernadette Brennan, as well as Aoife and Tony. 4 Thesis abstract The work of Georges Bataille is marked by extreme paradoxes, resistance to systemization, and conscious subversion of authorship. The inherent contradictions and interdisciplinary scope of his work have given rise to many different versions of ‘Bataille’. However one common feature to the many different readings is his status as a marginal figure, whose work is used to challenge existing intellectual orthodoxies. This thesis thus examines the reception of Bataille in the Anglophone world by focusing on how the marginality of his work has been interpreted within a number of key intellectual scenes. -

A. Affiliations, 3 Distinctions B

Doing Experience – Marvel Heroics Style 0. Consider each data file to have, at least, the following for free: a. Affiliations, 3 Distinctions b. One power set, 2 die at d6, one sfx and one limit(assume extra limits are added, no t changed) c. 2 specialities at d8 d. Milestones 1. Using normal XP expenditure rules, calculate how much EXP it would take to make that character. 2. For a custom character within a group of pre-made files, add up all the EXP spent by each character (either before or after the beginning of play) 3. Divide it by the number of players – this will give you your mean. 4. After applying the rule of 0 to the custom character, give them that much EXP to spend on making their character. Example Armour Ignore Affiliations and Distinctions. Power set o Two powers of d10 – 40 EXP(10 for d8, 10 for d10 x2) o 3 sfx – 30 EXP (2 new Sfx =15 exp) o 2 Limits – 5 EXP (1 new limit=5 exp) Specialities o 3 at Expert – 15exp(2 free, one at expert purchased) Total =90 exp Keep in mind If somebody actually has less than rule 0 for in power sets or specialities a reduction in XP cost is applied. If a sheet says X+Y, X is the first and Y the second power set on the sheet respectively. This isn’t entirely indicative of effectiveness. These are just numbers. Means are rounded to nearest multiple of 5, with the actual number (0dp) in brackets. It’s hard to find groups of four with identical XP costs – a range of +-10 should suffice. -

Marvel-Phile: Über-Grim-And-Gritty EXTREME Edition!

10 MAR 2018 1 Marvel-Phile: Über-Grim-and-Gritty EXTREME Edition! It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It 90s, but you’d be wrong. Then we have Nightwatch, a was a dark time for the Republic. In short, it was...the bald-faced ripoff of Todd MacFarlane’s more ‘90s. The 1990s were an odd time for comic books. A successful Spawn. Next, we have Necromancer… the group of comic book artists, including the likes of Jim Dr. Strange of Counter-Earth. And best for last, Lee and hate-favorite Rob Liefield, splintered off from there’s Adam X the X-TREME! Oh dear Lord -- is there Marvel Comics to start their own little company called anything more 90s than this guy? With his backwards Image. True to its name, Image Comics featured comic baseball cap, combustible blood, a costume seemingly books light on story, heavy on big, flashy art (often made of blades, and a title that features not one but either badly drawn or heavily stylized, depending on TWO “X”s, this guy that was teased as the (thankfully who you ask), and a grim and gritty aesthetic that retconned) “third Summers brother” is literally seemed to take all the wrong lessons from renowned everything about the 90s in comics, all rolled into one. works such as Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns. Don’t get me wrong, there were a few gems in the It wasn’t long until the Big Two and other publishers 1990s. Some of my favorite indie books were made hopped on the bandwagon, which was fueled by during that time. -

Vol. 84 Wednesday, No. 137 July 17, 2019 Pages 34051–34254

Vol. 84 Wednesday, No. 137 July 17, 2019 Pages 34051–34254 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Sep 11 2014 18:39 Jul 16, 2019 Jkt 247001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\17JYWS.LOC 17JYWS jbell on DSK3GLQ082PROD with FRONTWS II Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 137 / Wednesday, July 17, 2019 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) Subscriptions: and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Government Publishing Office, is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general (Toll-Free) applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published FEDERAL AGENCIES by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public Subscriptions: interest. Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions: Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Email [email protected] issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

