An Art-Historical Travelogue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heather Buckner Vitaglione Mlitt Thesis

P. SIGNAC'S “D'EUGÈNE DELACROIX AU NÉO-IMPRESSIONISME” : A TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY Heather Buckner Vitaglione A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of MLitt at the University of St Andrews 1985 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13241 This item is protected by original copyright P.Signac's "D'Bugtne Delacroix au n6o-impressionnisme ": a translation and commentary. M.Litt Dissertation University or St Andrews Department or Art History 1985 Heather Buckner Vitaglione I, Heather Buckner Vitaglione, hereby declare that this dissertation has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been accepted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a candidate for the degree of M.Litt. as of October 1983. Access to this dissertation in the University Library shall be governed by a~y regulations approved by that body. It t certify that the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations have been fulfilled. TABLE---.---- OF CONTENTS._-- PREFACE. • • i GLOSSARY • • 1 COLOUR CHART. • • 3 INTRODUCTION • • • • 5 Footnotes to Introduction • • 57 TRANSLATION of Paul Signac's D'Eug~ne Delac roix au n~o-impressionnisme • T1 Chapter 1 DOCUMENTS • • • • • T4 Chapter 2 THE INFLUBNCB OF----- DELACROIX • • • • • T26 Chapter 3 CONTRIBUTION OF THE IMPRESSIONISTS • T45 Chapter 4 CONTRIBUTION OF THB NEO-IMPRBSSIONISTS • T55 Chapter 5 THB DIVIDED TOUCH • • T68 Chapter 6 SUMMARY OF THE THRBE CONTRIBUTIONS • T80 Chapter 7 EVIDENCE • . • • • • • T82 Chapter 8 THE EDUCATION OF THB BYE • • • • • 'I94 FOOTNOTES TO TRANSLATION • • • • T108 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • T151 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 1. -

Liste À Publier 25 Janvier 2017.Pdf

_ ERP de Seine-Maritime qui se sont déclarés comme étant accessibles par leur gestionnaire/propriétaire aux règles d’accessibilité (attestation d’accessibilité ou cerfa 15247) – Mise à jour de la liste 31/12/2016 Adresse de l’ERP 1 SIRET Catégorie Numéro de 5 Nom de l’établissement Type d’ERP 2 Nom gestionnaire/propriétaire ou Date de dépôt d’ERP l’attestation 4 DATE DE NAISSANCE Rue Code postal COMMUNE 7 Auto école MACADAM CONDUITE 2 place du Tilleul 76190 ALLOUVILLE BELLEFOSSE 5 R AC-076-000700 CARLE Jérôme 53954774500023 09/06/2015 Le Pousserdas 2 rue Jacques Anquetil 76190 ALLOUVILLE BELLEFOSSE 5 M-N AC-076-003350 Non DEHAIS Dominique 80842135800017 29/01/2016 Pharmacie du Chêne 18 rue Jacques Anquetil 76190 ALLOUVILLE BELLEFOSSE 5 M AC-076-003717 Non PETIT Carine 50075159200012 06/03/2015 Eglise rue des Tilleuls 76640 ALVIMARE 5 V AC-076-002393 Non LEMERCIER Michel 21760002200016 28/09/2015 Garage Blondel 44 RD 6015 76640 ALVIMARE 5 M AC-076-003443 Non BLONDEL Léo 35076381900017 08/06/2016 Salle communale 3 route de la Chapelle 76640 ALVIMARE 5 L AC-076-002394 Non LEMERCIER Michel 21760002200016 28/09/2015 L’Ancienne Mare rue de l’Ancienne Mare 76550 AMBRUMESNIL 5 M AC-076-003145 Non PATE Philippe 45179779900017 30/06/2016 Bowling Billard Anfreville 177 route de Paris 76920 AMFREVILLE LA MIVOIE 4 P AC-076-004354 Oui SARL BBA – EL MNRRETAR Aicha 43176378800012 23/09/2015 Cabinet d’infirmières 59 rue F.Mitterand / Rés. Sente des près 76920 AMFREVILLE LA MIVOIE 5 U AC-076-001263 Non HOJNACKI-BUQUET 40856764200025 11/03/2015 Kinésithérapeute -

