Forging Connections: Anthologies, Arts Collectives, and the Politics of Inclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer 2011 Issue 36

Express Summer 2011 Issue 36 Portrait of a Survivor by Thomas Ország-Land John Sinclair by Dave Russell Four Poems from Debjani Chatterjee MBE Per Ardua Ad Astra by Angela Morkos Featured Artist Lorraine Nicholson, Broadsheet and Reviews Our lastest launch: www.survivorspoetry.org ©Lorraine Nicolson promoting poetry, prose, plays, art and music by survivors of mental distress www.survivorspoetry.org Announcing our latest launch Survivors’ Poetry website is viewable now! Our new Survivors’ Poetry {SP} webite boasts many new features for survivor poets to enjoy such as; the new videos featuring regular performers at our London events, mentees, old and new talent; Poem of the Month, have your say feedback comments for every feature; an incorporated bookshop: www.survivorspoetry.org/ bookshop; easy sign up for Poetry Express and much more! We want you to tell us what you think? We hope that you will enjoy our new vibrant place for survivor poets and that you enjoy what you experience. www.survivorspoetry.org has been developed with the kind support of all the staff, board of trustess and volunteers. We are particularly grateful to Judith Graham, SP trustee for managing the project, Dave Russell for his development input and Jonathan C. Jones of www.luminial.net whom built the website using Wordpress, and has worked tirelessly to deliver a unique bespoke project, thank you. Poetry Express Survivors’ Poetry is a unique national charity which promotes the writing of survivors of mental 2 – Dave Russell distress. Please visit www.survivorspoetry. com for more information or write to us. A Survivor may be a person with a current or 3 – Simon Jenner past experience of psychiatric hospitals, ECT, tranquillisers or other medication, a user of counselling services, a survivor of sexual abuse, 4 – Roy Birch child abuse and any other person who has empathy with the experiences of survivors. -

Debjani Chatterjee

Monkey King's Party Debjani Chatterjee Illustrated by Simon Walmesley & James Walmesley This ebook belongs to: Published by Poggle Press, an imprint of Indigo Timmins Ltd • Pure Offices • Leamington Spa • Warwickshire CV34 6WE ISBN: 978-0-9573501-2-0 Text © Debjani Chatterjee 2013 Illustration © Simon Walmesley & James Walmesley 2013 All rights reserved. Debjani Chatterjee and Simon Walmesley & James Walmesley have asserted their moral right to be identified as the author and artists respectively of the work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is sold subject to the condition that it will not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without any similar condition, including this condition, being imposed upon the subsequent purchaser. www.springboardstories.co.uk Monkey King's Party Debjani Chatterjee An adaptation of a story from The Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en Illustrated by Simon Walmesley & James Walmesley A Poggle Press publication For Rishi – Munnu Dida Monkey King lived on the beautiful Fruit ‘n’ Flower Mountain. All the monkeys loved him because he was funny, friendly and brave. However, he was also very cheeky. Monkey King loved his mountain. He loved its flowers and he loved its fruits. But most of all, he loved to party. One day a traveller called Lao Tzu passed by. Monkey King saw that he was tired and hungry, so offered him some fruits. -

Tim Grayson on Wakefield Writers DVD Featured Artist Colin Hambrook of DAO SP Patron Debjani Chatterjee MBE Peter H

Poetry Express The Survivors’ Poetry Quarterly Newsletter Spring 2008 Issue 26 Tim Grayson on Wakefield Writers DVD Featured Artist Colin Hambrook of DAO SP Patron Debjani Chatterjee MBE Peter H. Donnelly on Curing Negative Hearing Voices Survivors’ Poetry still seeking funding, with only part time staff and volunteers; shoestring funds for the office, Outreach, and workshops but Events still going strong see Events page... 1promoting poetry, prose, plays, art and music by survivors of mental distress S u r v i v o r s ’ P o e t r y Publications http://www.survivorspoetry.com/SP_Shop/ Poem of the Month October 2007 Hillside, Llangattock We think with our shoulders. On the lime-quarried hillside down a stony lane lined with ash and hazel a poor disused chapel where fierce hymns give men courage. Hardship on this hillside, riven by lime and bracken, thistle and scree. A cold, slow rain on a cottage in the dell mortared with the blood of quarrymen hill-farmers. Sheep grieve above the oak wood where a mistle-thrush storms hell. A feral cat hunts the black redstart; so rare, so shy. Cover design and edited by Alan Morrison November beeches aflame, as many fallen leaves as slain quarry men. Resistance of pain in the chest and spat gob. From a dry-stone wall, Jenny Wren’s song holier than remembrance. Dangerous to take the sheep track at dusk. The blessedness of February wind through an old goat-willow. Here men pray with their stomachs: the gnarled upland cabbage in a broth with barley. The language of hunger: an alcoholic’s lack. -

