LESSONS LEARNED Creating Successful Community-University Partnerships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2017 Download a PDF Version Of

FALL 2017 TACKLING THE IN CRISIS, HOPE AT THEIR SERVICE CDPE Aims to Positively UB Law Students BIG ISSUES Impact Drug Addiction Advocate for Veterans University of Baltimore Magazine SNAPSHOT Artscape 2017 This past July marked the 36th year for Baltimore’s Artscape festival, held in the neighborhoods surrounding UB. The three-day annual event attracts more than 350,000 attendees. Featured are visual art exhibits and live performances highlighting the work of more than 150 artists, including crafters, sculptors, photographers, dancers and musicians. UB’s unique contribution to the festivities is Gamescape, a program showcasing video games and the creative people who produce them. Held in Gordon Plaza, Gamescape gives visitors the opportunity to browse and interact with selected new games from local and national developers, as well as revisit a few classic favorites. PRESIDENT’S PAGE Publisher Magazine Office of Institutional Advancement University of Baltimore Executive Editor Kate Crimmins Assistant Editor Alli Hedden, M.A. ’14 Managing Editor Paula Novash Art Direction Skelton Design Photographers/Illustrators Peter Grundy Chris Hartlove Howard Korn Shae McCoy Chris Myers CHRIS HARTLOVE CHRIS Contributing Writers Christianna McCausland Dear UB Alumni and Friends: Vicki Meade Lynn Auld Schwartz Sometimes we don’t recognize moments of lasting importance in our lives while they are Staff Contributors Emily Brungo happening. A chance conversation may cause you to view a problem as an opportunity. Adam Leatherman Hearing a story about someone you disagree with may help you to see that you have Stacey Marriott, M.A. ’11 Tim Paggi, M.F.A. ’15 more in common than you previously thought. -

Pre-Professional Programs 77

77_PreProfessional_Pre-Professional 5/9/18 2:04 PM Page 77 Pre-professional Programs Pre-professional Programs Pre-professional Programs www.salisbury.edu/academic PRE-LAW PREPARATION HEALTH PROFESSIONS Pre-law Advisor ADVISORY PROGRAM (HPAP) Adam Hoffman, J.D., Ph.D.; Political Science Department John Lee, Ph.D., Director www.salisbury.edu/politicalscience/prelaw.html Henson School of Science and Technology www.salisbury.edu/henson/hpap In recent years SU graduates have been admitted to law [email protected] schools at American University, University of Baltimore, Catholic University, University of Maryland, Georgetown, Students interested in pursuing careers in the health George Washington University, Washington University, William professions have several options. and Mary, Widener University and others. Salisbury University has undergraduate majors and programs SU supports student efforts to achieve careers in law in a that lead directly to health care employment. These include: variety of ways. As recommended by the American Bar • Medical Laboratory Science Association, SU supports students to choose a major based on • Nursing their interests and their abilities. Students gaining admittance • Respiratory Therapy to law school are drawn from all areas of the University. While Health-related majors and programs include: concentrated in the Fulton School’s majors, students also • Community Health come from the Perdue, Henson and Seidel schools. • Exercise Science SU’s prelaw program helps all students design their • Social Work programs to achieve the skills necessary for success on the Law Students who do not plan on going directly into health School Admission’s Test (LSAT), with the application process care but are interested in post-graduate study in schools for and for success in law school. -

American University Washington College of Law Basic

American University Washington College of Law https://www.wcl.american.edu/career Basic Information Admissions Profile (J.D. Candidates only) 4801 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Applications received 5186 Washington, District of Columbia (DC), 20016-8181 Size of entering class: 429 United States # of undergraduate colleges represented: 211 202-274-4000 # of states represented (incl. D.C.) 42 In-state enrollment: n/a Career Service Administrator: Out-state enrollment: n/a Foreign countries represented: 11 Traci Mundy Jenkins, Esq. Assistant Dean, Career & Professional Development Grade Point Average / Law School Admission Test Phone: 202-274-4090 25th% 50th% 75th% [email protected] Grade Point Average Full-Time 3.15 3.37 3.54 Registrar: Grade Point Average Part-Time 2.98 3.33 3.50 Rebecca Davis, Assistant Dean & Registrar Grade Point Average Overall 3.13 3.37 3.54 202-274-4080 Law School Admission Test Full-Time 152 156 159 Law School Admission Test Part-Time 152 154 157 Contact Information for Other Career Services Staff Law School Admission Test Overall 152 156 158 Matthew Pascocello, Director Career Development & Alumni Counseling; Melanija Radnovic, Assistant Director of International Career Programs; Laura Scott, Assistant Director, Public Service Careers; Carey Yuill, Manager of Employer Relations; Kelly Noble, Judicial Clerkship Advisor; Arielle Pacer, In determining GPA and LSAT averages, are all students included? No Career Counselor; Tiffany Simmons, Career Counselor & Diversity Liaison; If not, what percentage is not included -

