Sixth Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated Medicine in the Management of Chronic Illness: A

SB Brien, FL Bishop, K Riggs , et al Integrated medicine in the management of chronic illness: a qualitative study Sarah B Brien, Felicity L Bishop, Kirsty Riggs, David Stevenson, Victoria Freire and George Lewith INTRODUCTION ABSTRACT Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use Background is common in individuals with chronic health Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is problems; 70–90% 1 of patients with arthritis and 50% popular with patients, yet how patients use CAM in with irritable bowel syndrome 2 use CAM. Push and relation to orthodox medicine (OM) is poorly pull factors explain this phenomenon. Push factors understood. include the perceived failure 3 and adverse effects of Aim 3,4 To explore how patients integrate CAM and OM when orthodox medicine (OM), and dissatisfaction with its self-managing chronic illness. reliance on technology. 5 Pull factors include the Design of study perceived effectiveness of CAM, 3,6–8 and belief that Qualitative analysis of interviews. CAM offers a holistic 3,8,9 and patient-centred Method approach. 3,10 Semi-structured interviews were conducted with The majority of patients who use CAM integrate its individuals attending private CAM practices in the UK, 8,11 who had had a chronic benign condition for 12 months use with OM, but we know little about how patients and were using CAM alongside OM for more than manage chronic conditions when using both 3 months. Patients were selected to create a maximum approaches. Recent data suggest that people use variation sample. The interviews were analysed using and integrate CAM in different ways, as an alternative framework analysis. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

Building a Popular Science Library Collection for High School to Adult Learners: ISSUES and RECOMMENDED RESOURCES

Building a Popular Science Library Collection for High School to Adult Learners: ISSUES AND RECOMMENDED RESOURCES Gregg Sapp GREENWOOD PRESS BUILDING A POPULAR SCIENCE LIBRARY COLLECTION FOR HIGH SCHOOL TO ADULT LEARNERS Building a Popular Science Library Collection for High School to Adult Learners ISSUES AND RECOMMENDED RESOURCES Gregg Sapp GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sapp, Gregg. Building a popular science library collection for high school to adult learners : issues and recommended resources / Gregg Sapp. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0–313–28936–0 1. Libraries—United States—Special collections—Science. I. Title. Z688.S3S27 1995 025.2'75—dc20 94–46939 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 1995 by Gregg Sapp All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 94–46939 ISBN: 0–313–28936–0 First published in 1995 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 To Kelsey and Keegan, with love, I hope that you never stop learning. Contents Preface ix Part I: Scientific Information, Popular Science, and Lifelong Learning 1 -

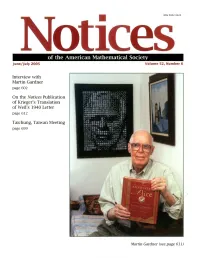

Interview with Martin Gardner Page 602

ISSN 0002-9920 of the American Mathematical Society june/july 2005 Volume 52, Number 6 Interview with Martin Gardner page 602 On the Notices Publication of Krieger's Translation of Weil' s 1940 Letter page 612 Taichung, Taiwan Meeting page 699 ., ' Martin Gardner (see page 611) AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY A Mathematical Gift, I, II, Ill The interplay between topology, functions, geometry, and algebra Shigeyuki Morita, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Japan, Koji Shiga, Yokohama, Japan, Toshikazu Sunada, Tohoku University, Sendai, Japan and Kenji Ueno, Kyoto University, Japan This three-volume set succinctly addresses the interplay between topology, functions, geometry, and algebra. Bringing the beauty and fun of mathematics to the classroom, the authors offer serious mathematics in an engaging style. Included are exercises and many figures illustrating the main concepts. It is suitable for advanced high-school students, graduate students, and researchers. The three-volume set includes A Mathematical Gift, I, II, and III. For a complete description, go to www.ams.org/bookstore-getitem/item=mawrld-gset Mathematical World, Volume 19; 2005; 136 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3282-4; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/19 Mathematical World, Volume 20; 2005; 128 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3283-2; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/20 Mathematical World, Volume 23; 2005; approximately 128 pages; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3284-0; List US$29;AII AMS members US$23; Order code MAWRLD/23 Set: Mathematical World, Volumes 19, 20, and 23; 2005; Softcover; ISBN 0-8218-3859-8; List US$75;AII AMS members US$60; Order code MAWRLD-GSET Also available as individual volumes .. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Rowlands, Barbara Ann (2015). The Emperor's New Clothes: Media Representations Of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 1990-2005. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/13706/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Emperor’s New Clothes: Media Representations of Complementary and Alternative Medicine: 1990-2005 BARBARA ANN ROWLANDS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by prior publication Department of Journalism City University London May 2015 VOLUME I: DISSERTATION CONTENTS Acknowledgements 4 Declaration 5 Abstract 6 Chapter -

