The Science That Fed Frankenstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Power of the Imagination~ Fall 2012 Division of Humanities—English University of Maine at Farmington

English 345 ~ English Romanticism: The Power of the Imagination~ Fall 2012 Division of Humanities—English University of Maine at Farmington Instructor: Dr. Misty Krueger Office: 216A Roberts Learning Center Office Hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10 a.m.-11 a.m. and 2:30 p.m.-3:30 p.m. Office Phone: 207-778-7473 E-mail: [email protected] (preferred method of contact) COURSE DESCRIPTION Welcome to this course, which will cover the English Romantic period (1785-1832). Notable writers from this period include Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, the Shelleys, and John Keats, among many others. In this course we will explore how their works react to important contemporary political events, reconstruct a gothic past, draw on the supernatural, and incorporate spontaneity and imagination. Our specific goal in this course is to study how the ‘powers of the imagination’ lead some of the most well-known Romantic authors to craft brilliant and inventive essays, fiction, poetry, and dramatic literature. As such, we will spend our time examining these authors’ inspirations for writing, means of composition, and conceptions of the purpose of literature, as well as its effects on the individual and society-at-large. We are about to study some of the most beautiful literature ever written in the English language. Get ready to be inspired! Get ready to become an enthusiastic, active participant in this course by contributing discussion questions about our readings, completing reading responses, giving a formal class presentation on scholarly criticism, and conversing informally with your classmates about our course materials. -

DAL GOLEM ALLA CREATURA DI MARY SHELLEY: FRANKENSTEIN TRA MITO, SCIENZA E LETTERATURA Angela Articoni*

DAL GOLEM ALLA CREATURA DI MARY SHELLEY: FRANKENSTEIN TRA MITO, SCIENZA E LETTERATURA Angela Articoni* Mi concepì. Presi forma come un neonato, non nel suo corpo, ma nel suo cuore, mi sviluppai nella sua immaginazione finché trovai il coraggio di uscire dalla pagina e di entrare nella vostra mente. Lita Jugde1 Abstract: The similarity between Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the Golem of Jewish folklore is no mere coincidence. The Golem’s introduction on early nineteenth century German literature – ironically at the hands of two avowed anti˗Semites, Jacob Grimm and Ludwig Achim von Arnim – may have enabled the novelist Mary Shelley to rediscover it. In addition, being aware of the avant˗garde scientific research that was being carried out at the time, Mary Shelley also took inspiration from her many readings to incorporate mythological and theological debates related to science. Keywords: Golem, Frankenstein, Mary Shelley, Scientific discoveries, Gothic literature, Childrenʼs literature. Frankenstein ovvero il Prometeo moderno Il nome Prometeo, in greco Promethéus, significa “colui che riflette prima”, saggezza e intelligenza sono, infatti, le sue doti principali. È un titano di seconda generazione – figlio di Giapeto e di Climene, figlia di Oceano – sempre dalla parte degli uomini, in contrasto con il dio supremo Zeus, del quale rappresenta in un certo senso l’antitesi. Secondo Esiodo – nella * Dottore di ricerca in Scienze dell’Educazione - Università di Foggia. 1 Lita Jugde, Mary e il mostro. Amore e ribellione. Come Mary Shelley creò Frankenstein, trad. it. R. Bernascone, Il Castoro, Milano 2018, p. 7. 69 Teogonia (700 a.C. ca.) – Prometeo creò l’uomo con creta rinvenuta a Panopea, in Beozia, plasmando figure nelle quali Atena inalava la vita2. -

Download (1MB)

BYRON'S LETTERS AND JOURNALS Byron's Letters and Journals A New Selection From Leslie A. Marchand's twelve-volume edition Edited by RICHARD LANSDOWN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © In the selection, introduction, and editorial matter Richard Lansdown 2015 © In the Byron copyright material John Murray 1973-1982 The moral rights of the author have be en asserted First Edition published in 2015 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publicationmay be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writi ng of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press i98 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2014949666 ISBN 978-0-19-872255-7 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives pk in memory of Dan Jacobson 1929-2014 'no one has Been & Done like you' ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Two generations of Byron scholars, biographers, students, and readers have acknowledged the debt they owe to Professor Leslie A. -