A Unique State Identification (SIC) Code for Each Institution

Maryland Higher Education Commission Data Dictionary ELEMENT TITLE: SIC DEFINITION: A unique state identification (SIC) code for each institution. These are assigned by MHEC. FORMAT: numeric - 6 digits CODES: see next page COMMENTS: The code is a structured code consisting of three elements: • first-digit o sector (SECTOR) o - institution ownership: 1=public2=private • second digit o - segment (SEGMENT) o - education segment:1 =community college o 2=University of Maryland4=Morgan5=St. Mary’s06=independent colleges and universities7=private career schools • third-sixth digit-institution id (INSTID) - unique 4 digit institution number RELATED TO: FICE GLOSSARY: SYSTEMS: MHEC use only SYSNAME: SIC DOCUMENTED: 1/1/80 Revised: 6/30/03, 10/10/2013 -DD7- 15 Maryland Higher Education Commission Data Dictionary Listing of Active SICs 110100 Allegany College of Maryland 110200 Anne Arundel Community College 110770 Carroll Community College 110900 Cecil Community College 111000 College of Southern Maryland 111100 Chesapeake College 111250 Community College of Baltimore County 111300 Baltimore City Community College 111700 Frederick Community College 111900 Garrett College 112100 Hagerstown Community College 112200 Harford Community College 112400 Howard Community College 111250 Community College of Baltimore County 112970 Montgomery College 113600 Prince George’s Community College 115470 Wor-Wic Community College 120600 Bowie State University 121400 Coppin State University 121800 Frostburg State University 123900 Salisbury University 124200 Towson University 124400 University of Baltimore 124500 Univ. of MD – Baltimore 124600 Univ. of MD – Baltimore County 124700 Univ. of MD – College Park 124800 Univ. of MD – Eastern Shore 124900 Univ. of MD – University College 124950 Univ. of MD – System Office 143000 Morgan State University 154000 St. -

“ Collegetown Leadershape Ignited My Passion for Creating Positive

Anne Rubin Anne Towson University University Towson Randi Lindsey Randi UMBC UMBC Skyler McCormick Skyler MICA MICA (pictured at right, first on left) on first right, at (pictured Cindy Greenwood Cindy Maryland Institute College of Art Art of College Institute Maryland Robert Penn, Penn, Robert – UMBC UMBC identity and energy.” and identity Kristin Baione Kristin Stevenson University University Stevenson Baltimore’s diverse, quirky quirky diverse, Baltimore’s Brandon Dulany Brandon or parks that reflect reflect that parks or McDaniel College College McDaniel Alycia Johnston Johnston Alycia farms, community gardens, gardens, community farms, Goucher College College Goucher Robert Penn Robert vacant lots into urban urban into lots vacant MICA MICA shared spaces – converting converting – spaces shared Pictured: gardens in vacant lots. vacant in gardens communities together in in together communities Painting signs for community community for signs Painting y vision is to bring bring to is M “ vision y ART WITH A HEART HEART A WITH ART SERVICE and eventually my students.” my eventually and life – with family, friends, coworkers, coworkers, friends, family, with – life relationships in many aspects of of aspects many in relationships will help me foster and sustain sustain and foster me help will during Collegetown LeaderShape LeaderShape Collegetown during (pictured inside at top right, fifth from left) from fifth right, top at inside (pictured he relationships I established established I T relationships “ he Notre Dame of Maryland University -

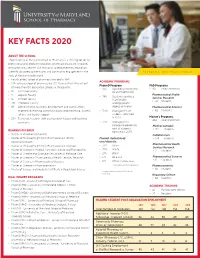

Key Facts 2020

KEY FACTS 2020 ABOUT THE SCHOOL The University of Maryland School of Pharmacy is a thriving center for professional and graduate education, pharmaceutical care, research, and community service. Our mission is to lead pharmacy education, scientific discovery, patient care, and community engagement in the EXPERTISE. INFLUENCE. IMPACT. state of Maryland and beyond. • Fourth oldest school of pharmacy founded in 1841 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS • 14th ranked school of pharmacy by U.S. News & World Report out PharmD Program PhD Programs of more than 130 accredited schools in the country. • 552 Applications received • 90 Total enrollment • 87 Full-time faculty for 2019 admission • 3 Adjunct faculty Pharmaceutical Health • 78% Students admitted • 12 Affiliate faculty Services Research in 2019 with • 28 Students • 796 Preceptor faculty undergraduate • 84 Administrative, business, development and alumni affairs, degree or higher Pharmaceutical Sciences experiential learning, communications and marketing, student • 3.40 Average GPA of • 62 Students affairs, and faculty support students admitted Master’s Programs • 254 Technical, research staff, postdoctoral fellows and teaching in 2019 • 462 Total enrollment assistants • 77% Average PCAT composite percentile Medical Cannabis rank of students • 152 Students DEGREES OFFERED admitted in 2019 • Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) Palliative Care • Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Pharmaceutical Health PharmD student body • 178 Students Services Research race/ethnicity: Pharmaceutical Health • Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in -

