Moral Posturing: Body Language in Late Medieval Conduct Manuals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's Inside

TAKE ONE! June 2014 Paving the path to heritage WHAT’S INSIDE President’s message . 2 SHA memorials, membership form . 10-11 Picture this: Midsummer Night . 3 Quiz on Scandinavia . 12 Heritage House: New path, new ramp . 4-5 Scandinavian Society reports . 13-15 SHA holds annual banquet . 6-7 Tracing Scandinavian roots . 16 Sutton Hoo: England’s Scandinavian connection . 8-9 Page 2 • June 2014 • SCANDINAVIAN HERITAGE NEWS President’s MESSAGE Scandinavian Heritage News Vol. 27, Issue 67 • June 2014 Join us for Midsummer Night Published quarterly by The Scandinavian Heritage Assn . by Gail Peterson, president man. Thanks to 1020 South Broadway Scandinavian Heritage Association them, also. So far 701/852-9161 • P.O. Box 862 we have had sev - Minot, ND 58702 big thank you to Liz Gjellstad and eral tours for e-mail: [email protected] ADoris Slaaten for co-chairing the school students. Website: scandinavianheritage.org annual banquet again. Others on the Newsletter Committee committee were Lois Matson, Ade - Midsummer Gail Peterson laide Johnson, Marion Anderson and Night just ahead Lois Matson, Chair Eva Goodman. (See pages 6 and 7.) Our next big event will be the Mid - Al Larson, Carroll Erickson The entertainment for the evening summer Night celebration the evening Jo Ann Winistorfer, Editor consisted of cello performances by Dr. of Friday, June 20, 2014. It is open to 701/487-3312 Erik Anderson (MSU Professor of the public. All of the Nordic country [email protected] Music) and Abbie Naze (student at flags will be flying all over the park. Al Larson, Publisher – 701/852-5552 MSU). -

Seniors Housing Effort Revived THERE's RENEWED Optimism a Long-Sought Plan for a Crnment in 1991

Report card time He was a fighter Bring it onl We grade Terrace's city council on The city mourns the loss of one of how it rode out the ups and The Terrace Soirit Riders play hard its Iongtime activists for social downs of 2000\NEWS A5 and tough en route to the All- I change\COMMUNITYB1 Native\SPORTS B5 1 VOL. 13 NO. 41 WEDNESDAY m January 17, 2001 L- ,,,,v,,..~.,'~j~ t.~ilf~. K.t.m~ $1.00 PLUS 7¢ GST ($1.10 plus 8t GST outside of the Terracearea) TAN DARD ,| u Seniors housing effort revived THERE'S RENEWED optimism a long-sought plan for a crnment in 1991. construction. different kind of seniors housing here will actually hap- pen. Back then Dave Parker, the Social Credit MLA for The project collapsed at that point but did begin a re- Officials of the Terrace and Area Health Council Skeena, was able to have the land beside Terraceview Lodge tui'ned over by the provincial government to the vival when the health council got involved. have been meeting with provincial housing officials .to It already operates Terraceview Lodge so having it build 25 units of rental housing on land immediately ad- Terrace Health Care Society, the predecessor of the health council. also be responsible for supportive housing made sense, jacent to Terraceview Lodge. said Kelly. This type of accommodation is called supportive Several attempts to attract government support through the Dr. R.E.M. Lee Hospital Foundation failed. This time, all of the units will be rental ones, he housing in that while people can. -

EUI Working Papers

ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2010/75 ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUDO Citizenship Observatory DUAL CITIZENSHIP FOR TRANSBORDER MINORITIES? HOW TO RESPOND TO THE HUNGARIAN-SLOVAK TIT-FOR-TAT Edited by Rainer Bauböck EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE ROBERT SCHUMAN CENTRE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES EUROPEAN UNION DEMOCRACY OBSERVATORY ON CITIZENSHIP Dual citizenship for transborder minorities? How to respond to the Hungarian-Slovak tit-for-tat EDITED BY RAINER BAUBÖCK EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2010/75 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © 2010 Edited by Rainer Bauböck Printed in Italy, October 2010 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies (RSCAS), created in 1992 and directed by Stefano Bartolini since September 2006, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research and to promote work on the major issues facing the process of integration and European society. The Centre is home to a large post-doctoral programme and hosts major research programmes and projects, and a range of working groups and ad hoc initiatives. The research agenda is organised around a set of core themes and is continuously evolving, reflecting the changing agenda of European integration and the expanding membership of the European Union. -