Masters of the Mind

Masters of the Mind A Study of Vampiric Desire, Corruption, and Obsession in Polidori's The Vampyre, Coleridge's Christabel, and Le Fanu's Carmilla By Astrid van der Baan Astrid van der Baan 4173163 Department of English Radboud University Nijmegen Supervisor: Marguerité Corporaal 15 August 2016 van der Baan 4173163/1 Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude for the help and support that I received from people while writing my BA thesis. First, I would like to thank my supervisor Dr Marguérite Corporaal for her advice and guidance during this project. Next, I would like to thank Anne van den Heuvel, Irene Dröge and Tessa Peeters for their support and feedback. I could not have finished my thesis without you guys! van der Baan 4173163/2 Table of Content Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................... 1 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 The Vampyre (1819) ................................................................................................ 10 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Main Gothic elements in The Vampyre ......................................................................... -

From Diderot to Keats and Shelley

THE POLITICS OF DREAMING – FROM DIDEROT TO KEATS ming AND SHELLEY [ Dreaming, seemingly a private activity, can exhibit political and ideological dimensions. ALAN RICHARDSON ABSTRACT The first part of this article looks at the ideological significance, within late Enlighten- ment and Romantic-era culture, of the very activity of dreaming, with particular reference to Diderot’s Le Rêve de d’Alembert. Nocturnal dreaming and the somnambulistic behaviors closely associated with dreaming can and did challenge orthodox notions of the integral ] subject, of volition, of an immaterial soul, and even of the distinction between humans and animals. The second half of the article looks at two literary dreams, from the poetry of Shelley and Keats, considering how represented dreams can have pronounced ideological and political valences. The article as a whole illustrates the claims and methods of cognitive historicist literary critique. KEYWORDS Poetry, dreams, neurology, John Keats, P. B. Shelley. ‘In Dreams Begin Responsibilities’, Delmore Schwartz’s oblique and compact coming of age narrative, remains one of the most compelling American short stories of the last century. Its coolly seductive hold on the reader begins with its title, which Schwartz borrowed from an epigraph to W. B. Yeats’s poetic volume Responsibilities, ‘in dreams begins responsibility’, attributed by Yeats in turn to an ‘Old Play’ (98). Whatever the title’s ultimate provenance, its juxtaposition of dream and responsibility instantly sets us pondering: how could dreams, invol- untary, cryptic and unpredictable, generate anything like duties and obligations? The juxtaposition of politics and dreaming in this essay’s title seeks to pro- voke a similar unsettling of categories and rethinking of conceptual boundaries. -

English 363K E. M. Richmond-Garza MW 11:30-1 Par 204 Classic To

English 363K E. M. Richmond-Garza MW 11:30-1 Par 204 Classic to Romantic “Day Into Night” Spring 2017 I’m going to the darklands to talk in rhyme with my chaotic soul as sure as life means nothing and all things end in nothing and heaven I think is too close to hell The Jesus and Mary Chain, “darklands” § Intent of the Course How does European art and literature move from the fiery bright day of the eighteenth-century philosophes and neo-classical poets to the dark intensity of the height of Romanticism? How are the promise of rationalism, the hopes of the French Revolution and the elegant coolness of the idealized “Golden Age” of Hellenistic Greece transformed into the great passionate and ironic experiment of Romanticism? How can we account for and appreciate the extraordinary international artistic explosion around the year 1800 throughout Europe as artists and writers sought to go beyond what they saw as their betrayal by the previous generation’s exquisite plans? Treating a fin-de-siècle twilight and a new centiry’s dawn not unlike our own, this course will situate the art and literature of the English Romantics within the social, political, and aesthetic contexts of both Classicism and international Romanticism. We will look at the fine arts, especially painting and music, as well as the literary texts of the period. Dissatisfied with the neo-classical aesthetics and politics of Pope, Johnson, and Reynolds, even in the eighteenth century Blake in England and Diderot in France were already testing the Romantic waters. -

Paratextual and Bibliographic Traces of the Other Reader in British Literature, 1760-1897

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData Theses and Dissertations 9-22-2019 Beyond The Words: Paratextual And Bibliographic Traces Of The Other Reader In British Literature, 1760-1897 Jeffrey Duane Rients Illinois State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Educational Methods Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rients, Jeffrey Duane, "Beyond The Words: Paratextual And Bibliographic Traces Of The Other Reader In British Literature, 1760-1897" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 1174. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/etd/1174 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BEYOND THE WORDS: PARATEXTUAL AND BIBLIOGRAPHIC TRACES OF THE OTHER READER IN BRITISH LITERATURE, 1760-1897 JEFFREY DUANE RIENTS 292 Pages Over the course of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, compounding technological improvements and expanding education result in unprecedented growth of the reading audience in Britain. This expansion creates a new relationship with the author, opening the horizon of the authorial imagination beyond the discourse community from which the author and the text originate. The relational gap between the author and this new audience manifests as the Other Reader, an anxiety formation that the author reacts to and attempts to preempt. This dissertation tracks these reactions via several authorial strategies that address the alienation of the Other Reader, including the use of prefaces, footnotes, margin notes, asterisks, and poioumena. -