University of Baltimorefor ALUMNI and FRIENDS • FALL 2015 MAGAZINE

university of baltimoreFOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS • FALL 2015 MAGAZINE Seeds of Change Battling Baltimore’s Food Deserts Inside: Rocking the Vote / Come Sail Away / Go Clubbing PUBLISHER snapshot University of Baltimore Beautiful Minds Office of Alumni and Donor Services ASSISTANT VICE PRESIDENT For four days in late July and early part” as well as lectures, a movie FOR ALUMNI AND DONOR SERVICES AND EXECUTIVE EDITOR August, the University of festival, poetry readings and Kate Crimmins Baltimore welcomed more than musical performances. The MANAGING EDITOR 300 participants—ranging from conference also opened its doors Catherine Leidemer, M.A. ’11 CHRYSTAL JJ PHOTOGRAPHY: mathematicians, architects to the public for a free Family Day, ASSOCIATE EDITOR and computer scientists to artists, which gave attendees of all ages Giordana Segneri, M.A. ’10 educators, musicians, dancers and the chance to experience firsthand ASSISTANT EDITOR weavers—from 25 countries for the the exhibited collision of math, art Libby Zay Bridges Baltimore 2015 conference. and science through workshops, ART DIRECTOR This annual event, which changes games and more. Gigi Boam host cities each year, “celebrates the GRAPHIC DESIGNERS synthesis of math, art and science, pictured: The conference’s JJ Chrystal Sarah Davis [which is] engaging and fun,” says mathematical art exhibition Audra Harvey, M.A. ’11 organizer and faculty coordinator included “The {3,12} Polyhedron Katie Watkins Sujan Shrestha, assistant professor Decorated with a Fractal Circle PHOTOGRAPHERS/ILLUSTRATORS in the Division of Science, Information Pattern” (2015) by Doug Dunham, Jim Burger JJ Chrystal Arts and Technologies in UB’s Yale professor in the Department of Kate Crimmins Gordon College of Arts and Sciences. -

Transcript Guide for Enrollments from 2000-01 Academic Year to Present

Transcript Guide For Enrollments from 2000-01 Academic Year to Present GENERAL INFORMATION Course Division Codes General Information for AS and EN Effective Fall 2011, when the new grade is recorded, the 1. S/U Grades (freshmen) –Prior to Fall 2017, freshmen first original grade remains along with the notation “R” to indicate This guide is for interpreting symbols or codes shown on JHU Codes are as follows: transcripts for the following divisions of Johns Hopkins semester grades are not reported on the transcript. Each course the course was retaken, and the original grade does not affect AS Arts and Sciences with a grade of C- or above is assigned the letter S (for grade point calculations, nor does it carry credit toward University: BU Business Satisfactory) in place of a grade. Letter grades below C- are graduation. ED Education assigned the letter U (for Unsatisfactory). In the first semester Full-time: EN Engineering of a student's freshman year, credit is awarded for S grades. Prior to Fall 2011, when the new grade was recorded, the old Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences (AS) ME Medicine grade was replaced with the letter R to indicate the course was Whiting School of Engineering (EN) NR Nursing Prior to Fall 2017, for the first semester freshman year only, retaken. Part-time: PH Public Health credits are also awarded for U grades if the actual grade is D or Krieger - Advanced Academic Programs (AAP) PY Peabody Conservatory D+. In this instance the grade of UCR is assigned. No first 4. Graduate Retake Policy - At the discretion of the graduate Whiting - Engineering for Professionals (EP) SA School of Advanced International Studies semester grades are included in a student's cumulative grade- program, a graduate student may retake a course, but the grade point average. -

University of Baltimore Law Library

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgUNIVERSITY OF hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyBALTIMORE LAW uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgLIBRARY hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyUSERS’ GUIDE uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg 2011-2012 hjklzxcvbnmqwertyu iopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfxcvbn qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiop 1 asdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjkl zxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnm Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 1 LIBRARY HOURS ................................................................................................................................. 1 TELEPHONE NUMBERS ....................................................................................................................... 2 LIBRARY STAFF ................................................................................................................................... 2 LIBRARY HONOR RULES ...................................................................................................................... 3 CIRCULATION POLICY & FINES ........................................................................................................... -