Giacomo Casanova

Giacomo Casanova Sergio Mejía Macía Con recurso a la película de Federico Fellini Fellini’s Casanova y a la autobiografía del veneciano, Histoire de ma vie Este texto teatral sobre la vida de Giacomo Casanova (17251798) toma préstamos, sin pudor ni economía, de la película Fellini’s Ca sanova, producida por Alberto Grimaldi y Twentieth Century Fox en 1976, sobre guión escrito a cuatro manos por Bernardino Zapponi y Federico Fellini y dirigida por el último. Consulté sin método la autobiografía de Casanova, escrita en francés con el título Histoire de ma vie y publicada por primera vez en Leipzig entre 1822 y 1824, en traducción alemana. Utilicé la edición francesa establecida por Francis Lacassin, publicada por la casa parisina de Robert Lafront en 1993. Las tres primeras escenas corresponden a episodios de la Histoire de ma vie no incluidos en la película de Fellini. Las restantes siete son interpretaciones libres de episodios tratados por Fellini, todos ellos tergiversados por una lectura muy personal de la Histoire de ma vie, obra a su vez muy personal. Se incluyen traducciones libres,de fragmentos de los siguientes poemas: Ariosto, Orlando Furioso, Canto Segundo, primera Estanza; Canto Cuarto, sexta Estanza Torcuato Tasso, Noches 36 Artes, La Revista, Nº. 12 Volumen 6/ juliodiciembre, 2006 Personajes Casanova viejo Henriette Una flaca alta La monja de Murano Casanova joven Cinco cortesanos (tres Una pelirroja baja Una condesa mujeres y dos hombres) Casanova niño Dos prostitutas Cinco monjas Madame d’Urfé Marzia, la abuela Una -

The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby Prose 1925 New York, USA F. Scott Fitzgerald Gone with the Wind Prose 1936 New York, USA Margaret Mitchell Pride and Prejudice Prose 1813 London, England Jane Austen Frankenstein Prose 1818 London, England Mary Shelley Waverley, or Tis Sixty Years Since Prose 1814 Edinburgh, Scotland Sir Walter Scott À la recherche du temps perdu Prose 1913 Paris, France Marcel Proust Myortvye dushi Prose 1842 St. Petersburg, Russia Nikolay Vasilyevich Gogol Die Blechtrommel Prose 1859 Darmstadt, Germany Gunter Grass Simplicius Simplicissimus Prose 1968 Nuremberg, Germany Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha Prose 1605 Valencia, Spain Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra Pepita Jiménez Prose 1874 Madrid, Spain Juan Valera Il Gattopardo Prose 1958 Milan, Italy Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa Jacques Casanova de Seingalt Vénitien, Histoire de ma vie Prose 1797 Brussels, Belgium Giacomo Casanova La Sofonisba, Tragedia, Di Nuovo con Somma Diligenza Corretta Ristampata Play 1594 Venice, Italy Gian Giorgio Trissino Libro de Calixto y Melibea y de la puta vieja Celestina Play 1502 Sevilla, Spain Fernando de Rojas Ermordete Majestät, oder Carolus Stuardus Play 1657 Breslau (Wrocław), Poland Andreas Gryphius Mr William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies Play 1623 London, England William Shakespeare Il servitore di due padroni Play 1746 Venice, Italy Carlo Goldoni El sí de las Niñas la Comedia Nueva o El café Poesías Play 1801 Madrid, Spain Leandro Fernández de Moratín Penthesilea Erläuterungen -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Apr COF C1:Customer 3/8/2012 3:24 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18APR 2012 APR E E COMIC H H T T SHOP’S CATALOG IFC Darkhorse Drusilla:Layout 1 3/8/2012 12:24 PM Page 1 COF Gem Page April:gem page v18n1.qxd 3/8/2012 11:16 AM Page 1 THE MASSIVE #1 STAR WARS: KNIGHT DARK HORSE COMICS ERRANT— ESCAPE #1 (OF 5) DARK HORSE COMICS BEFORE WATCHMEN: MINUTEMEN #1 DC COMICS MARS ATTACKS #1 IDW PUBLISHING AMERICAN VAMPIRE: LORD OF NIGHTMARES #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO PLANETOID #1 IMAGE COMICS SPAWN #220 SPIDER-MEN #1 IMAGE COMICS MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 3/8/2012 11:40 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strawberry Shortcake Volume 2 #1 G APE ENTERTAINMENT The Art of Betty and Veronica HC G ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Bleeding Cool Magazine #0 G BLEEDING COOL 1 Radioactive Man: The Radioactive Repository HC G BONGO COMICS Prophecy #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Pantha #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 Power Rangers Super Samurai Volume 1: Memory Short G NBM/PAPERCUTZ Bad Medicine #1 G ONI PRESS Atomic Robo and the Flying She-Devils of the Pacific #1 G RED 5 COMICS Alien: The Illustrated Story Artist‘s Edition HC G TITAN BOOKS Alien: The Illustrated Story TP G TITAN BOOKS The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen III: Century #3: 2009 G TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Harbinger #1 G VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC Winx Club Volume 1 GN G VIZ MEDIA BOOKS & MAGAZINES Flesk Prime HC G ART BOOKS DC Chess Figurine Collection Magazine Special #1: Batman and The Joker G COMICS Amazing Spider-Man Kit G COMICS Superman: The High Flying History of America‘s Most Enduring -

