TORONTO BY-LAWS No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presépio Vivo No Lusitania Do Toronto

PÂG. 5 PâG. 26 J y-HCO t.MiUiTD S/J>lTO TORONTO RCPRESENTATIVE OFFICE 860-c COLLEGE STREET WEST loào lardim gostava MAISFOBTES TORONTO, ON M6H 1A2 de 'lazer uma coisa" 804 Dupont St. at Shaw - TOROHTO Lord of the Rings TEL.416-530-1700 FAX: 416-530-0067 1-800-794-8176 E-MAIL: [email protected] . 4 <16-531-5401 Um filme a nao perder na Europa WWW.BES.PT CIIOJ CANADIAN PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #1414526 O MILENIO PORTUGUESE-CANADIAN NEWSPAPER • THURSDAY 27th December, 2001 • ANO III EDIÇÂO N° 163 • PREÇO: 50C™CL GST Presépio vivo no (D)eficientes em concorrida lusitania do Toronto testa de Natal CONTINUA NA PAGINA 13 CiRV frnm oMaENioj DESEJAM A TODOS BOAS FESTAS TV newspaper Nonas pon dia ria sua oonnpariNia 2 Quinta-feira, 27 Dezembro, 2001 COMUNIDADE O MILéNIO sem vértebras O ultimo jogo entre o BENFICA e o SPORTING, pagar. no Estadio da Luz, ficou para a historia por varias Mas, dinheiro para a compra de muitos jogadores, razôes. hâ sempre!?... Para além das peripécias do prôprio jogo, com Ainda hoje nâo compreendo como é que muitas acusaçôes a recairem sobre o arbitre da conseguiram chegar a um consenso correcte e legal partida, aquele jogo foi o de despedida dos velhos entre os CLUBES e as SAD's. rivais no estâdio, e foi o domingo que marcou o Na SAD-Benfica, hâ muito dinheiro. No S.L. e começo do fim do Estâdio dâ Luz. Benfica, nâo hâ um chavo (e isto é igual, na minha Foi também a estreia do "derby" no circuito da opiniâo, para corn os outres clubes e suas SAD's). -

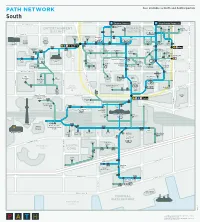

PATH Underground Walkway

PATH Marker Signs ranging from Index T V free-standing outdoor A I The Fairmont Royal York Hotel VIA Rail Canada H-19 pylons to door decals Adelaide Place G-12 InterContinental Toronto Centre H-18 Victory Building (80 Richmond 1 Adelaide East N-12 Hotel D-19 The Hudson’s Bay Company L-10 St. West) I-10 identify entrances 11 Adelaide West L-12 The Lanes I-11 W to the walkway. 105 Adelaide West I-13 K The Ritz-Carlton Hotel C-16 WaterPark Place J-22 130 Adelaide West H-12 1 King West M-15 Thomson Building J-10 95 Wellington West H-16 Air Canada Centre J-20 4 King West M-14 Toronto Coach Terminal J-5 100 Wellington West (Canadian In many elevators there is Allen Lambert Galleria 11 King West M-15 Toronto-Dominion Bank Pavilion Pacific Tower) H-16 a small PATH logo (Brookfield Place) L-17 130 King West H-14 J-14 200 Wellington West C-16 Atrium on Bay L-5 145 King West F-14 Toronto-Dominion Bank Tower mounted beside the Aura M-2 200 King West E-14 I-16 Y button for the floor 225 King West C-14 Toronto-Dominion Centre J-15 Yonge-Dundas Square N-6 B King Subway Station N-14 TD Canada Trust Tower K-18 Yonge Richmond Centre N-10 leading to the walkway. Bank of Nova Scotia K-13 TD North Tower I-14 100 Yonge M-13 Bay Adelaide Centre K-12 L TD South Tower I-16 104 Yonge M-13 Bay East Teamway K-19 25 Lower Simcoe E-20 TD West Tower (100 Wellington 110 Yonge M-12 Next Destination 10-20 Bay J-22 West) H-16 444 Yonge M-2 PATH directional signs tell 220 Bay J-16 M 25 York H-19 390 Bay (Munich Re Centre) Maple Leaf Square H-20 U 150 York G-12 you which building you’re You are in: J-10 MetroCentre B-14 Union Station J-18 York Centre (16 York St.) G-20 in and the next building Hudson’s Bay Company 777 Bay K-1 Metro Hall B-15 Union Subway Station J-18 York East Teamway H-19 Bay Wellington Tower K-16 Metro Toronto Convention Centre you’ll be entering. -

Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register and Intention to Designate Under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act - 100 College Street

REPORT FOR ACTION Inclusion on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register and Intention to Designate under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act - 100 College Street Date: August 7, 2020 To: Toronto Preservation Board Toronto and East York Community Council From: Senior Manager, Heritage Planning, Urban Design, City Planning Wards: Ward 11 - University-Rosedale SUMMARY This report recommends that City Council state its intention to designate the property at 100 College Street under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act and include the property on the City of Toronto's Heritage Register. The Banting Institute at 100 College Street, is located on the north side of College Street in Toronto's Discovery District, on the southern edge of the Queen's Park/University of Toronto precinct, opposite the MaRS complex and the former Toronto General Hospital. Following the Nobel-Prize winning discovery of insulin as a life- saving treatment for diabetes in 1921-1922, the Banting Institute was commissioned by the University of Toronto to accommodate the provincially-funded Banting and Best Chair of Medical Research. Named for Major Sir Charles Banting, the five-and-a-half storey, Georgian Revival style building was constructed according to the designs of the renowned architectural firm of Darling of Pearson in 1928-1930. The importance of the historic discovery was recently reiterated in UNESCO's 2013 inscription of the discovery of insulin on its 'Memory of the World Register' as "one of the most significant medical discoveries of the twentieth century and … of incalculable value to the world community."1 Following research and evaluation, it has been determined that the property meets Ontario Regulation 9/06, which sets out the criteria prescribed for municipal designation under Part IV, Section 29 of the Ontario Heritage Act, for its design/physical, historical/associative and contextual value. -

Court File No. CV-15-10832-00CL ONTARIO

Court File No. CV-15-10832-00CLCV-l5-10832-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OFOF' JUSTICE [COMMERCIALICOMMERCTAL LIST]LrSTI IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES' CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c.C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OFOF A PLANPLAN OFOF'COMPROMISE COMPROMISE AND ARRANGEMENT OFOF' TARGET CANADA CO., TARGET CANADACANADA HEALTH CO., TARGET CANADA MOBILE GP CO., TARGET CANADACANADA PHARMACYPHARMACY (BC)(BC) CORP.,CORP., TARGETTARGET CANADACANADA PHARMACY (ONTARIO) CORP.,CORP., TARGETTARGET CANADACANADA PHARMACY CORP.,CORP., TARGETTARGET CANADA PHARMACY (SK)(sK) CORP.,coRP., and TARGET CANADA PROPERTY LLCLLc Applicants RESPONDING MOTION RECORD OF FAUBOURGF'AUBOURG BOISBRIAND SHOPPING CENTRE HOLDINGS INC. (Motion to Accept Filing ofof aa Plan andand Authorize Creditors'Creditorso MeetingMeeting toto VoteVote onon thethe Plan) (Returnable(Returnable DecemberDecemb er 21, 2015)201 5) Date: December 8,8,2015 2015 DE GRANDPRÉ CHAIT LLP Lawyers 10001000 DeDe.La La Gauchetière Street West Suite 2900 Montréal (Québec) H3B 4W5 Telephone: 514514 878-431187 8-4311 Fax:Fax:514 514 878-4333878-4333 Stephen M. Raicek [email protected]@,dgclex.com Matthew Maloley mmalole)¡@declex.commmaroleyedgclex.com Lawyers for FaubourgFaubourg Boisbriand Boisbriand Shopping Shopping Centre Holdings Inc. TO: SERVICE LIST CCAA Proceedings ofof TargetTarget CanadaCanada Co.etCo.et al,al, CourtCourt File No. CV-15-10832-00CLCV-l5-10832-00CL Main Service List (as(as atatDecember7,2015) December 7, 2015) PARTY CONTACTcqNTACT • OSLER,osLER, HOSKIN & HARCOURT -