Allouville Bellefosse A.S

ALLOUVILLE BELLEFOSSE A.S. ALLOUVILLE BELLEFOSSE 521219 Couleurs : Vert Et Noir Siège social : mairie Email officiel : [email protected] 76190 ALLOUVILLE BELLEFOSSE President : M. TALBOT Sylvain Correspondant : Mme RICARD Clemence Terrain : STADE JEAN-PIERRE CORDERON 47-29 Rue De Liernu 76190 ALLOUVILLE BELLEFOSSE AMFREVILLE LA MI VOIE A.S.ML. D'AMFREVILLE LA MIVOIE 538786 Couleurs : Rose Noir Siège social : RUE FRANCOIS MITTERAND Site internet : asmla.footeo.com MAIRIE Email officiel : [email protected] 76920 AMFREVILLE LA MI VOIE President : M. D'ABREU Stephane Correspondant : M. ZAMMIT Romain Terrain : STADE ROBERT TALBOT 1 Terrain A Quai Lescure 76920 AMFREVILLE LA MI VOIE ANGERVILLE L ORCHER A.S. ANGERVILLE L'ORCHER 501611 Couleurs : Rouge Siège social : MAIRIE Email officiel : [email protected] 76280 ANGERVILLE L ORCHER Site internet : club.sportsregions.fr/asao-foot President : M. BAIET Benjamin Correspondant : M. GOUZIEN Donovan Mob. personnel : 0668172693 170 Rue Du Presbytère Email officiel : [email protected] 76110 ST SAUVEUR D EMALLEVILLE Email principal : [email protected] Terrain : STADE MUNICIPAL Rue Des Hellandes 76280 ANGERVILLE L ORCHER ANGERVILLE LA MARTEL AS COLLEVILLE ANGERVILLE 582389 Couleurs : Bleu Et Blanc Siège social : MAIRIE Email officiel : [email protected] 1 le BOURG Email autre : andre- 76540 ANGERVILLE LA MARTEL [email protected] Mob. personnel : 06 48 33 04 89 President : M. DESCHAMPS Regis Correspondant : M. VAUCHEL Johann ANNEVILLE AMBOURVILLE U.S. DE LA PRESQU ILE 546932 Couleurs : Rouge Siège social : MAIRIE Email officiel : [email protected] 76480 ANNEVILLE AMBOURVILLE Email principal : [email protected] Site internet : uspi.footeo.com President : M. MOTTIN PERROTTE Sebastien Correspondant : M. -

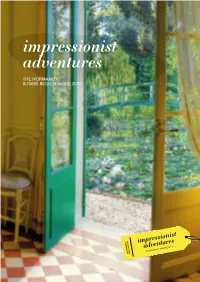

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

Download Lot Listing

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART Wednesday, May 10, 2017 NEW YORK IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART EUROPEAN & AMERICAN ART POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART AUCTION Wednesday, May 10, 2017 at 11am EXHIBITION Saturday, May 6, 10am – 5pm Sunday, May 7, Noon – 5pm Monday, May 8, 10am – 6pm Tuesday, May 9, 9am – Noon LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $40 INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART 1-118 Elsie Adler European 1-66 The Eileen & Herbert C. Bernard Collection American 67-118 Charles Austin Buck Roberta K. Cohn & Richard A. Cohn, Ltd. POST-WAR & CONTEMPORARY ART 119-235 A Connecticut Collector Post-War 119-199 Claudia Cosla, New York Contemporary 200-235 Ronnie Cutrone EUROPEAN ART Mildred and Jack Feinblatt Glossary I Dr. Paul Hershenson Conditions of Sale II Myrtle Barnes Jones Terms of Guarantee IV Mary Kettaneh Information on Sales & Use Tax V The Collection of Willa Kim and William Pène du Bois Buying at Doyle VI Carol Mercer Selling at Doyle VIII A New Jersey Estate Auction Schedule IX A New York and Connecticut Estate Company Directory X A New York Estate Absentee Bid Form XII Miriam and Howard Rand, Beverly Hills, California Dorothy Wassyng INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM A Private Beverly Hills Collector The Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz sold for the benefit of the Bard Graduate Center A New England Collection A New York Collector The Jessye Norman ‘White Gates’ Collection A Pennsylvania Collection A Private -