Reading Houellebecq and His Fictions

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions Sterling Kouri University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Kouri, Sterling, "Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3140. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3140 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3140 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reading Houellebecq And His Fictions Abstract This dissertation explores the role of the author in literary criticism through the polarizing protagonist of contemporary French literature, Michel Houellebecq, whose novels have been both consecrated by France’s most prestigious literary prizes and mired in controversies. The polemics defining Houellebecq’s literary career fundamentally concern the blurring of lines between the author’s provocative public persona and his work. Amateur and professional readers alike often assimilate the public author, the implied author and his characters, disregarding the inherent heteroglossia of the novel and reducing Houellebecq’s works to thesis novels necessarily expressing the private opinions and prejudices of the author. This thesis explores an alternative approach to Houellebecq and his novels. Rather than employing the author’s public figure to read his novels, I proceed in precisely the opposite -

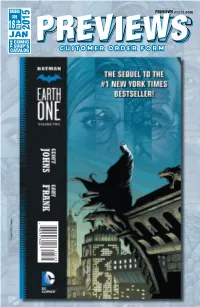

CUSTOMER ORDER FORM (Net)

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 JAN 2015 JAN COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jan15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:14:17 PM Available only from your local comic shop! STAR WARS: “THE FORCE POSTER” BLACK T-SHIRT Preorder now! BIG HERO 6: GUARDIANS OF THE DC HEROES: BATMAN “BAYMAX BEFORE GALAXY: “HANG ON, 75TH ANNIVERSARY & AFTER” LIGHT ROCKET & GROOT!” SYMBOL PX BLACK BLUE T-SHIRT T-SHIRT T-SHIRT Preorder now! Preorder now! Preorder now! 01 Jan15 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 12/4/2014 3:06:36 PM FRANKENSTEIN CHRONONAUTS #1 UNDERGROUND #1 IMAGE COMICS DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: EARTH ONE VOLUME 2 HC DC COMICS PASTAWAYS #1 DESCENDER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS JEM AND THE HOLOGRAMS #1 IDW PUBLISHING CONVERGENCE #0 ALL-NEW DC COMICS HAWKEYE #1 MARVEL COMICS Jan15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 12/4/2014 2:59:43 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Fox #1 l ARCHIE COMICS God Is Dead Volume 4 TP (MR) l AVATAR PRESS The Con Job #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Bill & Ted’s Most Triumphant Return #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 3 #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS/ARCHAIA PRESS Project Superpowers: Blackcross #1 l D.E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Angry Youth Comix HC (MR) l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 Hellbreak #1 (MR) l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: The Ninth Doctor #1 l TITAN COMICS Penguins of Madagascar Volume 1 TP l TITAN COMICS 1 Nemo: River of Ghosts HC (MR) l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Ninjak #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT BOOKS The Art of John Avon: Journeys To Somewhere Else HC l ART BOOKS Marvel Avengers: Ultimate Character Guide Updated & Expanded l COMICS DC Super Heroes: My First Book Of Girl Power Board Book l COMICS MAGAZINES Marvel Chess Collection Special #3: Star-Lord & Thanos l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #1 l COMICS Alter Ego #132 l COMICS Back Issue #80 l COMICS 2 The Walking Dead Magazine #12 (MR) l MOVIE/TV TRADING CARDS Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.