The Diary of Dr. John William Polidori, 1816, Relating to Byron, Shelley

THE DIARY OF BR, JOHN WILLIAM POUDORI WILLIAM MICHAEL ROSSETTI 4 OfarttcU Ittinerattg Slihrarg atljata, New ^nrh BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF HENRY W. SAGE 1891 MAY 3. l?*^ Inlciffimry loan I ^Q*^! ^P^ 7 ? Cornell UniversHy Library PR 5187.P5A8 William PoMo^^^^^ The diary of Dr. John 3 1924 013 536 937 * \y Cornell University Library The original of tliis bool< is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924013536937 The Diary of Dr. John William Polidori — The Diary of Dr. John WilHam Pohdori 1816 Relating to Byron, Shelley, etc. Edited and Elucidated by William Michael Rossetti "Mi fiir mostrat! gli spirit! magni Che del vederli in me stesso n'esalto." Dantk. LONDON ELKIN MATHEWS VIGO STREET MCMXI Richard Clav & Sons, Limited, bread street hill, e.c., and bungay, suppolk. sA#^ -0\N Y-ITvV iJf^ ^^ DEDICATED TO MY TWO DAUGHTERS HELEN AND MARY WHO WITH MY LITTLE GRAND-DAUGHTER IMOGENE- KEEP THE HOME OF MV CLOSING YEARS STILL IN GOOD CHEER The Diary of Dr. John WiUiam Polidori INTRODUCTION A PERSON whose name finds mention in the books about Byron, and to some extent in those about Shelley, was John William Polidori, M.D. ; he was Lord Byron's travelling physician in 1816, when his Lordship quitted England soon after the separa- tion from his wife. I, who now act as Editor of his Diary, am a nephew of his, born after his death. -

The Italian Verse of Milton May 2018

University of Nevada, Reno The Italian Verse of Milton A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Francisco Nahoe Dr James Mardock/Dissertation Advisor May 2018 © 2018 Order of Friars Minor Conventual Saint Joseph of Cupertino Province All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA, RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Francisco Nahoe entitled The Italian Verse of Milton be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY James Mardock PhD, Adviser Eric Rasmussen PhD, Committee Member Lynda Walsh PhD, Committee Member Donald Hardy PhD (emeritus), Committee Member Francesco Manca PhD (emeritus), Committee Member Jaime Leaños PhD, Graduate School Representative David Zeh PhD, Dean, Graduate School May 2018 i Abstract The Italian verse of Milton consists of but six poems: five sonnets and the single stanza of a canzone. Though later in life the poet will celebrate conjugal love in Book IV of Paradise Lost (1667) and in Sonnet XXIII Methought I saw my late espousèd saint (1673), in 1645 Milton proffers his lyric of erotic desire in the Italian language alone. His choice is both unusual and entirely fitting. How did Milton, born in Cheapside, acquire Italian at such an elevated level of proficiency? When did he write these poems and where? Is the woman about whom he speaks an historical person or is she merely the poetic trope demanded by the genre? Though relatively few critics have addressed the style of Milton’s Italian verse, an astonishing range of views has nonetheless emerged from their assessments. -

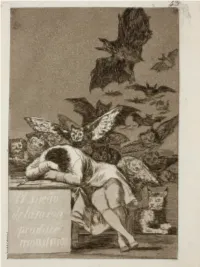

14 MÈTODE Museo DOCUMENT MÈTODE Science Studies Journal, 6 (2016): 14-20

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid 14 MÈTODE DOCUMENT MÈTODE Science Studies Journal, 6 (2016): 14-20. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.85.3481 ISSN: 2174-3487. Article received: 12/03/2014, accepted: 29/07/2014. THE SLEEP OF (SCIENTIFIC) REASON PRODUCES (LITERARY) MONSTERS OR, HOW SCIENCE AND LITERATURE SHAKE HANDS DANIEL GENÍS MAS Enlightened reason and romantic imagination were seen as two opposing ways of conceiving art and life. Today, from our historical vantage point, it is difficult to understand one without the other. As if the nightmares of science were nothing more than the food of romantic monsters. This article analyses the evolution of fantastic literature and the birth of scientific fiction in the nineteenth century, as well as the conflict between the rational and the supernatural. Keywords: Enlightenment, Romanticism, vampires, Frankenstein, science fiction. In 2013, the indefinable filmmaker Albert Serra n SCIENTIFIC REASON premiered Història de la meva mort (“The story of my death”), an original and controversial film that Voltaire (1694-1778), the philosopher who best imagines a meeting between the actual Italian libertine represents the spirit of Enlightenment and the Age of Giacomo Casanova (1725-1798), and Count Dracula, an Enlightenment, complained that between 1730 and invention of literary fiction. The film opens with the 1735 vampires were the only topic of conversation elderly Casanova who decides to leave France, home throughout Europe (Polidori, 2013). We know of of the Enlightenment, to retire in the Carpathians and several cases of late seventeenth and early eighteenth begin drafting his memoirs. In Serra’s film, Casanova century reports concerning a strange epidemic in embodies the values of the several towns in Serbia, Hungary, Enlightenment movement, whose Russia, Silesia and Poland. -

