The Authority of Women Hosts of Early Christian Gatherings in the First and Second Centuries C.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Letter of Paul the Apostle of YHWH to Philemon

Paul’s Letter to Philemon Page 1 of 194 The Letter of Paul the Apostle of YHWH to Philemon (A Commentary) Paul’s Letter to Philemon Page 2 of 194 First Edition in English: 13 August 2021 Published by www.David4Messiah.com Apollo Beach, Florida, USA Dr. David d'Albany Copy freely without profit. Distribute freely without profit. Share freely without profit. Paul’s Letter to Philemon Page 3 of 194 Content Page The Text in Aramaic Estragelo 4 The Text in Aramaic AENT 5 The Text in English 6-9 Eleven Persons 10 - 13 Timothy 14 - 22 Philemon 23 - 24 Apphia 25 Archippus 26 - 27 Onesimus 28 - 33 Epaphras 34 - 35 Mark 36 - 45 Aristarchus 46 Demas 47 - 48 Luke 49 - 53 Paul 54 - 60 Commentary verse by verse 61 - 193 The Priestly Benediction 194 Paul’s Letter to Philemon Page 4 of 194 The Text in the original Estrangelo script Paul’s Letter to Philemon Page 5 of 194 The Text in the original Western Aramaic Text (from AENT Aramaic English New Testament) Paul’s Letter to Philemon Page 6 of 194 THE LETTER OF PAUL TO PHILEMON 1. PAUL, a prisoner of Jesus Yeshua the Mashiyach Messiah (the Anointed One), and Timothy, a brother; to the dearly beloved Philemon, a laborer with us, 2. and to our dearly beloved Apphia, and to Archippus a laborer (worker) with us, and to the assembly (ekklyssia) in your house. 3. Grace be with you and peace from God our Father and from our Lord Jesus the Messiah (the Anointed One). -

1 on the Church Dr. Stan Fleming Introduction the Word Church

On The Church Dr. Stan Fleming Introduction The word church: Somebody once said, “The world at its worst needs the church at its best.” 1 I. What is the Church? A. If you look up the word in a dictionary it might be defined as “a building that is used for Christian religious services”. The Greek word Kruiakon means “the Lord’s house” and the word church is associated with that, but it is also associated with the Greek word Ekklesia which means “the called out ones”. In the country of Greece, Ekklesia meant the idea of citizens called to assemble for legislative or other community purposes. 2 B. Strong’s (1577) ekklesia; a calling out , a popular meeting, especially a religious congregation (Jewish synagogue or Christian community of members on earth or saints in heaven or both): - assembly, church. C. Current statistics on congregations and denominations 1. 4,629,000 Christian congregations 2. 44,000 denominations D. Mentioned in the New Testament 1. Church – 80 times 2. Churches – 37 times E. Old Testament concepts 1. Old Testament concepts: assembly, congregation; though the word synagogue is a New Testament word, the concept of the meeting places of Jews is in the Old Testament (Psalm 74:8) and is still used by Jews to this day. II. The New Testament and Basic Ideas about the Church A. Jesus introduces and concludes the use of the word church : 1. Matthew 16:18 “I will build My church, and the gates of Hades shall not prevail against it.” 2. Revelation 22:16 “I, Jesus, have sent My angel to testify to you these things in the churches. -

Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews

Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews Length of Time # Book Chapters Listening / Reading 1 Matthew 28 2 hours 20 minutes 2 Mark 16 1 hour 25 minutes 3 Luke 24 2 hours 25 minutes 4 John 21 1 hour 55 minutes 5 Acts 28 2 hours 15 minutes 6 Romans 16 1 hour 5 minutes 7 1 Corinthians 16 1 hour 8 2 Corinthians 13 40 minutes 9 Galatians 6 21 minutes 10 Ephesians 6 19 minutes 11 Philippians 4 14 minutes 12 Colossians 4 13 minutes 13 1 Thessalonians 5 12 minutes 14 2 Thessalonians 3 7 minutes 15 1 Timothy 6 16 minutes 16 2 Timothy 4 12 minutes 17 Titus 3 7 minutes 18 Philemon 1 3 minutes 19 Hebrews 13 45 minutes 20 James 5 16 minutes 21 1 Peter 5 16 minutes 22 2 Peter 3 11 minutes 23 1 John 5 16 minutes 24 2 John 1 2 minutes 25 3 John 1 2 minutes 26 Jude 1 4 minutes 27 Revelation 22 1 hour 15 minutes Berean Digest Walking Thru the Bible Tavares D. Mathews Matthew Author: Matthew Date: AD 50-60 Audience: Jewish Christians in Palestine Chapters: 28 Theme: Jesus is the Christ (Messiah), King of the Jews People: Joseph, Mary (mother of Jesus), Wise men (magi), Herod the Great, John the Baptizer, Simon Peter, Andrew, James, John, Matthew, Herod Antipas, Herodias, Caiaphas, Mary of Bethany, Pilate, Barabbas, Simon of Cyrene, Judas Iscariot, Mary Magdalene, Joseph of Arimathea Places: Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Egypt, Nazareth, Judean wilderness, Jordan River, Capernaum, Sea of Galilee, Decapolis, Gadarenes, Chorazin, Bethsaida, Tyre, Sidon, Caesarea Philippi, Jericho, Bethany, Bethphage, Gethsemane, Cyrene, Golgotha, Arimathea. -

Christian Origins Seminar Spring Meeting 2010

Spring Meeting 2010 Ballot 1 Story and Ritual as the Foundation of Nations Helmut Koester Report from the Jesus Seminar Q1 Story and ritual are the religio-political foundations of the on Christian Origins founding of nations in Antiquity. This is demonstrated in brief survey of the founding of the nations of the Hellenes, of Israel, and of imperial Rome. Fellows 0.88 Red 0.75 %R 0.20 %P 0.00 %G 0.05 %B Associates 0.86 Red 0.68 %R 0.27 %P 0.00 %G 0.05 %B Q2 The beginnings of the early Christian movement are Stephen J. Patterson, Chair political rather than “religious”; Paul wants to create a new nation of justice and equality opposed to the unjust hierarchical establishment of imperial Rome. This is dis- cussed with reference to John the Baptist, Jesus and Paul. Fellows 0.58 Pink 0.15 %R 0.55 %P 0.20 %G 0.10 %B Associates 0.61 Pink 0.18 %R 0.45 %P 0.36 %G 0.00 %B The Jesus Seminar on Christian Origins convened on Q3 As early Christians churches tried to find their place as a March 19–20 to consider some remaining issues associ- “religion” in the Greco-Roman world they soon began to become conform with the morality and citizenship of the ated with Antioch, and to air out some long-standing ques- Roman society. tions associated with the work of the Jesus Seminar. It was a Fellows 0.78 Red 0.50 %R 0.35 %P 0.15 %G 0.00 %B remarkable meeting. -

On Putting Paul in His Place Author(S): Victor Paul Furnish Reviewed Work(S): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol

On Putting Paul in His Place Author(s): Victor Paul Furnish Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 113, No. 1 (Spring, 1994), pp. 3-17 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3266307 . Accessed: 06/04/2012 10:44 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JBL 113/1(1994) 3-17 ON PUTTING PAUL IN HIS PLACE* VICTOR PAUL FURNISH Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX 75275 Paul is easily the most accessible figure in first-century Christianity, arguably the most important; and, of course, he has been the subject of countless scholarly studies. Yet he remains, in many respects, an enigmatic figure. He seems to have been a puzzle even to his contemporaries, perhaps no less to many of his fellow believers in the church than to most of his former colleagues in the synagogue. And over time, also his letters became a problem, as attested by that oft-quoted remark in 2 Peter, "there are some things in them hard to understand" (3:16). -

1 the Supremacy of Christ the Gospel Encourages Participation

The Supremacy of Christ The Gospel Encourages Participation Colossians 4:7-18 Introduction Today is our final message on the letter to the Colossians and the Supremacy of Christ. As we learned Colossae was a city in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), situated in the Lycus River valley about 110 miles south-east of Ephesus. It was a prominent city in classical Greek times because of its importance in producing dyed wool and its location on the trade route between Ephesus and the East. It was close to two other cities, Hierapolis and Laodicea, both mentioned in the New Testament. These two cities gradually eclipsed Colossae, and by the time Paul wrote this letter to the Colossians, it was a small and relatively unimportant city. Paul didn’t found the Colossian church, it was one of the churches evangelized by Epaphras, a disciple of Paul's (Col.4.12-13). Epaphras had become alarmed about a cult that was developing in the Colossian church, and since Paul was imprisoned in Rome, he went there to consult with him. Paul agreed the situation was serious and decided to write a letter to the Colossians. Paul begins his letter by thanking God for the Colossians and their decision to become followers of Christ. He commends them for receiving the “gospel” (the good news that Jesus is the Messiah and that through His death, we can be forgiven and reconciled to God. Paul also rejoices that the “gospel” is changing their lives. By accepting Jesus and receiving Eternal Life, the Holy Spirit has given them a sense of inner peace and new hope for their lives. -

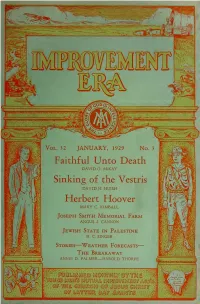

The Improvement Era — — —

rC >s -&SS, , l 7 *UV«UUAWB.i^Wr-W7JJ.WS*J!A-WJJ. iWi JJ *t'W. u Tfi.uijiu.il mpmwiwfww' w«A»»!»m»!ww»mwwT»«n"»WBW^ Vol. 32 JANUARY, 1929 No. 3 Faithful Unto Death DAVID O. McKAY Sinking of the Vestris DAVID H. HUISH Herbert Hoover mary c. kimball Joseph Smith Memorial Farm angus j. cannon Jewish State in Palestine h. c. singer Stories—Weather Forecasts— The Breakaway annie d. palmer—harold thorpe jtM^iiinMiannriiiiiniiir - ' . ' - . T T . V. , ) . J *-^ : : |kv.-'.-v. :' op !^TW. ®^:\^.i^TOH(.Uiji SOUTHERN PACIFIC LINES OFFER SPECIAL WINTER EXCURSION FARES FROM SALT LAKE CITY OR Oi TO LOS ANGELES AND RETURN BOTH WAYS VIA SAN FRANCISCO $50.50 TO LOS ANGELES VIA SAN FRANCISCO RETURNING DIRECT OR ROUTE REVERSED $58.00 Proportionately low fares from all other points in UTAH, IDAHO and MONTANA STOPOVERS ALLOWED AT ALL POINTS TICKETS ON SALE DAILY COMMENCING OCTOBER 1ST FINAL RETURN LIMIT 8 MONTHS FROM DATE OF SALE For further information CALL, WRITE or PHONE PRESS BANCROFT, GENERAL AGENT 41 SO. MAIN ST. SALT LAKE CITY PHONE WASATCH 3008—3078 Never Too Busy For Personal Attention- —OUR STUDENTS' SUCCESS IS OUR BIGGEST ASSET L. D. S. Business College ENROLL ANY MONDAY WHEN WRITING TO ADVERTISERS PLEASE MENTION THE IMPROVEMENT ERA — — — . Home Electric Service— SAVES LABOR, TIME, ENERGY, WORRY AND MONEY —and makes the home a pleasanter and happier place to LIVE in. We invite you to come to any of our stores to inspect the large variety of electric servants avail- able. There are certainly some that you will want. -

Study Guide - Pt

The Story Houston - 8|18|19 - Sermon Study Guide - Pt. 3: The Time Jesus Called a Woman a Dog Pastor Eric Huffman - Fb/Ig @pastorerichuffman | Twitter @ericthestory | Email [email protected] Welcome to The Story... and to our August sermon series called Knowing Her Place. All month long, we’re exploring every detail of several personal encounters Jesus had with women from all walks of life. You might be surprised to learn how Jesus understood the role of women in his life and ministry, and what that might mean for us today. Before We Begin... What are the differences between ‘Christian complementarianism’ and ‘Christian egalitarianism’? What is the biblical basis for each worldview, and where does each fall short? Describe the alternative vision of femininity, masculinity, and gender roles presented in the Bible? Where is this alternative presented throughout Jesus’ life and ministry? That Time Jesus Called a Woman a Dog Today’s scripture tells about the time Jesus encountered a foreign woman whose daughter was struggling. Matthew 15:21-28 21 Jesus left that place and went away to the district of Tyre and Sidon. 22 Just then a Canaanite woman from that region came out and started shouting, “Have mercy on me, Lord, Son of David; my daughter is tormented by a demon.” 23 But he did not answer her at all. And his disciples came and urged him, saying, “Send her away, for she keeps shouting after us.” 24 He answered, “I was sent only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.” 25 But she came and knelt before him, saying, “Lord, help me.” 26 He answered, “It is not fair to take the children’s food and throw it to the dogs.” 27 She said, “Yes, Lord, yet even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table.” 28 Then Jesus answered her, “Woman, great is your faith! Let it be done for you as you wish.” And her daughter was healed instantly. -

Miranda Threlfall-Holmes Is Vicar of Belmont and Pittington in the Diocese of Durham, and an Honorary Fellow of Durham University

Miranda Threlfall-Holmes is Vicar of Belmont and Pittington in the Diocese of Durham, and an honorary fellow of Durham University. Previously, she was Chaplain and Solway Fellow of University College, Durham, and a member of the Church of England General Synod. She has first-class degrees in both history (from Cambridge) and theology (from Durham), and a PhD in medieval history. She trained for ordination at Cranmer Hall, Durham, and was then a curate at St Gabriel’s church in Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne. She has taught history at Durham and Newcastle universities, as well as for the North East Institute for Theological Education, the Lindisfarne Regional Training Partnership and Cranmer Hall. As a historian and theologian, she has written and published extensively in both the aca- demic and popular media. Her doctoral thesis, Monks and Markets: Durham Cathedral Priory 1460–1520, was published by Oxford University Press in 2005, and she co-edited Being a Chaplain with Mark Newitt in 2011 (published by SPCK). She has also contributed to the Church Times, The Guardian and Reuters. THE essential historY OF christianitY MIRANDA THRELFALL-HOLMES First published in Great Britain in 2012 Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge 36 Causton Street London SW1P 4ST www.spckpublishing.co.uk Copyright © Miranda Threlfall-Holmes 2012 Miranda Threlfall-Holmes has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

(In Spirit): Wealth and Poverty in the Writings of the Greek Christian Fathers of the Second Century

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2021 Blessed Are the Poor (in Spirit): Wealth and Poverty in the Writings of the Greek Christian Fathers of the Second Century Jacob D. Hayden Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Hayden, Jacob D., "Blessed Are the Poor (in Spirit): Wealth and Poverty in the Writings of the Greek Christian Fathers of the Second Century" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8181. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8181 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLESSED ARE THE POOR (IN SPIRIT): WEALTH AND POVERTY IN THE WRITINGS OF THE GREEK CHRISTIAN FATHERS OF THE SECOND CENTURY by Jacob D. Hayden A thesis submitted in partiaL fuLfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Ancient Languages and CuLtures Approved: _______________________ _____________________ Mark Damen, Ph.D. Norman Jones, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member _______________________ ______________________ Eliza Rosenberg, Ph.D. Patrick Q. Mason, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member ________________________________ D. Richard CutLer, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © Jacob D. Hayden 2021 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Blessed Are the Poor (in Spirit): Wealthy and Poverty in the Writings of the Greek Christian Fathers of the Second Century by Jacob D. -

Religion and the Greeks Free Download

RELIGION AND THE GREEKS FREE DOWNLOAD Robert Garland | 128 pages | 01 Apr 2013 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781853994098 | English | London, United Kingdom Greek religion Politics Constitution Constitutional amendments, Constitutions, Supreme Special Court. One would never finish listing all the gods that Rome added to the gods of Greece; never did a Greek or Religion and the Greeks village have so Religion and the Greeks. The first Greeks had seen the gods travel and live among them. List of ancient Greeks. They wanted gods of truly divine nature, gods disengaged from matter. Thus perished three Decius, all three of them consuls; such were the voluntary sacrifices that Rome admired, and yet it did not order them. Although pride and vanity were not considered sins themselves, the Greeks emphasized moderation. While much religious practice was, as well as personal, aimed at developing solidarity within the polisa number of important sanctuaries developed a "Panhellenic" status, drawing visitors from Religion and the Greeks over the Greek world. Korean shamanism Cheondoism Jeungsanism. This process was certainly under way by the 9th century, and probably started earlier. However, there are many fewer followers than Greek Orthodox Christianity. The Trojan Palladiumfamous from the myths of the Epic Cycle and supposedly ending up in Rome, was one of these. Overall, the Ancient Greeks used their religion to help explain the world around them. Generally, the Greeks put more faith in observing the behavior of birds. For example, most households had an alter dedicated to Hestia, the goddess of the hearth. The name of Cassandra is famous, and Cicero Religion and the Greeks why this princess in a furor discovered the future, while Priam her father, in the tranquility of his reason, saw nothing. -

ABSTRACT Reading Dreams: an Audience-Critical Approach to the Dreams in the Gospel of Matthew Derek S. Dodson, B.A., M.Div

ABSTRACT Reading Dreams: An Audience-Critical Approach to the Dreams in the Gospel of Matthew Derek S. Dodson, B.A., M.Div. Mentor: Charles H. Talbert, Ph.D. This dissertation seeks to read the dreams in the Gospel of Matthew (1:18b-25; 2:12, 13-15, 19-21, 22; 27:19) as the authorial audience. This approach requires an understanding of the social and literary character of dreams in the Greco-Roman world. Chapter Two describes the social function of dreams, noting that dreams constituted one form of divination in the ancient world. This religious character of dreams is further described by considering the practice of dreams in ancient magic and Greco-Roman cults as well as the role of dream interpreters. This chapter also includes a sketch of the theories and classification of dreams that developed in the ancient world. Chapters Three and Four demonstrate the literary dimensions of dreams in Greco-Roman literature. I refer to this literary character of dreams as the “script of dreams;” that is, there is a “script” (form) to how one narrates or reports dreams in ancient literature, and at the same time dreams could be adapted, or “scripted,” for a range of literary functions. This exploration of the literary representation of dreams is nuanced by considering the literary form of dreams, dreams in the Greco-Roman rhetorical tradition, the inventiveness of literary dreams, and the literary function of dreams. In light of the social and literary contexts of dreams, the dreams of the Gospel of Matthew are analyzed in Chapter Five.