Gitanjali and Beyond Rabindranath Tagore and the Environment Vol 2

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14297/gnb.2 GITANJALI AND BEYOND http://gitanjaliand beyond.napier.ac.uk ISSN 2399-8733 Gitanjali and Beyond Rabindranath Tagore and the Environment Vol 2 1 Editor-in Chief: Bashabi Fraser Deputy Editor: Christine Kupfer Assistant Editor: Kathryn Simpson Published by The Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies (ScoTs) Edinburgh Napier University © The contributors 2018 Designed & Typeset: Aboli Kulkarni (Publishing, Edinburgh Napier University) 2 GITANJALI AND BEYOND Editorial Board Dr Liz Adamson Artist & Curator, Edinburgh College of Art. Prof Fakrul Alam Professor of English, University of Dhaka Dr Imre Bangha Associate Professor of Hindi, University of Oxford. Prof Elleke Boehmer Writer and critic, Professor of World Literature in English, Director of Oxford Humanities Centre, English Faculty, University of Oxford. Prof Ian Brown Playwright, Poet, Emeritus Professor, Kingston University, London. Dr Amal Chatterjee Writer. Dr Debjani Chatterjee MBE, Poet, Writer, Creative Arts Therapist, Associate, Royal Literary Fellow. Dr Rosinka Chaudhuri Professor of Cultural Studies, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata. Dr Sangeeta Datta Filmmaker SD Films/ independent Tagore Scholar. Prof Sanjukta Dasgupta Professor of English, Universityof Calcutta. Prof Uma Das Gupta Historian and Tagore biographer. Dr Stefan Ecks Social Anthropology,University of Edinburgh. Prof Mary Ellis Gibson Professor of English, Colby College, Waterville, ME, USA. Prof Tapati Gupta Professor emer., Department of English, Calcutta University, Tagore scholar and independent researcher of intercultural theatre. 3 Prof Kaiser Md. Hamidul Haq Poet, Professor of English, University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh. Dr Michael Heneise Anthropologist, Edinburgh University. Dr Dr Martin Kaempchen Writer and Translator of Tagore. Usha Kishore Poet and Translator. -

Rabindranath Tagore 1

2016 Gitanjali & Beyond Hau: Issue 1, Vol. 1 (2016): Tagore & Spirituality Journal http://dx.doi.org/10.14297/gnb.1.1 http://gitanjaliandbeyond.napier.ac.uk of Tagore and Beyond 1 (1): 10 - 69 Editor-in Chief: Bashabi Fraser Deputy Editor: Christine Kupfer Published by The Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies (ScoTs) Edinburgh Napier University © The contributors 2016 Editorial Board Dr Liz Adamson Dr Sangeeta Datta Artist & Curator, Edinburgh Filmmaker SD Films; College of Art. independent Tagore Scholar. Prof Fakrul Alam Prof Sanjukta Dasgupta Professor of English, Professor of English, University University of Dhaka of Calcutta. Dr Imre Bangha Prof Uma Das Gupta Associate Professor of Hindi, Historian and Tagore biographer. University of Oxford. Dr Stefan Ecks Ursula Bickelmann School of Social and Political Independent Art Historian Science, University of Edinburgh Prof Elleke Boehmer Prof Mary Ellis Gibson Writer and critic; Professor of English, Colby Professor of World Literature in College, Waterville, ME, USA. English, Director of Oxford Humanities Centre Prof Tapati Gupta English Faculty, University of Professor emer., Department of Oxford. English, Calcutta University, Tagore scholar and independent Prof Ian Brown researcher of intercultural Playwright, Poet, Emeritus theatre. Professor, Kingston University, London. Prof Kaiser Md. Hamidul Haq Poet, Professor of English Colin Cavers University of Liberal Arts, Photography, Edinburgh College Bangladesh. of Art. Dr Michael Heneise Dr Amal Chatterjee Director, The Kohima Institute Writer. Nagaland, India Dr Debjani Chatterjee Dr Dr Martin Kaempchen MBE, Poet, Writer, Creative Arts Writer and Translator of Tagore. Therapist, Associate, Royal Literary Fellow. Mary-Ann Kennedy Photography, Edinburgh Napier Dr Rosinka Chaudhuri University. Professor of Cultural Studies, Centre for Studies in Social Usha Kishore Sciences, Kolkata. -

