The Smithfield Review, Volume VI, 2002, Crawford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blue Ridge Park Way DIRECTORY TRAVEL PLANNER

65 TH Edition Blue Ridge Park way www.blueridgeparkway.org DIRECTORY TRAVEL PLANNER Includes THE PARKWAY MILEPOST Biltmore Asheville, NC Exit at Milepost 388.8 Grandfather Mountain Linville, NC Exit at Milepost 305.1 Roanoke Star and Overlook Roanoke, VA Exit at Milepost 120 Official Publication of the Blue Ridge Parkway Association The 65th Edition OFFICIAL PUBLICATION BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY ASSOCIATION, INC. P. O. BOX 2136, ASHEVILLE, NC 28802 (828) 670-1924 www.blueridgeparkway.org • [email protected] COPYRIGHT 2014 NO Portion OF THIS GUIDE OR ITS MAPS may BE REPRINTED WITHOUT PERMISSION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN THE USA. Some Parkway photographs by William A. Bake, Mike Booher, Vicki Dameron and Jeff Greenberg © Blue Ridge Parkway Association Layout/Design: Imagewerks Productions: Arden, NC This free Directory & Travel PROMOTING Planner is published by the 500+ member Blue Ridge TOURISM FOR Parkway Association to help Chimney Rock at you more fully enjoy your Chimney Rock State Park Parkway area vacation. MORE THAN Members representing attractions, outdoor recre- ation, accommodations, res- Follow us for more Blue Ridge Parkway 60 YEARS taurants, shops, and a variety of other services essential to information and resources: the traveler are included in this publication. When you visit their place of business, please let them know www.blueridgeparkway.org you found them in the Blue Ridge Parkway Directory & Travel Planner. This will help us ensure the availability of another Directory & Travel Planner for your next visit -

County of Roanoke Finance Department Purchasing Division

COUNTY OF ROANOKE FINANCE DEPARTMENT PURCHASING DIVISION Kate Hoyt Buyer P.O. Box 29800 5204 Bernard Drive SW, Suite 300F Roanoke, VA 24018 Phone: (540) 283-8149 [email protected] November 9, 2018 REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS #2019-058 Food, Beverage, Programming, RV Camping, and Retail Services at Roanoke County’s Explore Park Sealed Proposals Due: January 9, 2019 2:00 PM (Local Prevailing Time) One (1) unbound original Five (5) bound complete copies One (1) electronic copy (USB preferred) RFP #2019-058 FOOD, BEVERAGE, PROGRAMMING, RV CAMPING, & RETAIL SERVICES AT EXPLORE PARK GENERAL INFORMATION Roanoke County is seeking proposals from qualified firms to provide a plan for the development and management, use, and operation of food, beverage, gas, programming , RV camping, and retail services at Explore Park in Roanoke, Virginia. A non-mandatory Pre-Proposal meeting will be held at 3:00 pm on November 28, 2018, at the Arthur Taubman Center located at 56 Roanoke River Parkway Rd, Blue Ridge Parkway Milepost 115, Roanoke, VA 24014. It is recommended that those intending to submit a proposal attend this meeting. Parks, Recreation and Tourism staff will make a brief presentation and be available for questions. One unbound original, five (5) bound complete copies and one electronic copy (USB preferred) of the proposals, in a sealed envelope/package, will be received at and until January 9, 2019, at 2:00 PM (local prevailing time), in the Roanoke County Purchasing Division at 5204 Bernard Drive, Suite 300F, Roanoke, Virginia 24018. NO faxed proposals will be accepted. It is the responsibility of the Offeror to ensure that its proposal is received in the Purchasing Division by the above date and time. -

Blue Ridge Parkway Long-Range Interpretive Plan Was Approved by Your Memorandum, Undated