Im Pressio Nist M O Dern & Co Ntem Po Rary Art 27 January

IMPRESSIONIST MODERN & CONTEMPORARY ART CONTEMPORARY & MODERN IMPRESSIONIST 27 JANUARY 2015 8 PM 8 2015 JANUARY 27 27 JANUARY 2015 PM 8 2015 JANUARY 27 134 IMPRESSIONIST MODERN & CONTEMPORARY ART CONTEMPORARY & MODERN IMPRESSIONIST VIEWINGS: Thu 15 Jan 5 pm - 10 pm Fri 16 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sat 17 Jan 10 pm - 12 am IMPRESSIONISSun - Thu /T 18-22, MO JanDERN 11 am - 10 pm Fri 23 Jan 11 am - 3 pm & CONSat T24EMPORAR Jan Y 10 pm - 12 am Sun - Mon / 25 - 26 Jan 11 am - 10 pm FINE TueAR 27T JanAUCTION 11 am - 8 pm JERUSALEM, JANUARY 27, 2015, 8 PM SALE 134 PREVIEW IN JERUSALEM: Thu 15 Jan 5 pm - 10 pm Fri 16 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sat 17 Jan 10 pm - 12 am Sun - Thu / 18-22 Jan 11 am - 10 pm Fri 23 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sat 24 Jan 10 pm - 12 am Sun - Mon / 25 - 26 Jan 11 am - 10 pm Tue 27 Jan 11 am - 8 pm PREVIEW IN NEW YORK: Thu 15 Jan 12 pm - 5 pm Fri 16 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sun - Thu / 18-22 Jan 12 pm - 5 pm Fri 23 Jan 11 am - 3 pm Sun - Mon / 25 - 26 Jan 12 pm - 5 pm Tue 27 Jan 11 am - 1 pm PREVIEW & AUCTION MATSART GALLERY 21 King David St., Jerusalem tel +972-2-6251049 www.matsart.net בס"ד MATSART AUCTIONEERS & APPRAISERS 21 King David St., Jerusalem 9410145 +972-2-6251049 5 Frishman St., Tel Aviv 6357815 +972-3-6810001 415 East 72 st., New York, NY 10021 +1-718-289-0889 LUCIEN KRIEF OREN MIgdAL Owner, Director Head of Department Expert Israeli Art [email protected] [email protected] StELLA COSTA ALICE MARTINOV-LEVIN Senior Director Head of Department [email protected] Modern & Contemporary Art [email protected] EVGENY KOLOSOV YEHUDIT RATZABI AuctionAdministrator AuctionAdministrator Modern & Contemporary Art [email protected] [email protected] REIZY GOODWIN MIRIAM PERKAL Logistics & Shipping Client Accounts Manager [email protected] [email protected] All lots are sold “as is” and subject to a reserve. -

Artist Spotlight

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT Édouard Manet DAN SCOTT The Bridge BetweenÉdouard Realism Manet and Impressionism Édouard Manet (1832-1883) was a French painter who bridged the gap between Real- ism and Impressionism. In this ebook, I take a closer look at his life and art. Édouard Manet, Boating, 1874 2 Key Fact Here are some of the key facts and ideas about the life and art of Manet: • Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was fortunate enough to be born into a wealthy family in Paris on 23 January 1832. His father was a high-ranking judge and his mother had strong political connections, being the daughter of a diplomat and goddaughter of Charles Bernadotte, a Swedish crown prince. • His father expected him to follow in his footsteps down a career in law. However, with encouragement from his uncle, he was more interested in a career as a paint- er. His uncle would take him to the Louvre on numerous occasions to be inspired by the master paintings. • Before committing himself to the arts, he tried to join the Navy but failed his entry examination twice. Only then did his father give his reluctant acceptance for him to become an artist. • He trained under a skilled teacher and painter named Thomas Couture from 1850 to 1856. Below is one of Couture’s paintings, which is similar to the early work of Manet. I always find it interesting to see how much a teacher’s work can influence the work of their students. That is why you need to be selective with who you learn from. -