Bibliotheca Phoenix

- 59 - BIBLIOTHECA PHOENIX Elisabetta Marino Voicing the Silence: Exploring the Work of the “Bengali Women’s Support Group” in Sheffield BIBLIOTHECA PHOENIX by CARLA ROSSI ACADEMY PRESS www.cra.phoenixfound.it CRA - INITS MMVIII © Copyright by Carla Rossi Academy Press Carla Rossi Academy – International Institute of Italian Studies Monsummano Terme – Pistoia Tuscany - Italy www.cra.phoenixfound.it All Rights Reserved Printed in Italy MMVIII ISBN 978-88-6065-090-0 C O L O P H O N PRIMA EDIZIONE LIMITATA A TRENTATRÉ ESEMPLARI CON TIMBRO E VIDIMAZIONE UFFICIALE CRA-INITS Volume n° VI / XXXIII composto con il carattere Times New Roman e stampato su carta bianco latte in fibra di Eucalyptus Globulus con inchiostro India 8 Elisabetta Marino Voicing the Silence: Exploring the Work of the “Bengali Women’s Support Group” in Sheffield Even if the 1991 census report identified the Bangladeshis as “the youngest and fastest growing of all the ethnic populations” settled in Britain (Eade 1996, 150), British Bangladeshi communities across the UK have long suffered from isolation and neglect, being almost invisible to the eyes of the mainstream society. Apart from a single, controversial case — that of writer Monica Ali and her 2003 debut novel entitled Brick Lane — their voices seem to be still unheard, shrouded in an impenetrable silence which has forcibly turned them into “highly segregated” (Ali, 7) and tightly knit enclaves (where women are still relegated to a secondary role), or into anachronistic and displaced Banglatowns, “encapsulated” — as -

Notes on Contributors Susan Bassnett Is Pro-Vice-Chancellor at the University of Warwick, UK, and Professor in the Centre for Tr

Notes on Contributors Susan Bassnett is Pro-Vice-Chancellor at the University of Warwick, UK, and Professor in the Centre for Translation and Comparative Cultural Studies which she founded in the 1980s. She was educated in several European countries, which gave her a grounding in diverse languages and cultures. She has lectured in universities around the world, and began her academic career in Italy, moving via the United States to the University of Warwick, where she set up a post-graduate centre in intercultural studies that now has a thriving international population of some eighty students. She is author of over twenty books, and her Translation Studies, (3rd ed., London: Routledge, 2002) which first appeared in 1980, has remained consistently in print and has become an important textbook around the world in the expanding field of Translation Studies. Her Comparative Literature: A Critical Introduction (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993) has also become an internationally renowned work and has been translated into several languages. Recent books include Constructing Cultures (Multilingual Matters, 1998) written with André Lefevere, and Post-Colonial Translation (Routledge, 1999) co-edited with Harish Trivedi. She edited Studying British Culture: An Introduction (Routledge, 1997), and, with Ulrich Broich, Britain at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century (Amsterdam and Atlanta, GA: Rodopi, 2001), while her new book Studying British Cultures will be published by Routledge in August 2003. Besides her academic research, Susan Bassnett writes poetry. Her latest collection of poems and creative translations (from Alejandra Pizarnik) is Exchanging Lives (Leeds: Peepal Tree, 2002). As well as her book of translations with Piotr Kuhiwczak, Ariadne’s Thread: Polish Women Poets (London and Boston: Forest Books/UNESCO, 1988), which includes “Children of This Age,” she has published many other translations, including Margo Glantz’s The Family Tree (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1991). -

Locating the Diasporic Consciousness in the Select Poems of Sujata Bhatt and Debjani Chatterjee