UB-JHU Fellowship: Community Archives Program

UB-JHU Community Archives Fellowship 2021 Call for Applications MISSION STATEMENT The UB-JHU Community Archives Fellowship is a joint program of Johns Hopkins’ Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts and the University of Baltimore Special Collections and Archives designed to increase African American/Black presence in cultural heritage and archival fields. BACKGROUND Founded in 2017, the mission of the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts (BHPLA) is to document and disseminate the unique history of African American life, letters, and art in Baltimore, Maryland, and to foster intellectual linkages between the Johns Hopkins Homewood campus and the historic “inner city” of Baltimore. The University of Baltimore (UB) Special Collections and Archives specializes in 20th-century Baltimore history collections and provides access to archival materials in all formats to support the research needs of students, scholars, and the public. Through the fellowship program and collaborative engagement activities, the broad goals of the UB-JHU partnership are to: 1. Process endangered historical records documenting the lived experiences of Black Baltimoreans 2. Build grassroots stewardship capacity in reclaiming and preserving rare historical assets by providing direct technical assistance to Black cultural and faith-based institutions in Baltimore City 3. Train emerging cultural heritage workers in methods of culturally-appropriate community engagement for the cultivation and preservation of African American historical artifacts FELLOWSHIP SUMMARY The UB-JHU Community Archives Fellowship is a training fellowship designed to expose recent HBCU graduates and early career professionals of African/Black descent to careers in cultural heritage, archival management, library sciences, applied social and historical research, historic preservation and curatorship. -

The Fannie Angelos Program for Academic Excellence

University of Baltimore School of Law THE FANNIE ANGELOS PROGRAM FOR ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE 2018 Application Requirements The Fannie Angelos Program for Academic Excellence is a highly selective program run by the University of Baltimore School of Law that helps find qualified students and alumni at Maryland’s four Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) and other select Maryland public colleges and universities (University of Baltimore, Towson University, Salisbury University and the Universities at Shady Grove) and prepares them for law school. The Program has two components; Angelos Scholars and the LSAT Award Program. HBCU students who meet the requirements may apply for either or both programs. University of Baltimore, Towson University, Salisbury University and the Universities at Shady Grove students who meet the requirements may apply for the LSAT Award Program only. Please read the requirements very carefully §1 Angelos Scholars Program Open to HBCU Junior and Senior Year Students Only APPLICATION DEADLINE: October 15 Angelos Scholars who complete the program successfully, maintain a cumulative undergraduate grade point average of 3.5 out of 4.0, attain a score of 152 or higher on the LSAT and otherwise qualify for admission to the law school receive a full tuition scholarship to the University of Baltimore School of Law. The Angelos Scholars Program is open only to Bowie State, Coppin State, Morgan State, and UMES juniors, seniors, and other students who will be graduating from those HBCUs by Spring 2019. Scholars who successfully complete the Program will earn three academic credits towards their undergraduate graduation. Because the requirement for the full tuition scholarship is a GPA of at least 3.5 and a Law School Admission Test (LSAT) score of at least 152, applicants must either currently have at least a 3.5 GPA or explain why they expect to have a 3.5 GPA when they graduate. -

University System of Maryland

UNIVERSITY SYSTEM OF MARYLAND {USM Constituent Institutions} Salisbury University is a member of the University System of Maryland (USM). In addition to Salisbury University, constituent institutions in the University System of Maryland include: Bowie State University Coppin State University Frostburg State University Towson University University of Baltimore University of Maryland, Baltimore University of Maryland, Baltimore County University of Maryland, College Park University of Maryland, Eastern Shore University of Maryland, University College Research Centers: University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute System-wide Education Centers: USM Shady Grove Education Center, Montgomery County The University System of Maryland is governed by a Board of Regents and all relevant. Board of Regents policies apply to Salisbury University. {USM Bylaws, Policies and Procedures} The Board of Regents BOR of the University System of Maryland has the responsibility for man aging the System under Title 12 of the Education Article of the Maryland Annotated Code. In order to carry out this responsibility the Board has developed regulations for the System and published these in the document entitled Bylaws, Policies and Procedures of the Board of Regents: University System of Maryland. This information is online and can be located at: http://www.usmd.edu/regents/bylaws/bylaws.html. The president and the administration of Salisbury University manage the institution by implementing institutional policies and procedures that reflect both the requirements of the Board of Regents of the University System of Maryland and the unique character of Salisbury University. Salisbury University’s policies and procedures are presented on the following pages. At the end of each policy is a code indicating the Board of Regents' policy to which it relates.