The King's Nation: a Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand

THE KING’S NATION: A STUDY OF THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF NATION AND NATIONALISM IN THAILAND Andreas Sturm Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London (London School of Economics and Political Science) 2006 UMI Number: U215429 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U215429 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis, submitted in partial fulfillment o f the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and entitled ‘The King’s Nation: A Study of the Emergence and Development of Nation and Nationalism in Thailand’, represents my own work and has not been previously submitted to this or any other institution for any degree, diploma or other qualification. Andreas Sturm 2 VV Abstract This thesis presents an overview over the history of the concepts ofnation and nationalism in Thailand. Based on the ethno-symbolist approach to the study of nationalism, this thesis proposes to see the Thai nation as a result of a long process, reflecting the three-phases-model (ethnie , pre-modem and modem nation) for the potential development of a nation as outlined by Anthony Smith. -

A Companion to the French Revolution Peter Mcphee

WILEY- BLACKwELL COMPANIONS WILEY-BLACKwELL COMPANIONS TO EUROPEAN HISTORY TO EUROPEAN HISTORY EDIT Peter McPhee Wiley-blackwell companions to history McPhee A Companion to the French Revolution Peter McPhee Also available: e Peter McPhee is Professorial Fellow at the D BY University of Melbourne. His publications include The French Revolution is one of the great turning- Living the French Revolution 1789–1799 (2006) and points in modern history. Never before had the Robespierre: A Revolutionary Life (2012). A Fellow people of a large and populous country sought to of both the Australian Academy of the Humanities remake their society on the basis of the principles and the Academy of Social Sciences, he was made of popular sovereignty and civic equality. The a Member of the Order of Australia in 2012 for drama, success, and tragedy of their endeavor, and service to education and the discipline of history. of the attempts to arrest or reverse it, have attracted scholarly debate for more than two centuries. the french revolution Contributors to this volume Why did the Revolution erupt in 1789? Why did Serge Aberdam, David Andress, Howard G. Brown, it prove so difficult to stabilize the new regime? Peter Campbell, Stephen Clay, Ian Coller, What factors caused the Revolution to take Suzanne Desan, Pascal Dupuy, its particular course? And what were the Michael P. Fitzsimmons, Alan Forrest, to A Companion consequences, domestic and international, of Jean-Pierre Jessenne, Peter M. Jones, a decade of revolutionary change? Featuring Thomas E. Kaiser, Marisa Linton, James Livesey, contributions from an international cast of Peter McPhee, Jean-Clément Martin, Laura Mason, acclaimed historians, A Companion to the French Sarah Maza, Noelle Plack, Mike Rapport, Revolution addresses these and other critical Frédéric Régent, Barry M. -

Introductory Comment

Introductory Comment ROBERT A. SCHNEIDER I should begin by noting that, while I once worked on the eighteenth century, I am now, and have been for longer than I care to admit, stuck in the early seventeenth. So I have been out of the loop about many of the new developments in eighteenth-century studies. And these papers by Ellen Ledoux and Christy Pichichero remind me what I’ve been missing. Indeed, as both a rather naïve reader and as a historian—or do I repeat my- self?—one of the pleasures in reading them is simply learning things about which I had absolutely no idea. There were, as Ellen tells us, “hundreds” of figures of woman warri- ors “in popular ballads of the eighteenth and nineteenth century;” and, remarkably, ac- cording to a contemporary memoir, “many crossed-dressed women were found among the slain on in the field of Waterloo.” Who knew? I certainly didn’t. Christy’s revelations are perhaps less dramatic, but no less interesting. Who would have guessed that such ex- quisite solicitude for the well-being of soldiers, such authentic manifestations of sensibil- ity, such well-tuned humanitarian sentiments were evident, not only in the pampered sa- lons, but in the barracks of the eighteenth-century behemoth, the fiscal military state? (I almost expected Christy to tell us that—like my daughters in their grade school and soc- cer games in the era of “every child is excellent, every child wins”—every soldier got a gold star or a medal just for managing to show up for battle.) But beyond these revelations, these papers have, of course arguments. -

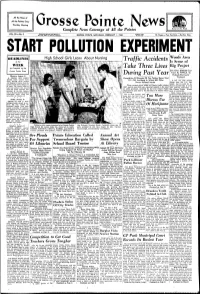

Traffic Accidents Rr°Od~Area of the ", ~ ."