Notes on Contributors

Archive for the Psychology of Religion 31 (2009) 387-389 brill.nl/arp Notes on Contributors Nina P. Azari earned a fi rst Ph.D. in cognitive psychology, and more recently, a second Ph.D. in Religious & Th eological Studies (dissertation: philosophical-theological analysis of neuroscientifi c study of religious experience). As an Alexander von Humboldt Fellow, Dr. Azari initiated a now long-standing collaboration with the University of Dusseldorf in Germany. She currently is Editor-In-Chief of a forthcoming Encyclopedia of Sciences and Religions (publisher: Springer). At present she is teaching in the Ridgeview Classical Schools, Fort Collins, Colorado. Her e-mail address is: [email protected]. Leslie J. Francis is Professor of Religions and Education in the Warwick Religions and Education Research Unit, University of Warwick, UK. His current research interests include the personality and work-related psychological health of the clergy. His e-mail address is: [email protected]. Thilo Hinterberger (Ph.D., PD) has studied physics at the University of Ulm, Germany. He received his Ph.D. at the University of Tübingen in 1999 in the fi eld of medical psy- chology. His major research focussed on the development of brain-computer interfaces for direct brain communication and psychophysiological research. He has completed his Habilitation (venia legendi) in Tübingen in the fi eld of neuro-computer science and behav- ioural neurobiology in 2007. From 2006 to 2008 he worked at the University of North- ampton in the fi eld of consciousness research. Currently, he is with the University Medical Center Freiburg/Germany continuing his work on the monitoring of higher states of consciousness. -

The Impact of NMR and MRI

WELLCOME WITNESSES TO TWENTIETH CENTURY MEDICINE _____________________________________________________________________________ MAKING THE HUMAN BODY TRANSPARENT: THE IMPACT OF NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE AND MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING _________________________________________________ RESEARCH IN GENERAL PRACTICE __________________________________ DRUGS IN PSYCHIATRIC PRACTICE ______________________ THE MRC COMMON COLD UNIT ____________________________________ WITNESS SEMINAR TRANSCRIPTS EDITED BY: E M TANSEY D A CHRISTIE L A REYNOLDS Volume Two – September 1998 ©The Trustee of the Wellcome Trust, London, 1998 First published by the Wellcome Trust, 1998 Occasional Publication no. 6, 1998 The Wellcome Trust is a registered charity, no. 210183. ISBN 978 186983 539 1 All volumes are freely available online at www.history.qmul.ac.uk/research/modbiomed/wellcome_witnesses/ Please cite as : Tansey E M, Christie D A, Reynolds L A. (eds) (1998) Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine, vol. 2. London: Wellcome Trust. Key Front cover photographs, L to R from the top: Professor Sir Godfrey Hounsfield, speaking (NMR) Professor Robert Steiner, Professor Sir Martin Wood, Professor Sir Rex Richards (NMR) Dr Alan Broadhurst, Dr David Healy (Psy) Dr James Lovelock, Mrs Betty Porterfield (CCU) Professor Alec Jenner (Psy) Professor David Hannay (GPs) Dr Donna Chaproniere (CCU) Professor Merton Sandler (Psy) Professor George Radda (NMR) Mr Keith (Tom) Thompson (CCU) Back cover photographs, L to R, from the top: Professor Hannah Steinberg, Professor -