Goutam Karmakar 2020, Vol. 17 (2), 149-164(284) Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, revije.ff.uni-lj.si/elope West Bengal, India https://doi.org/10.4312/elope.17.2.149-164 UDC: UDK 821.111(73).09-1Bhatt S. UDK 821.111.09-1Chatterjee D. Formulating the ‘Alternate Archives’ of Produced Locality: Locating the Diasporic Consciousness in the Select Poems of Sujata Bhatt and Debjani Chatterjee ABSTRACT The present paper aims to outline the diasporic consciousness in two Indian diasporic women poets namely, Sujata Bhatt and Debjani Chatterjee. The poets’ diasporic consciousness is strewn with the nostalgia for lost homes, pangs of homelessness, fractured identity, the disintegrated historiography of displaced individuals, persistent ‘post-memory’ and continuous struggle to assimilate into the environment of ‘hostland’. This assimilation is achieved by transcending the geographical and psychological borders of ‘homeland’ as seen in the selected poems of Bhatt and Chatterjee. The paper also attempts to show how the poets formulate ‘alternate archives’ by delineating their discourses of displacement (Hirsch and Smith 2002) of produced locality. Keywords: diasporic consciousness, homeland, hostland, identity, memory, nostalgia Oblikovanje 'alternativnih arhivov' ustvarjene lokalnosti: Prisotnost diasporske zavesti v izbranih pesmih Sujate Bhatt in Debjani Chatterjee POVZETEK Članek zariše diasporsko zavest v pesmih indijskih diasporskih pesnic Sujati Bhatt in Debjani Chatterjee. Njuno diasporsko zavest zaznamuje nostalgija za izgubljenimi domovi, bolečina brezdomskosti, zlomljena identiteta, razpadla historiografija dislociranih posameznikov, vztrajni 'po-spomin' in nenehni poskusi vključevanja v 'gostiteljska' okolja. Izbrane pesmi Sujate Bhatt and Debjani Chatterjee kažejo, da je takšno vključevanje mogoče s preseganjem geografskih in psiholoških meja 'domovine'. V prispevku pokažem tudi, kako pesnici oblikujeta 'alternativne arhive' z zarisom diskurzov dislociranosti (Hirsch in Smith 2002) ustvarjene lokalnosti. -

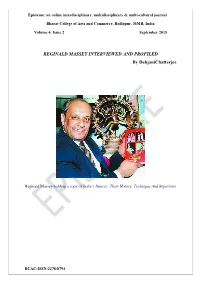

REGINALD MASSEY INTERVIEWED and PROFILED by Debjanichatterjee

Episteme: an online interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary & multi-cultural journal Bharat College of Arts and Commerce, Badlapur, MMR, India Volume 4, Issue 2 September 2015 REGINALD MASSEY INTERVIEWED AND PROFILED By DebjaniChatterjee Reginald Massey holding a copy of India’s Dances: Their History, Technique And Repertoire BCAC-ISSN-2278-8794 Episteme: an online interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary & multi-cultural journal Bharat College of Arts and Commerce, Badlapur, MMR, India Volume 4, Issue 2 September 2015 An archive photo of Reginald Massey presents his book The Music of India to Pandit Ravi Shankar, who had written its foreword About REGINALD MASSEY Reginald Massey is a name that is respected in literary circles, but deserves to be much better known to the general reader, especially in South Asia. An eclectic writer, he is an authority on classical Indian music, dance and culture; a historian; a fiction writer; a critic; a columnist; and a poet. He wrote and narrated the BBC's well known documentary on Kerala’s ancient dance drama - Kathakali. He also wrote and produced a travel-documentary, Bangladesh I Love You, starring the boxing celebrity Muhammad Ali. He has written for leading British papers, e.g. The Times, The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph and The Independent. He is a critic for The Dancing Times of London and regularly writes on books and authors for Confluence e-zine and Pakistan’s leading newspaper Dawn. He is Consultant Editor of the Welsh magazine of history and art, PenCambria. Massey has also contributed to several encyclopaedia entries on Indian music and dance. BCAC-ISSN-2278-8794 Episteme: an online interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary & multi-cultural journal Bharat College of Arts and Commerce, Badlapur, MMR, India Volume 4, Issue 2 September 2015 He was born in Lahore in British India on 23rd November 1932.When his family migrated to India at the time of Partition, 15 year-old Massey witnessed terrible massacres along the way. -

Across the Margins: Cultural Identity and Change in the Atlantic Archipelago Norquay, Glenda (Ed.); Smyth, Gerry (Ed.)