O Ex, O -4-» 0)

o ex, o -4-» 0) CO H CO I—zI o p—I CO CO w P4 Terrace at Sainte-Adresse, by Claude Monet (1840-1926), Trench. About 1867. Oil on canvas, 38%, x S'Vs inches. Purchased with special contributions and purchase funds given or bequeathed by friends of the Museum, (>~.2ji Windows Open to Nature MARGARETTA M. SALINGER Associate Curator of European Paintings "Sainte-Adresse," wrote Monet in the early sixties, alluding to the physical aspect of the little seacoast town north of Le Havre and not to his frustrated life there among his exasperated relatives, "Sainte-Adresse - it's heavenly and every day I turn up things that are constantly more lovely. It's enough to drive one mad, I so much want to do it all!" This joyous appreciation, this impatient eagerness, from the most objective and consciously directed of the impressionist painters is echoed twenty-five years later in the bursting enthusiasm of one of Vincent van Gogh's letters written from Aries: "Nature here is so extraordinarily beautiful... I cannot paint it as lovely as it is." What other movement in the whole history of art is so marked by cheerfulness or reflects so much pure delight in life and nature as impressionism? The subject matter alone in dicates the happy things that attracted the young artists: pretty women, children, and pets; places of amusement - theaters, circuses, outdoor dance halls, regattas and sailing parties, restaurants and cafes; and most of all, nature herself, beaches and rivers, flowers and gardens. The question automatically arises why, confronted with so many agree able images, public and critics alike were outraged by what they saw, most of the latter nettled to the point of searing hostility. -

Albert Lebourg 1849-1929

Albert Lebourg 1849-1929 Canal in Holland Oil on canvas / signed and dated 1896 lower left Dimensions : 39 x 55 cm Dimensions : 15.35 x 21.65 inch 32 avenue Marceau 75008 Paris | +33 (0)1 42 61 42 10 | +33 (0)6 07 88 75 84 | [email protected] | galeriearyjan.com Albert Lebourg 1849-1929 32 avenue Marceau 75008 Paris | +33 (0)1 42 61 42 10 | +33 (0)6 07 88 75 84 | [email protected] | galeriearyjan.com Albert Lebourg 1849-1929 Biography Born in the Eure department in Normandy, Albert Lebourg was only nineteen years old when he settled in Rouen to work with an architect. In the evening, he took painting and drawing lessons with Gustave Morin. Nevertheless, he quickly get bored of doing copies of antique plasters and prefered to paint outside, looking for inspiration in the surrounding countryside. In 1872, he was noticed by a collector who proposed him to become a drawing teacher at the Fine Arts school in Algiers, where he stayed for five years. During this time, Albert Lebourg devoted himself to painting, inspired by the light variations. He liked to paint l'Amirauté, its embankments and its green balconies, the mosque Jamaa al-Jdid, also named mosque of the Pêcherie, and the little streets of the white city. Lebourg often painted the same motifs at different moments of the day. His palette brightened and his style was completely impressionnist. However, the artist was still ignorant of this new artistic movement that he will discover when he got back in France in 1877. -