Developmental Biology: a Very Short Introduction PDF Book

DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY: A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lewis Wolpert | 152 pages | 02 Sep 2011 | Oxford University Press | 9780199601196 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Developmental Biology: A Very Short Introduction PDF Book Vertebrates 3. Fashion is a gigantic global industry, generating some three hundred billion dollars in revenue every year, and playing a significant role in the economic, political, cultural and social lives of a vast international audience. For questions on access or troubleshooting, please check our FAQs , and if you can't find the answer there, please contact us. Get A Copy. There have been an increasing amount of studies with iPS cells since there seems to be ethical issues with using ES cells, despite these being harvested when an embryo could still split and turn into twins telling scientists it should not be classified as human life. Sort order. This Very Short Introduction decodes the key themes, signs, and symbols found in Christian art: the Eucharist, the image of the Crucifixion, the Virgin Mary, the Saints, Old and New Testament narrative imagery, and iconography. Advanced Search. From a single cell--a fertilized egg--comes an elephant, a fly, or a human. Search Items. Members save with free shipping everyday! Details if other :. Evolutionary Genetics: Concepts, Analysis, and Practice. In this Very Short Introduction, renowned scientist Lewis Wolpert shows how the field of developmental biology seeks to answer these profound questions. See 1 question about Developmental Biology…. Request Examination Copy. For the last A distinguished developmental biologist himself, Wolpert offers a concise and highly readable account of what we now know about development, discussing the first vital steps of growth, the patterning created by Hox genes and the development of form, embryonic stem cells, the timing of gene expression and its management, chemical signaling, and growth. -

Varieties of Modules: Kinds, Levels, Origins, and Behaviors RASMUS G

116JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL R.G. WINTHER ZOOLOGY (MOL DEV EVOL) 291:116–129 (2001) Varieties of Modules: Kinds, Levels, Origins, and Behaviors RASMUS G. WINTHER* Department of History and Philosophy of Science, and Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana 47405 ABSTRACT This article began as a review of a conference, organized by Gerhard Schlosser, entitled “Modularity in Development and Evolution.” The conference was held at, and sponsored by, the Hanse Wissenschaftskolleg in Delmenhorst, Germany in May, 2000. The article subse- quently metamorphosed into a literature and concept review as well as an analysis of the differ- ences in current perspectives on modularity. Consequently, I refer to general aspects of the conference but do not review particular presentations. I divide modules into three kinds: struc- tural, developmental, and physiological. Every module fulfills none, one, or multiple functional roles. Two further orthogonal distinctions are important in this context: module-kinds versus mod- ule-variants-of-a-kind and reproducer versus nonreproducer modules. I review criteria for indi- viduation of modules and mechanisms for the phylogenetic origin of modularity. I discuss conceptual and methodological differences between developmental and evolutionary biologists, in particular the difference between integration and competition perspectives on individualization and modular behavior. The variety in views regarding modularity presents challenges that require resolution in order to attain a comprehensive, -

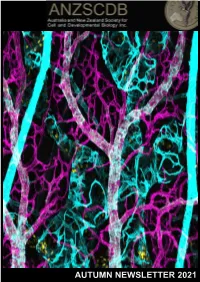

Autumn Newsletter 2021

AUTUMN NEWSLETTER 2021 Autumn NEWSLETTER – March 2021 Dear ANZSCDB members, ANZSCDB welcomes you to 2021, the year we emerge from the shadow of COVID-19 and work towards a return to the ‘normal’ routines of science, academia, research and industry. The local and global emergence from the pandemic is perhaps slower, more sporadic and less ‘normal’ than is ideal, and it still comes with significant hardship for many. However, hope abounds. We at ANZSCDB are committed to reconnecting with our members this year through a series of newsletters, satellite meetings and other forums, as detailed in this newsletter. While travel is still impeded, in-person conferences remain impractical and so we will be reaching out through locally held meetings which offer bi-national online access. We really hope that members will reach out and interact through these satellite meetings. Our interactions and shared science this year are critical to seed the planning of future meetings and conferences. Next year is the target for returning to full, in-person meetings, notably with ComBio planned for a return in 2022. The exceptional dedication and hard work of our Executive, Committees and State representatives will be on display through this year, ‘making it happen’ for all of us. Many are still in the midst of grant writing season and/or starting the year’s teaching. Both can be stressful for many reasons at this time, including our dwindling levels of government research funding and pressures on university budgets. I hope that this year also sees some improvement in this landscape. A reflection on the how the pandemic has unfolded and In this issue the world’s response over the past year, has profound missives for scientific research. -