Conference Abstracts and Bios

KEYNOTE SPEAKERS WEDNESDSAY 31ST OCTOBER Frankenstein 2.0 Professor Nick Groom, University of Exeter, UK Biography: My work investigates questions of authenticity and the emergence of national and regional identities, particularly in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This interest began in my first book, a study of the formation of the English ballad tradition (The Making of Percy's Reliques, Clarendon Press, 1999) and an edition of Thomas Percy's collection of ballads (Routledge/Thoemmes Press, 1996). At the same time I published a collection of essays on the poet Thomas Chatterton (Thomas Chatterton and Romantic Culture, Macmillan, 1999), and used Chatterton as the central figure in a study of literary forgery and poetic inspiration, The Forger's Shadow (Picador, 2002; paperbacked 2003) - a book that also covered James Macpherson, William Henry Ireland, and Thomas Griffiths Wainewright. The Times Literary Supplement described The Forger's Shadow as ‘Refreshingly humanist and carefully researched ... the most entertaining, erudite and authoritative book on literary forgery to date.' Following these predominantly literary critical studies, my work has become more emphatically interdisciplinary. Most recently, a cultural history of The Union Jack (Atlantic, 2006; paperbacked 2007), has examined expressions of British identities. The Union Jack was described by the Times Higher Education Supplement as ‘Vivid, fascinating and carefully researched history... robust, positive and wholly persuasive', and by the Guardian as ‘essential reading'. This work on national identity and culture has inspired further research into the relationship of culture variously with the past, with noise, and with the landscape. My study on the history of representations of the English environment was published in November 2013 as The Seasons: An Elegy for the Passing of the Year (Atlantic). -

Bibliography

Bibliography Allott , Miriam (ed.) ( 1982 ), Essays on Shelley (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press). Angeli , Helen Rossetti ( 1911 ), Shelley and His Friends in Italy (London: Methuen). Arditi , Neil (2001 ), ‘T. S. Eliot and The Triumph of Life ’, Keats-Shelley Journal 50, pp. 124–43. Arnold , Matthew ( 1960 –77), The Complete Prose Works , ed. R. H. Super, 11 vols (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press). Bainbridge , Simon ( 1995 ), Napoleon and English Romanticism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). Baker , Carlos ( 1948 ), Shelley’s Major Poetry: The Fabric of a Vision (Princeton: Princeton University Press). Bandiera , Laura ( 2008 ), ‘Shelley’s Afterlife in Italy: From 1922 to the Present’, in Schmid and Rossington ( 2008 ), pp. 74–96. Barker-Benfield , Bruce ( 1991), ‘Hogg-Shelley Papers of 1810–12’, Bodleian Library Record 14, pp. 14–29. Barker-Benfield , Bruce ( 1992 ), Shelley’s Guitar: An Exhibition of Manuscripts, First Editions and Relics to Mark the Bicentenary of the Birth of Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1792– 1992 (Oxford: Bodleian Library). Beatty, Bernard ( 1992 ), ‘Repetition’s Music: The Triumph of Life ’, in Everest ( 1992 a), pp. 99–114. Beavan , Arthur H . ( 1899 ), James and Horace Smith: A Family Narrative (London: Hurst and Blackett). Behrendt , Stephen C . ( 1989 ), Shelley and His Audiences (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press). Bennett , Betty T ., and Curran, Stuart (eds) ( 1996 ), Shelley: Poet and Legislator of the World (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press). Bennett , Betty T ., and Curran , Stuart (eds) ( 2000), Mary Shelley in Her Times (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press). Bieri, James (1990 ), ‘Shelley’s Older Brother’, Keats-Shelley Journal 39, pp. 29–33. Bindman , David , Hebron , Stephen , and O’Neill , Michael ( 2007 ), Dante Rediscovered: From Blake to Rodin (Grasmere: Wordsworth Trust).