Path Network

PATH NETWORK Also available as North and Central posters South Sheraton Centre 3min Yonge-Dundas Square 10min ADELAIDE ST W ADELAIDE ST W Northbridge 100 – 110 VICTORIA ST Place Yonge 11 Dynamic ENTERTAINMENT FINANCIAL Adelaide Funds Tower DISTRICT DISTRICT Scotia Plaza West PEARL ST 200 King 150 King West West Exchange Tower First Canadian Place The Bank Princess Royal of Nova of Wales Alexandra Scotia TIFF Bell Theatre Theatre Royal Bank 4 King Lightbox Building West St Andrew KING ST W KING ST W King 225 King Commerce Commerce West 145 King 121 King TD North Court Court North West West Tower TD Bank West Collins Pavilion Barrow Place EMILY ST EMILY ST One King West Metro Toronto-Dominion Centre Roy Thomson YORK ST COLBORNE ST Metro Hall Centre Design Commerce Court Hall 55 Exchange SCOTTSCOTT STST University TD West Toronto-Dominion 200 Tower Bank Tower Accessible Wellington route through 222 Bay Commerce Level -1 West 70 York Court South WELLINGTON ST W WELLINGTON ST W Bay WELLINGTON ST E Wellington UNIVERSITY AVE Tower CBC North Brookfield The 95 Wellington SIMCOESIMCOE STST Broadcast RBC Tower BAY ST Place JOHN ST JOHN ST Centre Ritz-Carlton Centre West TD South Toronto Tower Royal Bank Plaza 160 Front Fairmont Royal York Street West TD Canada Hockey Hall FRONT ST E under construction Trust Tower South of Fame Simcoe Tower Place Metro Toronto FRONT ST W Meridian Convention Centre YONGE ST Hall North Citigroup Union Place InterContinental Toronto Centre Great Hotel Hall UP Express Visitor THE ESPLANADE SKYWALK Information Centre York -

Idqr 310Urnal Moyal Arr4ttrrtural 3Jnfititutr of Qianaba

IDQr 310urnal moyal Arr4ttrrtural 3Jnfititutr of QIanaba '([he ~o~ctl J\rti1it£dural ~n£ititllt£ of {!lanaoa '<IToxonto, QI"utaba I N 0 E X VOL U iVI E IV, 1927 Month and Page Month and Page Academy Exhibition, The, by F . H. Brigden, Pres. O.S.A ... Jan., p. 19 jubilee Coinage, Awards for Designs .. .......... Oct., p. 348 Activities of Provincial Associations- Alberta .... .. ... .. ... ..... ....... ... ..... .... .. ApI'. , p. 155 Live rpool Cath edral, by Philip J. Turner , F .R.I.B.A . Mar., p. 89 British Columbia . Jan., p. 39; Apr., p . 155 ; Nov., p. xxvi; Dec., p. 453 Manit~ba .... Jan., p. 39; Apr., p. 156; July, p. 270; Oct., p. 380 Manufacturers' Publications Received Aug , p . xxx; Sept., p. xxxvi Ontario .. jan., p. 39 ; Feb., p. 73; Apr., p. 156; May, p . 196 ; MantilTIe AssociatIon of Architects, Organization of . .. Oct., p. 376 june, p. 235; July, p. 270 ; Dec., p. 453 Masonic Peace MelTIorial, London, Eng. , Design for, by David R. Border C i ties Chapter. .. ... May, p. 197 Brown .. ........ ..... ....... ...... ..."""" .J an., p. 28 Hamilton Chapter . Ottawa Ch apter ..: : : F~b.; p. ii; M~Y , p. 197 Notes- jan., p. xxvi; Feb. , p. xxii ; Mar., xxii ; Ape , p. xviii ; May, Toronto Chapter . jan., p . 40 ; Feb., p. 73; May, p. 196; p. 198j June, p. xxvi; July, p . xxviii ; Aug., p. xxvi; Sept., p. xxxii ; june, p. 235 ; Oct. ,po 380; D ec. p. 454 Oct., p. 381; Nov., p. xxv iii j Dec., p. xxvi Quebec . .. .. .. .... Apr., p. 158 ; Sept., p. xxvi Saskatchewan . , Jan. , p. 40; Feb. , p . 74; Apr., p . -

SERVICE LIST BORDEN LADNER GERVAIS LLP Scotia Plaza, 40 King Street West Toronto, on M5H 3Y4 Edmond EB Lamek