All the News of .AII the Pointes Every Thursday Morning rosse Pointe 1 ewS Complete News Coverage of All the Pointes Home of the New! VOL 29-No. 5 Entered al Second CiaII Matter at t5 .00 Per Year thI Post OfficI at Detroit, M1eh1ellJl GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN, FEBRUARY I, 1968 IDe Per Copy 36 Pages-Two Sections-Section One IIEADLINES High School Girls Learn A~~~~f'::"""""-' Traffic Accidents rr°od~Area of the ", ~ .". ': .k- 'w '< ~.""1" ,,/$'/ '.., ' T k h s Scene of '''EEl{ . ,,';~':;'\\,~,' ..:t;. ~( :'t.:':" i;4,' ~:':>,:iII a e Tree L;ves Big ProJ.eet As Compiled by the , ~J.~~ ~'":::~>~ .../N~ ~~~"X~~,1r%:a.~~ " Grosse Pointe News ~...l!During Past Year D~~c~iVB~VSt~~~~~n. ,j I Evaluate Stormwater '11l.ursnay, January 25 A STRONG NEW EARTH. .~ I Compilation Of Re-c-o-rd-s-O-f -F-iv-e-Pointes Shows Total Treatment QUAKE shook western Sicily Of 1,352 Accidents In Which 500 Other A bill for $30 hillion today, burying rescue workers still digging for bodies from the Person Suffered Injuries hangs over the U,S. tax. island's worst quake disaster in I Three persons -\~eie--killed in-POinte traffic during payer, but it could be re- 60 years. The tremor killed at I 1967, and an. even 500 were reported injured in the total duced considerably if work least four persons and inj ul'ed of 1,352 aCCIdents recorded by the five Pointe Police just getting underway in about 50, police reported. The I " pepart~ents and sent to the Secretary of State's Office the Grosse Pointe Woods epicenter of Ihe new tremors '.i .'t..:.1,:.',',',1 In Lansmg. -

Thewestfield Leader During 1966 the Leading and Most Widely Circulated Weekly Newspaper in Union County

DRIVE TO EXIST THEWESTFIELD LEADER DURING 1966 THE LEADING AND MOST WIDELY CIRCULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPER IN UNION COUNTY Published Every Thursday 32 Pages—10 Cent* WESTFIELD^ NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, MARCH 10, 1966 School Pay Scales, Council OKs Budget; Leaves Approved Fife Again Dissents Girls! Sign Up Increases P Keglstratloit for girls soflbalt For In New Budget Open House Tax Rate Seen fans been extended until Satur- The Hoard of Kducalion Tuesday Salary Ordinances day. At the l'lay Fair, Sport night approved two teacher resigna- WcsUield families are Invited Center and YWl'A cards are tions, the appointment of six to the to an open house at the West- Up 26 Points available for girls aged 9-H, faculty, a schedule of financial pro- Provide Increases field Rescue Squad headquarters with 14 year olds eligible for Uie visions for teacher, office personnel, an Spring St. Sunday from 2 to Westfield's town budget first lime this year. All cards custodians and maintenance staff, 4 p.m. Guided tours of the fa- for 1966 calling for an out- must be In the hands of Uie salaries for staff personnel and a For Employees cilities will be offered, as well lay of $2,364,307 for muni- League )>y Saturday. salary guide for school nurses. displays und demonstrations of cipal purposes, an increase In addition the board rcappointed Town Council introduced two ordi- ItesuscI -Annie, the squad's of $40,000 over last year, Bert L. Itucbcr as custodian of the nances Tuesday night providing pay breathing dummy, and other and a total projected tax equipment. -

Studio Dragon Corporation (253450 KQ ) Temporary Lull

Studio Dragon Corporation (253450 KQ ) Temporary lull Media 2Q18 review: Temporary lull due to absence of tentpoles For 2Q18, Studio Dragon delivered consolidated revenue of W74.3bn (+19.6% YoY ) and operating profit of W7.3bn (-17.6% YoY). Revenue was 8% above the consensus Company Report (W68.5bn), but operating profit missed the consensus (W9.3bn) by 21%. Licensing sales August 9, 2018 were tepid, as 2Q18 was the only quarter of the year with no tentpole titles (i.e., those with production cost of W1bn per episode). Meanwhile, pro duction costs for regular titles increased, which was good for revenue, but bad for margins. That said, we view the 2Q18 profit figure as the minimum level of profits that can be expected, regardless of the commercial success of the company’s titles. (Maintain) Buy Programming revenue was strong, growing 41.1% YoY to W34.1bn, thanks to budget increases. All of the company’s six titles in 2Q18 were aired on captive channels. Target Price (12M, W) Following the success of Live and My Mister in March, dramas like What’s Wrong with 150,000 Secretary Kim (June) also did well, both critically and commercially (average ratings: +1.5%p). Licensing sales grew 9.5% YoY to W28.8bn. Despite the absence of tentpoles, Share Price (08/08/18, W) 96,000 overseas sales continued. The company also recognized some VoD sales of regular titles, sales of older titles, and part of the licensing sales for Live from Netflix (sold in 1Q18). Other revenue slipped 1.9% YoY to W11.4bn. -

Untitled Version in Typescript Indicates That It Was Written for the Guild Year Book (3); I Found No Record of Its Being Published