Pierre DUMONT (JALLOT) Painting 20Th Seated Woman Oil Signed

anticSwiss 26/09/2021 02:53:37 http://www.anticswiss.com Pierre DUMONT (JALLOT) Painting 20th Seated Woman Oil signed FOR SALE ANTIQUE DEALER Period: 20° secolo - 1900 Violon d'Ingres Saint Ouen Style: Arte Moderna +33 06 20 61 75 97 330620617597 Height:46cm Width:65cm Price:2800€ DETAILED DESCRIPTION: Pierre DUMONT, pseudonym JALLOT, (1884/1936) Young woman sitting in a seaside landscape. Oil on canvas signed lower left. 46 x 65 cm DUMONT Pierre, Born March 29, 1884 in Paris / Died April 9, 1936 in Paris. Painter of landscapes, urban landscapes, seascapes, still lifes, flowers. Expressionist. Pierre DUMONT is one of the most original and most unknown painters of the Rouen school. Having come to Paris at a very young age, Pierre DUMONT lived there poorly in the La Ruche district, then returned to Rouen around 1905, he painted very colorful landscapes, in an oily and thick paste spread out on the canvas as if he was sculpting his vision. To contain his "Fauve" temperament, Pierre DUMONT entered the Rouennaise Academy of Joseph Delattre, then founded with friends artists and writers the group of XXX which became in 1909 the Norman Society of modern painting. His first paintings were marked by the influences of Van Gogh and Cézanne. From around 1910 Pierre DUMONT began to paint Rouen cathedral, from 1914 to 1919 he mainly painted the streets of Montmartre, Notre Dame cathedral, the bridges of Paris and the banks of the Seine. From 1911 to 1916, Pierre DUMONT lived at the Bateau-Lavoir where he became friends with Picasso who kept a workshop there. -

The Artists of Les Xx: Seeking and Responding to the Lure of Spain

THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESPONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI (Under the Direction of Alisa Luxenberg) ABSTRACT The artists’ group Les XX existed in Brussels from 1883-1893. An interest in Spain pervaded their member artists, other artists invited to the their salons, and the authors associated with the group. This interest manifested itself in a variety of ways, including references to Spanish art and culture in artists’ personal letters or writings, in written works such as books on Spanish art or travel and journal articles, and lastly in visual works with overtly Spanish subjects or subjects that exhibited the influence of Spanish art. Many of these examples incorporate stereotypes of Spaniards that had existed for hundreds of years. The work of Goya was particularly interesting to some members of Les XX, as he was a printmaker and an artist who created work containing social commentary. INDEX WORDS: Les XX, Dario de Regoyos, Henry de Groux, James Ensor, Black Legend, Francisco Lucientes y Goya THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESPONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI Bachelor of Arts, Manhattanville College, 1999 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2005 © 2005 CAROLINE CONZATTI All Rights Reserved THE ARTISTS OF LES XX: SEEKING AND RESONDING TO THE LURE OF SPAIN by CAROLINE CONZATTI Major Professor: Alisa Luxenberg Committee: Evan Firestone Janice Simon Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia December 2005 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thanks the entire art history department at the University of Georgia for their help and support while I was pursuing my master’s degree, specifically my advisor, Dr. -

Paintings & Sculptures List – the Dining Room The

Russell-Cotes Paintings – The Dining Room Paintings & Sculptures List – The Dining Room The Fruit Seller Giuseppe Signorini (1857-1932) Watercolour, body colour and gum Arabic paper Giuseppe Signorini was an Italian painter, born in Rome, and mainly focused on orientalist subjects. He studied at the Accademia di San Luca, and then worked under Aurelio Tiratelli. He often travelled to the Paris Salon exhibitions and was influenced by the styles and orientalist themes expressed by painters like Mariano Fortuny, Ernest Meissonier, and Gérôme. He often travelled to the Maghreb for inspiration and developed a substantial collection of Islamic art and textiles. He also painted portraits in costume garb. He maintained studios in both Paris and Rome. BORGM 1995:66 The Billet Doux, 1882 William Oliver (1804-1853) Oil on canvas William Oliver was a painter of charming genre scenes, including titles such as A Thing of Beauty is a Joy Forever and The Billet Doux, and was one of the more popular Victorian artists of his time. Oliver was particularly fond of the Pyrenean area of France and Spain and completed many small Russell-Cotes Paintings – The Dining Room studies of the towns and villages in this area. Many of these small works were then purchased by the young travellers as souvenirs of their Grand Tour. While he favoured painting plein air works, he did complete a number of large and important works during his career – most of which were either created for specific exhibitions or commissions. BORGM 01686 Napoleon, 19th Century Sculptor unattributed Marble Merton Russell-Cotes cultivated people of high standing assiduously in real life as well as collecting them in the form of art works.