1 SERVICE LIST BORDEN LADNER GERVAIS LLP GOODMANS LLP Scotia Plaza, 40 King Street West Bay Adelaide Centre Toronto, ON M5H 3Y4 333 Bay Street, Suite 3400 Toronto, ON M5H 2S7 Edmond E.B. Lamek Tel: 416-367-6311 Joe Latham Email: [email protected] Tel: 416-597-4211 Email: [email protected] Kyle B. Plunkett Tel: 416-367-6314 Jason Wadden Email: [email protected] Tel: 416.597.5165 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for Urbancorp CCAA Entities Lawyers for Reznik, Paz, Nevo Trustees Ltd., in its capacity as the Trustee for the Debenture Holders (Series A) and Adv. Gus Gissin, in his capacity as the Israeli Functionary of Urbancorp. Inc. THE FULLER LANDAU GROUP INC. GOLDMAN SLOAN NASH & HABER 151 Bloor Street West, 12th Floor (GSNH) LLP Toronto, ON M5S 1S4 480 University Avenue, Suite 1600 Toronto, ON M5G 1V2 Gary Abrahamson Tel: 416-645-6524 Mario Forte Fax: 416-645-6501 Tel: 416-597-6477 Email [email protected] Fax: 416-597-3370 Email: [email protected] Adam Erlich Tel: 416-645-6560 Robert J. Drake Fax: 416-645-6501 Tel: 416-597-5014 Email: [email protected] Fax: 416-597-3370 Email: [email protected] The Proposal Trustee Lawyers for the Proposal Trustee 2 BENNETT JONES LLP CHAITONS LLP 3400 One First Canadian Place 5000 Yonge Street, 10th Floor P.O. Box 130 Toronto, ON M2N 7E9 Toronto, ON M5X 1A4 Harvey Chaiton S. Richard Orzy Tel: 416-218-1129 Tel: 416-777-5737 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Lawyers for BMO Raj Sahni Tel: 416-863-1200 Email: [email protected] Jonathan G. -

EBRD Trade Facilitation Programme Confirming Banks

EBRD Trade Facilitation Programme Confirming Banks Table of Contents (Click on a country heading to go to that section) Algeria ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Angola...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Argentina ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Armenia ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Australia ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Austria ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Azerbaijan ................................................................................................................................................ 6 Bahrain .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Bangladesh .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Belarus.................................................................................................................................................... -

BLANEY MCMURTRY LLP Barristers & Solicitors 2 Queen Street East

Court File No. CV-19-00630241-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (COMMERCIAL LIST) IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES’ CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF NORTH AMERICAN FUR PRODUCERS INC., NAFA PROPERTIES INC., 3306319 NOVA SCOTIA LIMITED, NORTH AMERICAN FUR AUCTIONS INC., NAFA PROPERTIES (US) INC., NAFA PROPERTIES STOUGHTON LLC, NORTH AMERICAN FUR AUCTIONS (US) INC., NAFPRO LLC (WISCONSIN LLC), NAFA EUROPE CO-OPERATIEF UA, NAFA EUROPE B.V., DAIKOKU SP.Z OO and NAFA POLSKA SP. Z OO (the “Applicants”) SERVICE LIST TO: BLANEY MCMURTRY LLP Barristers & Solicitors 2 Queen Street East, Suite 1500 Toronto ON M5C 3G5 David T. Ullmann Tel: 416-596-4289 Fax: 416-594-2437 Email: [email protected] Stephen Gaudreau Tel: 416-596-4285 Email: [email protected] Natasha Rambaran Tel: 416- 593-3924 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for the Applicants 50695423.1 AND TO: MILLER THOMSON LLP Barristers and Solicitors 40 King Street West, Suite 5800 Toronto, Ontario M5H 3S1 Kyla Mahar Tel: 416-597-4303 Fax: 416-595-8695 Email: [email protected] Asim Iqbal Tel: 416-597-6008 Fax: 416-595-8695 Email: [email protected] Lawyers for the Monitor AND TO : DELOITTE RESTRUCTURING INC. Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower Suite 200, 22 Adelaide Street West Toronto, Ontario M5H 0A9 Phil Reynolds Tel: 416-956-9200 Fax: 416-601-6151 Email: [email protected] Todd Ambachtsheer Tel: 416-607-0781 Fax: 416-601-6151 Email: [email protected] Jorden Sleeth Tel: 416-775-8858 Fax: 416-601-6151 Email: [email protected] The Monitor 50695423.1 AND TO: THORNTON GROUT FINNIGAN LLP Barristers & Solicitors Suite 3200, 100 Wellington Street West Toronto, Ontario M5K 1K7 Leanne M. -