6o/%. .G3/ . B LU E R IDG E PAR KWAY r . v BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE . ;HNICAL INFOR1uA1-!ON CENTER `VFR SERVICE CENTER Z*'K PARK SERVICE 2^/ C^QZ003 United States Department of the Interior NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Harpers Ferry Center P.O. Box 50 IN REPLY REFER TO: Harpers Ferry, West Virginia 25425-0050 K1817(HFC-IP) BLRI 'JAN 3 0 2003 Memorandum To: Superintendent, Blue Ridge Parkway From: Associate Manager, Interpretive Planning, Harpers Ferry Center Subject: Distribution of Approved Long-Range Interpretive Plan for Blue Ridge Parkway The Blue Ridge Parkway Long-Range Interpretive Plan was approved by your memorandum, undated. All changes noted in the memorandum have been incorporated in this final document. Twenty bound copies are being sent to you with this memorandum, along with one unbound copy for your use in making additional copies as needed in the future. We have certainly appreciated the fine cooperation and help of your staff on this project. Enclosure (21) Copy to: Patty Lockamy, Chief of Interpretation bcc: HFC-Files HFC-Dailies HFC - Keith Morgan (5) HFC - Sam Vaughn HFC - Dixie Shackelford Corky Mayo, WASO HFC - John Demer HFC- Ben Miller HFC - Anne Tubiolo HFC-Library DSC-Technical Information Center K.Morgan/lmt/1-29-03 0 • LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY 2002 prepared by Department of the Interior National Park Service Blue Ridge Parkway Branch of Interpretation Harpers Ferry Center Interpretive Planning 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS M INTRODUCTION ..........................................1 BACKGROUND FOR PLANNING ...........................3 PARKWAY PURPOSE .......................................4 RESOURCE SIGNIFICANCE ................................5 THEMES ..................................................9 0 MISSION GOALS ......................................... -

A Herpetological Survey of Dixie Caverns and Explore Park in Roanoke, Virginia and the Wehrle’S Salamander

A Herpetological Survey of Dixie Caverns and Explore Park in Roanoke, Virginia and the Wehrle’s Salamander Matthew Neff Department of Herpetology National Zoological Park Smithsonian Institution MRC 5507, Washington, DC 20013 Introduction The Virginia Herpetological Society (VHS) Dixie Caverns Survey was held at Dixie Caverns and Explore Park in Roanoke County, Virginia on 24 September 2016. According to legend, Dixie Caverns was discovered in 1920 by two young men after their dog Dixie fell through a hole that led to the caves. In honor of their dog’s discovery, they decided to name the caverns Dixie. One of those boys was Bill “Shorty” McDaniel who would later go on to work at the caverns for more than 50 years and was known fondly for his sometimes embellished stories (Berrier, 2014). In actuality, the presence of Dixie Caverns, according to The Roanoke Times, was known as early as 1860 and had been mapped in the early 1900’s (Berrier, 2014). Guided tours of the caverns began in 1923 and still occur today with about 30,000 people visiting annually (Berrier, 2014). Dixie Caverns is located in Roanoke County which is in the Valley and Ridge and Blue Ridge provinces (Mitchell, 1999). A key feature of the Valley and Ridge is karst topography with soluble rocks such as limestone which create caves and caverns when weathered (Tobey, 1985). Over millions of years the caverns were formed as water dissolved the limestone that created Catesbeiana 38(1):20-36 20 Dixie Caverns and Explore Park Survey holes and even larger passageways. Many of the rock formations in Dixie Caverns are made of calcite which was formed by dripping water that evaporated leaving behind tiny particles which eventually created stalactites (Berrier, 2014). -

Narrative of Richard Jones, Excerpts: a Boatman on the Broad River, 9

National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 Narrative of Library of Congress Richard Jones EXCERPTS: A BOATMAN ON THE BROAD RIVER *Enslaved in South Carolina, ca. 1830s(?)-18651 Interview conducted 9 July 1937 Union, South Carolina Federal Writers’ Project, WPA In the 1930s over 2,300 formerly enslaved African Americans were interviewed by members of the Federal Writers' Project, a New Deal agency in the Works Progress Administration (WPA) during the Great Depression. Richard Jones was a slave on a large South Carolina cotton plantation owned by Jim Gist (killed in battle during the Civil War). Around 100 years old when interviewed, Jones describes African American boatmen on a river bateau, his work as a boatman transporting Gist’s cotton from northern West Virginia, 1872 South Carolina down the Broad River to Columbia in the middle of the state, there to be shipped to Charleston and beyond for sale. The interview excerpts are presented as transcribed by the interviewer (parenthetical comments in original transcript; bracketed notes added by NHC). Mr., I run on Broad River fer over 24 years as boatman, carrying Marse [Master] Jim’s cotton to Columbia fer him. Us had de excitement on dem trips. Lots times water was deeper dan a tree is high. Sometimes I was throwed and fell in de water. I rise up every time, though, and float and swim back to de boat and git on again. If de weather be hot, I never think of changing no clothes, but just keep on what I got wet. -