Holistic Healthcare Is Available Through EBSCO, a World Leader in Accessible Academic Library Databases

JOURNAL OF holistic Contents healthcare Editorial. 2 News review. 3 ISSN 1743-9493 General practice – the future is integrated . 5 Michael Dixon Published by Complementary medicine helps patients . 7 British Holistic Medical Association The campaign against CAM – a reason to be proud . 8 PO Box 371 Harald Walach Bridgwater High costs, large disease burden . 14 Somerset TA6 9BG Jonathan Lord Tel:01278 722000 Email: [email protected] Challenges in interpreting and applying the evidence for complementary, alternative and www.bhma.org integrated medicine. 16 Catherine Zollman, Hugh MacPherson Reg. Charity No. 289459 Vested interests and the greater good . 23 Editor-in-chief William House David Peters More harm than good? . 26 [email protected] George Lewith Integration, long term disease and creating a Editorial Board sustainable NHS. 29 Jan Alcoe, Richard James, David Peters Willliam House Approaches to healthcare: connectedness and spirituality . 32 Editor Denise Peerbhoy Edwina Rowling [email protected] On becoming a ‘recovery ally’ for people with depression . 38 Administrator Damien Ridge Di Brown Nursing in partnership with patients means [email protected] embracing integrated healthcare. 42 Donna Kinnair Advertising Rates An integrated approach to gynaecology. 44 1/4 page £110; 1/2 page £185; Michael Dooley full page £330; loose inserts £120. The challenge of obesity . 48 Rates are exclusive of origination Chris Drinkwater where applicable.To advertise, call Di Brown on 01278 722000 Students’ health matters . 51 or email [email protected] Krisna Steedhar From the frontline . 53 Products and services offered by William House advertisers in these pages are not Research summaries . 54 necessarily endorsed by the BHMA. -

Alister Mcgrath

O DEUS DE DAWKINS ALISTER MCGRATH TRADUÇÃO Sueli Saraiva Shedd publicações Literatura Que Edifica <.genes, memes e o sentido da vida.> © 2007 B Y ALISTER MCGRATH This edition is published by arrangement with Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford. Translated by Shedd Publicações from the original English language version. Responsabilit y of the accuracy of the translation rests solely with Shedd Publicações and is not the responsibiiity of Blackwell Publishing Ltd. a 1 Edição - Agosto de 2008 Publicado no Brasil com a devida autorização e com todos os direitos reservados por SHEDD PUBLICAÇÕES LTDA -ME. Rua São Nazário, 30, Sto Amaro, São Paulo-SP - 04741-150 Tel. (011) 5521-1924 - Vendas (011) 5666-1911 Email: [email protected] - VAVw.sheddpublicacoes.com.br Proibida a reprodução por quaisquer meios (mecânicos, eletrônicos, xerográficos, fotográficos, gravação, estocagem em banco de dados, etc), a não ser em citações breves com indicação de fonte. Portuguese language - Printed in Brazil / Impresso no Brasil ISBN 978-85-88315-70-9 TRADUÇÃO : Sueli Saraiva REVISÃO: Regina Aranha DIAGRAMAÇÃO: Edmilson Frazão Bizerra CAPA : Júlio Carvalho Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) (Câmara Brasileira do Livro, SP, Brasil) McGrath, Alister, 1953- O deus de DawKins : genes, memes e o sentido da vida / Alister McGrath ; tradução Sueli Saraiva. - São Paulo : Shedd Publicações, 2008. Título original: DawKins' God : genes, memes and the meaning of life. Bibliografia. ISBN: 978-85-88315-70-9 1. Apologética 2. DawKins, Richard, 1941 -I. Título. 08-07830 CDD- 261.55 índices para catálogo sistemático: 1. Universo : Criação : Ciência e fé 261.55 Sum ário Encontro com Dawkins: um relato pessoal 7 1.