Trade Finance Program Confirming Banks List As of 31 December 2015

Trade Finance Program Confirming Banks List As of 31 December 2015 AFGHANISTAN Bank Alfalah Limited (Afghanistan Branch) 410 Chahri-e-Sadarat Shar-e-Nou, Kabul, Afghanistan National Bank of Pakistan (Jalalabad Branch) Bank Street Near Haji Qadeer House Nahya Awal, Jalalabad, Afghanistan National Bank of Pakistan (Kabul Branch) House No. 2, Street No. 10 Wazir Akbar Khan, Kabul, Afghanistan ALGERIA HSBC Bank Middle East Limited, Algeria 10 Eme Etage El-Mohammadia 16212, Alger, Algeria ANGOLA Banco Millennium Angola SA Rua Rainha Ginga 83, Luanda, Angola ARGENTINA Banco Patagonia S.A. Av. De Mayo 701 24th floor C1084AAC, Buenos Aires, Argentina Banco Rio de la Plata S.A. Bartolome Mitre 480-8th Floor C1306AAH, Buenos Aires, Argentina AUSTRALIA Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited Level 20, 100 Queen Street, Melbourne, VIC 3000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Adelaide Branch) Level 20, 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Adelaide Branch - Trade and Supply Chain) Level 20, 11 Waymouth Street, Adelaide, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Brisbane Branch) Level 18, 111 Eagle Street, Brisbane QLD 4000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Brisbane Branch - Trade and Supply Chain) Level 18, 111 Eagle Street, Brisbane QLD 4000, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Perth Branch) Level 6, 77 St Georges Terrace, Perth, Australia Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (Perth Branch -

56 Yonge Street, 21 Melinda Street, 18 to 30 Wellington Street West, 187 to 199 Bay Street and 25 King Street West - Zoning Amendment Application – Final Report

REPORT FOR ACTION 56 Yonge Street, 21 Melinda Street, 18 to 30 Wellington Street West, 187 to 199 Bay Street and 25 King Street West - Zoning Amendment Application – Final Report Date: June 18, 2019 To: Toronto and East York Community Council From: Director, Community Planning, Toronto and East York District Ward: 13 - Toronto Centre Planning Application Number: 17 277715 STE 28 OZ SUMMARY This application proposes to permit a 65-storey Class A office building and a 3-storey glass pavilion at the south end of the Commerce Court complex that will add 169,993 square metres of non-residential gross floor area, resulting in a total gross floor area of 361,560 square metres to the complex. The application also includes the retention of the heritage listed 8-storey Hotel Mossop building at 56 Yonge Street. The heritage designated Commerce Court complex will be altered to accommodate the new buildings, which includes the demolition of the existing 6-storey Commerce Court South building and the 13-storey Commerce Court East building. The façades of the east building will be reconstructed and incorporated into the new office building. The Commerce Court West and Commerce Court North buildings are being retained. The proposed development is consistent with the Provincial Policy Statement (2014) and conforms with the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (2019). This report reviews and recommends approval of the application to amend the Zoning By-laws. RECOMMENDATIONS The City Planning Division recommends that: 1. City Council amend Zoning By-law 438-86, for the lands at 56 Yonge Street, 21 Melinda Street, 18 to 30 Wellington Street West, 187 to 199 Bay Street and 25 King Street West substantially in accordance with the draft Zoning By-law Amendment attached as Attachment No. -

Notice of Motion Re Intercompany Claims Report Extension

Court File No.: CV-17-11846-00CL ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE COMMERCIAL LIST IN THE MATTER OF THE COMPANIES' CREDITORS ARRANGEMENT ACT, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-36, AS AMENDED AND IN THE MATTER OF A PLAN OF COMPROMISE OR ARRANGEMENT OF SEARS CANADA INC., CORBEIL ELECTRIQUE INC., S.L.H. TRANSPORT INC., THE CUT INC., SEARS CONTACT SERVICES INC., INITIUM LOGISTICS SERVICES INC., INITIUM COMMERCE LABS INC., INITIUM TRADING AND SOURCING CORP., SEARS FLOOR COVERING CENTRES INC., 173470 CANADA INC., 2497089 ONTARIO INC., 6988741 CANADA INC., 10011711 CANADA INC., 1592580 ONTARIO LIMITED, 955041 ALBERTA LTD., 4201531 CANADA INC., 168886 CANADA INC., AND 3339611 CANADA INC. Applicants NOTICE OF MOTION (returnable March 2, 2018) FTI Consulting Canada Inc., in its capacity as Court-appointed monitor (the "Monitor") in the proceedings of the Applicants pursuant to the Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. c-36, as amended (the "CCAA") will make a motion to a Judge, on Friday, March 2, 2018, at 9:00 am or as soon after that time as the motion can be heard, at the courthouse located at 330 University Avenue. PROPOSED METHOD OF HEARING: The motion is to be heard orally. THE MOTION IS FOR: 1 an Order, substantially in the form attached as Schedule "A" hereto (the "Intercompany Claims Report Extension Order"): (a) abridging the time for service of this Notice of Motion and the Motion Record, to be filed, and dispensing with service on any person other than those served; and CAN_DMS: \110801075\5 (b) extending the deadline by which the Intercompany Claims Report (as defined below) must be served on the Service List and filed with the Court to April 2, 2018; and 2 Such further and other relief as this Court may deem just.