Vision 2040: Amendments and Administrative Modifications

Vision 2040: Amendments and Administrative Modifications The Constrained Long-Range Multimodal Transportation Plan, Vision 2040: Roanoke Valley Transportation, was approved by the Roanoke Valley Transportation Planning Organization Policy Board on September 27, 2017. As such, from time to time, amendments and administrative modifications are necessary in order to reflect changes in projects, funding, or programs. For purposes of this section, and as defined in 23 Code of Federal Regulations §450.104, amendments and administrative modifications are to mean the following: Administrative modification means a minor revision to a long-range statewide or metropolitan transportation plan, Transportation Improvement Program (TIP), or Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) that includes minor changes to project/project phase costs, minor changes to funding sources of previously included projects, and minor changes to project/project phase initiation dates. An administrative modification is a revision that does not require public review and comment, a re-demonstration of fiscal constraint, or a conformity determination (in nonattainment and maintenance areas). Amendment means a revision to a long-range statewide or metropolitan transportation plan, TIP, or STIP that involves a major change to a project included in a metropolitan transportation plan, TIP, or STIP, including the addition or deletion of a project or a major change in project cost, project/project phase initiation dates, or a major change in design concept or design scope (e.g., changing project termini or the number of through traffic lanes or changing the number of stations in the case of fixed guideway transit projects). Changes to projects that are included only for illustrative purposes do not require an amendment. -

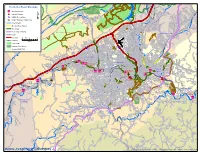

Roanoke River Blueway Access Points

h F !F ! KINZIE 4TH OAK Roanoke River BluewayMILLER RAMP HUMBERT CRAIGVALLEY WALNUT POPLAR GILLIE FIELDS KEFFER CATAWBA CREEK OLDE RT 604 SKY OLD TRAM MOUNTAIN !F MAPLE !| Blueway Access !F OAKWOOD BLUE RIDGE OAK COALING PARKVIEW BUGLE INTERSTATESIMMONS 81 FLINT SPRING HOLLOW ` 648 DOVE _ Æ SCALYBARK Hazard/Portage GIBSON RIDGE DEREK APACHE ÿ CASEY WATES CALDER RIDGE CARVINS COVE DOGAN LULA SUMMIT h TIMER PINE USGS Stream Gage RESERVOIR LAKEVIEW STONEBRIDGE MOUNTAIN PASS BRADSHAW BRYANT JENSEN N & W 2ND LACEY KIDDER LONGWOOD ¹ ALLTREE CATAWBA VALLEY!F WINDFALL !F VDGIF Birding & Wildlife Site UPDIKE MORNING DOVE INTERSTATE 81 HUNTERS FOXCROFT BLUEBIRD CLOVERDALE LEE COUGAR LAYMANTOWN BENDING OAK CHASE KEATON ANGEL DAN LAKERIDGE C FACULTY VISTA River/Stream MOORE AUTUMN GANDER a COOK DEER FAIRFIELD LOMAN r ENON v INDUSTRIAL COLONIAL in BRITISH WOODS I81 TOAD CLOVERDALE Carvins Cove BELLE HAVEN s RICHARDSON Stocked Trout Waters !F LILA MCINTOSH C HOPE FILLY APPLE Natural Reserve LABAN r STAYMAN e WILLIAMSON SHADWELL ARCHWAY SOFT e YORK TIMBERVIEW CALVERT HITECH k CAROLINA POST OAK GreenwayARABIAN BARRENS INDIAN TERESA KNOLLWOOD ALPINE PARK HUNTERS WEBSTER NEWPORT OLSEN WILLIAMSONDEXTER HUGH ROYCE Blue Ridge Parkway Loch Haven WEST Havens Wildlife Management Area JANEE VIVIAN EAST SERENITY BOXLEY HOLLINS WOOD HAVEN Botetourt County CRESTLAND QUAIL DOE RAY Road I81 BUCK MANOR SANDYRIDGE DUTCH OVEN HEDGELAWN OAKLANDELDEN THIRLANE OLD MOUNTAIN NELL DENT ROME LOCH HAVEN SHORE AIRPORT TINY CAPITO FLORIST SIERRA Interstate 00.5 1 2 RAM DAVIS BLACKSBURG -

Virginia Mountains

VIRGINIA MOUNTAINS LAKE MOOMAW Warm Springs PET-FRIENDLY LOVEWORK It’s your turn to sniff out You’ll have no treasures, while your trouble entertaining dog tags along! Wander yourself at Smith the 40,000-square-foot Mountain Lake, and warehouse and two outside the new LOVEwork acres at Black Dog Salvage, provides even packed with amazing more inspiration. creative architectural and The L-O-V-E letters VIRGINIA repurposed products. Shop paint a picture of for furniture and home the 20,600-acre décor, outdoor gems, Black lake, 500 miles of Dog furniture paint and shoreline and iconic MOUNTAINS oh-so-much-more. And you highpoints. The sign, and your companion just BLUE RIDGE PARKWAY by local artist Lisa might meet resident black Bedford Floyd, captures the dogs Molly May and Stella beauty of the lake – or the treasure hunters BUCKET LIST and surrounding of the DIY Network show Undoubtedly, the Blue Ridge Parkway serves up gorgeous views along mountains, “Salvage Dawgs.” hundreds of miles of mountain driving. Scenic overlooks make it easy to pull farmland, homes, over, absorb the beauty and refresh your soul. But there’s more! This ribbon shops, restaurants of road passes by iconic stops that showcase rich regional traditions and also and more – and all grants glimpses of abundant biodiversity and geological wonders. Take a hike, the different ways snap a pic or just soak in the wonders of nature. to enjoy its beauty. You’ll #LOVEVASML! ICONIC CARVINS COVE KAYAKING The natural beauty of the Peaks of Otter has Roanoke attracted visitors for centuries, from Native Americans to European settlers and Blue Ridge ASK A LOCAL Parkway travelers. -

Roanoke Valley- Alleghany

REGION 5 Roanoke Valley- Alleghany North Mountain, Alleghany Highlands | Chuck Almarez CHAPTER 13 Regional Recommendations Region 5 • Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Dragon’s Tooth on the Appalachian Trail | Sam Dean/Virginia Tourism Corp. Introduction Table 5.2 Top 10 Outdoor Recreation Activities By Participation The Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Recreational Planning Region includes the counties of Alleghany, Botetourt, Craig and Roanoke, Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Recreational Planning Region the cities of Covington, Roanoke and Salem, and the towns of Clifton Forge, Iron Gate, Fincastle, Troutville, Buchanan, New % activity Castle and Vinton. Stretching from the Blue Ridge Mountains household across the Shenandoah Valley to the ridge and valley section of the Appalachian Mountains, the region is a mixture of urban Driving for pleasure 73 centers and rural farms and forests. Marked by topographic variety, Visiting natural areas 71 numerous rivers, streams, and many notable cultural and historic sites, the area offers a range of historic and outdoor experiences. Walking for pleasure 67 Whether hiking the Appalachian Trail or driving the Blue Ridge Parkway, exploring the George Washington and Jefferson National Visiting parks (local, state & national) 49 Forests or paddling the James River, the outdoor enthusiast’s choices of activities are many. Sunbathing/relaxing on a beach 48 Outdoor festivals (music festivals, Regional Focus outdoor-themed festivals, extreme sports 47 festivals, etc.) Table 5.1 Most-Needed Outdoor Recreation Opportunities Swimming/outdoor pool 46 Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Recreational Planning Region Viewing the water 36 % of households in Swimming/beach/lake river (open water) 35 activity region state Music festivals 34 Natural areas 58 54 Source: 2017 Virginia Outdoors Demand Survey. -

State Route 116 Corridor Review.Indd

STATE ROUTE 116 CORRIDOR REVIEW -ROANOKE COUNTY AND THE CITY OF ROANOKE- Roanoke Valley Area Metropolitan Planning Organization July 2008 Acknowledgements ROANOKE VALLEY AREA METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION (MPO) POLICY BOARD David Trinkle, Chair Billy Martin, Sr. Richard Flora, Vice Chair Joe McNamara Doug Adams Alvin Nash Richard Caywood J. Lee E. Osborne Tony Cho Melinda Payne Tammy Davis Jackie Shuck Darrell Feasel Ron Smith Carolyn Fidler Dave Wheeler William E. Holdren, Jr. PROJECT TEAM Matthew Rehnborg Jake Gilmer This report was prepared by the Roanoke Valley Area Metropolitan Planning Or- ganization (RVAMPO) in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), and the Virginia Depart- ment of Transportation (VDOT). The contents of this report refl ect the views of the staff of the Roanoke Valley Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO). The MPO staff is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The con- tents do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial views or policies of the FHWA, VDOT, or RVARC. This report does not constitute a standard, specifi cation, or regulation. FHWA or VDOT acceptance of this report as evidence of fulfi llment of the objectives of this planning study does not constitute endorsement/approval of the need for any recommended improvements nor does it constitute approval of their location and design or a commitment to fund any such improvements. Additional project level environmental impact assessments and/or studies of alternatives -