www.ssoar.info Across the margins: cultural identity and change in the Atlantic archipelago Norquay, Glenda (Ed.); Smyth, Gerry (Ed.) Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerk / collection Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Norquay, G.a., & Smyth, G. (Eds.). (2002). Across the margins: cultural identity and change in the Atlantic archipelago. Manchester: Manchester Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-271145 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de 1 Across the margins Norquay_00_Prelims 1 22/3/02, 9:26 am Norquay_00_Prelims 2 22/3/02, 9:26 am Across the margins Cultural identity and change in the Atlantic archipelago EDITED BY GLENDA NORQUAY AND GERRY SMYTH Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Norquay_00_Prelims 3 22/3/02, 9:27 am Copyright © Manchester University Press 2002 While copyright in the volume is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective -

DP13908 46 This Document Is Printed on 75% Recycled Paper 47 Off the Shelf Festival of Words

Off the Shelf Festival of Words Sheffield 12 October - 2 November 2013 Platinum Sponsor Introduction Welcome to Off the Shelf Festival of Words, now in its 22nd year and one of the highlights of the city’s events calendar. If you love words and are looking for a diverse and exciting programme of events, including some of the best known names in Gold Sponsor literature and media, look no further. We are delighted that we have our first female guest curator this year - writer Jackie Kay. Jackie’s poem, commissioned last year for the Kick it Out anti-racism campaign, can now be seen permanently at Sheffield United’s Bramall Lane ground. We are very grateful to Platinum Sponsor Civica and Arts Council England and to all our supporters and sponsors for their fantastic support. We would also like to thank our Silver Sponsor audiences - over 25,000 people attended the festival last year and we hope to welcome even more of you this year. Enjoy…. Cllr Isobel Bowler Paul Billington Cabinet Member for Culture, Sport and Leisure Director Culture and Environment Off the Shelf is organised by Sheffield City Library Events: Events in Libraries have been Council’s Major Events Service. organised by Sheffield Libraries Archives and For further information about Off the Shelf Information - Alex Holyoake, Joanne Parkes, please contact: Dan Marshall, Wendy Hudson, Sandra Goacher Off the Shelf Festival of Words, Sheffield City Brochure Cover Image: © Matt Sewell Council, Room 311, Town Hall, Pinstone Street, Brochure Design: Sheffield City Council, Sheffield S1 2HH Communications Services Telephone: 0114 273 4716/273 4400 Festival Bookseller: Rhyme and Reason Support and resources for people who write e-mail: [email protected] Festival Website: Marketing Sheffield Website: www.offtheshelf.org.uk We would like to thank The Arena Ticket Shop Off the Shelf Festival of Words for providing a one stop box office outlet and for their generous support of the festival. -

Gitanjali and Beyond Issue 3 Typeset

Gitanjali & Beyond Issue 3 DOI gitanjaliandbeyond.co.uk ISSN: 2399-8733: , doi ( 201 .org/10.14297/gnb.3 9 ): Across Cultures Gitanjali and Beyond Across Cultures - A Special Issue Issue 3 Gitanjali and Beyond Across Cultures A Special Issue: Issue 3 Interviews, Reviews and Creativity Summer, 2019 A Journal of the Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies (ScoTs) Edinburgh Napier University Editor-in-Chief: Bashabi Fraser Assistant Editor: Kathryn Simpson 2 Editorial Team Editor-in-Chief Prof Bashabi Fraser Emeritus Professor; Director, Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies (ScoTs), School of Arts and Creative Industries, Edinburgh Napier University, United Kingdom. Associate Editors Dr Kathryn Simpson Edinburgh Napier University, United Kingdom. Dr Saptarshi Mallick Department of English, Sanskrit University, Kolkata, India. Editorial Board Dr Christine Kupfer Tagore Scholar, United Kingdom. Prof Fakrul Alam Retired Professor of English, University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Prof Elleke Boehmer Professor of World Literature in English, University of Oxford., United Kingdom. Prof Imre Bangha Department of Oriental Studies, University of Oxford, United Kingdom. Professor Ian Brown Retired Professor of Drama and Dance, Kingston University, London, United Kingdom. Mr Colin Cavers Department of Photography, Edinburgh Napier University, United Kingdom. Mr Amal Chatterjee Writer, Tutor in Creative Writing, University of Oxford, based in the Netherlands. Dr Debjani Chatterjee MBE, Royal Literary Fund Fellow, De Montford University, United Kingdom. Prof Rosinka Chaudhuri Director, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata, India. Prof Uma Das Gupta Historian and Tagore Biographer, India. 3 Prof Sanjukta Dasgupta Dept of English Calcutta University India. Dr Gillian Dooley Honorary Senior Research Fellow, Flinders University Adelaide Australia. Dr Stefan Ecks School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom.