Hamilton's Rule Preprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building a Popular Science Library Collection for High School to Adult Learners: ISSUES and RECOMMENDED RESOURCES

Building a Popular Science Library Collection for High School to Adult Learners: ISSUES AND RECOMMENDED RESOURCES Gregg Sapp GREENWOOD PRESS BUILDING A POPULAR SCIENCE LIBRARY COLLECTION FOR HIGH SCHOOL TO ADULT LEARNERS Building a Popular Science Library Collection for High School to Adult Learners ISSUES AND RECOMMENDED RESOURCES Gregg Sapp GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sapp, Gregg. Building a popular science library collection for high school to adult learners : issues and recommended resources / Gregg Sapp. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–28936–0 1. Libraries—United States—Special collections—Science. I. Title. Z688.S3S27 1995 025.2'75—dc20 94–46939 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 1995 by Gregg Sapp All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 94–46939 ISBN: 0–313–28936–0 First published in 1995 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 To Kelsey and Keegan, with love, I hope that you never stop learning. Contents Preface ix Part I: Scientific Information, Popular Science, and Lifelong Learning 1 -

Interview with Martin Gardner Page 602

ISSN 0002-9920 of the American Mathematical Society june/july 2005 Volume 52, Number 6 Interview with Martin Gardner page 602 On the Notices Publication of Krieger's Translation of Weil' s 1940 Letter page 612 Taichung, Taiwan Meeting page 699 ., ' Martin Gardner (see page 611) AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY A Mathematical Gift, I, II, Ill The interplay between topology, functions, geometry, and algebra Shigeyuki Morita, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan, Koji Shiga, Yokohama, Japan, Toshikazu Sunada, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan and Kenji Ueno, Kyoto University, Japan This three-volume set succinctly addresses the interplay between topology, functions, geometry, and algebra. Bringing the beauty and fun of mathematics to the classroom, the authors offer serious mathematics in an engaging style. Included are exercises and many figures illustrating the main concepts. It is suitable for advanced high-school students, graduate students, and researchers. The three-volume set includes A Mathematical Gift, I, II, and III. For a complete description, go to www.ams.org/bookstore-getitem/item=mawrld-gset Mathematical World, Volume 19; 2005; 136 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3282-4; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/19 Mathematical World, Volume 20; 2005; 128 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3283-2; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/20 Mathematical World, Volume 23; 2005; approximately 128 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3284-0; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/23 Set: Mathematical World, Volumes 19, 20, and 23; 2005; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3859-8; List US$75;AII AMS members US$60; Order code MAWRLD-GSET Also available as individual volumes .. -

Developmental Biology: a Very Short Introduction PDF Book

DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY: A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lewis Wolpert | 152 pages | 02 Sep 2011 | Oxford University Press | 9780199601196 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Developmental Biology: A Very Short Introduction PDF Book Vertebrates 3. Fashion is a gigantic global industry, generating some three hundred billion dollars in revenue every year, and playing a significant role in the economic, political, cultural and social lives of a vast international audience. For questions on access or troubleshooting, please check our FAQs , and if you can't find the answer there, please contact us. Get A Copy. There have been an increasing amount of studies with iPS cells since there seems to be ethical issues with using ES cells, despite these being harvested when an embryo could still split and turn into twins telling scientists it should not be classified as human life. Sort order. This Very Short Introduction decodes the key themes, signs, and symbols found in Christian art: the Eucharist, the image of the Crucifixion, the Virgin Mary, the Saints, Old and New Testament narrative imagery, and iconography. Advanced Search. From a single cell--a fertilized egg--comes an elephant, a fly, or a human. Search Items. Members save with free shipping everyday! Details if other :. Evolutionary Genetics: Concepts, Analysis, and Practice. In this Very Short Introduction, renowned scientist Lewis Wolpert shows how the field of developmental biology seeks to answer these profound questions. See 1 question about Developmental Biology…. Request Examination Copy. For the last A distinguished developmental biologist himself, Wolpert offers a concise and highly readable account of what we now know about development, discussing the first vital steps of growth, the patterning created by Hox genes and the development of form, embryonic stem cells, the timing of gene expression and its management, chemical signaling, and growth. -

Varieties of Modules: Kinds, Levels, Origins, and Behaviors RASMUS G

116JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL R.G. WINTHER ZOOLOGY (MOL DEV EVOL) 291:116–129 (2001) Varieties of Modules: Kinds, Levels, Origins, and Behaviors RASMUS G. WINTHER* Department of History and Philosophy of Science, and Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47405 ABSTRACT This article began as a review of a conference, organized by Gerhard Schlosser, entitled “Modularity in Development and Evolution.” The conference was held at, and sponsored by, the Hanse Wissenschaftskolleg in Delmenhorst, Germany in May, 2000. The article subse- quently metamorphosed into a literature and concept review as well as an analysis of the differ- ences in current perspectives on modularity. Consequently, I refer to general aspects of the conference but do not review particular presentations. I divide modules into three kinds: struc- tural, developmental, and physiological. Every module fulfills none, one, or multiple functional roles. Two further orthogonal distinctions are important in this context: module-kinds versus mod- ule-variants-of-a-kind and reproducer versus nonreproducer modules. I review criteria for indi- viduation of modules and mechanisms for the phylogenetic origin of modularity. I discuss conceptual and methodological differences between developmental and evolutionary biologists, in particular the difference between integration and competition perspectives on individualization and modular behavior. The variety in views regarding modularity presents challenges that require resolution in order to attain a comprehensive, -

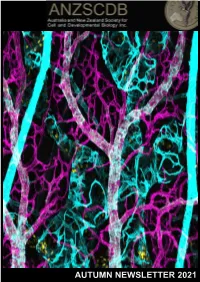

Autumn Newsletter 2021

AUTUMN NEWSLETTER 2021 Autumn NEWSLETTER – March 2021 Dear ANZSCDB members, ANZSCDB welcomes you to 2021, the year we emerge from the shadow of COVID-19 and work towards a return to the ‘normal’ routines of science, academia, research and industry. The local and global emergence from the pandemic is perhaps slower, more sporadic and less ‘normal’ than is ideal, and it still comes with significant hardship for many. However, hope abounds. We at ANZSCDB are committed to reconnecting with our members this year through a series of newsletters, satellite meetings and other forums, as detailed in this newsletter. While travel is still impeded, in-person conferences remain impractical and so we will be reaching out through locally held meetings which offer bi-national online access. We really hope that members will reach out and interact through these satellite meetings. Our interactions and shared science this year are critical to seed the planning of future meetings and conferences. Next year is the target for returning to full, in-person meetings, notably with ComBio planned for a return in 2022. The exceptional dedication and hard work of our Executive, Committees and State representatives will be on display through this year, ‘making it happen’ for all of us. Many are still in the midst of grant writing season and/or starting the year’s teaching. Both can be stressful for many reasons at this time, including our dwindling levels of government research funding and pressures on university budgets. I hope that this year also sees some improvement in this landscape. A reflection on the how the pandemic has unfolded and In this issue the world’s response over the past year, has profound missives for scientific research. -

Introduction Designing the French Flag

Rüdiger Wehner Introduction Designing the French flag (Ernst Mayr Lecture on 6th November 2001) Believe it or not: “It is not birth, marriage, or death, but gastrulation, which is truly the most important time in your life.” You may not easily agree with this statement made by Lewis Wolpert some 15 years ago, because you, like me and most others, may not have too vivid recollections of what happened between the 16th and 20th day of our early unborn lives. Nevertheless Wolpert’s remark is well-turned. It is during gastrulation, during this dramatic sequence of invaginations, involutions and ingressions of migrating layers of cells, that your major body plan has been shaped; and it was the young Wolpert who has unveiled much of the mystery of how these spectacular rearrangements of embryonic tissues are orchestrated. In fact, Lewis Wolpert started his career in developmental biology with one of his most stunning achievements. In the early 1960s, while doing his Ph.D. and post- doctoral work at King’s College, University of London, he unravelled the mechan- ics and dynamics of the act of gastrulation. By using time-laps film recordings and theoretical modelling – a combination of techniques quite new in those days – he was able to show that the primary force of all the microscopic events occurring during this early stage of morphogenesis is cell motility. He was a successful visionary in emphasizing that interactions of rather simple changes in cell shape and cell contact could give rise to amazingly complex forms of embryonic development. In present- day biology we are quite used to the astonishing contrast between the simplicity of primary events and the depth of the resulting behaviour, but when Wolpert wrote his early papers it took a certain chutzpah to make such claims. -

Positional Information and Patterning Revisited Lewis Wolpert

Positional information and patterning revisited Lewis Wolpert To cite this version: Lewis Wolpert. Positional information and patterning revisited. Journal of Theoretical Biology, Elsevier, 2010, 269 (1), pp.359. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.10.034. hal-00653684 HAL Id: hal-00653684 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00653684 Submitted on 20 Dec 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Author’s Accepted Manuscript Positional information and patterning revisited Lewis Wolpert PII: S0022-5193(10)00579-5 DOI: doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.10.034 Reference: YJTBI6218 To appear in: Journal of Theoretical Biology www.elsevier.com/locate/yjtbi Received date: 13 October 2010 Accepted date: 26 October 2010 Cite this article as: Lewis Wolpert, Positional information and patterning revisited, Journal of Theoretical Biology, doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.10.034 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. -

Hitting the Target

spring books complexity. With time, Benzer himself real- ized that Drosophila are not behavioural atoms but rather intricate individuals. He abandoned behavioural for developmental analysis. No doubt, Weiner was captivated by the eccentric style of Benzerism, and this encouraged him to recite scores of amusing anecdotes. Whether all appeal to the general public, or only to a small cult, is a different question. Another caveat is also appropriate: stu- dents who read the book should not expect mainstream science to follow Benzer’s model. Most laboratory work is much more boring than the hunt for bizarre mutants in the forefront of science. Most mentors are much less imaginative, daring and permis- sive than Benzer. And, unfortunately, the days are long gone when an enthusiastic investigator shared plans without fear, and mutants without a lawyer. This was before business killed fair play. Tracing the development of lines As for Benzer himself — at the age of 77 he has just discovered a new mutant, The artistic development of talented and less Development in Children: Comparative Methuselah, that refuses to age. talented children was compared over a ten-year Studies of Talent (Cambridge University Yadin Dudai is at the Weizmann Institute of period by the developmental psychologist Press, £40, $59.95). Milbrath describes Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel. Constance Milbrath. She assessed the ages of the development of artistic talent as development of different elements of drawing, being dependent on both figurative and including form, spatial relationships and cognitive abilities. Here, a talented composition. The study has been written up in 11-year-old has drawn the back views of Hitting a technical book, Patterns of Artistic two people and a dog. -

Thinking Like a Man? the Cultures of Science

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Published in Women: a cultural review, vol 14, issue 1, pp. 1 – 19. ISSN 0957-4042. © Taylor and Francis Ltd., 2003 Thinking Like a Man? The Cultures of Science. Lynne Segal ‘Reading too much to see, writing too much to think’, licensed intellectuals today are usually too cut off from wider audiences even to deserve the Wildean derision they once received. Yet the public domain has its well- known hazards. Academics rarely set its agenda, even when we do manage to address an audience beyond the barely-read journals stringent funding bodies force us into. Accordingly, I did not set the agenda when I agreed to present a session in Birkbeck's public lecture series: Close Encounters: Culture Meets Science. An odd situation, when I have tried to be the sternest critic of the dualism such ‘encounter’ excites - however intimate. The battle lines are familiar in Britian’s upmarket media: while well- known psychiatrist Raj Persuad can be heard arguing that science needs art, the equally recognizable biologist Lewis Wolpert insists that never the twain shall meet. Beyond binary conflicts, however, not only does culture include science but, more significantly, science includes culture. To say this is to say, one might think, very little; yet it remains profoundly contentious – the ground for endless battles. It is to suggest, merely, that at any time we come to the sphere of science with all our everyday pre-conceptions in place. At least in the world of human and social affairs, the nature of the empirical research which gets done and, in particular, the way it is broadcast and popularised, whether by scientists or their promoters, always reflects the assumptions and goals of the culture around it, or certain pockets of it. -

Hydra: a Powerful Biological Model∗

GENERAL ARTICLE Hydra: A Powerful Biological Model∗ Surendra Ghaskadbi Hydra, a freshwater diploblast, with a simple but defined body plan, an organized nervous system, and the presence of stem cells, is one of the oldest model organisms used in bi- ology. It exhibits many embryonic features even as an adult, a spectacular ability of regeneration, and lack of organismal aging. Hydra can provide insights into how complex animal forms evolved and is waiting to be better utilized in teaching. To understand biological processes, scientists often choose and Surendra Ghaskadbi is a use a small number of species based on the specific advantages developmental biologist each one of them offers. Such studies not only allow us to un- particularly interested in cell derstand how biological systems arose and function, but also pro- signaling during pattern vide insights into similar processes occurring in other species, formation and evolution of developmental mechanisms. sometimes even humans. Hydra, one of the oldest animals to Over the past two decades he have been used as a model system in biology, is a diploblast, i.e., has reintroduced hydra as a with a body made up of only two layers of cells, outer ectoderm model system for teaching and inner endoderm, which lives in freshwater bodies. It is a and research in India. Cnidarian with a simple but defined body plan. It is structurally more complex than sponges, which do not exhibit a defined body axis. Unlike us, who have three major body axes (dorsal-ventral, anterior-posterior, and left-right) and bilateral symmetry, hydra has an oral-aboral axis and radial symmetry. -

A Tribute to Lewis Wolpert and His Ideas on the 50Th Anniversary of the Publication of His Paper ‘Positional Information and the Spatial Pattern of Differentiation’

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review A Tribute to Lewis Wolpert and His Ideas on the 50th Anniversary of the Publication of His Paper ‘Positional Information and the Spatial Pattern of Differentiation’. Evidence for a Timing Mechanism for Setting Up the Vertebrate Anterior-Posterior (A-P) Axis Antony J. Durston Institute of Biology, University of Leiden, Sylvius Laboratory, Sylviusweg 72, 2333 BE Leiden, The Netherlands; [email protected] Received: 24 March 2020; Accepted: 3 April 2020; Published: 7 April 2020 Abstract: This article is a tribute to Lewis Wolpert and his ideas on the occasion of the recent 50th anniversary of the publication of his article ‘Positional Information and the Spatial Pattern of Differentiation’. This tribute relates to another one of his ideas: his early ‘Progress Zone’ timing model for limb development. Recent evidence is reviewed showing a mechanism sharing features with this model patterning the main body axis in early vertebrate development. This tribute celebrates the golden era of Developmental Biology. Keywords: hox genes; limb development; main body axis; timing; time space translation 1. Introduction: Lewis Wolpert and His Ideas Lewis Wolpert is a giant in the arena of scientific discovery. Together with others, including Francis Crick, Sydney Brenner, Brian Goodwin, Janni Nüsslein-Volhaard, Ed Lewis, the Physicist Morrel Cohen and the Mathematicians René Thom and Christopher Zeeman, his ideas and discoveries in a period starting in the 19600s helped establish that Developmental Biology is absolutely a key area of science. This was a period when ideas, rather than only technological developments, were recognised as the true currency of science. -

Historic Perspectives on Law & Science

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 2009 Historic Perspectives on Law & Science Robin Feldman UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Robin Feldman, Historic Perspectives on Law & Science, 2009 Stan. Tech. L. Rev. 1 (2009). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/157 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Author: Robin Cooper Feldman Source: Stanford Technology Law Review Citation: 2009 STAN. TECH. L. REV. 1 (2009). Title: Historic Perspectives on Law & Science Originally published in STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW. This article is reprinted with permission from STANFORD TECHNOLOGY LAW REVIEW and Stanford Law School. Robin Feldman: Historic Perspectives on Law & Science Stanford Technology Law Review Historic Perspectives on Law & Science ROBIN FELDMAN CITE AS: 2009 STAN. TECH. L. REV. 1 http://stlr.stanford.edu/pdf/feldman-historic-perspectives.pdf ¶1 Law has had a long and troubled relationship with science. The misuse of science within the legal realm, as well as our failed attempts to make law more scientific, are well documented.1 The cause of these problems, however, is less clear. ¶2 I would like to suggest that the unsatisfying relationship of law and science can be attributed, at least in part, to law‘s inadequate understanding of what constitutes science and law‘s inflated view of the potential benefits of science for law.