View a Low Resolution Pdf File Click Here

AMAZING VIRGINIA CANALS A VIRGINIA CANALS AND NAVIGATIONS SOCIETY RIVER ATLAS PROJECT ORIGINAL PAINTINGS OF VIRGINIA’S MOST FAMOUS CANAL SCENES By artists Art Markel, Bill Hoffman and others. Photographs by Philip de Vos and Holt Messerly, with text by William E. Trout, III. FOR THE VIRGINIA CANALS & NAVIGATIONS SOCIETY “Thus all works pass directly out of the hands of the architect into the hands of nature, to be perfected.” Henry David Thoreau, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, 1849. DEDICATED TO NANCY ROBERTS DUNNAVANT TROUT, 1929 - 2012 PROCEEDS FROM THE SALE OF THIS PUBLICATION SUPPORT CANAL AND RIVER PROJECTS OF THE VIRGINIA CANALS & NAVIGATIONS SOCIETY, THE NON-PROFIT VOLUNTEER ORGANIZATION DEDICATED TO HISTORIC CANAL AND RIVER NAVIGATION RESEARCH, PRESERVATION, RESTORATION AND PARKS. COPIES OF THE SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS ARE AVAILABLE ON WWW.VACANALS.ORG/SHOP, AND FROM RICHARD A. DAVIS, VC&NS SALES, 4066 TURNPIKE ROAD, LEXINGTON, VA 24450. THE SOCIETY’S VIRGINIA CANAL MUSEUM IS IN AMHERST COUNTY THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE JAMES RIVER BATTEAU, AT 3806 SOUTH AMHERST HIGHWAY, MADISON HEIGHTS, VIRGINIA 24572. 5.1 MILES NORTH OF LYNCHBURG ON BUSINESS ROUTE 29. Above: Watercolor by Art Markel of George Washington passing through Richmond’s Lower Arch in December 1791 during his triumphal tour of the United States, after retiring from the Presidency. For this special occasion, his batteau crew was dressed up in “red coaties.” His batteau was poled up the Lower Canal from (almost) downtown Richmond, through this arch, which protected the canal from river floods. The batteau continued up the James and through the Upper Canal, with its two stone locks, at Old Westham. -

A Publication of the Virginia Canals and Navigations Society Summer 2007 Volume 28, Issue 2 2

The Tiller A Publication of the Virginia Canals and Navigations Society Summer 2007 Volume 28, Issue 2 2 2 The Tiller President Watercraft Operations Dan River Robert M. “Buddy” High William E. Turnage Bob Carter General Delivery 6301 Old Wrexham Pl. 1141 Irvin Farm Rd. Valentine, VA 23887 Chesterfield, VA 23832 Reedsville, NC 27320 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] (434) 577-2427 Board of Trustees Eastern Virginia Vice-President Natalie Ross Kyle Schilling vacant PO Box 8224 30 Brook Crest Ln. Charlottesville, VA 22906 Stafford, VA 22554 Recording Secretary [email protected] (434) 577-2427 Jean High Term: 2007-2012 General Delivery Northern Virginia Valentine, VA 23887 Douglas MacLeod Myles “Mike” R. Howlett [email protected] PO Box 3119 6826 Rosemont Dr. Lynchburg, VA 24503 McLean, VA 22101 Corresponding Secretary [email protected] [email protected] Lynn Howlett Term: 2006-2011 6826 Rosemont Dr. Richmond William E. Trout, III, Ph.D. McLean, VA 22101 Vacant [email protected] 35 Towana Rd. Richmond, VA 23226 [email protected] Rivanna River Treasurer Term: 2005-2010 Peter C. Runge Atwill R. Melton 119 Harvest Dr. 1587 Larkin Mountain Rd. William E. Turnage Charlottesville, VA 22903 Amherst, VA 24521 See Watercraft Operations [email protected] [email protected] Term: 2004-2009 Southeast Virginia Archivist/Historian Richard Davis George Ramsey Phillip Eckman See VCNS Sales 2827 Windjammer Rd. 902 Park Ave. Term: 2003-2008 Colonial Heights, VA 23834 Suffolk, VA 23435 [email protected] [email protected] Webmaster District Directors Staunton River George Ramsey, Jr. Roy Barnard [email protected] Appomattox River 94 Batteau Rd.