Narrative of Richard Jones, Excerpts: a Boatman on the Broad River, 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Publication of the Virginia Canals and Navigations Society Summer 2007 Volume 28, Issue 2 2

The Tiller A Publication of the Virginia Canals and Navigations Society Summer 2007 Volume 28, Issue 2 2 2 The Tiller President Watercraft Operations Dan River Robert M. “Buddy” High William E. Turnage Bob Carter General Delivery 6301 Old Wrexham Pl. 1141 Irvin Farm Rd. Valentine, VA 23887 Chesterfield, VA 23832 Reedsville, NC 27320 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (434) 577-2427 Board of Trustees Eastern Virginia Vice-President Natalie Ross Kyle Schilling vacant PO Box 8224 30 Brook Crest Ln. Charlottesville, VA 22906 Stafford, VA 22554 Recording Secretary [email protected] (434) 577-2427 Jean High Term: 2007-2012 General Delivery Northern Virginia Valentine, VA 23887 Douglas MacLeod Myles “Mike” R. Howlett [email protected] PO Box 3119 6826 Rosemont Dr. Lynchburg, VA 24503 McLean, VA 22101 Corresponding Secretary [email protected] [email protected] Lynn Howlett Term: 2006-2011 6826 Rosemont Dr. Richmond William E. Trout, III, Ph.D. McLean, VA 22101 Vacant [email protected] 35 Towana Rd. Richmond, VA 23226 [email protected] Rivanna River Treasurer Term: 2005-2010 Peter C. Runge Atwill R. Melton 119 Harvest Dr. 1587 Larkin Mountain Rd. William E. Turnage Charlottesville, VA 22903 Amherst, VA 24521 See Watercraft Operations [email protected] [email protected] Term: 2004-2009 Southeast Virginia Archivist/Historian Richard Davis George Ramsey Phillip Eckman See VCNS Sales 2827 Windjammer Rd. 902 Park Ave. Term: 2003-2008 Colonial Heights, VA 23834 Suffolk, VA 23435 [email protected] [email protected] Webmaster District Directors Staunton River George Ramsey, Jr. Roy Barnard [email protected] Appomattox River 94 Batteau Rd. -

Virginia Antebellum (1800 to 1860)

Virginia Antebellum (1800 to 1860) Virginia History Series #5-08 © 2008 “Antebellum” is a Latin word meaning "before war" (“ante” means before and “bellum” means war). In United States History, the term “antebellum” often refers to the period of increasing sectionalism leading up to the American Civil War. 1800 to 1860 In the context of this presentation, the “Antebellum Period” is considered to have begun with the rancorous election of Thomas Jefferson as President in 1800 and continued up until the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, the election of Abraham Lincoln, and the start of the Civil War in 1861. People of Virginia Census Pop Rank in The number of people residing Year x1000 States in the Commonwealth of Virginia increased by 77% 1800 900 1st from 1800 to 1860. 1810 984 1st 1820 1,000 2nd 1830 1,220 3rd In this period, Virginia’s 1840 1,250 4th population grew slower than 1850 1,500 4th other States; and, its ranking 1860 1,596 5th in population among the states actually declined from 1st to 5th by 1860. 92 Counties in Virginia by 1800 (Including Appalachian Plateau, Valley & Ridge, Blue Ridge Mountain, and other areas in present-day West Virginia) County Formation 1800-1890 Counties are formed to make local government more available to citizens who need access to courts, land offices, etc. Larger counties are sub-divided into smaller & smaller areas until county offices are close enough to support citizen access. Except in the “western” part of the State, most Virginia county borders are stable by 1890. -

Rivers of the Richmond Region

Chickahominy River 21 Cartersville Boat Ramp 35 22nd Street 47 Dutch Gap Boat Landing 61 Appomattox River Canoe (Cumberland County) This concrete ramp adjacent to the Route (City of Richmond) This park entry point offers pedestrian and (Chesterfield County) This concrete ramp near Henricus Launch 45 bridge offers access for launching boats from the south bicycle access to the south side of Belle Isle via short walk to Historical Park offers access for launching boats from the Public Access Points 7 Chickahominy Swamp / (Chesterfield County) Located just below the dam, this parking bank of the river. Parking is only for vehicles associated with trails and a service bridge. A mountain bike trail links the south bank of the river. Located adjacent to the Dutch Gap area and boat slide for small non-powered craft offer access Grapevine Bridge Put-In fishing or boating. (dgif.virginia.gov/boating) Riverbed Trail to the Buttermilk Trail. The 45-car parking lot Conservation Area, the site is jointly maintained by DGIF and to fishing, picnicking, and hiking. The site serves as the Park or public open space RIVERS (Henrico County) This launch site features benches, picnic table, Cartersville Rd.; opposite intersection with High St. (23027) is often closed. (jamesriverpark.org) Chesterfield County. trailhead for the John J. Radcliffe Conservation Area’s 87 acres, 2101 Riverside Dr. (23225) (dgif.virginia.gov/boating) interpretive signage, and a put-in for canoes and kayaks to 1.5-mile nature trail, and over 500 feet of elevated boardwalk. explore the upper area of the Chickahominy. There is plenty of 22 Westview Boat Ramp 441 Coxendale Rd. -

THE MARSHALL Expedition a Modern Tale of Historical Adventure

Wonderful West Virginia Magazine 4 WONDERFUL WEST VIRGINIA | JUNE 2015 Wonderful West Virginia Magazine THE MARSHALL Expedition A modern tale of historical adventure WRITTEN BY ERIC J. WALLACE PHOTOGRAPHED BY WESLEY ANDREWS WONDERFULWV.COM 5 Wonderful West Virginia Magazine magine yourself poised at the stern of a 47-foot- long wooden boat, arms braced about the rudder’s wooden handle, shouting commands to your crew as you crash through the 10-foot waves of the New River Gorge, seeking to steer your vessel through the treacherous Class IV rapids. If successful, you’ll become the first bateau crew to have done so in more than 125 years. Such was the experience of National Geographic Young Explorer Grant recipient Andrew Shaw in 2012. But how did Shaw get there? The tale begins more than 200 years ago, at the dawn of the founding of Ithe United States of America. In the late 18th century, the midwestern territories were highly contested. If Virginia was to secure its status as the New World’s dominant economic hub, the colony would need to expand its shipping capabilities westward. Future- President George Washington hatched a plan, envision- ing a vast canal system connecting the colonies’ major shipping corridor, the James River, with that of the distant and disputed frontier, the mighty Mississippi. “It was a toss-up as to whether the French, British, Spaniards, and even Russians would end up controlling the region,” says Bill Trout, founder of the Virginia Canal Society. “It was Washington’s viewpoint that, to control those territories, the colonies would have to establish strong economic ties with its settlers.” That would mean providing them with easy transport for goods to and from the eastern seaboard. -

Carving a Fourth Seacoast Dreams of a Seaway

Chapter 1 CARVING A FOURTH SEACOAST DREAMS OF A SEAWAY n 1957 legendary CBS newsman Walter Cronkite—lauded as the most trusted man in America—stared into the camera and told viewers that Ithe “greatest engineering feat of our time” was under way. He wasn’t talking about the Soviet Union rocketing the stray dog Laika into orbit, or that year’s development of the first wearable pacemaker, or the recent opening of the United States’ first commercial atomic power plant. He was talking about humans “conquering” nature on a scale and in a fashion never before attempted. “Right now the greatest concentration of heavy machinery ever assembled—over 3,000 pieces of equipment—are at work on one of the greatest projects in the history of mankind,” Cronkite said as he stood in front of a map of the deep blue Great Lakes and the even deeper blue Atlantic Ocean. He fixed his eyes on the camera and spoke boldly of a construction project that would, in effect, do no less than move the Atlantic Ocean more than 1,000 miles inland, to the middle of North America. The idea was to scrape and blast a navigation channel along and through the shallow, tumbling St. Lawrence River that flows from the Property of W. W. Norton & Company DeathAndLifeOfTheGreatLakes_txt_final.indd 3 12/15/16 2:36 PM 4 THE DEATH AND LIFE OF THE GREAT LAKES Great Lakes out to the ocean in a manner that would allow giant freighters to steam from the East Coast into the five massive freshwater inland seas. -

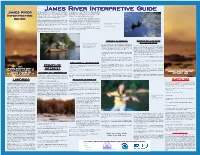

James Riv James River Interpretive Guide

JamesJames RivRiverer IntIntererprpreetivtivee GuideGuide to Robious Landing on river right; 5 miles to Bosher’s dam 9. At mile 20.5, on river right, is the Cartersville Boat James River portage, on river left. From the dam, it is 1 mile to Landing. The river gage is on river left. Also, there are Huguenot Flatwater Park, 2 miles to Pony Pasture Rapids stone piers of an early bridge that served wagons going Interpretive Park and 4½ miles to Reedy Creek, all on river right. The between Cumberland and Goochland counties. last take-out before Class 3 and up rapids. Guide 10. At mile 21, on river left, is the Cartersville Connection Guide Robious Landing Park is just behind James River High Lock. This lowered boats from the canal into the river so School, off Rt. 711, 3 miles from Rt. 150. This is a large they could dock at Cartersville. A short way down stream park with a slide launch that will accommodate canoes, is the Connection Dam that created slack water up to Fishing along the James River is a kayaks, and rowing shells. Both a picnic shelter and Cartersville for canal boats using the lock. popular activity. restrooms are available all year. Photo: David Euerette © 11. At mile 21.5, on river right, Muddy Creek marks the Huguenot Flatwater Park, on river right, (part of James boundary between Cumberland County to the west and River Park System) has canoe access steps. A portable Powhatan County to the east. toilet is available from mid-May to October. MAIDEN’S TO WATKINS WATKINS TO HUGUENOT Batteaus travel the James River FLATWATER PARK 24. -

Slavery and the African Colonization Movement in Southwestern Virginia Author(S): ERIC BURIN Source: Appalachian Journal, Vol

Appalachian Journal Appalachian State University A Manumission in the Mountains: Slavery and the African Colonization Movement in Southwestern Virginia Author(s): ERIC BURIN Source: Appalachian Journal, Vol. 33, No. 2 (WINTER 2006), pp. 164-186 Published by: Appalachian Journal and Appalachian State University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40934746 Accessed: 13-11-2018 18:14 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Appalachian Journal, Appalachian State University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Appalachian Journal This content downloaded from 199.111.241.11 on Tue, 13 Nov 2018 18:14:52 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms History ERIC BURIN A Manumission in the Mountains: Slavery and the African Colonization Movement in Southwestern Virginia Eric Burin is an Associate Professor of History at the University of North Dakota and author of Slavery and the Peculiar Solution: A History of the American Colonization Society (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005). In late August, 1847, an auspicious letter landed on the desk of William McLain, the secretary of the American Colonization Society (ACS). The letter was from Nicholas Chevalier, a 37-year-old Presbyterian pastor from Christiansburg, a town in mountainous southwestern Virginia. -

The Smithfield Review, Volume VI, 2002, Crawford

A James River Batteau, from a painting by Jon Roark. (Copied from A Guide to Historic Salem, vol. 3, no. 2 (Summer 1997) Batteaux* on Virginia's Rivers Dan Crawford Dan Crawford is the lead interpreter of the batteau site at Virginia's Explore Park, off the Blue Ridge Parkway in Roanoke County. He has 25 years of experience on and around salt water, including working on museum s4uare- rigged ships; he notes that many sailing ships filled their holds with the cargo of such inland watercraft as canal boats and James River batteaux. In the spring of 1771 Virginia suffered her greatest known natural disaster, "The Great Freshet of 1771." It rained on ten consecutive days, at times torrentially, and parts of the James River basin were swept by 25 feet ofwater. 1 Nearly all of the boats the tobacco planters depended upon for hauling their goods to Richmond were swept away. At that time, the most widely used boat type for this trade was actu- ally a combination oftwo boats, called the Rose tobacco canoe.Two large dugout canoes, 50 to 60 feet long, were fitted with cross-beams, using lashings and pins, thus making a twin-hulled craft that could carry up to ten hogsheads of tobacco. After delivery, the canoes could be separated for the return upstream. Three to five men could handle the down-river trip, and two men to a canoe could handily pole and/or paddle a canoe on the return. This scheme was introduced sometime between 1748 and 1750 by two tobacco planters in Albemarle County, the Rev. -

New River Wild & Scenic River Study West Virginia and Virginia

New River Wild & Scenic River Study West Virginia and Virginia Study Report 2009 Prepared By: U.S. Department of Interior National Park Service Northeast Regional Office Philadelphia Participating Agencies: National Park Service: New River Gorge National River Northeast Regional Office Washington Office U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Bluestone Dam Huntington District Office Virginia Secretariat of Natural Resources: Department of Game and Inland Fisheries Department of Conservation and Recreation West Virginia Division of Natural Resources: Parks and Recreation Section Wildlife Resources Section Acronyms and Abbreviations ACE U.S. Army Corps of Engineers APCO Appalachian Power Company (subsidiary of the American Electric Power Company) BMP Best management practices (management practices generally recognized to be effective and practicable in minimizing the impacts of land management activities such as agriculture and forestry) CFS Cubic feet per second (measurement of river flow) DCR Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation DGIF Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries DNR West Virginia Division of Natural Resources (includes the Wildlife Resources Section and the Parks and Recreation Section) DNR-Parks The Parks and Recreation Section within the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources DNR-WRS The Wildlife Resources Section within the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources DOI United States Department of the Interior EA Environmental Assessment (report required by the National Environmental Policy Act) FERC Federal Energy Regulatory Commission NEPA National Environmental Policy Act NERI New River Gorge National River (internal National Park Service acronym used for administrative purposes) NERO Northeast Regional Office of the National Park Service, headquartered in Philadelphia, PA NPS U.S. National Park Service NRA National Recreation Area (examples: Gauley River NRA, Mt. -

Essex Historical Society Papers and Addresses Volume 3 Essex Historical Society

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor SWODA: Windsor & Region Publications Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive 1921 Essex Historical Society Papers And Addresses Volume 3 Essex Historical Society Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/swoda-windsor-region Part of the Canadian History Commons Recommended Citation Essex Historical Society, "Essex Historical Society Papers And Addresses Volume 3" (1921). SWODA: Windsor & Region Publications. 64. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/swoda-windsor-region/64 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Southwestern Ontario Digital Archive at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in SWODA: Windsor & Region Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. :-·r-.-· .. •. ·. -:- I - . ~ ···:~.. ->'·-.:~ ..... _ . ....... ' ' .., .... - . ·-=~- Essex Historical Socie~y . ..- . /·" ' . .. ; .. ,_.., PAPERS ·-. ' ' ADDRESSES I . • VOLUME ill. -; •. ... .. ~ :... -I -~ -"... -1 ' -, , . .. ·• :.,:,. ECHO PBINT. .,, -~;_:.r Windsor Public Lib!~ <<":.{ . ·. \ ·:;:·, . .. ·, . : --~-~~-.; • 't ; • f • > • • • -I • -I • • / " • ~. ~ ., ' - .. '.. ~- '· ,/.-I Essex Historical Society. Organized 5th January, 1904. :~ Officers, 1921. Honorary President Francis Cleary President A. Phi. E. Panet Vice-President Fred. Neal Secretary-Treasurer Andrew Braid · Executive Committee: Officers as above, and Judge George Smith and Messrs. George F. Macdonald, Alex. Gow and Fred. J. Holton. " ? ---~· ..'· . \ ' I . •. ' • • 0 • • • / i I I • J I I l Ii i HISTORY OF THE WINDSOR AND DETROIT FERRIES I . (Read at a meeting of the Essex Historical Society December 14th, 1916.) • By F. J. Holton, D. H. Bedford and Francis Cleary. J f •t In the early days of the eighteenth century in th~ I Great Lakes region, transportation was to a great extent t 'i carried on by means of birch bark canoes and bateaux. -

Pre-Steamboat Navigation on the Lower Mississippi River. John Amos Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1963 Pre-Steamboat Navigation on the Lower Mississippi River. John Amos Johnson Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Johnson, John Amos, "Pre-Steamboat Navigation on the Lower Mississippi River." (1963). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 892. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/892 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 64—5052 microfilmed exactly as received JOHNSON, John Amos, 1929- PRE-STEAMBOAT NAVIGATION ON THE LOWER MISSISSIPPI RIVER. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1963 G eography University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan PRE-STEAMBOAT NAVIGATION ON THE LOWER MISSISSIPPI RIVER A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by John Amos Johnson B.S., Memphis State University, 1951 M.A., The University of Tennessee, 1953 August, 1963 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Grateful and sincere gratitude is acknowledged to Professor Pred B. Kniffen who directed this dissertation. Helpful advice was given by the critical readers Professors William G. Haag, James P. Morgan, John H. Vann, and Harley J. Walker. Knowledge gained in courses from Professors Robert C. -

The Chesapeake Log Canoe

“The manner of making their boats,” a circa-1590 Theodor de Bry colored engraving after a John White painting, shows how Powhatan Indians hollowed a log by burning, then scraping out coals and ash. Indians used fire to fell and hollow out their dugouts by slowly burning the wood and scraping out the coals and ash. Imported metal hand tools reduced the time necessary to build a canoe. The use of the hand adz, a European metal Economics Shape tool, streamlined canoe Log canoes on the James River in 1906. the Canoe construction. The story of the Chesapeake Bay log Increasing world demand for Pocomoke and Tilghmans Island log canoes of canoe is a reflection of the environment of the bay, the Chesapeake’s bounty of tobacco, fish and oysters Maryland’s Eastern Shore – shared a common form the needs of the communities served, and evolutionary led to a need for larger workboats. The development but differed in important hull details and rigging. changes to the construction and shape of the vessel. of the tobacco canoe and multi-log hulls allowed for For more than three centuries, the log canoe was larger cargoes to be transported more efficiently. The Bateaus, Brogans & Bugeyes essential to life on the Chesapeake Bay, the United tobacco canoe was created by lashing two hulls together Other Chesapeake Bay workboats grew out of the States’ largest estuary, for travel, harvest and trade. The by crossbeams, providing a catamaran with a steady log canoe tradition. A punt was a simple craft for log canoe evolved and thrived on the bay until it was platform to carry multiple hogshead casks of tobacco.