THE NEW MIDDLE AGES BONNIE WHEELER, Series Editor The New Middle Ages is a series dedicated to transdisciplinary studies of medieval cultures, with particular emphasis on recuperating women’s history and on feminist and gender analyses. This peer-reviewed series includes both scholarly monographs and essay collections. PUBLISHED BY PALGRAVE: Women in the Medieval Islamic World: Power, Chaucer’s Pardoner and Gender Theory: Bodies Patronage, and Piety of Discourse edited by Gavin R. G. Hambly by Robert S. Sturges The Ethics of Nature in the Middle Ages: On Crossing the Bridge: Comparative Essays on Boccaccio’s Poetaphysics Medieval European and Heian Japanese Women by Gregory B. Stone Writers edited by Barbara Stevenson and Presence and Presentation: Women in the Cynthia Ho Chinese Literati Tradition by Sherry J. Mou Engaging Words: The Culture of Reading in the Later Middle Ages The Lost Love Letters of Heloise and Abelard: by Laurel Amtower Perceptions of Dialogue in Twelfth-Century France Robes and Honor: The Medieval World of by Constant J. Mews Investiture edited by Stewart Gordon Understanding Scholastic Thought with Foucault Representing Rape in Medieval and Early by Philipp W. Rosemann Modern Literature edited by Elizabeth Robertson and For Her Good Estate: The Life of Elizabeth de Christine M. Rose Burgh by Frances A. Underhill Same Sex Love and Desire among Women in the Middle Ages Constructions of Widowhood and Virginity in edited by Francesca Canadé Sautman and the Middle Ages Pamela Sheingorn edited by Cindy L. Carlson and Angela Jane Weisl Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages: Ocular Desires Motherhood and Mothering in Anglo-Saxon by Suzannah Biernoff England by Mary Dockray-Miller Listen, Daughter: The Speculum Virginum and the Formation of Religious Women in the Listening to Heloise: The Voice of a Twelfth- Middle Ages Century Woman edited by Constant J. -

E-Catalogue 16 Recent Acquisitions

♦ MUSINSKY RARE BOOKS ♦ E-Catalogue 16 Recent acquisitions No. 21 www.musinskyrarebooks.com + 1 212 579-2099 [email protected] Powerful women having fun 1) ABBEY OF REMIREMONT – Kyriolés ou Cantiques Qui sont chantez à l'Eglise de Mesdames de Remiremont, par les jeunes filles de différentes Parroisses des Villages voisins de cette Ville, qui sont obligez d'y venir en procession le lendemain de la Pentecôte. Remiremont: chez Cl[aude] Nic[olas] Emm[anuel] Laurent, 1773. 8vo (185 x 115 mm). [3], 4-14, [2] pp. Four large woodcuts, printed one to a page on the first and last leaves, within various woodcut and typographic ornamental borders. Woodcut headpiece, type ornaments. Dark green 19th-century quarter morocco, pale green paper flyleaves. $3400 ONLY EDITION, an unusual piece of popular printing, memorializing an ancient religious ritual held yearly on Pentecost Monday at the female Abbey of Remiremont in the Vosges. This ancient establishment had been founded in the 7th century as a double monastery of monks and nuns, under the austere rule of Saint Columbanus, by Saints Amé (or Aimé) and Romaric, who served successively as its first abbots. The mens’ monastery disappeared early on, and in the early 9th century the nuns embraced the more flexible Benedictine rule. The Abbey gradually became a secularized elite institution, reserved for women who could prove sixteen quarters of nobility on both paternal and maternal sides. These exigences were common to several other aristocratic chapters in Lorraine, but Remiremont was the richest of all the Lorraine abbeys, and its chanoinesses, known as les Dames de Remiremont, enjoyed all the privileges of a secular life, including marriage, and shared in the Abbey’s considerable income. -

Read Book What Is a Child?

WHAT IS A CHILD? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Beatrice Alemagna | 36 pages | 20 Sep 2016 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849764124 | English | London, United Kingdom What is a Child? PDF Book Audio help More spoken articles. In other states, it has to be proven that the drugs were used in the presence of the child. Minor Age of majority. The Issue What is Child Abuse? Retrieved 9 October Examples of medical neglect: Not taking child to hospital or appropriate medical professional for serious illness or injury Keeping a child from getting needed treatment Not providing preventative medical and dental care Failing to follow medical recommendations for a child Educational Neglect Parents and schools share responsibility for making sure children have access to opportunities for academic success. We have a free legal aid directory here. They must also provide basic preventive care to make sure their child stays safe and healthy. Ken discusses how the relationship between parent and child must evolve as the child ages, and how any theory of parental authority must take that into account. Is the word kid slang? Social Forces, Vol. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Children Paternalism Family Ethics. Ken points out that there are two main ways to consider children--in terms of the differences between children and adults from a developmental perspective, and questions concerning the moral status of children compared to adults. Listen to this article. In some cases, both the offender and the victim may be removed from the home. Join John and Ken as they reflect on the nature of childhood. This is also known as Munchhausen by Proxy.